The Cattle Drives of 1920: Agrarian Mobilisation in the Irish Revolution

By Terry Dunne

In 1925 Clare was bedecked with posters bearing what we might think of as a fiery revolutionary message. They read:

‘There is a prairie of untenanted land in Clare; there are poor men in uneconomic holdings; there are bogs unevenly distributed; ranches in the hands of the very few. These must be partitioned and divided into lots, to make what was uneconomic economic.’[1]

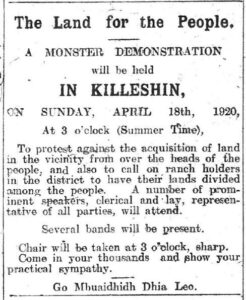

Those were posters of the ostensibly conservative Cumann na nGaedhael party, something which is testament to the continuing widespread popularity of the cause of ‘The Land for the People’.

This was the outcome of a wave of rural protest. In 1920, Ireland, particularly its rural west, was rocked by mobilisation for ‘The Land’ alongside the mobilisation for ‘The Republic’. This article explores how the land question and its settlement helped to shape independent Ireland.

The economic basis of agrarianism

To understand agrarian mobilisation in the revolutionary period it is necessary to understand that the bulk of higher value farmland was located on large farms, that is, farms of over 100 acres. [2]

Meanwhile the majority of farms were regarded as ‘uneconomic’ by the relevant government departments of both the British state and the post-1922 Irish Free State. Or in other words those farms were too small in area and they were located in places with strong environmental constraints, such as heavy rainfall and harder to work soils.[3]

This in a context where in most of Ireland the sole industry was agriculture, and where the predominant branch of agriculture, raising beef cattle, offered comparatively little waged employment. For this reason, and because there was a well-established tradition of collective action, agrarian insurgency continued long after the comparatively well-known Land War and Plan of Campaign era of the late-nineteenth century. More relevant to the 1917-23 period was the sharply unequal distribution of farmland.

The majority of farms in early 20th century Ireland were regarded as ‘uneconomic’ or too small or too poor in soil to make a living from.

But there were still tenant farmers in the years of the revolution as many tenants had yet to buy out their farms under the Land Acts.[4]

The Great War and its aftermath intensified the land problem. Firstly, migration was curtailed, so more young people were left in Ireland. Migration was an integral part of the agrarian economy, migrant labour was as much part of its output as beef was. Secondly, the state programme of land re-distribution was put on hold for the duration of the conflict – the money which would have gone on it was now being spent on the war effort.

Since 1891 the British state had embarked on a comparatively limited programme of land re-distribution. This was carried out through a state agency called the Congested Districts Board and was confined to the counties of the western seaboard.

Most of these years were a boomtime for agriculture.[5] That had the likely consequence of making the prospect of the possession of land, or more land, more alluring, while at the same rising land values put it more and more out of reach. These were basic issues of livelihood, not a romantic attachment to land, in fact twentieth-century Ireland was characterised by a flight from the land. Indeed, arguably what was at the heart of the whole issue was a lack of local industrial development which could offer sources of livelihood other than farming.

The context changed somewhat in 1922 with the onset of a depression in the demand for Irish agricultural outputs, with the reopening of worldwide markets to producers such as Canada, New Zealand and Denmark. The result was another round of land agitation in 1922‒23, which included more of an emphasis on rent. In December 1922, The Free State’s Minister for Agriculture Patrick Hogan, whose visit to Clare was announced by the aforementioned posters, claimed:

‘For the last couple of years, there has been practically a general strike by tenants against the payment of rents to landlords. Generally speaking the cause alleged was the inability to pay due to the depression in agriculture. Possibly the desire to force land purchase has given its chief strength to this no rent movement.’[6]

Agrarian social conflict in years 1917‒23 involved struggles between landlords and tenants, struggles between different strata of farmers, and struggles between farm workers and their employers. Across the decades from the 1760s onwards this more diverse pattern was actually as typical, or even more typical, than the perhaps fleeting moments where a unified tenant community faced down the landlord class. [7]

