Revisiting the ‘Limerick Pogrom’ of 1904

By Seán William Gannon

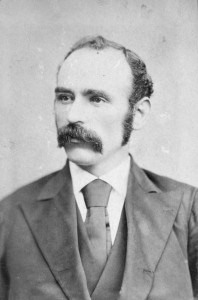

On the evening of 11 January 1904, Fr John Creagh took the pulpit during mass at the Redemptorist church at Mount St Alphonsus in Limerick. His congregation comprised the weekly meeting of the ‘Monday Division’ of the Arch-Confraternity of the Holy Family, a 6,500-strong male sodality which, under his then spiritual direction, was a powerful force in the city’s Catholic life.[1]

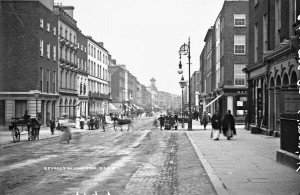

Attendance that evening was unusually high for Creagh had promised ‘startling revelations’ on a ‘special subject’ the previous week.[2] Minutes into his sermon, this ‘special subject’ became clear – Limerick’s Jewish community centred on Colooney Street, a short walk from his church’s front door.

According to the widely accepted version of events, Creagh delivered a virulent antisemitic diatribe which gave rise to a pogrom and inaugurated a two-year economic boycott of the Limerick Jewish community. This boycott compelled most Jews to leave the city, sending the community into terminal demographic decline.

A boycott in Limerick in 1904-1905, compelled most Jews to leave the city, sending the community into terminal decline

This version derives largely from claims made at the time. These claims were challenged contemporaneously, and more recently by local historians in Limerick who argue that the traditional narrative of Limerick 1904 is based on a series of misconceptions and misrepresentations which unfairly sully the city’s reputation. This article explores the most significant issues in contention and concludes that the truth lies somewhere between the competing claims.

Creagh’s sermon

What Creagh said on 11 January is not in dispute as his sermon was comprehensively reported in the local press. He began with some general pieties about loving one’s enemies before warning that this Christian principle should not blind a people to dangers in their midst.

According to Creagh, the primary danger in Limerick then took the form of the Jews. Until recently known only by ‘name and evil repute’, they had come ‘to fasten themselves on us like leeches and to draw our blood’ and, unless something was done, ‘we and our children [would become] the helpless victims of [their] rapacity’.

Having arrived in Limerick 20 years previously ‘apparently the most miserable tribe imaginable with want on their faces’, they had quickly enriched themselves and could today ‘boast of very considerable house property’ around the city. ‘Their rags have been exchanged for silk. They have wormed themselves into every form of business … and traded even under Irish names’.[3]

Fr. John Creagh said of the Limerick Jews: they had come ‘to fasten themselves on us like leeches and to draw our blood’ and, unless something was done, ‘we and our children [would become] the helpless victims of [their] rapacity’.

Creagh then proceeded to read from a press report of a recent Jewish wedding which contrasted the ‘fine broadcloth in silks and satins’ worn by the guests with the ‘poverty’s motley’ of the onlooking crowd.[4]

The wealth that this finery represented was accumulated through the ‘weekly payment system’ (i.e., hire purchase or credit trading), a sinful, unscrupulous business method through which buyers were effectively trapped into paying multiple times for already over-priced items lest they end up in court.

Hence, the people of Limerick should terminate outstanding ‘transactions’ with Jewish credit traders as soon as they could and have no further business dealings with them in the future. As Dermot Keogh and Andrew McCarthy observed, ‘in the country that invented the phrase, this was nothing short of a call for a boycott’.[5]

The focus of contemporary debate was on the character and intent of Creagh’s exhortation. One week afterwards, on 18 January, the Freeman’s Journal published a letter by Michael Davitt roundly condemning Creagh’s remarks.

For Davitt (one of a number public figures whom Limerick Hebrew Congregation minister Elias Bere Levin had petitioned for support), they were representative of a ‘spirit of barbarous malignity being introduced into Ireland under the pretended form of a material regard for the welfare of our workers’.[6]

A highly indignant Creagh took the pulpit that night and gave a second sermon to the Arch-Confraternity flatly denying what he saw as Davitt’s implication that his first had been delivered with broad antisemitic intent. On the contrary, he insisted, his sole aim in speaking was ‘to save the Confraternity men from the ruinous trade of the Jews and the Jewish religion as a religion had nothing whatever to do with his statements’.[7]

Religious hatred or ‘trade methods’?

