‘We must forgive but we won’t forget’ – The Treaty debates in the border counties.

How was the Anglo-Irish Treaty received in the counties it made a frontier zone? By John Dorney.

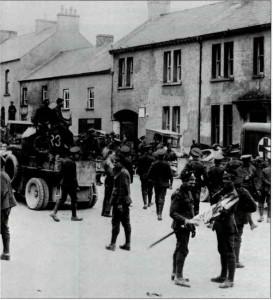

If you lived in the strip of Ireland from Dundalk to Leitrim in late 1921, there was much to be worried about. It was a period of interregnum, after the cessation of the Irish War of Independence, and pending a political settlement that was being negotiated in London. As of 1920 the British government had drawn a new border at the north of your county line, creating a new frontier between the territories it called Southern Ireland and Northern Ireland.

Nationalists on the southern rim of the new border zone were scornful of the new Northern State. The local nationalist newspaper opined that the Northern Parliament was, ‘A discredit to a third rate creamery’. With ‘overpaid ministers’, and a ‘huge police force, one policeman for every 10 inhabitants’[1].

With a new border separating neighbouring villages, rival militias, a tentative ceasefire and simmering social problems, there was much trepidation in the region in late 1921.

But as of late 1921, executive and policing powers had been devolved to Northern Ireland from London. It began to look as if Northern Ireland was there to stay. Two rival militias now patrolled either side of the new border, the Irish Republican Army (IRA) guerrillas to the south and Ulster Special Constabulary (USC or ‘Specials’) to the north.

The IRA had been in an uneasy truce since July 1921 with British troops and Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) police. Many were fearful of a return to war. And rival police forces, the RIC and the Irish Republican Police (IRP – an adjunct to the IRA) competed to impose their own order. In November, for instance, the Republican Police arrested several youths for drunkenness at Carrickmacross fair, only for the RIC to arrest the IRP officers for false imprisonment. At a fair at Clones both RIC and IRP investigated a stolen horse. In the event, the IRP retrieved the horse, while the RIC arrested the alleged thief.[2]

The result of this zeal for competitive law enforcement was not more security but, with no effective, impartial police, a breakdown of law and order. Crime such as burglaries, land seizures and cattle theft spiraled.

And on the land, agitation had sprung up across the region in late 1921. This was a poor rural region and though many farmers had taken the opportunity afforded by British land reform to buy out their landlords since 1908, many families were still paying rent to old-style big landlords (often of the Anglo-Irish gentry class and often absentee). A rent strike by tenants started on November 25th in the Portland estate in County Monaghan, but rapidly spread across the whole of the north midlands by late December, demanding a 50% reduction in rent and the compulsory purchase of landlords’ estates and ownership right to be given to tenants.[3]

So in the border counties, people waited nervously for what came out of the London negotiations. Who would form the new state in two thirds of Ireland? Would that state be independent? Would the partition of Ireland be permanent? No one as yet knew.

On December 6 1922, the Irish negotiating team in London, headed by Michael Collins and Arthur Griffith, signed the Anglo-Irish Treaty. The Treaty created in the southern 26 counties of Ireland a self-governing dominion under the British Crown, to be known as the Irish Free State. Northern Ireland (the north eastern 6 counties) would be given a year to decide if it would join it.

Over the following month, the Treaty was heatedly debated in the republican parliament, the Dáil, in Dublin, where Eamon de Valera, the President of the Irish Republic declared in 1919, rejected the settlement his negotiators had brought back from London. But the Treaty was also debated fiercely at local level, in county and town councils, trade and farmers unions and other assemblies right across Ireland. Nowhere was the impact of the Treaty more obvious in the counties which it would make a frontier zone.

Reactions to the Treaty

For some republicans on the Northern side of the border there was naturally anger at what appeared to be a meek acceptance of partition. Patrick Casey, an IRA member from Newry, had been preparing, as he put it, ‘for the resumption of hostilities’ and was staying in the home of sympathetic schoolmaster, McKevitt, near Banbridge as he was visiting the local IRA units.

‘When we awoke the [Irish] ‘Independent’ [newspaper] had arrived and contained all details of the terms and signing of the Treaty. I remember well McKevitt, senior, saying that the terms were not a settlement and would lead to bloodshed. How true, in fact, were his words to become in the matter of a few months!’[4]

But more broadly, especially on the southern side of the border, the initial reaction to the Treaty seems to have been one of relief. After all there would be an Irish state there, with an Irish army and police. British forces would evacuate the territory of the Free State. All 3,600 Irish republican internees would be freed.

