Mary Dunne, A Mother’s Struggle for Recognition

By Martin Harkin

The mystery and conspiracy that surrounds the shooting of Field Marshall Sir Henry Wilson on 22nd June 1922 has absorbed many historians and researchers in their efforts to uncover some clarity on who ordered the killing.

What led to Reginald Dunne and his comrade Joseph O’Sullivan to undertake such an operation? The two former British soldiers waited for Field Marshall Sir Henry Wilson to arrive back to his home at Eaton Place in Belgravia. As the former Chief of the Imperial General Staff climbed the steps to his front door, Dunne and O’Sullivan stepped forward and shot him dead.

Reginald Dunne and Joe O’Sullivan were hanged for their June 1922 killing of Henry Wilson in August of that year

The gunmen were swiftly captured while attempting to escape and were subsequently found guilty at their trial in the Old Bailey and sentenced to hang. The repercussions of their deed caused the British government to issue the Provisional Government in Dublin with an ultimatum to move against the anti-Treaty force in the Four Courts and culminated in the outbreak of fighting in Dublin on 28th June 1922, sparking the Irish Civil War.

But what happened to the families of the condemned Volunteers? For Mary Dunne, the mother of Reginald Dunne, her life following the death of her son consisted largely of sadness and impoverished circumstances. Mary was fifty when her only child Reginald was sent to the scaffold in Wandsworth Prison. She spent much of the remainder of her life fighting for recognition of her son’s actions and battled with enormous bureaucracy from the Irish Government in her efforts to draw financial aid to support her existence.

Mary Dunne’s early life

Mary Dunne was born in 1872 in London. Her father William was born in Ireland in 1839 and was long settled in the city having left his home as a young man.

At the time of her death, it was reported in the Evening Herald that locals in Co. Monaghan believed that a particular townland, Greenans Cross, derived its name from an ancestor of Mary’s who was executed at the locality.[1] In 1897 Mary married a career soldier named Robert Dunne who was twenty years her senior.

Mary Dunne was born in London in 1872 of an Irish father.

Seven years into their marriage, Robert retired from the army after serving thirty years, twelve of which had been spent overseas in India. Robert had been a bandmaster with the 3rd Dragoon Guards. Following his long service, Dunne senior was discharged from the army in 1905 at the age of 53 with a handsome annual pension, £123 5s 6d per annum. His discharge notes recall ‘exemplary’ service, and the award of six good conduct badges.[2]

Mary gave birth to her one and only child, Reginald William Dunne in June 1898. Like his mother he was born in Woolwich. During the trial of Reginald and Joseph O’Sullivan, many press outlets labelled them as ignorant and uninformed thugs.

‘Well educated young men’

In contrast, both were well educated young men. Dunne had attended the Jesuit run St. Ignatius College, Stamford Hill prior to joining the British Army. As a student he particularly excelled in English and was awarded a gold medal for his essay writing in his final year.[3]

After being demobilised, Dunne studied to become a teacher at St Mary’s College, Hammersmith. This college was administered by the Vincentian order. The modern incarnation of this institute is now St Mary’s University, based in Twickenham. Dunne’s educational life was shaped by strong sense of Catholicism and religious devotion.

Reginald Dunne was well educated, a devout Catholic and served in the British Army in the First World War. He was a late convert to Irish republicanism

However, he never completed his studies and left the college before qualifying as a teacher in order to devote his energy to the newly reorganised Irish Volunteers in London. Reginald was one of the first to join and quickly rose to become Commandant of the newly named London Battalion IRA, leading regular drills and parades across the city.

In her witness testimony to the Bureau of Military History Collection, Mary MacGeehin offers a close and personal insight into her friend Mary Dunne’s family. MacGeehin had served as Secretary of the Gaelic League in London from 1920 through to the Treaty period in addition being an active member of Cumann na mBan. She recalled how the Dunne family and Reginald in particular held no great revolutionary zeal prior to the War of Independence.

