The Illies and its environs in the 19th Century

Gearóid Mac Lochlainn on life in ‘Illies’ area of north Donegal in the 19th century.

The Illies is a rural area in Donegal’s Inishowen Peninsula. Located north of Derry city, Inishowen is almost the most northerly tip of Ireland. By the 19th century it was a society sharply divided between landlords and their tenants.

Early descriptions

English military commander Henry Dowcra’s description of Inishowen at the beginning of the 17th century shows the peninsula to have been well populated along the coastal lowlands in contrast to the interior which was stated to be “all high and waste mountain, good for feeding cows in summer only but all waste, desolate and uninhabited”.(1)

The predominant settlement pattern was of small villages of farm houses (clachans) whose people farmed the surrounding land in partnership on an openfield system and grew mainly oats, barley and flax. As fields were not enclosed transhumance was practiced whereby livestock, which was the main wealth of the people, was driven to mountain pastures during the growing season.

The English who established a presence in Inishowen in 1600, reported that the Illies area was mostly uninhabited, except for summer pasture.

Inland mountain pastures often belonged to coastal townlands and hence we have the Mintiaghs known as the “Barr of Inch”, Meendacalliagh as the “Barr of Luddan” and Meenyanly as the Barr of Muff (“Barr” being the Irish for “top”).

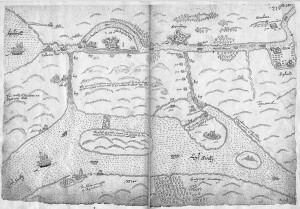

The Illies at this period was such a summer pasture and was totally uninhabited. Both Pender´s Census of 1659 and The Hearth Money Roll of 1665 show that the Crana Valley was inhabited only up to Connagh-Kinnagoe. The situation had not changed very much by 1770 when Crowe´s maps of the Chichester estate show that there were no roads nor houses apart from a herd´s enclosure where Kelly´s house at the “Head of the River” now stands.(2)

There were only a few tracks crossing the area as most transport was by pack-horse. However by the time the Tithes Roll(1829) and the first Ordnance Survey maps were produced in the 1830´s things had changed dramatically. A road had by then been driven through the Illies and the ladder farms established similar to what they were at the beginning of the 20th century although the field patterns were not as yet fully developed.

It would seem that the Illies along with Evishabreedy was summer mountain grazing for the Mac Lochlainn, whose territory lay along the Foyle around Redcastle and Whitecastle, and as such at the plantation of Inishowen was confiscated and granted to Chichester who then leased them to George Carey along with the other townlands of the territory.(3) The dispossessed families from the more fertile Foyleside townlands had to move to less fertile lands and pay a rent to the planters.

Landlords and tenants

Always strapped for cash to fuel their lifestyle the Chichester custom of demanding an initial heavy down-payment and a relatively low yearly rent for lease of properties prevented smaller farmers from bidding for those leases so that middlemen (often Derry business people) who were able to pay the sums demanded got control of the land and then sublet the small farms at ever higher rents.(4) In some places there was a second layer of middlemen and resulting rack renting caused great hardship for many farmers.

Even when smaller holders could afford the leases a difference was made between Catholics whose leases ran to 31 years and Protestants who got 61 year leases. The tenants had no encouragement to make improvements on their farms as such would only lead to a rise in rent. Bog reclamation did not take place because the landlord kept for himself the right to rent out moor for turf cutting. (5) By 1800 most small farmers were tenants-at-will and rents rose steeply, often doubling, in the next 15 years, due to the high prices being offered for barley to supply the demands of illicit distillation.

By 1800 most small farmers were tenants-at-will and rents rose steeply, often doubling, in the next 15 years,

The descendents of George Carey lived isolated from their Irish tenants, the fruits of whose labours they enjoyed to the full, socialising and marrying within the small circle of English-descended families.

They were no less fond of the good life than their overlords, the Chichesters, and so by the end of the 18th century their expenditures far outstripped their income with the result that they were obliged to mortgage parts of their estate and eventually put the whole up for sale in the Court of Chancery. (6) The Illies and Evishabreedy remained in possession of the Careys until at least 1819 when they are mentioned in an indenture of sale to Simon Rose of that year. (7) By the time of Griffith’s Valuation (1857) they had both passed into the possession of George Harvey.