Many republicans, especially on the Northern side of the border felt let down by the Treaty, but generally the response was one of relief.

The release of local prisoners (most of whom had been held in an internment camp at Ballykinlar, County Down) seems to have been a powerful local selling point for the Treaty. They were given heroes’ welcomes on their return to their home towns and villages in the next two weeks.

At Clones, county Monaghan, the prisoners marched through the streets accompanied by a Pipe band, the Ancient Order of Hibernians band, as well the IRA, Cumann na mBan and Sinn Fein contingents to a rally where they were addressed by a priest, Father O’Daly. At Cavan town the prisoners were feted with a torch lit parade. The local press reported, ‘Hearty handshakes’ for the 36 Cavan prisoners welcomed home, who ‘looked remarkably fit’, considering their experiences.[5]

‘It would be criminal not to accept it’ – Support for the Treaty

In the IRA, several important local leaders in the border area, notably Sean MacEoin of north Longford, Eoin O’Duffy of Monaghan and Paul Galligan of Cavan publicly came out in favour of the Treaty.

Many, like O’Duffy, expressed serious reservations in private about whether the Treaty would solidify the new border, but loyalty to IRA GHQ in Dublin and in particular to Michael Collins ensured their assent for the Treaty.

O’Duffy was in Dublin when the Treaty was published and allegedly told IRA Chief of Staff Richard Mulcahy, ‘The Army won’t stand for this Dick’. Mulcahy responded, ‘wait until you see Collins’, who apparently talked him around[6].

Frank Aiken, the commander of the IRA Fourth Northern Division in the area of north Louth, South Down and South Armagh, that now spanned both sides of the border, was against the acceptance of partition but was persuaded not to oppose the Treaty in public by Collins, who assured him that not only was partition temporary but the new Dublin government would support IRA military actions across the border.[7]

Pro-Treaty nationalists presented the Treaty merely as common sense, its defects only temporary

On the political front late December and early January saw a concerted campaign by pro-Treaty supporters in the area to build support for the settlement. A host of civil society organisation passed motions, overwhelmingly in favour of the Treaty. Paul Galligan, TD for West Cavan as well as IRA commander, received a host of telegrams and letters from public bodies and parish councils in Cavan in the weeks leading up to the Dáil vote on the Treaty urging him to ratify it.

The Cavan town Urban District Council for example wrote, of its, ‘high appreciation of the terms of the Treaty’ and urged all TDs, ‘for the sake of our country to bury their differences and stand with Arthur Griffith and Sean McKeon [MacEoin] for the ratification of the Treaty’.

The Swanlibar Sinn Fein Club, ‘trusts that the Treaty shall lead to the establishment of a Republic at no distant date” and urged ratification, “to prevent the appalling consequences of a split’. The Belturbet District Council thought that, ‘99 per cent of the people call for Ratification’.[8]

Seamus MacDiarmada, a Cavan IRA intelligence officer remembered,

‘Every public body in Cavan urged its acceptance, members who had not attended in years turned up to support it. My proposition against it [the Treaty] caused much the same reaction as an atomic blast would today [1952] in Cavan town – voting 15 for 3 against’.[9]

At the Bawnboy Poor Law Guardians meeting a Mr McBarron declared, ‘I don’t believe there is one in my district opposed to the Treaty’. They resolved: ‘though a fraction short of Republican aspirations, it gives us the freedom that no nationalist leader ever expected… ‘Without any more bloodshed, time and proper understanding between Ireland and England will put these things right’.[10]

Almost every public body in the border region voted to endorse the Treaty.

Pro-Treaty nationalists presented the Treaty merely as common sense, its defects only temporary. One Joe McCarthy a Louth farmer, thought, ‘It gives us everything except Ulster and wise government and gentle economic pressures will induce Ulster to come in’.

It was, moreover, in a phrase repeated constantly, ‘the will of the people’. At the Monaghan Sinn Fein meeting, the Chair, a Catholic priest, Father MacNamee argued, ‘It is possible that the majority of the representatives of the people are against the Treaty but the majority of people are in favour of ratification’. The motion proposed by another priest, Reverend Murphy, seconded by IRA leader Eoin O’Duffy resolved, ‘it would be criminal folly not to accept the Treaty’.[11]

And there remained a sizable minority in the border area, mostly Protestant, many of whom were successful farmers and businessmen, who were relieved that the connection with the British Empire was not going to be severed fully.