‘Clear the cattle off every ranch’

For decades land issues were of great importance to Irish nationalist politics. Nationalism became popular in rural Ireland principally through an orientation to the interests of agrarian classes. Indeed, Sinn Féin and the Volunteers led cattle-drives in 1918.[8]

A Sinn Féin pamphlet published in late 1917 — written by long-time agrarian radical Laurence Ginnell — asked:

‘[w]hy have not the ranches, which are all evicted lands, been distributed among evicted tenants, holders of uneconomic farms, labourers, farmers’ sons and other landless people…’ and admonished ‘young landless people’ to ‘clear cattle off every ranch, and keep them cleared until distributed’.[9]

It wasn’t until the middle of the summer of 1920 that a Dáil decree emphatically ruled against land protests proclaiming that ‘the present time, when the Irish people are locked in a life-and-death struggle with their traditional enemy, is ill-chosen for stirring up strife amongst our fellow-countrymen ; and that all energies must be directed towards the clearing out — not the occupier of this or that piece of land — but the foreign invader of our country’.[10]

Landless people and those evicted would ‘drive’ cattle off large ‘ranches’ and distribute the land among small farmers.

This declaration was very much divergent from what had been the mainstream of nationalism in rural Ireland.

To some a process of land re-distribution was an inherent part of the process of de-colonisation. The ranches were seen as a facet of economic dependence on Britain, as the product of Famine-era clearances, and ultimately of Cromwellian land confiscations.

Land re-distribution was also seen as a central part of economic development, as part of re-orientating agriculture away from a focus on producing cattle for export on the hoof. This was the form of agricultural production with the least potential for spin-off industries as it required the least inputs and needed no processing.

In 1920 land re-distribution itself was not at issue – everyone, including the British government, recognised a need for some land reform —the question was to what extent would land be re-distributed and how would that reform be carried out. Indeed, land re-distribution was, as we shall see, only really questioned by the far-left of the Irish Revolution.

However, the issue of re-distributing land threw up real problems for the various political forces of Irish nationalism. In earlier decades social divisions could be masked beneath an ostensibly unified campaign against landlords —and landlords, for the most part, were not supporters of Irish nationalism and so were easy targets.

The land purchase measures of the various Land Acts from 1870 to 1909 were no solution to people with farms too small to make a living. Hence, by 1920 the main focus shifted to expanding existing farms, or creating new ones, at the expense not only of landlords, but of richer strata of farmers. This posed the potential for opening up divisions within the nationalist camp.

The geography of agrarian conflict

The land movement in 1917‒23 was centred on East Connacht, on the great limestone plain of east Galway, Roscommon and adjacent parts of Mayo. In terms of time, 1920 was the key year. The inequality of farmland distribution was perhaps at its most extreme in East Connacht, but there were protests and conflicts on this issue over much of the country.

For the 1917‒23 period, we can divide the country into two very rough halves along east-west lines, with wage-focused mobilisations more prominent in the east and south and land-focused mobilisations more prominent in the west.

It was in the south and east where there was a greater proportion of farm workers, partly owing to the greater emphasis there on labour-intensive specialised tillage and dairy. An extreme contrast is given by the Delany 500 acre grazing farm, in Dunshaughlin, Meath, with two employees, by contrast with the 72 acre Butterly market garden, near Blanchardstown, Dublin, with at least 15 employees.[11]

The land movement in 1917‒23 was centred on East Connacht, on the great limestone plain of east Galway, Roscommon and adjacent parts of Mayo

On the other hand, beef production could be organised in ways which demanded more labour. For instance, stall-feeding required workers to harvest hay and other fodder crops. This was more likely to be clustered in the east where the later stages of beef production went on. Animals were born in one location, ‘reared’ or ‘brought-on’ in another, and then, ‘fattened’ and ‘finished’ in other locations.