Creagh steadfastly maintained this position afterwards and it became a mantra for his defenders, most prominently the Limerick Leader which insisted that ‘the whole Jewish question is not one of faith or belief, but one purely and simply of trade methods’.[8]

The Royal Irish Constabulary too took Creagh’s claim at face value: on reading his second sermon, the deputy-inspector general in Dublin Castle, Heffernan Considine, decided that Creagh had instituted the boycott, ‘not so much because they are Jews as because their methods of dealing are in his judgement injurious to the poorer classes’ and local RIC reports on the boycott sent him in subsequent months confirmed him in the view that ‘the methods of business practised by the Jews are entirely responsible for the agitation’.[9]

The Royal Irish Constabulary thought that ‘the methods of business practised by the Jews are entirely responsible for the agitation’

Yet if Creagh’s sole concern was what he perceived to be the economic exploitation of the poor through ‘usurious percentage’, he needed have looked no further than his own flock. Limerick’s leading private lenders were Christians and ‘the credit extended by non-Jewish traders … dwarfed that supplied’ by Jews.[10]

Creagh claimed in his first sermon that Limerick’s Mayor’s Court of Conscience (where small debts were recovered) had become ‘a special court for the whole benefit of the Jews’, who had taken 337 actions there in 1902 and 226 in 1903. These figures cannot be verified as the court ledgers for 1900-1908 have, mysteriously, been lost.

What is clear is that an analysis of this court’s records for the periods prior to and post-1904 (viz. 1895/99 and 1909/17) indicates that Jewish traders were not then over-represented in terms of summonses issued.

Nor were they over-represented in terms of county court actions, comprising ‘only a small fraction of the cases taken against debtors in Limerick city circuit court in the years before the boycott’.[11] Indeed, Levin provided figures of 31 of 1,387 in 1903 and 8 of 300 at the 1904 Easter sessions which, although spuriously contextualised, were not disputed by the Creagh side.[12]

Moreover, while Creagh’s sermons may have been primarily directed against ‘Jewish trading methods’, it is abundantly clear from their texts that he had Judaism itself in his sights. His first sermon’s tirade against these ‘methods’ was carefully contextualized with Catholic theological Judaeophobia and the continental antisemitic conspiracy theory of the time: he had evidently been deeply influenced by the antisemitism prevailing in French clerical circles during the Dreyfus Affair.

Creagh denounced the Jews as divinely rejected Christ-killers and the ritual murderers of Christian children, the ‘greatest haters of the name of Jesus Christ and of everything Christian’ who, in league with the Freemasons, worked tirelessly against Catholic interests through the corruption of morals and other means.[13]

Furthermore, his second sermon, framed as a point-by-point rebuttal of Davitt’s antisemitism charge, was itself so antisemitic that the secretary of the London Committee of Deputies of the British Jews, Charles Emanuel, described it as ‘perhaps the grossest insult to the Jewish religion which has been offered in any civilised country within [its] memory’.[14]

Creagh claimed that the Jews had endured for 2,000 years as Christianity’s inveterate enemies and ‘Catholics were being persecuted this very day by the power of the Jews and Freemasons of France’; and, although he protested what he termed Davitt’s ‘false assertion’ that he had ‘insinuated ritual murder’ (which he had), he went on to discuss several ‘examples’ taken from the works of two of the Church’s ‘greatest historians’ to demonstrate that it was a Talmud-sanctioned historical fact.[15]

Defending Creagh in the mid-1980s, the Redemptorist historian Michael Baily described all of this as ‘regrettable sectarian pulpit oratory … the stock in trade of [Catholic] polemics at the time’ and there is certainly some truth in this.[16] However, Creagh’s conscious inclusion of antisemitic tropes in targeted anti-communal invective was culpably reckless and, although he ‘deprecated’ violence in sermon and interview, he bore full responsibility for that to which it gave rise.

