Major-General Patrick Ronanye Cleburne: Cork’s Confederate General

By Ray Esten

By Ray Esten

Patrick Royanye Cleburne was one the most revered military leaders of the Confederate Army in the American Civil War. He started out as a private. Yet, within eighteen months he was a major general. All of which achieved without going through West Point and without any political connections.[1]

A man of extraordinary talents and a formidable character. It was said that he’ loved his friends and hated his enemies’ but, prays for their souls’.[2] His story is complex and contradictory, and it raises as many questions as it answers.

Background

Cleburne was an Irishman born at Desertmore, Cork on St. Patrick’s Day 1828. His parents were affiliated with the Anglican Church of Ireland. The son of a well-respected Dr. Cleburne, he entered Trinity College Dublin to study medicine.

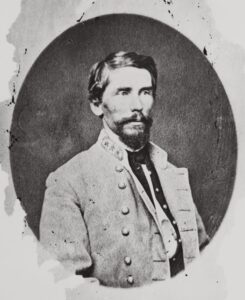

Cork-born Patrick Cleburne became a Confederate General during the American Civil War

Disgraced after failing an examination, he enlisted in the Forty-First Regiment of the British Army, as an ordinary soldier, in which reached only the rank of corporal before emigrating to America and settling with his brother and sister in Helena in the state of Arkansas. There, he studied law. Entered into a law partnership and established himself as a southern Democrat fiercely loyal to his adopted state.[3]

His arrival in America in 1849 coincided with at the height of the Irish exodus after the Great Famine. This mostly Catholic influx was viewed with disfavour by nativists who questioned their allegiance, lashing out at their work habits, politics, religion, culture and drinking practices.[4]

The Great Famine had impelled more than a million Irish to emigrate to the United States, most of them unskilled labourers who struggled for work and were plagued by poverty, hunger and disease.[5] The industrial cities of the North proved attractive to them and by 1860, one out of every six persons living in free (i.e. non-slavery) states was foreign born. By contrast, only one in thirty individuals living in the future Confederacy could claim a foreign birth.[6] The Irish contribution to the Civil War was predominantly to the Union. By the end of the war some 140,000 people of Irish birth had fought in the Union Army, as opposed to 30,000 who fought for the Confederacy.[7]

The Civil War

Decades of smouldering tensions over slavery, trade, tariffs, and states’ rights were brought to a head by the election of Abraham Lincoln in 1860. In response to Lincoln’s election, several southern states seceded and formed what became known as the Confederate States. The British government in whose Army Cleburne had served, declared neutrality, and forbade British subjects from enlisting on either side. Cleburne, however had American citizenship by this point.[8]

Decades of smouldering tensions over slavery, trade, tariffs, and states’ rights were brought to a head by the election of Abraham Lincoln in 1860. In response to Lincoln’s election, several southern states seceded and formed what became known as the Confederate States. The British government in whose Army Cleburne had served, declared neutrality, and forbade British subjects from enlisting on either side. Cleburne, however had American citizenship by this point.[8]

War Record:

Colonel: First regiment Arkansas infantry 1861

Brigadier General P.A.C.S., March 4 1862

Major General P.AC.S., Dec 13 1862

Killed at battle of Franklin Tennessee November 30, 1864 [12]

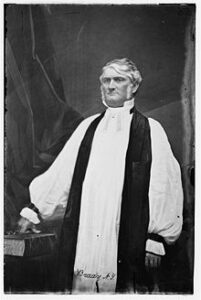

Tensions ran high in the southern states over joining with the Confederacy. For instance, it was reported that the residence of Bishop Polk and Elliot in Franklin county Tennessee were burned at midnight by the abolitionists, Mrs Polk being saved from the flames by a ‘trusty negro slave’. Both Tennessee and Cleburne’s adopted state of Arkansas declared for secession in 1861. The Arkansas state convention passed by a vote of 69 to 1.[9]

Arkansas was then a member of the Confederacy and Cleburne unhesitatingly supported its secession. With war clouds on the horizon he enlisted in a local militia company as a private but when the war broke out, he was elected captain.[10]

Many of the men that had served under Cleburne joined the 15th Arkansas Infantry of which he was made colonel. Cleburne had gained the status of a great fighting man, ‘’Old Pat’’ distinguished himself at the battles of Shiloh, at Richmond, Kentucky, at Perryville, at Murfreesboro. In March of 1862 he was commissioned a brigadier-general; in December 1862, he became a major general.[11]

