‘In the hands of an armed mob’ – The Belfast Riots of 1864

By John Dorney

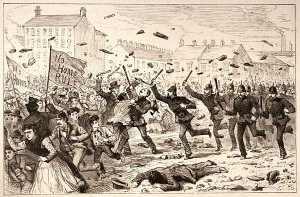

On August 16, 1864, a citizen of Belfast wrote to a friend of his city, ‘The town is in the hands of an armed mob. This is certainly a peculiar state of things … regarding the flourishing capital of the Protestant North. But such is the case and the property nay the very lives of the inhabitants of the citizens are at the mercy of unprincipled freebooters.’

He judged that if ‘the mob had ‘ever held any right principles they have lost sight of them in their thirst for blood and revenge. The authorities are paralysed, are afraid to act boldly and although the military force at their disposal is quite sufficient to quell the disturbances, we have to endure mob law in its worst forms.’[1]

He wrote that ‘Reports are brought in of men shot in the streets like dogs, of bloody affrays between the rival parties, of school houses wrecked, of churches attacked, of shops plundered, of inoffensive persons beaten, of the law set openly at defiance till we are at length until we are inclined to think that we are living among savages. The press ‘give harrowing pictures of the scenes in the hospitals, dead dying and wounded [and] of the surgeons up to their elbows in gore, of the coolness and fury of the mobs.’

At least 11 people were killed and over 300 injured in ten days of rioting in Belfast in August 1864.

In serious rioting in Belfast between Catholic nationalists and Protestant loyalists, from August 9 to 19, 1864, a subsequent inquiry logged 316 injuries and 11 deaths, including 98 cases of gunshot injuries, of which 34 were ‘severe’. There were a further 212 cases of injuries by blunt force, stabbing or slashing. The inquiry concluded that hundreds of shots must have been fired ‘by fellow townsmen on each other with deadly intent’. They estimated the damage to property at over £50,000. [2]

Ultimately it took a force of 700 Irish Constabulary, many of whom were drafted in from the reserve depot in Dublin and 560 British military, including infantry, cavalry and artillery, as well as several thousand special constables, who were hurriedly sworn in, to restore order.[3]

What prompted this ferocious outbreak of inter-communal violence in Belfast, which the Commission of Inquiry described as ‘a fearful tale of vindictiveness and hate’?

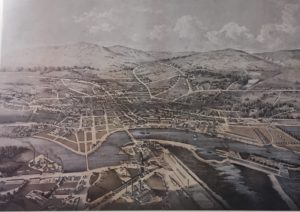

Belfast in 1864

The population of Belfast in 1864 stood at about 140,000, of whom one third were Catholic and two thirds Protestant.[4]

It was also the centre of the industrial revolution in Ireland, with flourishing shipbuilding and linen-spinning industries, amongst others.

These industries had attracted waves of rural migrants to the city, both Catholic and Protestant, and they had brought with them the fierce sectarian strife of rural Ulster to Belfast, which had previously been largely free of such conflict. There were riots throughout the 1850s and rioting in 1857, sparked by anti-Catholic preaching by a Presbyterian cleric named ‘Roaring’ Hugh Hanna, was particularly lethal, with numerous deaths.[5]

As Belfast developed large, adjoining working class neighbourhoods of Catholics and Protestants after the mid 19th century, deadly rioting in the city grew increasingly frequent.

Rioting in Belfast was largely among and between the working class. The Commission of Inquiry into the 1864 riots noted that ‘chief theatre of the disturbances…as on former occasions’ was the interface between the Catholic ‘Pound’ district, today the beginning the Falls Road and Divis Street, and the Protestant Sandy Row neighbourhood. This sectarian frontier, west of the city centre, the Commission stated, was ‘known by evil fame throughout Ireland’ for sectarian violence.[6]

The Commission vividly described working class west Belfast, both Catholic and Protestant: ‘The class of houses throughout is small; in some streets in each district clean and tidy, in others very squalid and miserable.’

They housed, ‘the working population of the town, mechanics and artisans of all different kinds, mill workers and day labourers, with of course in the larger streets, shopkeepers, generally of the inferior kind…Several of the great spinning mills of Belfast are located within or immediately adjoin the two districts, also foundries and other similar establishments largely employing the inhabitants, both young and old ,male and female’.