As Emanuel complained to the Irish Chief Secretary, it was ‘hardly possible to imagine an attack of more revolting nature or one more likely to inflame the minds of the audience and to lead to a breach of the peace’.[17] This was particularly true of Limerick, a city in which (as Creagh, as a native, was certainly aware) Catholic feeling towards the Jewish community periodically ran high and assaults on members were not uncommon.[18]

An Irish ‘pogrom’? Violence against Jews in Limerick

The nature and scale of the violence Creagh caused has generated considerable debate. In April 1970, Gerald Goldberg[19] (whose family lived in Limerick in 1904) characterized it as a ‘near genocide perpetrated … against some 150 defenceless Jewish men, women and children’.[20]

Although he became somewhat more considered on the subject over the next 30 years, his continuing view of the violence as essentially pogromist strongly shaped the canonical historical narrative, not least through his importance as a research source for historians such as Jim Kemmy and Dermot Keogh.

Sustained objection to the term ‘pogrom’ emerged locally in the mid-1980s when, citing dictionary definitions (which generally refer to organised massacres), Michael Baily described it as an ‘emotive … misnomer for minor disturbances’ and other Limerick historians agreed.

Whether the events in Limerick merit the term ‘pogrom’ is matter of some debate to this day.

For example, in a most extraordinary discussion of the events, Criostoir O’Flynn dismissed the violence as limited, low-level ‘public harassment’ while Des Ryan, whose pioneering research on Limerick’s Jewish community provided an important reference point for subsequent studies, rejected the term out of hand.[21]

An examination of contemporary archival sources does indicate the violence perpetrated was, in terms of ‘seriousness’, towards the lower end of scale.

Two days after Creagh’s first sermon, Elias Levin complained to Limerick‘s RIC county inspector, Thomas Hayes, that several members of his community had been ‘insulted, assaulted and abused with menacing language’, while local press, RIC, and court of petty sessions’ reports and records mainly describe incidents of jeering, spitting, jostling, and mud throwing, often by women and children. Indeed, the Limerick Chronicle, which strongly condemned Creagh’s campaign, referred to ‘outbreaks of silly women and hobbledehoys’.[22]

However, it also reported an episode of stone-throwing in which ‘Israelites had very narrow escapes’ and court of petty sessions registers record prosecutions for stonings and some physical beatings, as did the RIC. It should also be noted that, while what one magistrate termed this ‘intimidation and terrorization’ of Jews was generally sporadic, it was conducted on at least one occasion by ‘dangerous’, ‘riotous and disorderly’ crowds 200 to 300 strong.[23]

The fact that the RIC believed that worse violence was prevented only by its presence is also very significant in this regard. For although the founder and director of the Irish Mission to the Jews, I. Julian Grande, subsequently accused the police of taking a passive approach to the situation, they actively, and very effectively, intervened to protect Limerick’s Jews.[24]

On 16 January, District Inspector Charles O’Hara visited a number of stations and gave their sergeants ‘special instructions as to looking after the Jews and affording them every protection’ and RIC and court reports record several instances where violence against Jews was by them forestalled, particularly on 18 January.[25]

The disturbances became increasingly spasmodic as a direct result of police interventions and, by 22 January, the RIC was reporting that ‘no further demonstrations against the Jews have taken place’ and that they had been ‘transmitting their business without molestation for the last few days’.[26] The Limerick Leader proclaimed ‘Peace in the City’ five days later, Jewish traders ‘transacting their business in the usual way’, while the Limerick Chronicle reported that ‘the annoyance has entirely ceased’.[27]

Julian Grande told The Times that no member of the Jewish community could ‘walk along the streets … without being insulted or assaulted’

This cessation was, however, by no means complete. For although Creagh told the Northern Whig in early February that ‘the Jews of Limerick need have no fear of violence’, intimidation and assaults persisted for another six months.[28]

The extent of this violence was hotly contested. After spending a week with the Limerick Jewish community in late March, Julian Grande told The Times that no member could ‘walk along the streets … without being insulted or assaulted’.[29] However, District Inspector O’Hara dismissed this as ‘a gross exaggeration’ and Grande’s claims and similar were strongly denied by others on the ground.[30]