The Batesons

The Batesons were a Lancaster family who came to northern Ireland in the 18th century. Richard Bateson settled in Derry where he married his second wife, Elizabeth Harvey. Her brother, David, was a linen merchant involved in transatlantic trade who operated from Cheapside, London, catering for linen producers in the Derry area. (8)

The Irish Society was able to proclaim in 1748, based on the affidavits of this David and two others reared in Derry but now working in London, that not one papist lived within the Derry city walls after they were ordered to leave by the corporation before the 1st May 1745. (9)

Richard´s son Robert probably worked with his uncle David as he lived just round the corner from him and when the latter died in 1788 he left a large fortune to Robert on condition that he take the extra surname “Harvey” (a not uncommon practice where a testator would die without a male heir and wished his family name to continue). This he did in September of the same year by royal licence. (10)

The Batesons were the principle land-owning family in the Illies in the 1800s

The now Robert Bateson Harvey, with his new found wealth, bought a title (Baronet of Killoquin) and several estates in England, including Langley Park, Buckinghamshire, which would become the family home. (11) He also began to buy up leases in Inishowen so that by the time of his death in 1825 he had acquired lands in Clonca, Muff, Desertegny, Clonmany and Lr.Fahan (Evishabreedy and The Illies by indenture of 1819 modified in 1830 fronted by Dublin law firms of Rose and later Hyndman (7).(11)

Although he never married Robert had at least four sons and three daughters. When he died his title passed to his nephew by his half brother as all his own children were illegitimate but they did however inherit his properties. Curiously although the eldest son, Robert, and descendents who inherited Langley Park continued to use the double barrelled name, though often reducing Bateson to its initial, the others styled themselves simply as “Harvey”.

The second son, William Henry, had entered the church and after serving as curate in various parishes was in 1821 appointed rector of Crowcombe, Somerset, where the family had a large estate. (12) After his father’s death he inherited the Inishowen property and so in 1827 he resigned his rectorship (13) and moved to Desertegny where he built a large residence known as Linsfort House at a cost of £3000 (forty years later a house in the Illies with its accompanying outhouses could be built for under £30).

He also had a school built in Linsfort (14) while his cousin, Robert Bateson, 1st Baronet of Belvoir and Conservative MP for Derry, who strongly disapproved of Catholic Emancipation, crossed swords with the O’Connells (Daniel and son) on the question of education of Catholics which he thought should be in the hands of Protestants through the Kildare Street Society.(15)

This family was forever swimming against the tide of history. His son, an ultra conservative MP was absolutely opposed to electoral reform saying it would lead to “emasculation of the aristocracy” and thundered in Parliament “This new born sympathy for the workingman had been begotten by a lust for power, suckled by the unctuous pap of peripatetic stump orators, and dry-nursed by the insolent threats and swaggering bluster of domineering agitators” (16)

The Batesons were ultras Conservatives – opposed to Catholic Emancipation and extension of the franchise.

In the same year (1831) the Rev. William applied on two occasions to have Cornelius and Denis Kelly along with six others evicted from some lands but both times it was not decreed. (17) In 1810 his father had bought the 6 coastal townlands of Clonmany(18) so that Harvey held all the land, with the exception of Desertegny Glebe, on the eastern shore of Lough Swilly from Porthaw Glen, beside Buncrana, to Tullagh Bay and the salmon fishing of this whole coast was let in 1834 to a Mr. Halliday, a Scotsman resident in Derry, for the sum of £30 annually.(14)

However not long afterwards William became ill and moved back to England into the care of his younger brother at whose residence in Cheltenham he died in 1840 after a prolonged illness.(19)

Brother George who now inherited the property had no intention of living in Ireland. In 1844 his cousin, Thomas Douglas, brother of Sir Robert Bateson, 2nd Baronet of Killoquin who had inherited his father’s title, was acting as estate agent and living in Linsfort House. He was one of the witnesses who gave evidence to the Devon Commission on the state of agriculture in the Buncrana area.

Shortly afterwards he took up employment as agent for the Templetown Estate in Castleblayney where his harshness led to his murder in 1851. He had earlier evicted 34 families leaving 222 people sitting without shelter on the roadside. This was not the first time that he had run foul of his tenants because 10 years previously a plot to kill him had been uncovered in Co. Donegal.(20) He admitted in his evidence to the Devon Commission that the tenants complained of exorbitant rents.

After his departure from Inishowen George handed over the management of his properties to the ruthless estate agent, John Millar, who took up residence in Linsfort House. This man carried out George’s bidding with the utmost cruelty and an example of his work appeared in the Derry papers of 1849 when Nancy Mc Laughlin was evicted from her home in Leophin.

