Lord George Hill, Improving landlord or cruel ‘Lord of the Soil’?

The modernising Irish Landlord who married not one but two nieces of Jane Austen. By John Joe McGinley

Lord George Augusta Hill the 3rd was an Irish military officer, politician, landlord and author.

He would go on to marry not one but two nieces of Jane Austen and become somewhat of a poster boy for Victorian Anglo-Irish landlordism in Ireland, following the publication of his book ‘Facts from Gweedore’ in 1845.

This was his account of the conditions of his tenants in Gweedore and the defence of the agricultural and structural reforms that he implemented in his estates from 1838 onwards. While many other Landlords strived to copy Hills draconian reforms, the House of Commons select committee on Irish Poverty was less enthusiastic and even went as far to investigate his methods.

Lord George Hill was a flamboyant and complex character, and this is his story.

Early Life

George Hill was born on the 9th of December 1801, the 7th and last child of Arthur Hill the 2nd Marquis of Downshire and Mary Baroness Sandys. Arthur Hill while Governor of Down and a member of the Privy Council of Ireland vigorously opposed the union of the UK and Irish parliaments.

His reward was to be removed as Governor and stripped of his place on the Privy Council. Humiliated, he committed suicide in September 1801 just 3 months before the birth of his Son.

George was always a favourite of his mother and with no prospect of inheriting his late father’s titles, his options of advancement lay in either a good marriage or a military career.

George Hill came from an aristocratic background in County Down and served as an officer in the Royal Horse Guards.

Aged just 16, he joined the Army as a Cornet in the Royal Horse Guards. This was the third and lowest grade of commissioned officer in a British cavalry troop, after captain and lieutenant. It is equivalent to a modern day second lieutenant. He was promoted to lieutenant in 1820. Five years later he was transferred to the Royal Irish Dragoons as Captain. He served throughout the north of Ireland on what were termed ‘peace keeping’ duties.

In April 1830 at the relatively young age of 29, he was made ‘Aide de camp’ to Sir John Byng, the commander in chief of the crown forces in Ireland, with the rank of Major. In June of that year, he joined what was coined the half pay list. This was the pay or allowance an officer received when in retirement or not in actual service. (1)

Member of Parliament

He did so out of family duty, he was required by his brother the 3rd Marquis of Downshire to stand in the election which was triggered by the death of King George IV.

George Hill was proposed for the seat of Carrickfergus and after a hard fought and dirty electoral battle, he was duly elected as a supporter of the Duke of Wellington’s conservative faction in the new parliament of September 1830.

Hill served as a conservative MP for Carrigfergus between 1830 and 1832.

Despite being recognised as a supporter of Wellington, Hill was his own man and he failed to attend the vote of confidence in Wellington’s administration on the 15th of November 1830, His absence helped bring the Dukes term as prime minister to an end. George never uttered one speech in his parliamentary career, which came to an end in 1832, when he resigned claiming ill health. (2)

He returned to Ireland to help his brother Lord Marcus Hill be elected the MP for Newry. (3)

His health seemingly restored in 1833, George Hill was soon appointed the largely symbolic role of comptroller in the household of the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland. The following year on the 21st of October 1834, Lord George Hill married Cassandra Jane Night the daughter of Edward Austen Knight, the brother of the novelist Jane Austen. They would go on to have four children.

Landlord in Gweedore

In March 1838 he sold his commission in the 47th regiment of foot and using funds provided by his late mother’s will and other family members, he purchased land in Gweedore, county Donegal. He would go on to expand his holdings to 23,000 acres including a number of offshore islands, the largest of which was Gola island.

The area lacked real infrastructure with its roads in a deplorable state. In 1837 the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland on his tour of Ireland appalled by the state of the roads was barely able to travel through Gweedore.

In 1838, Hill sold his army commission and used the money to buy an estate in west Donegal.