At the meeting of the Louth Farmers’ Union in Dundalk for instance, William Russell, who said he represented the ‘large commercial community’, argued that he was ‘proud to be associated with the British Empire’ and that he opposed complete separation as a, ‘Republic would mean we would be foreigners in the Empire’. A Major Barrow (‘just back from India’) told the meeting that, ‘remaining in the Empire gave Ireland all the advantages of belonging to a big firm’. Ratification, he argued, was necessary or they would be ‘fighting a much bigger man’.[12]

‘Freedom was won by a sacrifice of lives’ – Anti-Treaty voices

Anti-Treaty Republicans were in a distinct minority in the region. Their view, articulated in the newspaper, An Phoblacht [the Republic] was that; the ‘will of the people’, could not be freely expressed under a British threat of force; ‘We shall labour to unite the Irish People temporarily disunited under duress and the temptation of an easy peace.’[13]

In their world there was no room for compromise. The Irish Republic had been declared by the Irish people, fought for and there was no good reason to throw it away for the compromises inherent in the Treaty. They would proceed, ‘upon the only basis upon which unity is possible; loyalty to the Irish Republic, established once and for all in 1919’. [14]

Some swallowed their pride. Leitrim County Council reluctantly endorsed the Treaty though it acknowledged that, ‘The Treaty is not popular and opinion is divided. ‘This is not what Sean MacDiarmada [Leitrim born IRB leader, executed in 1916] gave his life for’.

Anti-Treaty Republicans knew they were a minority in the region but insisted the people were being scared into supporting the Treaty.

In meeting after meeting along the border however, the anti-Treaty republicans simply asserted that rejecting the Treaty was a point of principle and that no other argument was required.

In the Cavan County Council Meeting of January 1, 1922, a Mr Fitzsimons proposed a motion to endorse the Treaty, arguing that, ‘Whilst it does not realise all the hopes of the Irish nation it safeguards the best interests of the Gaelic nation. Also there is no alternative”.

The following exchange gives a good indication of the unsophisticated but quite determined outlook of the anti-Treaty Republicans. Mr Boylan responded to Fitzsimons with a counter-motion;

Mr Boylan, ‘As republicans we do not approve of the Treaty.”

Fitzsimons and several others responded with a reiteration of the pro-Treaty case.

Fitzsimons; ‘I am as convinced a republican today as at any time over the last 4 or 5 years. The Treaty is not a final settlement. I swore an oath to the Irish Republic but have no qualms about transferring that allegiance to the Irish Free State’.

Mr O’Reilly, I also took an oath and have no problem with transferring that allegiance to the Free State.

Mr Murphy ‘The opinion of the people is for the Treaty’

But Boylan was not to be moved; ‘I don’t wish to say anything. The resolution speaks for itself. We were elected as republicans. That is all’.

Some in the County Council wanted no vote to be taken in order to preserve unity. But the chairman insisted, ‘We must voice the opinion of the people’ A Pro-Treaty resolution was passed.[15]

Two obvious points of attack for anti-Treatyites in the border area were the Treaty’s acceptance of partition and its lack of any clauses dealing with further land reform. But at this early stage, the anti-Treatyites’ arguments were much simpler; men, in some cases their friends and families, had died for an Irish Republic and they were not going to settle for any less. The Republic was a kind of bond with the dead, sealed with their blood.

The arguments of anti-Treatyites were not sophisticated; an Irish Republic had been declared, blood had been shed for it and they would not accept its surrender.

The debate at Cavan Farmers’ Union on January 3rd highlighted the point evocatively. At Cavan Town Hall, Thomas Smith, a pro-Treaty Sinn Fein member, argued about ‘freedom to achieve freedom’, quoting Michael Collins. Ireland he argued, now had control over education, industry, finance, policing and the army. He cited the support for the Treaty of Collins, Arthur Griffith and Sean MacEoin, an IRA legend in the locality, ‘whom the Irish nation honours as a hero’.

Michael Sheridan took up the anti-Treaty argument. ‘Freedom’, he declared, ‘was won by a sacrifice of lives’. It was wrung from England’. John Redmond, Lord rest him, could have had this in 1914 if he had utilised his own forces [Heckler: ‘then why didn’t he?’] without Easter Week, or 1920 or 1921’. ‘The Treaty’, Sheridan went on, ‘is not the freedom of Pearse or Tone [who talked about] ‘the ‘blood of Irishmen to redeem the soul of Ireland’.