Evictions

Evictions were commonplace but the fact that Millar backed his bailiffs in their obviously outrageous treatment of the family and went so far as to haul them before the courts considering the trauma they already suffered says much about the character of the man. He would brook no resistance to his will and through this court case made that fact public.(21)

Evictions were common in the late 19th century.

George held 25593 acres in Inishowen, making him the largest landholder in the peninsula and it is he who appears in Griffith´s Valuation as the immediate lessor of many of the townlands of the Crana valley including the Illies. He died in 1881 leaving his property to his nephew, another Robert Bateson Harvey, Baronet of Langley Park.(22)

The new landholder would be another absentee landlord but just as demanding of his tenants as his predecessors. In 1882 before the circuit court sitting in Carndonagh he presented applications for the eviction of 12 tenants and in 1887 he set John Millar to work, reported by The Irish News as follows:- (23)

“On January 14 several evictions were carried out on the estate of R.B. Harvey by the under sheriff of Donegal accompanying whom were 7 cars of police under the direction of Mr. Harvey R.M. and M. Winder D.I.

These evictions were quite unexpected as but the previous week the tenants waited on the agent seeking an abatement and though they got no great encouragement they expected he would communicate with the landlord, who is credited with being a fair man, and thus secure for them reasonable terms.

The sheriff and party were in the village of Clonmany at an early hour and ready to begin operations shortly after 9 o´clock a.m. The first house visited was that of widow Ellen Doherty, Tullagh. The occupants of the house consist of her and daughter, her only son having gone to America about a year ago, being unable to live on the farm which is exceptionally high rented. The second person who was fated to go through the trying ordeal of being turned out of the home of his forefathers was George Mc Laughlin, Urrismenagh. The family numbers 7 persons and though the poor man offered to pay 3 half year´s rent it was rejected by the agent.

The bailiffs, who met no resistance, soon cleared out the house and it was a sad sight to see the poor fellow sitting by the roadside with his family around him, the big tears rolling down his cheeks, whilst he looked at the agent nailing up the door with his own hands. The third family visited consisted of 2 unmarried girls, one of whom is extremely delicate. These tried to make a settlement offering the agent all they had in the world, as they said, but to no effect; the bailiffs were ordered to do their work which did not delay them long. Harry Mc Daid’s turn came next.

This man ought to be quite familiar with the sheriff and party having received a visit from them on 2 previous occasions. He has a wife and 6 young children and they all lived in a little house of about 10 feet square right up at the foot of Baughter. The operation of clearing out the house was more unpleasant than laborious. Small and uncomfortable, however, as the place was the poor fellow would not be allowed to remain there though having paid twice over in rent the value of the rood of stony ground which he had made out of the mountain side; not a man in the world would give the law expenses for the holding.

The fifth case was perhaps the most heartrending of all. Widow Grace Gibbons is the tenant before whose house the word of command is given to the little army to halt. The particulars of this woman’s case furnish an instance of the unfortunate occurrences that have made it impossible for landlord and tenant to live in harmony in this country. This woman lost her husband by his efforts to pay the rent. Returning home from a mission of this nature a most tempestuous evening came on and the poor man was blown off the road into a large pool from which he was extricated with difficulty but died soon afterwards from the effects of exposure. The woman has 5 little children, all girls, and is most destitute.

So apparent were the hardships of her case that one of the officers in command of the police, moved by pity, gave her all the money he had about him. Mr. Millar has been exceptionally sharp with this unfortunate woman. He attempted on a former occasion to evict her without a decree and the sheriff was actually about to throw out the effects when he discovered his error. Philip Mc Laughlin was next evicted. The man lives by himself and eviction won’t press so heavy on him. This finished the day’s work. All passed over quietly though the evictions were witnessed by fully 500 people filled with indignation at seeing their neighbours so heartlessly cast out of their homes.”

When I was a small boy I used to spend all the time that I was allowed in the Illies and I remember one evening on the street in front of the house trying to squeeze the last drops of sunlight out of an autumn day my grandmother saying to me “ a heskey, look yer al wetshod. Come in out a the caul afore John Millar gets ye”. Of course I had no idea who John Millar was nor do I think had she but it shows how terror of the man lingered on in the minds of the people long after he had departed the scene.