However, to some degree the demand for land was promulgated by farm workers too — seeking an extension of the cottage gardens they had been granted under social reforming legislation going back to the Labourers (Ireland) Act of 1883. Indeed, as there were growing food costs and serious concerns about food supply, even townspeople were looking for land in this period, in the form of allotments and cowplots.[12]

Perhaps particularly prevalent in the East Connacht context was the phenomenon of so-called ‘untenanted land’. This meant land still owned by landlords and either directly farmed by themselves, i.e. demesne farms or home farms, or let out to graziers on the so-called eleven months system. These lands were a major target of the 1920 movement.

Cattle driving and intimidation

The usual tactics of the movement were deputations to property owners to urge them to sell, or to graziers or ranchers to give up the land they were renting as well as cattle-driving which meant herding cattle and sheep off disputed properties. There was also some level of intimidation and sabotage.

So sometimes there was violent intimidation, as in the following examples. On Tuesday March 30th 1920, according to newspaper reports, a two-hundred strong contingent, mostly comprising of tenants of the Ross estate, paraded on horse-back in military formation through the district of Oughterard, Galway, stopping at the residences of large graziers who held lands on the estate, and at the landlord’s house where they held negotiations with the agent.

A Mr. Jackson refused to give up a farm he held at Rosscahill, until threatened with removal to an unknown destination, that is, to a secret prison.[13]

A great deal of violence during the revolutionary period in rural Ireland, including cattle drviing intimidation and even murder, concerned agrarian disputes.

In Headford, just across Lough Corrib from Oughterard, one grazier was told he would be burned alive unless he signed his land over, the assembled crowd, reportedly of over one thousand people, went so far as to start the fire. James G. Alcorn, High Sheriff for County Galway, was brought to the edge of Lough Corrib, and given the choice of drowning or surrendering his farm. In Roscommon one grazier had two pistols held to his head while his prospective grave was dug before his eyes.[14]

The more common tactic of the movement was cattle-driving. Cattle-driving was carried on so extensively that by the middle of April one Galway newspaper could claim that 30,000 acres had been cleared of live-stock — an area equivalent to nearly 50 square miles — and that this involved the driving of 20,000 cattle and as many sheep. Even if this was an exaggeration if such an exaggeration was possible it shows something of the magnitude of the movement.[15]

In early April an especially ambitious cattle-drive took place in south Roscommon — the cattle were to be driven to the square in Athlone to be exhibited as a deterrent. The drivers were dispersed by a charge of police armed with batons and soldiers armed with bayonets, while a Lewis machine-gun was mounted on Athlone castle walls.[16]

By the second-half of April the road between Strokestown and Roscommon was blocked up with free roaming cattle and sheep.[17] One witness described it like so ‘roads and lanes, all over the county, were choked with wandering and half-starved beasts’.[18]

Events in Portumna, in the south-east of County Galway, on the 14th and 15th of April 1920, reveal something of the wider range of targets subjected to action, a wider variety than just landlords or large-scale graziers renting under the 11 months system. This area had been the core of the Clanricarde estate, which had, finally, in 1915, been compulsorily purchased by the Congested Districts Board.

This came after a decades-long struggle during which its eccentric miserly owner, Hubert de Burgh, marquis of Clanricarde, defied his tenants, Parliament and public opinion. De Burgh, who was possessed of a fortune separate from and independent of his estate, was famous for his appearance as ‘a walking scarecrow without crows’ because he mended his own clothes, badly, as a means of saving money.[19]

The Clanricarde estate, therefore, was already controlled by the Board and was in the process of being re-distributed, at issue was who would benefit from this re-distribution. In April 1920 stock was cleared and lands ploughed on the farms belonging to what were known as planters.

These were Ulster Protestants enticed down to take the lands of evicted tenants in the early 1890s. The evicted tenants had been evicted during the course of a rent strike (the strike was part of the Plan of Campaign going on in different localities across the country).

But also targeted was the property of a migrant, someone the Congested Districts Board was moving from one part of the estate to another in its efforts to end the problem of ‘congestion’.[20] All kinds of local disputes, many long-running, could find shelter beneath the overall umbrella of the war on the grassland ranches.