Their passion was music, largely influenced by Robert’s role as bandmaster in the army. They had in fact performed as a musical trio, Robert played a wind instrument, Mary the piano and young Reginald played the violin. He held onto his violin until his execution, bequeathing it as a gift to his solicitor in August 1922.[4]

Grief and unsettlement

Like any mother, Mary was hit particularly hard following the death of her only child. Shortly after Reginald was hanged, his London born parents left their home to settle in Ireland. According to MacGeehin, this was in accordance to the wishes of their late son.

Mary and Robert settled in Bray, Co. Wicklow where they rented a small terraced house in the town. In her witness testimony, MacGeehin further recalled how they couple were visited shortly after settling in by two men. It is believed that these two men were Tom Cullen and Liam Tobin.

The Irish authorities arranged informally, via Intelligence officers Liam Tobin and Tom Cullen, for Mary Dunne and her husband Robert to settle in Ireland after their son’s execution.

Both were veterans of the War of Independence, and had served under Collins in the Intelligence Department. Cullen and Tobin sided with their former Chief and fought for the Free State forces during the Irish Civil War, reaching the rank of Major-Generals respectively. During the visit, they handed Mary Dunne the deeds to the house as a gift, expressing their regret that nothing public of official could be done in the circumstances.

The fact that these two prominent figures personally visited the Dunne household with the deeds to their home as a form of payment for the sacrifice made by Dunne and O’Sullivan strongly alludes to an acknowledgement on behalf of former IRA officers they acted under official orders. Drawing from the witness statement, it can be argued that this gesture was a discreet form of compensation and recognition.[5]

Perhaps as result of their grief, Robert and Mary were unable to settle in Bray. They sold their house and returned to live in England. However, within a year they had returned to Ireland, settling in Howth, Co. Dublin.

Yet this was to prove temporary as the couple left for England once more to live with Mary’s sister. Nevertheless, this too proved short lived, as Mary and Robert returned across the Irish Sea to finally relocate in Havelock Square, Sandymount. It was at this address that Mary lost her husband on 9th September 1934.

Now a widow and in her sixties, Mary found herself in dire financial straits. Her sole source of income was a weekly pension of a meagre 11 shillings a week.[6] It is quite possible that were it not for the kind generosity of friends and donations from the Irish community in London, she would have found herself on the streets. Tormented by her grief from losing her husband, Mary Dunne left her home in Sandymount and moved between friends in Stilorgan and her sister in London before returning to Howth, where she remained until her death in May 1939.

The quest for a military pension

Shortly before the death of her husband, Mary applied for a pension of behalf of her son’s death on active service in London. She had been encouraged by The Army Pensions Act, 1932, which unlike previous legislation was open to all those who participated in the War of Independence.

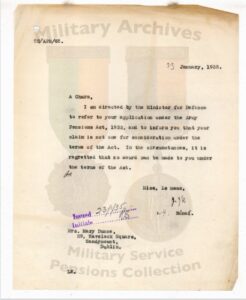

Any hopes of a swift response from the authorities were quickly dashed. After two years of correspondence and tortuous bureaucracy, Mary’s application was rejected by the Military Service Registration Board in January 1935. It was judged that her case did not fall under the remit of the existing legislation and no financial award could therefore be made.

In her submission on behalf of her old friend, Mary MacGeehin informed the board that she had been named as one of three people in Reginald’s last will and testament to take care of his mother, but she was in no financial position to do so.

In 1937, Mary applied for a dependent’s pension due to the death of her son on IRA service, was but was rejected.

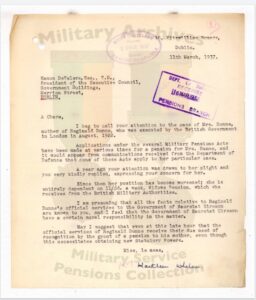

She wrote in February 1935 that they were led to believe that Reginald had received a guarantee that his mother would be looked after should be killed as a result of his active service[7]. Another of Mary’s friends, Kathleen Whelan wrote to De Valera directly in March 1937, days after he assumed the role of President of the Executive Council of the Irish Free State.