During his journey he was petitioned by the local School master Peter McKye Who pleaded for assistance saying that:

“That the parishioners of this parish of Tullaghobegly, in the Barony of Kilmacrennan, are in the most, needy, hungry, and naked condition of any people that ever came within the precincts of my knowledge, although I have travelled a part of nine counties in Ireland, also a part of England and Scotland, together with a part of British America. I have likewise perambulated 2,253 miles through some of the United States, and never witnessed the tenth part of such hunger, hardships, and nakedness”. (4)

It was into this seemingly backward and impoverished parish that Lord George Hill came as a landlord and unlike others before him he was determined to stay and change Gweedore forever. Hill also had an advantage that many other Anglo-Irish landlords did not have. He knew and spoke Gaelic, the main language of the people of Gweedore.

His first impressions of Gweedore were not favorable. In his book Facts on Gweedore written in 1845 he described Gweedore as:

“Ruled by a few bullies, and lawless distillers, who acknowledged neither landlord or agent; and the absence of anything like roads effectively kept civilization from the district, and prevented people bringing more land into cultivation.” (5)

Abolishing the ‘Rundale sytem’

His first task was to change the inhabitant’s perception of paying rents and taxes, which was reluctant and sporadic at best. In 1834 it was recorded that two revenue police parties “were “beaten and disarmed” and “fifty constabulary were repulsed and forced to give up collecting the tithe. (6)

He believed that the best way to modernise Gweedore, would be to end the Rundale system and ensure the payment of rents and other payments.

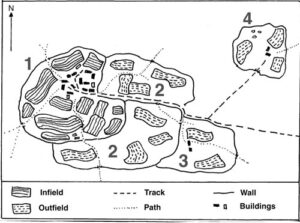

The Rundale system of land holding was prevalent in the western part of Ireland before the famine. In this system, the land was leased to one or two tenants, who then divvied it up amongst 20-30 others (in many cases the whole town). The land was held in joint tenancy (a partnership of tenants).

Hill abolished the ‘Rundale’ system, by which tenants held a tenancy in common, replacing it with individual plots.

Under this system the land was divided into several areas based on varying land quality. An “infield area” that was composed of land to grow crops and an “outfield” area further out that was used for grazing usually radiated out from the homes. (7)

This was an ancient form of land division that, despite its faults, allowed everyone access to the best land, water and common grazing. It also allowed subdivision of lots to accommodate the need for sons to have their own farms.

Lord George Hill believed the Rundale system was a barrier to his plans to introduce more modern and profitable farming methods and his desire to bring sheep into Gweedore. He would later describe the system in ‘Facts from Gweedore’ as:

“The cause of “fights, trespasses, confusion, disputes and assaults”. (8)

Building infrastructure

Lord Hill also began improving the transport infrastructure in Gweedore. The first road was built in 1834 by the Board of Works from Dunlewey to the Gweedore River. A series of roads were then built throughout the Gweedore estate.

Hill built a harbor, a grain store and created a general store which sold a wide variety of merchandise. He even set up a bakery importing a Scottish baker by the name of Mason. The creation of the grain store was no philanthropic exercise it had a twofold objective. The first was to control the supply and price of grain and ensure that his tenants would not only grow the crop but once they sold it they would have capital to then pay his rents.

Secondly by controlling the grain supply he hoped to discourage the distillation of grain alcohol and end what he perceived to be a scourge of drunkenness throughout his estate. In later years Hill would admit he was not successful in this endeavor! Lord Hill’s long-term plan was to introduce large scale sheep farming in Gweedore and in preparation for this he contracted the London firm of Allen and Solly who set up an agency in the area.

They would supply wool (which would eventually come from Hills sheep) and purchase knitted products. The local population had always made their own clothing and knitted garments from the small-scale sheep farming in the area. This initiative was extremely popular and was estimated to inject £500 per annum into the local economy.

In a bid to encourage tourism in the area, Lord George Hill constructed a hotel, which was designed to emulate the highland lodges of Scotland, designed for visitors to enjoy fishing and hunting in the local area.

He also created what was known as a model farm beside the hotel to showcase the modern techniques he wished his tenants to adopt.

Survey

In his push to end the Rundale system, Hill began an exercise to survey his estate between 1841 and 1843. He used the results to allocate new holdings to each tenant.

Hill even went so far as to outlaw the building of any new houses and the further subdivision of land or the sale of tenants’ rights.