Interpretations of the man

The first and perhaps the most trivial anomaly in the Cleburne narrative is his general appearance and accent. It was said of Cleburne that he was not handsome -a long and prominent nose and high cheekbones precluded.[13]

The first and perhaps the most trivial anomaly in the Cleburne narrative is his general appearance and accent. It was said of Cleburne that he was not handsome -a long and prominent nose and high cheekbones precluded.[13]

Contemporary writers have depicted him as striking looking if not handsome.[14] The reader can judge for themselves. However, it is generally agreed that he was over six feet tall. His shoulders bound and his eyes a grey shade of blue.[15]

The New York Herald maintained that Cleburne looked ‘as Irish as Sir Patrick Plenipo[16] however he talks without the accent of a Hibernian’.[17] The Public Ledger disagreed. They claimed that he could have been mistaken for a seaman and looked almost like a Greek. On his speech they said it was particular to himself, a cross between a stammer and an accent.[18] Interpretations were perhaps influenced by perceptions of the man. However, David T. Gleeson maintains that he had retained a strong Cork accent and anyone who met him knew he was an Irishman. [19]

Religion and political views

Being a member of the Episcopal Church, Cleburne was not of the religion of the majority of the Irish who had arrived in the 1840s. Generally, he was not known to get into discussions about his religion, but he remained a firm believer in the doctrines of his church.[20]

Politically his outlook was of a Whig and he had only joined the Democrats when the Whigs went over to the Know Nothing Party[21]who advocated the abolition of slavery as well as anti-Catholic-Irish and limiting immigration.

However, it seems that the issue of anti-immigration was what stirred Cleburne to make a speech in defence of his fellow countrymen. [22]

Slavery

There is no record of Cleburne speaking out against slavery but nor is there a record of him condoning it. It could be said that he was satisfied with the status quo. His grievance seems to have revolved around the right of a section of the country to govern itself.

Yet his silence on slavery contrasted with many Southerners, including, preachers who called out in defence of the ‘peculiar institution’ of slavery, referring to New Testament versus in its support and looking to divine providence to justify it.[23]

There is no record of Cleburne speaking out against slavery but nor is there a record of him condoning it.

There appeared to be a wide diversity of opinion between the Episcopal Church[24] of the North and South.[25] The latter, as a rule, believed that it belonged to them alone to deal with the perplexed problem of slavery, without interference from their Northern co-religionists. [26]

It could be argued that slavery was the glue that held the Confederacy together. It caused the economic prosperity of their region, and that knowledge created an economic bond among all classes of whites.[27] What was more, racially based arguments were calculated to rally non-slave holders to the defence of slavery,[28] deflecting from class tensions and uniting otherwise potential enemies.

President Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation in January of 1863, as the nation drew near its third year of civil war. The document declared that ‘’all persons held as slaves’’ in Confederate states were ‘’then, thenceforward, and forever free,’’

An article printed in the Times and reprinted in the Irish Times said …’’the soldiers of the North, full of ineradicable prejudices of blood and cast, will shrink from contact with the race which they regard as less than human.’’[29] The proclamation had, for the first-time, put slavery explicitly at the centre of the conflict.

In time, Northern soldiers became more amenable to Lincoln’s leadership and credited the proclamation as a way to weaken the South. Every slave who left a plantation, they reasoned, pulled a white Confederate out of combat to go back and work the land.[30]

Cleburne’s lost proposal

Cleburne was an eyewitness to the slump in recruiting and a downturn in Confederate morale. Perhaps, it spurred him to draft a proposal so controversial that President Davis had copies of the document destroyed. The only surviving document resurfaced in 1898-Major Calhoun Benham had requested it so he could prepare a rebuttal.[31]

In 1864, Cleburne proposed arming slaves and emancipating them and their families, to replenish Confederate troop strength and also to help win the propaganda battle abroad.

The most radical document written by a Confederate, it involved the arming and emancipating of slaves in return for their military service. Cleburne upheld that it would significantly supplement Confederate troops strength, alter foreign sympathies (slavery had kept England and France from recognising the Southern nation) and deprive the north of a reason to continue fighting. [32] ‘’I would meet the proclamation of Lincoln, he said, ‘with a better one. I would give the negroes not only their freedom, but a bounty of land for meritorious service.’’[33]

It would have wide implications that involved also the liberation of their wives and children, sanctified marriage, and given legal status to their paternity. He went so far as to suggest that it might to necessary to ‘’emancipate the whole race.’’[34] It is worth noting that Cleburne was not a slave holder.[35] But, more importantly he claimed to be backed by a number of generals. [36]

During the fall of 1864 however, the issue of arming the slaves suddenly went public, having assumed a critical urgency that stemmed from a series of devastating military and political reversals. [37]However, the idea received little support in the Confederacy to the last. Instead, blacks served Union blue with distinction, fighting in every theatre of war from the Rio Grande to Virginia.[38]

Fenian sympathiser or not?