For example, the city mayor told a special meeting of Limerick Corporation that there was ‘no violence being offered to the Jews in Limerick … and statements made in court and appearing in some sections of the press as to assaults being committed were unfounded and untrue’.[31]

The Limerick Leader agreed, denouncing the portrayal of the city as in ‘a state of siege’, its Jewish community ‘stoned, mobbed, boycotted and starved’, while the Limerick Echo fulminated against ‘Jewish propaganda of libel on the peaceful character and Catholicity of the city’.[32]

Meanwhile the chairman of the quarter sessions, Judge Richard Adams, who was in Limerick throughout May, said that there had been ‘gross exaggerations on both sides’, and he refused to hear any more of what he termed ‘those Jew-Christian cases’ which, he believed, only served to stir up further trouble ‘which was happily dying away’.[33]

What can be said with certainty is that between 40 and 50 sporadic anti-Jewish incidents were reported between February and July 1904, a very small number of which caused some degree of ‘bodily harm’. Indeed, Levin was himself then stoned on two documented occasions and again in July 1905.[34]

Boycott and the Jewish ‘exodus’

But for Elias Levin and Charles Emanuel, ‘the most serious aspect of [Creagh’s] work’ was not the violence, but ‘the boycott which he so successfully instituted’ and its scope and scale was also the subject of dispute at the time.[35]

In terms of scope, Levin claimed that it constituted a ‘general boycott’ against the entire Limerick community, but this was denied by Creagh and his defenders who maintained that it targeted only ‘a class of Jewish traders who grind and oppress … the unfortunate’, viz. money-lenders and credit traders.[36] Credit traders certainly bore the boycott’s main brunt.

On 18 January, Levin informed County Inspector Hayes that those ‘who trade on the weekly payment system [were] literally ruined’ (they had ‘hardly collect[ed] 10% of their usual’ instalments) and that new sales were ‘out of the question … not one shilling’s worth of goods having been sold’; and RIC and court reports confirm that some people did grasp the opportunity provided by the boycott to default on such debts.[37]

Jewish businesses did suffer from the boycott but the decline of Limerick Jewish community was a result of a number of factors.

But the targeting of Jewish credit traders and lenders amounted to a community boycott de facto as, with few exceptions, its breadwinners worked as one or both.

The RIC reported the same day that around 40 Jews went out collecting installments, a figure which represented around 80 per cent of the community’s adult male population, while an examination of contemporary press advertisements and court records and reports indicates that several of those who gave their occupations as pedlars and (travelling) drapers on the 1901 census operated as lenders as well.

Furthermore, although larger businesses such as Philip Toohey’s City Furnishing Warehouse and at least one of two (it appears competing) dental practices owned by Jaffe families were exempted, the city’s small Jewish shops were, initially at least, included in the boycott too.[38]

Levin reported to Hayes on 18 January that their ‘ruin [was] already visible, having lost all their Christian custom since [Creagh’s] first address’ and, although Levin’s claims must be treated with caution, there is some corroboration of this in two cases: Marcus Blond, the president of the Limerick Hebrew Congregation who ran a shop on Henry Street, told The Times in April 1904 that he had lost all of this trade.

The grandson of Solomon and Sarah Aronovitch recalled the boycott’s impact on their Colooney Street shop 80 years later: ‘They had a lot of non-Jewish customers, but after Creagh’s speeches, none came and none paid their small Christmas accounts and they lost all their business’.[39]

The archival record also indicates there was at least some truth in Levin’s claims that (1) suppliers with whom Jewish shops had ‘dealt for years on credit’ were now declining to do so and calling in outstanding debts, and (2) some farmers were refusing to supply them with milk. And while there were press reports that Jewish children at Limerick’s Model School were being shunned by their classmates on account of the boycott, hard evidence has yet to emerge.[40]

The ‘Creagh boycott’ certainly had broad popular support. According to one of the early historians of Limerick 1904, ‘a few brave Catholics refused to be intimidated’ and ‘a very small minority [of] … Colooney Street residents remained on friendly terms with the Jewish neighbours’, but no references are provided for the statement.[41] Some lay Catholic priests did disapprove of Creagh’s campaign and (at least) pledged to advise their congregations ‘not to interfere with or molest the Jews’.[42]

Public criticism of the boycott of Jewish businesses in Limerick was largely confined to its Protestant communities.