The prohibition on any further land subdivision was a particularly draconian act as it meant that no family could provide land for their sons or daughters. This meant that emigration was usually the only option for them.

In another attempt to improve the land on his estate, Hill offered prizes to his tenants for best kept cottage, best vegetables and healthiest livestock. It was initially rebuffed by his tenants but over time they began to participate enthusiastically.

Lord Hill did however, bar anyone from entering who was found to be producing poteen, who had been convicted of breach of the peace or who was behind with their rent.

Personal tragedy and second marriage

In March of 1842 tragedy struck when Hills wife Cassandra Jane died 2 days after the birth of their 4th child. Cassandra Jane Louisa. Cassandra’s sister Louisa Knight, Jane Austin’s god-daughter moved to Ireland to look after Hill’s children.

Women often died in childbirth, and their unmarried sisters, who had few other options to support themselves besides marriage, would step in to care for the family. For convenience, and sometimes developing love, remarriage seemed like the thing to do.

George and Louisa would eventually marry on the 11th of May 1847.

In 1842, Hill’s wife Cassandra died in childbirth. He later married her sister Louisa.

The marriage was controversial and even prompted an investigation in the UK parliament looking at the legality of a marriage between a widower and his deceased wife’s sister. The issue was:

“whether a man’s wife’s sister was, in law, the equivalent of his blood sister and therefore never to be his wife, or his metaphorical sister only and therefore an ‘indifferent person’ whom he could marry” (9)

The marriage was ultimately not contested, and they would go on to have a happy marriage and one son, George.

‘Facts on Gweedore’

In 1845 as was common for many Landlords, Lord George Hill was appointed the High Sheriff of Donegal which was the British Crown’s judicial representative in County Donegal from the late 16th century until 1922, when the office was abolished in the new Irish Free State and replaced by the office of Donegal County Sheriff. The High Sheriff had judicial, electoral, ceremonial and administrative functions and executed High Court Writs.

Also, in 1845, as Famine began to stalk the Irish landscape Lord George Hill published his book ‘Facts From Gweedore’. It would eventually run to five editions and played a major role in the often-bitter public debates about the effects of Irish landlordism in post-famine Ireland.

Professor Evans of the Institute of Irish Studies of Queens University, Belfast describes the booklet as: “The most detailed account we have of the rural world of the Gael, of its cultural and physical attributes in the days before the great famine,” (10)

In 1845, Hill published ‘facts on Gweedore’ which variously seen as a valuable source on pre-famine life and as an unwarranted attack on the people of west Donegal by a cruel and unjust landlord.

And in Hill himself he saw: “an outstanding and in many ways an exceptional figure among Irish landlords of the nineteenth century.” (11)

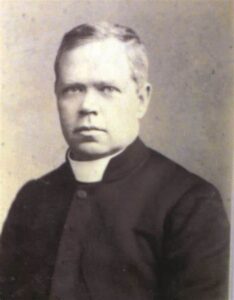

Father James McFadden the parish priest of nearby Falcarragh and a land league campaigner who would become the parish priest of Gweedore in 1875, had a rather more cynical view of the book. He called it:

“This is a summary of the alleged facts from Gweedore, which might, perhaps, with more regard to truth and accuracy be called “Fictions from Gweedore”, conceived, arranged, and printed by the Lord of the Soil himself, to dispose public opinion, to receive with equanimity the shock and outrage imparted to it by the cruel, not to say, unjust action of doubling the rents, appropriating immemorial rights, and otherwise oppressing an already rack rented and harassed tenantry.” (12)

Perhaps Father McFadden who was a constant thorn in Hills side in his later life had an ulterior motive to denigrate Facts from Gweedore. As a member of the Land League and a campaigner for tenants’ rights and no friend of landlords, McFadden was determined to highlight the negative impact of Hill.

Readers should indeed be sceptical and understand why ‘Facts for Gweedore’ was written, before looking at its historical accuracy.

It was Lord George Hill’s intention to achieve two objectives with the publication his book. The first was purely financial to encourage tourism and visitors to his newly build hotel.