A Northern General Thos. W. Sweeny (Cork born,) by flag of truce sent a message to Cleburne during hostilities. After the war was over, he said they would raise a Fenian army and liberate Ireland.

Two great generals of the American Civil War returning to Ireland at the head of a Fenian Army; the stuff of myth and legend. It was akin to the second coming of the Fianna warriors.

However, Cleburne’s answer to Sweeney was that after this war was closed he thought both would have had fighting enough to satisfy them for the rest of their lives.[39] In any case, Cleburne would not get the opportunity to become involved with a Fenian Army even if he had wanted to; he was killed in 1864.[40]

Cleburne was popular among Irish Americans in the south, but does not seem to have been an Irish nationalist.

Nevertheless, his heroic image was one that attracted Irish Americans. As his coffin passed through Memphis it was accompanied by the Emmet Guard (named after Robert Emmet 1778-1803). They had the honour of escorting the body to Helena Arkansas. After the war, one Fenian organiser noted that he could not get Irish southerners to name their circles after a Fenian prisoner in Ireland or Britain. However, the name of Cleburne had a ‘’talismanic’’ effect on them.[41]

But Cleburne might, in fact, have been hostile to Irish nationalism. As quoted in the Des Arch citizen of 1866 …’’he was opposed to any scheme of Irish independence. ‘’the Irish,’ he said, are not fit for liberty. They flourish better as exotics.’’[42] By exotics he perhaps meant that the Irish served better other counties and other empires than they did ruling themselves.

The battle of Franklin

‘’O my god this awful day!’’

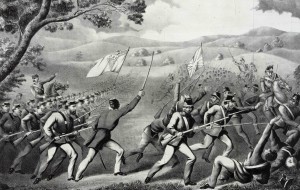

Cleburne took part in the Atlanta Campaign during the summer of 1864. On the fall of Atlanta, he accompanied the Army of Tennessee during the Franklin-Nashville Campaign. The Battle of Franklin was fought on November 30, 1864, in Franklin, Tennessee.

General John Bell Hood was in charge, the daring and dashing commander of the Confederates. He advised an assault on the Union troops well-fortified positions, even though he had no artillery support.

Patrick Cleburne was killed at the battle of Franklin in 1864

Cleburne, whose abilities on the battlefield were noted, advised Hood against sacrificing thousands of soldiers in such a senseless way.[43] But his advice was ignored, and Cleburne would also die that day; one of five general officers killed (Adams, Strahl, Granbury and Gist) and six wounded.[44]The great loss weakened the flexibility of Hood’s army and what is more important, did much to destroy its morale. General Chetham who visited the battlefield afterwards noted …’’the dead were piled up like shocks of wheat or scattered about like shifts of grain. [45]

Contested spaces

The body of Cleburne would not rest easy. On his burial at Columbia Cemetery it was discovered that those gallant men (Cleburne and other dead Confederates) were to be buried in the ‘potter’s field’ (or pauper’s grave) between a row of negroes and a row of federal soldiers. General Lucius Polk, the brother of General and Bishop Leonidas Polk offered a lot six miles south of Columbia.

The body of Cleburne would not rest easy. On his burial at Columbia Cemetery it was discovered that those gallant men (Cleburne and other dead Confederates) were to be buried in the ‘potter’s field’ (or pauper’s grave) between a row of negroes and a row of federal soldiers. General Lucius Polk, the brother of General and Bishop Leonidas Polk offered a lot six miles south of Columbia.

The body was moved to Ashwood Cemetery. In 1869 and at the request of a Nebraskan Ladies Confederate Memorial Association it was moved to the Confederate Burial Ground in Helena Arkansas.[46]

With a soldier’s pride for the South he died.