In the environs of Galway town, interesting urban-rural divides became evident. There were fears that farmers in the surrounding countryside would seize the so-called accommodation lands used both by town’s butchers to host animals about to be slaughtered and where the dairymen who supplied the town’s milk kept their cows. There was even suggestion that allotments used by townsfolk to grow vegetables would be taken over.[21]

The major urban-rural clash though, was over the lands of Menlo, which the local government of Galway town wanted as a public amenity, and that local government included Sinn Féin participation, while local farmers, led by one of the most active I.R.A. companies in the county, wanted the lands divided among themselves. In this three-way dispute, caretaker and herdsman James Ward was shot dead at the Gate Lodge in Menlo, his place of residence, in the spring of 1920.[22] He worked for the owner of the disputed lands, Thomas Blake.

So the urban political wing of the republican movement was on one side in the Menlo dispute and the rural military wing of the republican movement was on the other. That brings us to the question of what role the republican movement played in the agrarian mobilisation. It wasn’t just one role, because the republican movement was multi-faceted and divided and diverse as indeed was the agrarian movement.

Republicans and agrarianism

On the one hand, in plenty of places the cattle-drives were organised by the local republicans, but the leadership of the republican movement, on both a county level and on a national level, wanted the situation brought under control and the agrarian movement suppressed.

So in February 1920, for instance, 30 men from the 4th and 5th Battalions, Mid-Clare Brigade, Irish Republican Army, were mobilised to break-up a so-called ‘Independent Brigade’ of their former comrades in the Connolly district, and this ‘Independent Brigade’ was involved in agrarian conflict.[23]

On a similar note, one version of the agrarian situation, given by an I.R.A. officer and recorded by the Bureau of Military History, typifies a haughty disdain ‘[t]he West Clare column did not at any time go west of Kilkee’ – it was not ‘a very healthy area for outside Volunteers’ – ‘the inhabitants revelled in an orgy of disputes, principally agrarian’.[24] Another Bureau of Military History Witness Statement describes the situation in Quilty, which is also in West Clare:

‘In those days it was a thickly populated district mainly comprised of small farmers and landless men such as fishermen and those of the labouring class who depended mainly on kelp burning for a livelihood. Situated in the locality, however, was a good sized non resident grazing farm…’[25]

Men from a company of the I.R.A. from the district of Killmurray were marshalled in defence of that grazing farm, under the command of Roman Catholic curate Father Michael McKenna, who was also an I.R.A. officer. These interlopers were held off by stone-throwing locals, initially at least, until they later returned in force.[26]

Interestingly the owner of the farm in Quilty ascribed her problems to ‘persons calling themselves the Sinn Féin club’, and, when seeking compensation from the British government, talked up her role in supporting the British military.[27]

While come republicans initially backed agrarian ‘cattle drives’, the Dail eventually tried to stop them and to calm land hunger by use of arbitration courts.

As a national initiative, building on localised arbitration courts, Sinn Féin rolled out a more ambitious programme of Dáil land courts. These courts adjudicated in land disputes. The report penned by Roscommon Sinn Féin’ activist Graham Sennett, was part of a lobbying effort for more republican intervention, and was revealingly entitled ‘Regarding Cattle Drivers, Marauders, Terrorists and Hooligans’. It made plain the agenda of enticing ‘every rich man and every landed man, and every employer, and all the class of the men that read the “Irish Times” into the ranks’ of the republican movement.[28]

Tyrone republican Kevin O’Shiel was appointed as a special judicial commissioner for these courts. He admitted that in ‘the vast majority’ of the cases where he ruled in favour of congested small-holders and for the division and sale of lands this was ‘abortive’ as claimants could not meet the prices set by the court valuers.[29]

During the months of May to August 1920 O’Shiel himself ran courts in Ballinasloe, Claremorris, Ballyhaunis, Roscommon, Castlerea, Mullingar, Castlepollard, Birr, Portlaoise, Tullamore, Granard, Longford, Manorhamilton, and Dublin.[30] Further south and west there were yet more courts he was not involved in.