However, public criticism in Limerick was largely confined to its Protestant communities: the local Church of Ireland bishop, Dr Thomas Bunbury, offered strong (if rather ill-informed and certainly counter-productive) support to the Jewish community, as did the unionist Limerick Chronicle, and Protestant lawyers tended to take its part in the courts.

This support was, perhaps, in itself not an insignificant factor in near-blanket backing for Creagh amongst Limerick’s Catholic population, as well as in nationalist newspapers such as Limerick Leader, Limerick Echo, and Munster News. And while the studied ambivalence of Limerick’s Catholic bishop, Dr Edward O’Dwyer, saw him decline publicly to intervene, the hierarchy of the Redemptorist order was sympathetic to Creagh.[43]

In terms of scale, Levin and his supporters presented the ‘Creagh boycott’ as sustained and devastatingly successful. Almost three months after its launch, Julian Grande complained to the press that it was still ‘in full force’, not just in the city, but throughout Limerick county as well, with the result that all but a handful of Limerick’s 35 Jewish families were ‘ruined and on the verge of starvation’.[44]

Emanuel reported on this to the Irish chief secretary at the same time. By his account, the destruction of the community was almost complete: 20 of the 35 families (comprising 100 individuals) were ‘entirely ruined’ and solely reliant on charitable support, and that it was ‘impossible to conceive that these unfortunate people [could] earn their livelihoods [there] in the future’.[45]

Then in July, Levin wrote the visiting superior general of the Redemptorist order, Fr Mattias Raus, that it was ‘useless for a Jew to keep open his shop for any trade, for the Catholic people who were their customers [would] no longer deal with them’.[46]

RIC records only partially corroborate these claims. Addressing Grande’s ‘highly coloured’ presentation, the sergeant at William Street barracks reported to District Inspector O’Hara that, while the Jews ‘are practically doing no business and in trade matters are left severely alone’, their situation ‘is not, in any instance, “appalling”. Some of them are very poor but none are in want’.[47]

O’Hara subsequently reported to County Inspector Hayes that ‘Jewish trade has fallen away largely but there is no general boycott of the Jews’. Credit traders were being paid their instalments ‘in many cases’, although no new business was being currently transacted. In his view, the boycott would crumble if Levin and Grande allowed things to ‘quiet down’, as the poorer classes with whom Jewish credit traders and lenders mainly dealt could not easily ‘pay ready money in shops’.[48]

But the situation remained difficult a year later. According to a Dublin Castle report of 13 March, ‘[Jewish] trade in the city is ruined: in the country except close to Limerick City, it has fallen off’. The Jews were ‘as a general rule … left severely alone’.[49] It is unclear from the available archival record as to when the boycott began significantly to relax. However, the indications are that (as Levin had predicted three months in) it remained in force in some form until Creagh left Limerick in April 1906.[50]

In the early months of the boycott, Creagh declared that ‘the Jews are a curse to Limerick, and if I am the means of driving them out, I shall have accomplished one good thing in my life’ and that he actually did so is a primary plank of the canonical narrative of Limerick 1904.[51]

For example, Keogh and McCarthy claimed that ‘virtually the entire Jewish community in the city joined the exodus’ that the boycott effected, while, according to Jim Kemmy, it precipitated a demographic decline which ‘could not be arrested until eventually only one Jewish family remained in the city’.[52]

However, a highly detailed report on the subject by Hayes dated 12 March 1905 stated that, of 32 Jewish families living in the city in January 1904, only 8 (comprising 49 persons) had left by that time.