Southward he’s Bourne to southern earth

which he loved as if ‘twere the land of his birth[47]

Commemoration

Cleburne differed to men like General Tallaferro who owned a plantation in Arkansas of 1,800 acres and one hundred slaves.[48]

The Dundalk Democrat noted on his death- his intense Southerner feeling and that he considered the South much oppressed by the North … ‘’though strange to say his opinions were anti-slavery.’’ Also, that his brother (and family) ‘remained true to the flag which he had so ungratefully forsaken’.[49] The Brooklyn Eagle praised Cleburne who had ‘secured by his humanity to hundreds of our prisoners the respect from our side which his bravery obtained him from his own’.[50].

The final resting place of Cleburne’s in Arkansas became a shrine to Confederate enthusiasts. His memory would be cast in bronze, chiselled in stone. His name was remembered in Tennessee, Texas, Alabama and his adopted Arkansas. Yet, at times it was a contested memory. Not least in his home county.

Alfred Allen of Ovens Cork in a reply to Padraig O Maiden newspaper article, the Irish Examiner dated 1970 noted that he was in possession of letters sent home by Cleburne. In them he claimed that Cleburne expressed enthusiasm for the egalitarians and democratic atmosphere  which he found in America. Allen added that makes it all the more remarkable that he died defending slavery. He also addressed the claim that Cleburne was a Fenian.

which he found in America. Allen added that makes it all the more remarkable that he died defending slavery. He also addressed the claim that Cleburne was a Fenian.

He remarked if he was …’’which I doubt, he was dead before Fenianism got into its stride, he was in good company as (John) Mitchell[51] was an ardent advocate of slavery.’’[52] Undoubtably, Cleburne story has a number of narratives and interpretations.

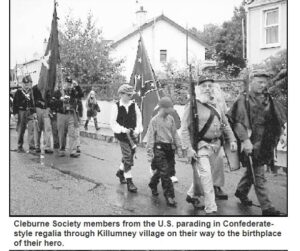

During the late twentieth century Cleburne’s home in Cork became a place of pilgrimage for battlefield enthusiasts, such as Mr. John P. McAnaw, a retired colonel with the U.S. Army. He paid tribute to General Cleburne whom he saw as a real soldier who had a great rapport with his men. “He had everything I would look for in a commander — he was genuinely concerned with his men and won their love and respect,” The visitors who accompanied McAnew were mostly battlefield re-enactors. They dressed in Confederate and Union uniforms and marked their visit by firing three volleys of shots in the grounds of the house.[53]

In 1999 it was proposed to name the new Ballincollig bypass in Cork after Patrick Cleburne.

It was during this period that some kind of memorial to Cleburne was suggested. However, the question was not debated with any seriousness until the millennium when Cork County Council’s Brandon-Macroom Area Committee debated if the Ballincollig bypass should be named after …’’American Civil War Hero who hailed from nearby Bridge Park Cottage, Kilumney’’. The Ovens Cleburne Society which had been formed in 1999[54] pointed to the tourist potential of the project and that the Cleburne house had been maintained in its original condition.

Early in the debate it was stated that Cleburne never owned a slave. He was, in fact, opposed to slavery. [55] This was a significant factor in defence of not only his reputation but the renaming as well. The debate was protracted and at times heated. It carried on for some months. Mr. Donal Moynihan TD wanted instead it named for a person who had fought for Irish freedom. The chairman Mr. Kevin Murphy said that no one was turning their back on anybody nor was any Irish patriot being devalued by the naming of an Irish born American hero.

Senator Peter Callahan seconded Moynihan stressing that he had no problem with it being named after Cleburne, the question to be asked was whether there was a shying away from honouring the memory of Irish patriots because it might not be deemed politically correct.[56]

This was the stance taken during that period. It would be a very different debate today. Members of the Cleburne family arrived in 2001 (for the first time); the trip being organised by the Cleburne Society of Georgia. RTE Nationwide had a camera crew on site.

Also, there was Muriel Joyslyn who has written extensively on the Confederate army and done a biography of Cleburne. Members of the Franklin Cleburne Society turned out complete with Confederate flags and fired a twenty-one-gun salute. The husband of Joslyn informed the local Cork newspaper, the Southern Star that a statue was to be erected to Cleburne in Georgia.[57] The statue would prove to be controversial in the years ahead.

Historical Wounds

Historical wounds don’t heal quickly. We know this through the annals of our island. Yet, nowhere is this more evident today than in the United States of America. Yes, Slaves gained their emancipation over a hundred and fifty years ago. Yet despite its dissolution, slavery has shaped social, economic, and political agendas since its inception in the United States.