O’Shiel later claimed that the Dáil courts worked because of popular consent. However, his own account of events also claims that the coercive power of the I.R.A. was essential to bolstering the authority of the courts by making an example of some ‘delinquents’ and ‘defiant cases’. [31]

It is just as likely if not more likely that the decisive factor in the decline of the movement was the seasonality of agrarian protest – the springtime of the year, the beginning of the agricultural calendar, was the time-period during in which major mobilisation would take place – as land would have to be in use from then onwards – for the same reason this is when land lettings took place.

The Free State and the land question

In 1922 there was a revival of agrarian mobilisation, so the new Irish Free State inherited this insurgent challenge.

The response of the Irish Free State was much the same as the response of the British state —only more so —that is to say the Free State was to respond with a more biting repression and a more generous reform.

This led to the creation of the Special Infantry Corps, a new gendarmerie for dealing with agrarian and labour disputes in the aftermath of revolution. This was a mailed fist that sits uncomfortably with liberal notions of policing by consent; notions which are important to the images projected by both the British and Irish states.

On the other hand, there was a great expansion of the already existing state programme of re-distributionist land reform. Firstly, in the form of minister for agriculture Patrick Hogan’s Land Act of 1923 and then later there was a further expansion with the 1932 Land Act. In the early decades of the Irish Free State as much as 20% of farmland, one-fifth, was re-distributed.[32]

Through Land Acts in 1923 and 1932, the Free State re-distributed as much as 20% of its farmland, ending a process of tenant purchase that had begun under British rule.

We can see the impact of this policy at its most profound level in those counties which formed the heartland of the 1920 movement. Taking 1901 as a baseline by 1960 there had been a 68% decrease in the number of holdings of 200 acres and over in Galway, a 70% decrease of such in Mayo, and in Roscommon 73%.[33] That is to say the number of the largest tier of farms declined over the course of the first two-thirds of the twentieth century.

It is important to recognise that this represented a solidification of the small-farmer class, the enlargement of the farms of people who already had farms. The genuinely landless agricultural proletariat did not benefit to any great degree from this land reform, excepting very briefly in the 1930s. In fact, the reform may have been some ways inimical to farm workers’ interests as breaking-up large farms made for less employment.

It is also important to recognise that land re-distribution represented at best a stopgap solution to the problems of the small-holders. James Connolly argued that the growth of transatlantic imports would lead to ‘the doom of the petty farmers of Ireland under the capitalist system’.[34] Everything was in fact more complex than that, but, by the 1980s, there was a declining number of farms and an increase in the average size of farms.[35]

The legacy of the land question

The Western Land War of 1920 goes some way to explaining an apparent conundrum —why the populations of some counties were apparently so inactive during the Irish Revolution.

Connacht in general and Galway in particular were some of those apparently inactive areas, but this is only a question, only a puzzle, when the revolution is defined in an utterly narrow fashion as purely about armed clashes between units of Irish Republican Army and the Crown Forces.

With a broader, more expansive understanding of what made up the Irish Revolution, we see that it is simply that those western districts had a different experience of revolution, an experience less congruent with that of Munster and more in-line with nineteenth-century patterns of rural social conflict.

The same can be said of some Leinster counties. Is it true that ‘Meath remained passive throughout’ the revolutionary years? [36] Or was it in fact home to one of the most important rural industrial disputes of the period?[37]

We need a broader understanding of the Irish revolutionary period than purely a story about armed clashes between Irish Republican Army and the Crown Forces

A broader perspective is necessary to capture the diversity of what was actually happening on the ground. Moreover, without putting mass mobilisation in all its myriad forms at the heart of what we mean by the revolution then the term itself is set adrift from its meaning moorings. Revolution cannot be simply defined around violence as how then do we distinguish a revolution from an armed insurrection, or a civil war or a coup d’état.[38]

Such events can be part of a revolution, but the term revolution means something more. For instance, we can define a revolutionary situation around multiple opposing sovereignties, like the rival administrations of the Dáil and the Crown, as well as around mass movements and collective action, like the cattle-drives, or the anti-conscription pledges and general strike,[39] or the I.R.A.’s road sabotage, effective but comparatively unexciting, the more humdrum activity of the typical Volunteer.[40]

Another way to look at revolution is in terms of revolutionary outcomes. Which is to say what transformations in social structure occurred, or were facilitated, through the revolution. Perspectives from both ends of the political spectrum suggest that this section of the story of the Irish Revolution should comprise of blank pages. Certainly, one would have a hard time arguing that the Irish Free State in its opening decades was greatly socially and economically distinct from what it could have been had the 26 counties remained within the United Kingdom.