Moreover, just 5 (comprising 32 persons) of these families had ‘left directly owing to the agitation, as the breadwinners could no longer obtain employment’. The other 3 had left for private reasons, ‘two having arranged before 1st January 1904, to go to South Africa, and the third because its head (a Rabbi) was no longer needed as Minister’.[53]

This feud had reached explosive proportions the following year in a very public row over the purchase of a Jewish burial ground and the fact that Levin, who led the original congregation, told Raus that he had ‘only 24 families’ in his ‘little flock’ (when the community numbered at least 32, and possibly 35 families) suggests that tensions remained high in mid-1904.[54]

However, according to Hayes, the feud was settled in light of the boycott and, now surplus to community requirements, Velitzkin returned to the UK.[55]

In the final analysis, Limerick 1904 was not a pogrom. In an ‘Irish sense’, however, it was certainly as a close as we came.

Hayes also noted that, of the 26 families who remained in Limerick in March 1905, only 8 were ‘in good circumstances’ and the fact that only 13 of this 26 were still resident in Limerick in 1911 raises the possibility that the boycott claimed more families in the following year.

The canonical narrative’s contention that the reduction in numbers in 1904/05 sounded the Limerick community’s death knell does not bear cursory scrutiny. Des Ryan’s analysis of Limerick census records reveals that 9 other Jewish families made their homes in Limerick between 1901 and 1911, demonstrating that the boycott did not propel the community into irreversible demographic decline: it numbered 121 persons in 1911, compared with, at most, 200 in 1904.[56]

More than half of those resident in 1911 could afford domestic help, and press advertisements and reports, trades directories, and other sources present a vibrant and relatively prosperous Jewish community in subsequent years.

Two, brothers Hyman and Barnett Graff, served as a justice of the peace and magistrate respectively: both had lived through the boycott.[57] The great majority had departed by the time of the 1926 census, which recorded just 33 Jews resident in Limerick city and county.[58] But to attribute this demographic decline to a decades-old boycott is historiographically perverse.

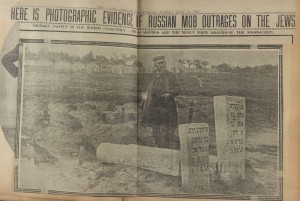

Defining a pogrom

So did Limerick 1904 constitute a pogrom? Responding to Baily eighty years afterwards, Gerald Goldberg remarked that Jews did not ‘need a dictionary to define a pogrom’ and, on his intelligence, Dermot Keogh claimed that the word ‘came immediately to the lips of Limerick’s Jews when they found themselves under attack’.[59] (Goldberg’s father was one of those assaulted, in his case by a man with a shillelagh shouting “I’ll kill those bloody Jews”).[60] Yet Keogh, who argued in his 1998 study that retention of the term ‘pogrom’ was justified in Limerick’s case, has himself since expressed a preference for ‘boycott’.[61]

In the wake of Creagh’s second sermon in January 1904, the Limerick Chronicle referred to ‘uproar which … gives us as a city a Russian like character’.[62] However, the Limerick’s Jewish community would have soon come to realise that they were not facing what Louis Lentin[63] (whose grandparents lived through the events) called ‘a pogrom in the Russian sense’ and the present-day application of the term to Limerick implicitly diminishes the suffering of Jews who endured pogroms such as that perpetrated in Kishinev just 10 months before.[64]

In the final analysis, Limerick 1904 was not a pogrom. In an ‘Irish sense’, however, it was certainly as a close as we came.

References

[1] In 1904, the Arch-Confraternity consisted of two adult divisions, named ‘Monday’ and ‘Tuesday’ for the evenings on which they met each week, and a Boys’ Division which met fortnightly on Wednesday evenings. Mount Saint Alphonsus Monastery (Limerick), Fifty years at Mount Saint Alphonsus, 1853-1903 (Limerick, 1903), pp 57-8

[2] Limerick Leader, 6 Jan. 1904.

[3] Quotations from Creagh’s first sermon are taken from Limerick Leader, 13 Jan. 1904.

[4] This report was published in Limerick Chronicle, 9 Jan. 1904.

[5] Dermot Keogh & Andrew McCarthy, Limerick Boycott 1904: Anti-Semitism in Ireland (Cork, 2005), p. 38.