Robert died later that year (1887) and his second son Major Charles Bateson Harvey now inherited the Inishowen property. He married Catherine Maria Lascelles in 1891 but he was killed in 1900 in the Boer War. Three years later the Irish Land Act was passed and the Harvey estate was sold in her married name although individual farms were being sold off at least 6 years earlier.

Ribbonmen

It should come as no surprise that the people of Inishowen, as in the rest of Ireland, took measures to protect themselves from the abuses of these landlords and so secret societies were formed to fight back known as Ribbonmen or Molly Maguires.

Some secret societies set up to resist landlords prey just as heavily on the local population.

However as often happens with such organizations control falls into the hands of local thugs who prey on tenants rather than protect them and such was the case with the group in this area known as the Cleenagh Men because as the local doggerel says they held their meetings “behind a ditch in Cleenagh”. Many stories of their exploits are recounted and it was said that if a man brought a young heifer worth £5 to a fair in Buncrana and was offered £3 by one of these thugs he would be well advised to accept it for fear of what might happen to himself or his family otherwise.

In 1896 the position of work mistress in Kinnego School became vacant. Cassie Blieu from Ballymagan applied and was appointed over the daughter of one of the gang members. Obviously this did not go down well and a campaign of terror was organised against parents of the pupils with the aim of getting them to boycott the school.

When this did not succeed four masked ruffians broke into the Blieu home one dark night and unmercifully beat the family with stout sticks causing serious injury to the father and sons and then before leaving smashed the windows and doors. The eldest son, Charlie, never recovered and suffered a total mental breakdown. He had recurring panic attacks when he showed signs of extreme terror and on occasions became violent.

The family sought to have him committed to an asylum but out of pity did not proceed with their intent. On Sunday 14th. March 1897 while his two sisters were at Mass Charlie was seized with a fit of terror and in his insanity attacked with a beetle the members of the family in the house at that time killing his father, Robert, and rendering unconscious his mother, his brother Willie, who had been sick in bed for some time past, and a little niece, Rose Callaghan, who was eight years old. As he struck his victims Charlie uttered the words “God bless you”. He then tried to cut his own throat. Later when restrained but still in a dazed state, he declared “that’s the rear of the Cleenagh men”.

Charlie was committed to Derry Goal and at the Donegal Assizes held on Friday 16 July 1897 the medical officer for that institution declared that “the prisoner was admitted on the 15 March. He was labouring under acute mania. He remained in gaol and under my notice for two months. On the 12 May he was transferred to the Lunatic Asylum. During that time he continued in the same condition. I saw the prisoner that morning and he was still in the same state – quite unfit to plead or know what was going on.” The jury found that the prisoner was not of sound mind or capable of pleading. He would be detained in strict custody for the rest of his life. (24)

The Foyle Disaster

This was not the only tragedy to befall the Crana area in the 19th century. In 1865 news of the Foyle Disaster stunned the whole area. The disaster occurred on Saturday 16th September 1865 at 3:25 P.M. on Lough Foyle between Whitecastle and Quigley’s Point, as a result of the collision between the steamers Garland and Falcon. The former left Derry at about 2:00 P.M. with a cargo of livestock and some 50 passengers on her way to Glasgow. It was a clear day with calm water.

In 1865 17 men drowned aboard a boat on Lough Foyle on its way to Glasgow.

There was plenty of sea room and yet she struck the Falcon on the port bow with subsequent loss of life. The latter was on her way to Derry crowded with Irish reapers returning from the Scotch harvest. After the crash the two vessels separated and it was observed that a number of reapers were in the water. It seems that in their panic many of them rushed for the lifeboats fearing that the Falcon was about to sink.

Such was the number that scrambled aboard that the ropes holding the lifeboats broke throwing the men into the water. Although some were rescued many drowned and by Saturday 23rd September 17 bodies had been recovered, among whom were the following five men from the Buncrana area:- 1) John Mc Daid from Tirk, who went to Scotland a week earlier to buy sheep. 2) James O’Donnell from Tonduff. 3) Patrick Doherty from Tullydish. 4) Bernard Bradley from the Illies. 5) James Mc Laughlin from the Illies. (25)

‘Very great injustice’

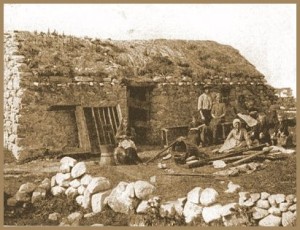

As the 19th century progressed the whole appearance of the Crana valley changed as it did elsewhere. The Irish villages were gradually broken up by the landlords through evictions and the houses splattered over the countryside to create the landscape that is now considered typically Irish.