On the other hand, the re-distribution of 20% of farmland was a fairly significant social reform. Moreover, that reform can be seen as the culmination of processes of change which included, most significantly, the transfer of land ownership to erstwhile tenants. Something which, as we have seen, was still on-going in the 1920s.

Those processes of change began much earlier than the usual periodization of the revolution. Though, that said, they were intimately bound up with the beginnings of, and course of, consistent, widespread and deep nationalist mobilisation in much of rural Ireland, something which might be said to have culminated in the revolutionary years.

We can turn this question around and look at it from another perspective. During the controversy over the proposed commemoration of the Royal Irish Constabulary some comment made plain that the R.I.C. were a very different force from putatively normal police forces like the Gardaí.

What we have to consider though, is how different were the societies which the respective forces had to police. While our stereotype of mid-twentieth century Ireland is of sleepy conservatism, our stereotype of nineteenth-century Ireland is of burning hayricks.

These are stereotypes but they contain kernels of reality. What made the change? Was it the painting of green post-boxes or was it new ways of acquiring green fields? If the latter, then was this the real revolution?

Terry Dunne studies agrarian social movements, and has a Phd. in sociology from Maynooth University. This article is based on the same research as Prairie Fire, episode two of his podcast Peelers & Sheep.

https://peelersandsheep.ie/podcast/ep-2-prairie-fire/

References

[1] Quoted in Terence Dooley, ‘The Land for the People’: The Land Question in Independent Ireland (University College Dublin Press, 2004) p. 204.

[2] Dooley, ‘The Land for the People’, p. 28.

[3] Not only on a national scale, but on a local scale too i.e. the best land of any district would be in the largest farms see the following for evocative descriptions of that situation — Kevin O’Sheil, Bureau of Military History (hereafter BMH) Witness Statement 1770, pp. 929-930; Labhras Mag Fhionnghail (Laurence Ginnell), Leaflet No. 8 The Land Question (Sinn Féin, n.d.).

[4] Dooley, ‘The Land for the People’, p. 19.

[5] Anthony Varley, ‘The Politics of Agrarian Reform: The State, Nationalists and the Agrarian Question in the West of Ireland’ (Phd. Thesis, 1994, Southern Illinois University) p. 232. This thesis is available in N.U.I. Galway library. As well as those listed Varley also identifies more purely political factors — growing conflict between the state and republicans, and the perception Sinn Féin would support re-distribution.

[6] Quoted in Dooley, ‘The Land for the People’, p. 41.

[7] For discussion of the social composition of nineteenth-century agrarian movements see James S. Donnelly Jr., Captain Rock: The Irish Agrarian Rebellion of 1821 – 1824 (Collins Press, 2009) pp. 10‒18; Samuel Clark, ‘Strange bedfellows? The Land League alliances’ in Fergus Campbell and Tony Varley (eds) Land Questions in Modern Ireland (Manchester University Press, 2013) pp. 87-116. For farm workers’ movements in the later decades of the nineteenth-century see local history journal articles by Pádraig G. Lane and several book chapters by Fintan Lane.

[8] Pádraig Óg Ó Ruairc, ‘“The road for the cattle – the land for the People” The Castlefergus Cattle Drive and the death of IRA Volunteer John Ryan’, https://www.theirishstory.com/2018/03/02/the-road-for-the-cattle-the-land-for-the-people-the-castlefergus-cattle-drive-and-the-death-of-ira-volunteer-john-ryan/#.X7v2MRbgrIV, Accessed 23/11/20.

[9] Mag Fhionnghail, The Land Question, p. 12, p. 19.