The second was more personal, to paint Hill in a positive light. He wanted to show that the improvements he had made in farming methods, manufacturing and infrastructure had improved the lives of his tenants. He wished to be recognised as a benevolent landlord in an era of land wars, famine and the turmoil of eviction.

No matter how well Lord Hill wished to portray his agricultural changes, the majority of his tenants were subsistence farmer’s dependant on grain and livestock to pay their rent and potatoes to live. They were one bad harvest away from famine.

Famine

Potato blight was not new to Ireland and partial crop failures were recorded in 1831, 1837, 1854 and 1856. A complete failure of the potato crop in 1845 heralded ‘An Gorta Mór’ the great Irish famine of 1845 to 1849. The great hunger was a period of mass starvation, disease but above all state negligence. Gweedore did not escape the horrors of the famine.

Barry D Hewitson, writing, from Gweedore, to the Belfast Ladies Association for the Relief of Destitution in 1847 said:

The people of the Gweedore area suffered terribly in the famine, but, in stark contrast to other areas othe Atlantic coast, the population there actually rose during the famine years.

“I have just returned after a day of painful exertion…in one house I found a family of fourteen – the eldest fourteen years of age, the youngest nine weeks – the mother unable to leave her bed since its birth. They had not a morsel of food in the house… I went to another house to inquire about a young woman who had been employed on the public works and had gone away ill during the severe snowstorm. On reaching home she complained of great coldness; her mother and father made her go to bed (the only one in the house); she fell into a sleep from which she never woke. This day her poor mother died also, and there are two of the children who, I am sure, will not be alive by tomorrow, to such a state are they reduced from bad and insufficient food. Lord George Hill is doing all that a man can do. He is occupied from morning till night sparing himself neither trouble nor personal fatigue.” (13)

Lord Hill’s attitude to the famine was harsh and some would say even cruel but not uncommon among the Anglo-Irish aristocracy He wrote:

“The Irish people have profited much by the Famine, the lesson was severe; but so were they rooted in old prejudices and old ways, that no teacher could have induced them to make the changes which this Visitation of Divine Providence has brought about, both in their habits of life and in their mode of agriculture.” (14)

Despite this, it must be said that Lord Hill unlike many of his contemporary’s did at least try to help his tenants. He appealed for funds to alleviate the hardship to organizations such as the society of Friends (the Quakers), the Irish Peasantry Improvement Society of London and the Baptist Society for funds.

One government tactic during the famine, which led to so much hardship and death was to protect the price of grain and only sell at the prevailing market prices. Lord George Hill again unlike so many landlords decided to sell grain to his tenants at a loss. The Corn Mill in Bunbeg proved a fortuitous enterprise and ground 688 tons of Indian corn to mitigate the hardship of the famine.

However, some were not impressed, and later Father McFadden was again harsh in his criticism:

“He [Hill] got over £700 from Government for grinding Indian corn in 1847!! The meagre outdoor relief he gave to some tenants of a stone of meal in the week or fortnight, was to keep them out of the workhouse.” (15)

During the famine Ireland’s population fell by between 20% and 25%. However, perhaps due to the fruits of the wild Atlantic, especially edible seaweed and the actions of Lord George Hill, the population of Gweedore, whilst suffering hardship actually rose.

‘The most deplorable destitution’

In February 1858 Hills tenure in Gweedore was attacked in the press where an appeal by ten catholic priests including Daniel McGee, P.P. Gweedore and James McFadden C.C. Cloughaneely was published:

“In the wilds of Donegal, down in the bogs and glens of Gweedore and Cloughaneely, thousands and thousands of human beings, made after the image and likeness of God, are perishing, or next to perishing, amid squalidness and misery, for want of food and clothing, far away from aid and pity. On behalf of these famishing victims of oppression and persecution, we appeal for substantial assistance to enable us to relieve their wretchedness and rescue them from death and starvation.