The symbolic frontier between the Catholic and Protestant working class neighbourhoods was the ‘Boyne Bridge’, a railway bridge on Durham Street. A Constabulary barracks was located on nearby Albert Street, intended to keep the two sides apart. The Irish Constabulary[7] was an all-Ireland armed police force responsible to the Irish Executive in Dublin Castle. In Belfast they were regarded as a fairly neutral force, but there were only 65 constables stationed in the city, not even nearly enough to keep order in the face of widespread disturbances.

Much more partisan were the Belfast Borough Police (also known as the ‘Town Police’), 160 strong, only 5 of whose officers were Catholics and who were under the control of the town council, which itself was controlled by Protestant Conservatives. The Town Police had reportedly acted in a partisan manner in favour of the Protestants during the riots of 1857, and in 1864 the Inquiry commented that ‘Orangeism prevails to a considerable extent among its members’.[8]

Partly, rioting in Belfast reflected economic tensions. Catholic and Protestant workers competed with each other for jobs, with Protestants all but monopolising the better paid shipyard jobs, while the Catholics were more likely to be unskilled labours or ‘navvies’.

But communal violence was also about symbolic communal control of territory in the city and then, as it still is in the twenty first century, conflict was often caused by the attempt to openly display and to parade the symbols of their own communal identity into the ‘territory’ of the other.

The start of the riots

So it was in 1864. The Orange Order the Protestant fraternal and militantly ant-Catholic, organisation founded in 1795, had had its parades effectively banned in 1850 under the Party Procession Act which was brought in after the bloody faction fight between Orangemen and Catholic Ribbonmen at Dolly’s Brae in County Down in 1849, in which at least 30 people were killed.

The Act prohibited ‘marching together in procession in Ireland in a Manner calculated to create and perpetuate Animosities between different Classes of Her Majesty’s Subjects, and to endanger the public Peace’.

In August 1864, however, nationalists from Belfast travelled to Dublin for a mass rally there to honour the memory of Catholic nationalist leader Daniel O’Connell (who had died in 1847), culminating in a parade to lay the foundation stone to a statue to ‘the Liberator’ in Dublin’s main street.

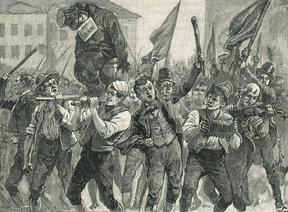

The 1864 riots began when Protestant extremists, angry that Orange Order parades had been banned, attacked Catholic returning from a nationalist rally in Dublin.

Protestants in Belfast and particularly Orangemen, were outraged. Our anonymous letter writer, a Protestant himself, though not an Orangeman, opined, ‘This procession in my opinion was without doubt a party one and even worse’.[9] Green banners, green and white rosettes, repeal[10] scarves, the harp without the Crown, are party emblems as much as Orange flags and orange lilies. And the fact of this array being tolerated in the very seat of the Executive while the Emblems Act[11] was brought into operation against the Orangemen raised a spirit of defiance and naturally annoyed Protestants of all kinds.’

When the Belfast nationalists returned by train to the northern city, they were greeted at the train station by what our letter writer termed, ‘the Sandy Row rabble’, who stoned the nationalists leaving the train and burned an effigy of Daniel O’Connell.

That might have been an end to the affair, but the Protestant extremists proceeded to attempt to march on the Catholic Pound district. Police prevented them from entering the Lower Falls/Divis Street area but the following day loyalists in Sandy Row staged a mock funeral for O’Connell, again marching towards the Catholic district, The Pound, causing Catholic to mass to defend the area, tearing up the street paving stones which were stockpiled for missiles.

This confrontation triggered rioting between Catholics and Protestants all over Belfast, but particularly in the Sandy Row- Pound District in west Belfast and around the city’s dock and shipyards in the east, for over a week.[12]

The disturbances escalate

After the initial disturbances around the mock burial (August 9), the Riot Act was read, meaning that police were authorised to use deadly force to disperse crowds who disobeyed their orders. But the following day violence worsened with stone throwing on both sides.