[6] Freeman’s Journal, 18 Jan. 1904. Levin approached Davitt as he had reported on the Kishinev Pogrom 10 months previously and had just published a book condemning antisemitic persecution in the Russian empire.

[7] Limerick Echo, 19 Jan. 1904.

[8] Limerick Leader, 15 Apr. 1904.

[9] Considine, Departmental minutes, 19 Jan., 9 Apr. 1904, quoted in Keogh & McCarthy, Limerick Boycott, pp 55, 79.

[10] Cormac Ó Gráda, Jewish Ireland in the age of Joyce: a socioeconomic history (Princeton, 2006), p. 192.

[11] Ibid., p. 263, ft. 87.

[12] Limerick Echo, 23 Apr. 1904.

[13] Limerick Leader, 13 Jan. 1904.

[14] Emanuel to Wyndham, 25 Jan. 1904, reproduced in Keogh and McCarthy, Limerick Boycott, p. 81. The London Committee of Deputies of the British Jews was the official representative body of Jewish communities in the UK and is the Board of Deputies of British Jews today.

[15] Limerick Echo, 19 Jan. 1904. Creagh also made clear his belief in the reality of ritual murder in a newspaper interview three weeks later. Northern Whig, 8 Feb. 1904.

[16] Irish Times, 3 Aug. 1984.

[17] Emanuel to Wyndham, 25 Jan. 1904, reproduced in Keogh and McCarthy, Limerick Boycott, p. 81.

[18] For some examples of antisemitic incidents prior to 1904, see Des Ryan, ‘Jewish Limerick from 1790 to 1903’, Old Limerick Journal, 48 (2014), pp 44-51.

[19] https://dib.cambridge.org/viewReadPage.do?articleId=a9310

[20] Irish Times, 27 Apr. 1970.

[21] Criostoir O’Flynn, Beautiful Limerick: the legends and traditions, songs and poems, trials and tribulations of an ancient city (Dublin, 2004), pp 156-224, at p. 158; Des Ryan, ‘Fr Creagh C.S.S.R.: social reformer, 1870-1947’, Old Limerick Journal, 41 (2005), pp 30-2, at p. 32.

[22] Levin to Hayes, 13 Jan. 1904, reproduced in Keogh & McCarthy, Limerick Boycott, p. 40; Limerick Chronicle, 23 Jan. 1904.

[23] Limerick Echo, 23 Jan. 1904. These occasions were the evening of 11 January, in the immediate wake of Creagh’s first sermon, and the morning and afternoon of 18 January, when Jews went out collecting their weekly instalments for the first time since.

[24] The Times, 1 Apr. 1904.

[25] C. H. O’Hara to Hayes, 16 Jan. 1904, reproduced in Keogh & McCarthy, Limerick Boycott, p. 41.

[26] C. H. O’Hara to Hayes, 22 Jan. 1904, quoted in Ibid., p. 56.

[27] Limerick Leader, 27 Jan. 1904; Limerick Chronicle, 28 Jan. 1904.

[28] Northern Whig, 8 Feb. 1904.

[29] The Times, 1 Apr. 1904.

[30] O’Hara to Hayes, 16 Apr. 1904, reproduced in Keogh and McCarthy, Limerick Boycott, p. 111.

[31] Jonathan McGee, ‘The mayoralty and the Jews of Limerick’ in David Lee (ed.), Remembering Limerick: historical essays celebrating the 800th anniversary of Limerick’s first charter granted in 1197 (Limerick, 1997), pp 159-166, at p. 163.

[32] Limerick Leader, 18 Apr. 1904; Limerick Echo, 23 Apr. 1904.

[33] Limerick Echo, 31 May 1904. Adams was County Court Judge of Limerick but lived, for the most part, in London.

[34] Des Ryan, ‘The Jews of Limerick (Part 2)’, Old Limerick Journal, 18 (1985), pp 36-40, at pp 38, 40.

[35] Emanuel to Dudley, 5 Apr. 1904, reproduced in Keogh and McCarthy, Limerick Boycott, p. 88.

[36] Northern Whig, 8 Feb. 1904.

[37] Levin to Hayes, 18 Jan. 1904, reproduced in Keogh and McCarthy, Limerick Boycott, p. 45.