There are at the moment 800 families subsisting on seaweed, crabs, cockles, or any other edible matter they can pick up along the seashore or scrape off the rocks. There are about 600 adults of both sexes, who through sheer poverty are now going barefoot, amid the inclemency of the season, on this bleak northern coast. There are about 700 families that have neither bed nor bedclothes… Thousands of the male population have only one cotton shirt; while thousands have not even one. There are about 600 families who have neither cow, sheep, nor goat and who…hardly know the taste of milk or butter. This fine old Celtic race is about being crushed to make room for Scotch and English sheep.” (16)

A relief committee was established and this stark imagery prompted a parliamentary select committee to be established in June 1858 to investigate the claims of extreme poverty in Gweedore.

In 1858, a commission of inquiry noted extreme poverty and destitution in the Gweedore area. Hill denied it.

The committee heard evidence from a wide variety of witnesses. On one side were the Landlord Lord Hill and members of the local gentry including visitors to Hill’s hotel that claimed that no such poverty existed. On the other, were the clergy and tenants who maintained that destitution was rife and poverty endemic.

One witness a reporter from the Dublin Evening post, James Williams, testified that what he saw in Gweedore was:

“The most deplorably degraded state of destitution that I ever saw.” (17)

He went on to say that it was his impression that: “It was the determination of Lord George Hill to exterminate the entire race.” (18)

A more balanced view came from local priest Fr Doherty who gave Lord George Hill credit for building roads, a shop, a post office and a quay at Bunbeg. He also went as far to say Hill had saved many from dying during the famine. His grievance was that poverty was being created by the removal of the mountain grazing, which was a real harm to his people’s livelihoods.

Lord George Hill gave his evidence to the committee on the 23rd and 24th of June.

It came as no surprise that the select committee found in the Landlord’s favour and declared that there was no evidence of destitution, saying:

-“….it appears to Your [Queen Victoria’s] committee that destitution, such as complained of in the Appeal of 8 January 1858, did not and does not exist….” The statements of the appeal “are not borne out by the evidence taken before them; and Your committee have come to the conclusion that those representations are calculated to convey to the public a false and erroneous impression of the state of the people in this district As to the claim that the Landlords took away the mountain grazing, a claim crucial to the priests case, the Committee decided to be “totally devoid of foundation.” (19)

This not unexpected decision did not deter the relief committee who went on to raise £2,196 5s 7d. Up to the time of the Select Committee hearing they had given out £1,600 worth of clothing, seed and money.

Later life and death

Lord Hill continued with his drive to modernise Gweedore but was increasingly worn down by the rising opposition to his plans. With the arrival of Father McFadden in Gweedore in 1875, Hills troubles increased, it was the bailiff’s opinion that the people of Gweedore were under the “complete authority” of Fr McFadden.

In ill health Hill retreated more and more to his home Ballyare House in Ramelton, where he died on the 6th April 1879 (aged 77). He was buried at Conwal Parish Church in Letterkenny, alongside Cassandra Jane Knight the first Austen to whom he was married.

So ended the life of the man who was elected to parliament but never made a speech , an MP who helped bring down Wellingtons Government, the landlord who could speak Irish and the man who married not one but two nieces of Jane Austen.

Sources

- Belfast Newsletter, 16 Apr. 1830.

- History of Parliament

- Newry Commercial Telegraph, 4 Jan. 1833.

- Memorial of Paddy McKye, Gweedore, 1837 (donegalgenealogy.com)

- Facts from Gweedore Lord George Hill 1845

- Facts from Gweedore Lord George Hill 1845

- Irish Geography website

- Facts from Gweedore Lord George Hill 1845

- Anne D. Wallace, “On the Deceased Wife’s Sister Controversy, 1835-1907

- His life and fortune to civilise Gweedore: RTE Documentary on 4th May

- His life and fortune to civilise Gweedore: RTE Documentary on 4th May

- JJ McFadden The past and present

- The Famine in Ulster: The Regional Impact, Ulster Historical Foundation, Belfast, 1997

- Introductory chapter to the third edition of Hill, Facts from Gweedore (1853)

- JJ McFadden The past and present

- Freeman’s Journal 12th Feb 1858

- Parliamentary Report 1858 questions 1234-1251

- Parliamentary Report 1858 questions 1234-1251

- Parliamentary Report 1858 Gweedore p91