Catholic churches and lay institutions such as Bankmore Female Penitentiary were attacked by the Protestant mob and Protestant schools were attacked in retaliation by Catholic ‘navvies’, with over 400 children inside, some of whom were injured. Stones were thrown through windows and shots fired by the Catholics.

Our letter writer remarked that ‘Roman Catholic navvies who unfortunately were employed here… walked through the principle part of the town, terrifying the inhabitants, barbarously attacked the Brown Street Schools, where the poor little children were at their lessons; but I need not enter into details. Neither side can boast of the spotless character of its champions.’

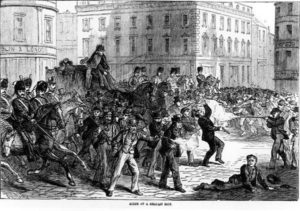

Schools and churches were attacked, gun shops looted and there was a ‘pitched battle at the docks between Catholic and Protestant workers.

Mill workers of both religions were attacked on their way to work. Shots were fired on both sides, particularly in heavy rioting around St Malachi’s Roman Catholic Church, which was attacked by the Protestant mob on August 12 and which the Catholics turned out in force to defend. Several rioters were killed when the constabulary opened fire to prevent ‘the Sandy Row mob’ (the commission’s phrase) from attacking the Pound District at the Boyne Bridge on August 16.

A crowd of Protestant dock and shipyard workers marched from east Belfast that day and broke into gunsmiths on High Street, in the heart of the city’s commercial district, and distributed the firearms to their supporters. They also took picks and shovels and knives from a hardware shop. The Inquiry describes these events as ‘The most astonishing instance of lawless daring ever committed in a civilised community’.

Trains from Dublin were attacked and the passengers beaten, due to a rumour that Catholics from the south had come to aid their co-religionist in the rioting. There was also a ‘pitched battle’ between Protestant ships carpenters and Catholic navvies at the New Dock, which ended with the latter being driven into the shallow of the River Lagan. Our eyewitness described how, ‘The brave carpenters drove them into the slop land and then coolly fired on the unhappy wretches when struggling and sinking in the mud and succeeded in wounding several, some mortally and some dangerously.’

Our letter writer managed to stay out of the way of most of the rioting, which mostly took place in the working class parts of the city; ‘the chief streets are free from annoyance except when the mobs make an occasional irruption’. He remarked that, ‘being neither a soldier nor a special [constable] nor a reporter, I have the fear of being Godfreyed [killed while a bystander][13] before my eyes and seek no hazards. Truly it were an inglorious end to be shot by a Pound Street ruffian or a Harcourt Street butcher’.

He did however witness the looting of gun shops on High Street in the city centre by the Protestant mob; ‘I saw a mob enter a hardware shop on High Street at twelve o’clock noon and seize pitchforks and large knives and after tear down a gunsmith’s shutters and appropriate the firearms. And where were the hussars [cavalry]? Where were the infantry? Where the constabulary? Where the local force? Where the magistrates? An echo answers – where?’

‘Blame they most truly deserve’

The Commission of Inquiry was also highly critical of the forces of order in their report in November of that year.

One problem was political. Belfast was divided by the river Lagan, with most of the city, to the west of it in County Antrim, while the eastern part, including the shipyards in County Down, in another jurisdiction. This hampered coordination of police forces.

In addition since the magistrates who controlled the police were elected from the Protestant dominated town council, there were doubts about their impartiality. As for the military, they appeared to be disoriented in the unfamiliar streets of Belfast, unclear about when and how much force they could use on the rioters. They seem to have managed to attract the opprobrium of both sides.

Many were critical of the authorities, both civil and military, for their failure to put down the rioting.

The letter writer described how ‘The conflicting accounts in the newspapers are amusing and sometimes absurd. The Orange journal accounts the praises of the Orangemen, their forbearance, their courage in defence of home and property, their avoidance of plunder except in the case of arms, the dreadful character of the Pound [Catholic] mobs. The Romish [Catholic] organ denounces the conduct of the Orangemen, asserts the necessity of the Catholic protecting themselves, their premises and their wrongs . And all write in blaming the conduct of our magistrates’

In this at least he letter writer concurred; ‘Blame they most truly deserve. Ere this [i.e. before this] they might know the character of our sons and by exercising a little severity a week ago, much bloodshed and anxiety would have been saved. A cavalry charge would then have effectually dispersed the rioters before the advancing bayonets of the constabulary would’.