There are no ethical or honest values that could justify the practice. Only those who wish to distort the truth could claim it. The Confederate flag is considered to be a slap in the face to people of African descent. A controversy that played out in Cork in 2017, with G.A.A Supporters, who had for many years flown the flag in the rebel county-similar colours to Cork’s flag. It was justly viewed in 2020 to be insensitive and the G.A.A came down firmly on it.

However, across the Atlantic the atmosphere is more charged. The Cleburne monument in Georgia became part of a larger debate in 2019, in which the state of Georgia called for the protection of all monuments. An invigorated black movement spearheaded by the Black Lives Matters campaign called for the dissolution of such.

Cleburne did not own slaves and even advocated a form of emancipation. But he still fought in the cause of slavery for the Confederacy.

Where does Cleburne stand?

No individual is one dimensional and not one narrative can explain everything about them. Yet Patrick Cleburne makes for a peculiar Confederate. Anne J. Bailey in her study of ethnicity in the Civil War stated that …’’ noble as Cleburne’s proposal might sound to us today, it was extremely naïve for the time.’’ The Confederates would have never tolerated armed blacks in their own ranks.[59] Nevertheless, once Cleburne put on that grey uniform, he became a protector of the Confederacy. In effect he took on the role of defender of slavery. This is a strong argument.

The bypass at Cork is a long-gone issue. A modern debate around Major General Cleburne would be very different. No longer consisting of questions like, is it not better to name a bypass for someone who died for Irish Freedom, instead of some Irishman who fought for a foreign country.

There are other narratives and other ways of looking at it. Some of them might prove confrontational. Inevitably, we don’t all share the same viewpoint. However, any refusal to talk about such topics is fallacy. Worse still, it is history denied.

References

[1]Manitowoc Pilot, August 28, 1863.

[2] Cleveland Morning Leader November 10, 1864.

[3] Paul R. Fessler The Case of the Missing Promotion: Historians and the military career of Major General Patrick Royayne Cleburne, C.S.A. The Arkansas historical Quarterly Vol. 53, No. 2, Summer 1994 p. 123.

[4] Kevin Kenny Lincoln and the American Irish American Journal of Irish Studies 10 (2013) P. 45.

[5] Peter Gottschalk American Heretics Catholics, Jews, Muslims and the History of Religious Intolerance (New York 2013) pp. 37-8

[6] Anne J. Bailey Invisible Southerners: Ethnicity in the Civil War (Georgia 2006) p. 1.

[7] Kevin Kenny Lincoln and the American Irish American Journal of Irish Studies 10 (2013) P. 49.

[8] E. L Woodford The Age of Reform 1815-1870 (Oxford 1939) pp. 265-6

[9] Irish Times May 21 1861

[10] Victor Searcher. An Arkansas Druggist Defeats a Famous General

The Arkansas Historical Quarterly

Vol. 13, No. 3 (Autumn, 1954) p. 255.

[11] Ethel Linder The Arkansas Historical Quarterly, Winter, 1945, Vol. 4, No. 4 (Winter, 1945) p. 133.

[12] Military Record of General Officers of the Confederate State of America. Commander in Chief, Generals, Lieutenants Generals and Majors compiled by Charles B. Hall. p. 55.

[13] The New York Herald October 29. 1864.

[14] Ethel Linder The Arkansas Historical Quarterly, Winter, 1945, Vol. 4, No. 4 (Winter, 1945) p. 312

[15] Charles L. Dufour Nine Men in Gray ((New York 1963) P. 76

[16] Sir Patrick Plenipo was a popular play at the time.

[17] The New York Herald October 29. 1864.

[18] Public Ledger July 17. 1866

[19] David T. Gleeson Another “Lost Cause”: The Irish in the South Remember the Confederacy

Southern Cultures Vol. 17, No. 1, The Irish (Spring 2011), p 10.

[20] Biographical Sketches of Gen. Pat Cleburne and Gen. T. C. Hindman. Together with Humorous Anecdotes and reminiscences of the late civil war By Charles Edward Nash, M. D., Little Rock, Ark. 1898 p. 34

[21] Barbara C. Ruby General Patrick Cleburne’s Proposal to Arm Southern Slaves

The Arkansas Historical Quarterly

Vol. 30, No. 3 (Autumn, 1971) p. 194.

[22] Craig L. Symonds Stonewall of the West. Patrick Cleburne and the Civil War (Kansas 1997) p. 38.