As the Rev. E. Mc Ginn (later bishop Mc Ginn) explained to the Devon Commission “I know from the very great injustice done to many individuals in the district by those persons not understanding sufficiently how to cut up the land. They cut up the land and gave the best of it to two or three individuals, and banished the rest up the mountain.”

Thomas Douglas Bateson, in his submission to the Commission says “The whole barony was in rundale not long ago. I subdivided the estate which fell out of lease into farms proportioned to the rent which the rundale tenants formerly paid, locating the stronger families up towards the hills”.

Socially the changes were deep also. The Irish language disappeared. In the 1901 census only 19 people in the Illies Electoral Division stated that they could speak Irish. At least three of my great grandfathers could speak Irish and socialised with neighbours and friends of their own age group in that language yet none of them registered that ability in the census. At the time of the plantation Gaelic Intellectuals recognised that what was intended was the creation of a “Sacsa nua darb ainm Éire” [‘a new England called Ireland’] and at the end of the 19th century this had finally been achieved.(26)

Notes.

1 Calendar of State Papers – Sir Henry Dockwra to Sir Robert Cecil 19th Dec. 1600 section 85 P.94

2 PRONI – Crowe´s maps of Chichester estate 1767-70 Upper Illies – D.835/1/1/103; Evisbreed – D835/1/2/104; Middle and Lower Illies – D835/1/1/93

3 List of those holding land under Sir Arthur Chichester in 1622 as it appears in “That Audacious Traitor” by Brian Bonner. P. 221

4 Harvey town lands of Clonmany sublet first to Mrs. Merrick ( O. S. Memoirs) and later to Minchin Lloyd (Griffith’s Valuation)

5 Information extracted: a)from the Devon Commission April 1844 submissions by Rev. E Mc Ginn No. 166 and Mr Samuel Alexander No. 167; and b)the Ordnance Survey Memoirs for parishes of Clonmany, Desestegney, Donagh and Mintiaghs.

6 Joyce Cary Remembered: in letters and interviews by his family and others. PP 6 and 7.

7 PRONI The Cary Papers. D2649/5/3.

8 Irish and Scottish Mercantile Networks in Europe and Oversees in the 17th and 18th Centuries by David Dickson, Jan Parmentier and Jane H Ohlmeyer. PP 276 -279.

9 The Hillhouse family of Irvine, Scotland and Dunboe/Aghanloo c.1600-1750. P 9, note 63.

10 Peerage & baronetage of Great Britain & Ireland. P 70

11 The National Archives (England) Langley Park estate and other estates of the Harvey Family. D31/F/1

12 New Monthly Magazine 1821, vol. 3, Ecclesiastical Promotions, P 365.

13 On line: “View Career Model Record for Harvey, William Henry.

14 Ordnance Survey Memoirs. Parish of Desertegney.

15 The Parliamentary Debates July 14th. 1831

16 New York Times, 21st June 1866, Web Site “Eviction in Ireland” www.maggieblanck.com

17 Enquiry into the condition of the poorer classes in Ireland (Civil Bill ejectments P256 Nos. 560 and 583.

18 1814 Statistical Account – Parish of Clonmany. By Rev. F.L. Molloy

19 National Archives (England) Harvey Documents. Personal Letters to Robert Harvey from George Harvey and others about his brother’s Illness, 1838-40. D140/90

20 ‘The Murder of Thomas Douglas Bateson’ by Michael Mc Mahon

21 The Derry Journal – Buncrana Petty Sessions, Thursday July 5 1849

22 The London Gazette, 11th February 1881

23 Internet> Papers Past – New Zealand Tablet- 1887 Irish News> Evictions in Donegal.

24 The Derry papers (Journal and Standard) 15th and 17th March and 19th July 1897.

25 The Derry papers (Journal and Standard) 20th and 23rd September 1865.

26 “Sacsa nua darb ainm Éire” (A new England called Éire) is taken from Fearflatha Ó Gnimh´s 17th century poem “Mo Thruaighe mar táid Gaoidhil” (Pitiful the Plight of the Gael) in Measgra Dánta, Miscellaneous Irish Poems, Part 1, T.F. O´Rahilly, editor, Cork University Press/Educational Company of Ireland, 1927.