[10] Ibid. p.1011.

[11] W.E. Vaughan, ‘Farmer, Grazier and Gentleman: Edward Delany of Woodtown, 1851‒99’ in Irish Economic and Social History Vol. IX (1982) p. 67.

[12] There was a government measure providing for allotments see: Mary Forrest, ‘Land Allotment Scheme in Cork city 1917-1923’ in Journal of the Cork Historical and Archaeological Society Vol. 124 (2019) pp. 27–44.

[13] Connacht Tribune Apr. 3, 1920.

[14] Varley, ‘Politics of Agrarian Reform’, pp. 242‒243.

[15] Fergus Campbell, Land and Revolution: Nationalist Politics in the West of Ireland 1891-1921 (Oxford University Press, 2005) p. 253.

[16] Connacht Telegraph Apr. 10, 1920.

[17] Strokestown Democrat Apr. 24, 1920.

[18] Quoted in Campbell, Land and Revolution, p. 165.

[19] Miriam Moffitt, Clanricarde’s Planters and Land Agitation in East Galway, 1886–1916 (Four Courts Press, 2011) p. 11.

[20] Connacht Tribune Apr. 17, 1920.

[21] Connacht Tribune Apr. 17, 1920.

[22] McNamara, War and Revolution, p.172.

[23] Patrick Devitt, BMH Witness Statement 1044, p. 4; Seamus McMahon, BMH Witness Statement 984, p. 6.

[24] Liam Haugh, BMH Witness Statement 474, p. 38.

[25] Joseph Daly, BMH Witness Statement 1253, p. 3.

[26] There is another account of these events in: Eamonn Gaynor, Memoirs of a Tipperary Family: The Gaynors of Tyone (Geography Publications, 2003).

[27] Clare Library Local Studies, Irish Grants Committee CO 762 — County Clare extracts Page 294, Dora Adelaide Brews. The dispute at this farm, known as ‘Seafield’, continued at least into the civil war period see John Dorney, ‘‘Rough and Ready Work’ – The Special Infantry Corps’ https://www.theirishstory.com/2015/10/15/rough-and-ready-work-the-special-infantry-corps/#.X7Ls1hbgq01 Accessed 16/11/20.

[28] Quoted in Kevin O’Sheil, BMH Witness Statement 1770, pp.975-979.

[29] Ibid. p. 1036

[30] Ibid. p. 959.

[31] Ibid. p.961, details of the incident are across pp. 961‒966 and pp. 948‒956.

[32] Dooley, ‘Land for the People’, p. 20.

[33] David Seth Jones, Graziers, Land Reform and Political Conflict in Ireland (Catholic University of America Press, 1995) p. 221.

[34] James Connolly, ‘Capitalism and the Irish Small Farmers’ (1909) online at: https://www.marxists.org/archive/connolly/1909/11/irshfrmr.htm, accessed 27/10/20.

[35] Central Statistics Office, Farming Since the Famine: Irish Farm Statistics 1847‒1996 (Stationary Office, 1997).

[36] Peter Hart, ‘The Geography of Revolution in Ireland 1917-1923’ in Past & Present 155 (May, 1997) p 154.

[37] Terence M. Dunne, ‘Emergence from the Embers: The Meath and Kildare Farm Labour Strike of 1919’ in Saothar: Journal of Irish Labour History 44 (2019) pp. 59‒68.

[38] For social science discussion of what constitutes a revolution see: John Foran, Taking Power: On the Origins of Third World Revolutions (Cambridge University Press, 2005) pp. 5‒29; Charles Tilly, From Mobilisation to Revolution (Random House, 1978) pp. 189‒222.

[39] Padraig Yeates, ‘‘HAVE YOU IN IRELAND ALL GONE MAD’ – the 1918 General Strike Against Conscription’ in Saothar: Journal of Irish Labour History 43 (2018) pp. 47‒53.

[40] W.H. Kautt, Ambushes and Armour: The Irish Rebellion 1919–1921 (Irish Academic Press, 2010) pp. 77‒79.