[23] Ted Booth Trapped by His Hermeneutic: An Apocalyptic Defence of Slavery Anglican and Episcopal History Vol. 87, No. 2 (June 2018) p. 165.

[24] The Protestant Episcopal Church in the Confederate States of America was an Anglican Christian denomination which existed from 1861 to 1865.

[25] Robert L. Crewdson Bishop Polk and the Crisis in the Church: Separation or Unity?

Historical Magazine of the Protestant Episcopal Church

Vol. 52, No. 1 (March, 1983), pp. 20-47.

[26] Edgar Legare Pennington The Organization of the Protestant Episcopal Church in the Confederate States of America Historical Magazine of the Protestant Episcopal Church

Vol. 17, No. 4, The Church in the Confederate States (DECEMBER, 1948), p.1.

[27] James L. Huston Property Rights in Slavery and the Coming of the Civil War The journal of Southern History vol. 65, No. 2 (May, 1999) P 263.

[28] James L. Huston Property Rights in Slavery and the Coming of the Civil War The journal of Southern History vol. 65, No. 2 (May, 1999) P. 255.

[29] Irish Times 19. June 1863.

[30] Woden Teachout Capture the Flag A Political History of American Patriotism (Philadelphia 2009) pp. 100-2.

[31] Anne J. Bailey Invisible Southerners: Ethnicity in the Civil War (Georgia 2006) p. 50.

[32] Paul R. Fessler The Case of the Missing Promotion: Historians and the military career of Major General Patrick Royayne Cleburne, C.S.A. The Arkansas historical Quarterly Vol. 53, No. 2, Summer 1994 P. 124.

[33] Des Arch Citizen July 28, 1866.

[34] Anne J. Bailey Invisible Southerners: Ethnicity in the Civil War (Georgia 2006) p. 49.

[35] Charles L. Dufour Nine Men in Gray ((New York 1963) P. 77.

[36] Barbara C. Ruby General Patrick Cleburne’s Proposal to Arm Southern Slaves. The Arkansas Historical Quarterly Vol. 30, No. 3 (Autumn, 1971) p. 204.

[37] Mark L. Bradley”This Monstrous Proposition”: North Carolina and the Confederate Debate on Arming the Slaves. The North Carolina Historical Review, p. 153

[38] Anne J. Bailey Invisible Southerners: Ethnicity in the Civil War (Georgia 2006) pp 66-67.

[39]Dual Allegiances: A Fenian Message during the Atlanta Campaign, 1864’ https://irishamericancivilwar.com/2011/04/02/dual-allegiances-a-fenian-message-during-the-atlanta-campaign-1864/

[40] Dual Allegiances: A Fenian Message during the Atlanta Campaign, 1864’ https://irishamericancivilwar.com/2011/04/02/dual-allegiances-a-fenian-message-during-the-atlanta-campaign-1864

[41] David T. Gleeson Smaller Differences: “Scotch Irish” and “Real Irish” in the Nineteenth-Century American South New Hibernia Review / Iris Éireannach Nua

Vol. 10, No. 2 (Summer, 2006), pp. 68-91.

[42] Des Arch citizen July 28, 1866.

[43] Paul R. Fessler The Case of the Missing Promotion: Historians and the Military Career of Major General Patrick Ronayne Cleburne, C. S. A. he Arkansas Historical Quarterly

Vol. 53, No. 2 (Summer, 1994), pp. 211-222

[44] Thomas Robson Hay Hood’s Campaign (New York 1929) p. 130.

[45] W. W. Gist THE BATTLE OF FRANKLIN Tennessee Historical Magazine

Vol. 6, No. 4 (JANUARY 1921), pp. 220-233

[46] A Memorial and Biographical History of Johnson and Hill Counties, Texas (Chicago 1892) p. 142.

[47] Memphis Daily April 18. 1870.

[48] Irish Times May 22. 1863.

[49] Dundalk Democrat 07.01. 1865.

[50] The Brooklyn Daily Eagle 17. December 1864.

[51]John Mitchell was an advocate of the slave trade. Two of his sons died for the South and another lost an arm.

[52] The Irish Examiner Friday March 26 1970.

[53] Southern Star Saturday, April 11, 1992.

[54] Southern Star 05. 8 1999.

[55] Southern Star 29.04 2000.

[56] Southern Star 12.08. 2000.

[57] Southern Star July 17 2001.

[59] Anne J. Bailey Invisible Southerners: Ethnicity in the Civil War (Georgia 2006) p. 55.