Whelan informed him of the plight of Mary Dunne, and the sacrifice made by her only child as an officer in the IRA. Her sole income was her weekly widows’ pension from the British Government, a mere 11 shillings 6d, and that several unsuccessful applications had been submitted under the various Military Pensions Acts.

She implored that some concession be made on Mary’s behalf even if it involved new legislative and Statutory Powers[8]. This letter was subsequently passed to the Minister for Defence Frank Aiken for his attention. Unfortunately, the reply from Aiken’s office in April 1937 stated that there were simply no funds available for compensation.

Despite this setback, the campaign to help Mary Dunne continued. In February 1938 Mary received word from Frank Aiken’s department to apply once more under Part VII of the Army Pensions Act, 1937. A new application was submitted to the Board, and Mary clearly outlined her financial situation. She wrote in February 1938 explaining that if Reginald were still alive, he would have duly supported her, but Ireland had deprived her of a son.

She described how Reginald had lived at home all his life, and other than serving in the British Army and subsequently in the IRA, had never been employed. In her correspondence, Mary recalled learning that Reginald had been receiving payments from Ireland.[9]

Her case however, was ultimately once again unsuccessful. In July 1938 the Board ruled that under the legislation they were unable to recommend an award to Mary Dunne. Under the guidelines, no awards could be made to those with earnings greater than £40. Her widows’ pension and donations received by her friends was calculated to an annual income of £43 8s[10].

Aiken intervenes

That appeared the settle the matter once and for all, except for the direct intervention of Frank Aiken and his Department. They expressed their desire for Mary’s means to be reassessed and felt it very harsh that she be penalised for receiving money from friends.

The previous legislation had subsequently been amended to consider dependents such as Mary Dunne. Part VII of the Army Pensions Act, 1937, allowed for claims on behalf of the deceased.

It appears that Minister for Defence, Frank Aiken finally insisted to the Department of Finance that Mary Dunne’s claim be accepted.

A note from the Minister for Defence’s office stated that if necessary “a firm stand on the matter should be taken with the Department of Finance”.[11]

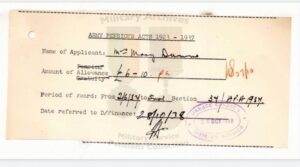

Aiken’s intervention was resulted in a revaluation of Mary’s circumstances and she was finally awarded a special dependents allowance of £6, 10s on 12th October 1938. After five long years of applications, appeals and the generous support of her friends, the State finally acknowledged Mary’s loss and the sacrifice of Reginald Dunne.

Death

In early May 1939, Mary Dunne died. Her death came four weeks before she was due to receive the first payment of her special dependents allowance from the Irish Government. Her life had been blighted by tragedy and financial hardship.

Mary died four weeks before she was due to receive her first payment from the Irish government in May 1939.

Following her son’s execution and the death of her husband, Mary could never truly settle and find comfort. Left a widow and scraping by on a meagre pension, she sought for five years to have Reginald’s sacrifice recognised. She was buried in Deansgrange cemetery in Dublin before a large congregation of mourners. Present at the funeral were veterans who were active in the IRA in London and in Scotland.

Patrick Little TD attended as De Valera’s official representative. Moreover, Liam Tobin was also present as were representatives of the Department of Finance.[12]. Almost three decades later, the remains of Mary’s beloved son Reginald was repatriated to Ireland together with those of his comrade in arms Joseph O’Sullivan and buried with great publicity in Deansgrange cemetery in 1967.

References

[1] Evening Herald 5 May 1939

[2] Royal Hospital Chelsea Pensioner Admissions and Discharges, 1715-1925

[3] Mary MacGeehin, WS902, Military Archives Ireland

[4] Mary MacGeehin, WS902, Military Archives Ireland

[5] Mary MacGeehin, WS902, Military Archives Ireland

[6] Mary MacGeehin, WS902, Military Archives Ireland

[7] Mary MacGeehin, WS902, Military Archives Ireland

[8] Kathleen Whelan letter to De Valera

[9] Mary Dunne reference

[10] Relevant reference

[11] Relevant reference

[12] Evening Herald 6 May 1939

All images courtesy of Military Service Pensions Collection, Military Archives.