[38] Hayes to Dublin Castle, 12 Mar. 1905, quoted in Keogh and McCarthy, Limerick Boycott, p. 145, ft. 152. Toohey’s exemption is curious as he was also a significant lender.

[39] The Times, 10 Apr. 1904; Irish Times, 17 June 1985.

[40] See, for example, Daily Express, 18 Apr. 1904 & Munster News, 27 Apr. 1904; Ryan, ‘Jews of Limerick, 2’, p. 39.

[41] Pat Feeley, ‘Rabbi Levin of Colooney Street’, Old Limerick Journal, 2 (1980), pp 35-38, at p. 37.

[42] Thomas J Morrissey, Bishop Edward Thomas O’Dwyer of Limerick, 1842-1917 (Dublin, 2003), p. 323.

[43] According to O’Dwyer’s biographer, while he ‘abhorred injustice, boycotting and violence … it is likely that he gave credit to many of the charges of usury against the Jewish traders … He also, presumably, shared to some degree the common European prejudice against the Jews’. Ibid., p. 326.

[44] The Times, 1 Apr. 1904. See also Irish Times, 1 Apr. 1904; Northern Whig, 12 Apr. 1904.

[45] Emanuel to Dudley, 5 Apr. 1904, reproduced in Keogh and McCarthy, Limerick Boycott, pp 87-8.

[46] Levin to Raus, July 1904, quoted in Des Ryan, ‘The Limerick visit of Fr Raus, 1904’, Old Limerick Journal, 25 (1989), pp 158-60, at p. 158. Levin sought an interview with Raus during this visit but received no response.

[47] Moore to O’Hara, 2 Apr. 1904, reproduced in Keogh and McCarthy, Limerick Boycott, p. 94.

[48] O’Hara to Hayes, 7, 13 Apr. 1904, reproduced in Keogh and McCarthy, Limerick Boycott, pp 99, 101.

[49] Dublin Castle report, 13 Mar. 1905, quoted in Keogh and McCarthy, Limerick Boycott, p. 123.

[50] Limerick Leader, 22 Apr. 1904.

[51] Limerick Leader, 20 Apr. 1904.

[52] Keogh and McCarthy, Limerick Boycott, p. 126; Irish Times, 23 Aug. 1984.

[53] Hayes to Dublin Castle, 12 Mar. 1905, quoted in Keogh and McCarthy, Limerick Boycott, pp 123, 145, ft. 152.

[54] Levin to Raus, July 1904, quoted in Ryan, ‘Limerick visit of Fr Raus’, p. 158. On the feud itself see, Des Ryan, ‘Jewish immigrants in Limerick – a divided community’ in Lee (ed.), Remembering Limerick, pp 166-74.

[55] The actual rabbi to the Goldberg faction, Moses Velitskin, left with his family at the same time and, presumably, for this reason, so it would appear that the RIC conflated him and Goldberg in some way.

[56] Ryan, ‘Fr Creagh, social reformer’, p. 32. The widely cited 1911 figure of 122 derives from the fact that Samuel Recusin was entered in two separate households.

[57] Limerick Leader, 9 Feb. 1917.

[58] https://www.cso.ie/en/media/csoie/census/census1926results/volume3/C_11_1926_V3_T8a.pdf This number remained stable until the Second World War.

[59] Irish Times, 13 Aug. 1984; Dermot Keogh, Jews in twentieth-century Ireland: refugees, anti-Semitism and the Holocaust (Cork, 1998), p. 26.

[60] Fanny Goldberg, unpublished memoir, quoted in Keogh and McCarthy, Limerick Boycott, p. 107; Limerick Leader, 22 July 1904.

[61] Keogh, Jews in twentieth-century Ireland, p. 26; Keogh and McCarthy, Limerick Boycott, xv-xvi.

[62] Limerick Chronicle, 23 Jan. 1904.

[63] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Louis_Lentin

[64] Lentin made the remark in his 2006 ‘docudrama’ exploring his grandfather’s life, ‘Grandpa, Speak to me in Russian’ (https://ifiplayer.ie/grandpa-speak-to-me-in-russian/).