The military searched the Sandy Row and Pound districts for arms, finding 21 weapons. However, the Inquiry judged this to be ‘very ineffectual’ given the number of weapons by then in circulation in the city owing to the looting of the gun shops.

Despite the now very considerable military presence there was still a final round of violence. On August 18 fighting broke out when rival funeral parties of those already killed in the rioting collided. The last fatality, a shooting, occurred on August 19. Thereafter, following ten days of violence, the riots finally petered out and calm was mostly restored to the streets of Belfast.

Aftermath: disbanding the Belfast Police

The most lasting legacy of the riots, apart from the loss of life and damage to property, was the disbandment of the Belfast Borough Police, whose conduct in the rioting was heavily criticised by the Commission of Inquiry.

They were replaced as guardians of order in the northern city by the Irish Constabulary, who were under the control, not of the town council, but of the British administration in Ireland, based in Dublin Castle.

Moreover, many of their rank and file were Catholics recruited in the south of Ireland and their deployment in Belfast outraged many Orangemen and other loyalists.

After the 1864 riots the Belfast Borough Police, who had been judged to be partisan, were disbanded and replaced by the Irish Constabulary.

According to Mark Radford: ‘The Belfast News Letter referred to the ‘green badge of disgrace’ and prisoners in custody cursed the Belfast RIC for being, ‘a Popish force, a bloody lot of Fenians [and] Popish brats’ in the mistaken belief, perhaps, that the Belfast force consisted solely of Catholic policemen.’

In riots to come in Belfast, notably the anti-Home Rule disturbances of 1886, the Constabulary and the Protestant extremists would have a most adversarial relationship.

Sadly many of the patterns of violence notable in the disturbances of 1864 – the initial clash over a disputed parade, followed by prolonged violence around contested urban territory, remained familiar throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries and even into the twenty first.

As for our anonymous letter writer, he displayed a familiar Belfast stoicism, writing that he smiled when he received letters worried about his safety. He concluded with a quotation assuring his concerned friends in Britain that he was safe, and the rioting had left him untouched; “I think it necessary to quiet you the solicitude which you undoubtedly feel by telling you that our calamities and terror are now at an end.”

In the short term at least, this was true. But rioting in Belfast was very far from being consigned to history after the disturbances of August 1864.

References and notes

[1] This, unsigned, letter was supplied to me by David Williams, who writes: ‘This came from my Great Uncle James Hunter Tate’s (born 1884) house who lived in Helen’s Bay’. Digital copies of the letter can be made available to readers on request.

[2] Report of Commission of Inquiry into 1864 Belfast Riots, online here

[3] Commission of Inquiry, 1864, also, Sean Farrell, Rituals and Riots: Sectarian Violence and Political Culture in Ulster, 1784-1886, p.160

[4] Commission of Inquiry 1864

[5] Joe Lee, The Modernisation of Irish Society 1848-1918, p.51. For an overview see Belfast Riots: a Short History.

[6] Commission of Inquiry 1864

[7] Not yet renamed ‘Royal’ that would come in 1867, for their role in putting down the Fenian rebellion of that year.

[8] Commission of Inquiry 1864

[9]‘Party’ here means divisive, probably sectarian in modern usage.

[10]O’Connell led a movement for ‘Repeal of the Union’

[11] This refers to the Party Procession Act of 1850 which was brought in after the bloody faction fight between Orangemen and Catholics at Dolly’s Brae in 1849. The Act effectively banned Orange parades.

[12] Sean Farrell, Rituals and Riots: Sectarian Violence and Political Culture in Ulster, 1784-1886, p.160-161, Commission of Inquiry1864

[13] This is in reference to a story, apparently well know at the time of Michael Godfrey of the bank of England who ill-advisedly went into the front line to watch the siege of Namur in 1695 and had his head taken off by a cannonball in front of King William I