Here came the crux of the debate. A heckler shouted, ‘Are you going to shed it?’

Sheridan was taken aback. ‘That’, he responded, ‘is hardly fair. My family were prepared to shed blood and did shed it, the only sacrifice of life in Cavan and I am not ashamed of it’

Chairman: ‘the man did not know’

Michael Sheridan’s brother Thomas had in fact been shot dead by the RIC in an arms raid in 1920, one of only three IRA Volunteers to be killed in the County during the conflict (another Cavan IRA man was killed just over the county border in Leitrim).[16]. His IRA commander Paul Galligan later voted for the Treaty.

In May of 1920, Galligan had sent his West Cavan unit to ambush two RIC men at a fair in Crossdowney to take their weapons, but, “strict orders were given by the battalion OC [Galligan] that no lives were to be taken in the attempt”. In fact, when the police were challenged, they opened fire with their pistols. In a shootout, one of the Volunteers, Thomas Sheridan, Michael’s brother, was shot and mortally wounded; his brother Paul and one of the policemen were also injured. The police swore they would kill the other Sheridan brothers if the wounded sergeant died and set fire to the thatched roof of the Sheridan house that night. The roof fell in but the house itself was saved by the efforts of the neighbours.[17]

So in 1922, Michael Sheridan was in no mood for compromise. He resumed, ‘The threat of force is not a good argument for the Treaty and anyway it is mere bluff’. Though he conceded, ‘Mine is voice in the wilderness I know’. What he said next though is probably most revealing about the anti-Treaty Republicans’ stance. It was not so much an ideology, in the sense of a coherent world view as a mentality, and is worth quoting in full;

‘England may in the future subject Ireland to the same tyranny if a Republic is proclaimed. I am not a doctrinaire republican, Strictly speaking I am not saying what form of government Ireland should have but I implicitly believe in complete and absolute independence from England.’

‘I will never consent to the Treaty. I have been through the mill, I saw England’s paid assassins put my father against a wall with a revolver against his breast and the abuse of my aged mother looking for my wounded brother’. I have looked down the barrel of revolvers’. We must forgive but we won’t forget’. We must break the last link with England’ [Applause].

The Chairman concluded the meeting; ‘I agree with Mr Sheridan but I am not sure the war threat is bluff, there is no guarantee… The majority of people in Cavan know very little about what parts of Ireland suffered while the fighting on… and that was only child’s play towards what real war would be like’. .[18]

The Treaty was endorsed at the meeting but chair praised the ‘pluck and bravery of Mr Sheridan’.[19]

That Cavan and counties like it had not pulled their weight in the war was a sensitive charge. Only ten people died in Cavan compared to nearly 500 in County Cork. But Cork had nearly 400,000 inhabitants compared to Cavan’s 90,000. The entire border area with a combined population of roughly 450,000, from 1919-21 saw a death toll of about 150, with hundreds more injured. Casualties were still well under those for areas with comparable populations; Cork, Belfast or Dublin, but do indicate a considerable level of political violence. [20]

‘The trouble’ had certainly been bad enough for people not to want it to resume. Back in November IRA Cavan commander Paul Galligan had told a crowd of supporters that he, ‘Regretted it has been said of Cavan, inside and out that it did not take its place in the fighting movement, but … The difficulties might have been for the best’.[21]

The tragedy for the likes of Michael Sheridan was that their determination to validate their sacrifices and those of their comrades could only result in more violence.

‘We are anxious not to lose the services of President de Valera’

A few months later the Chairman or his armed representatives were very likely hunting Michael Sheridan, since in late March 1922 the IRA formally split over the Treaty into antagonistic factions and in late June the hostility boiled over into all-out Civil War. But one of the surprising things about the initial local Treaty debates is the lack of animosity between the rival sides.

Certainly pro-Treaty Republicans were dismissive at times of anti-Treaty ‘diehards’, At the Monaghan meeting one Father Murphy expressed the view that, ‘The anti-Treatyites have not got the intelligence to reason it out’. They were scared, he argued of someone asking ‘where is your republic now?’ ‘But the Treaty will get the last trace of khaki [British soldiers] out of the country in 10 years’.[22]

But there was also a clear desire to avoid disunity to patch up the quarrels caused by the Treaty. The pro-Treaty motion in Monaghan was seconded by a Father Coyle who declared, ‘Clontibret urges Mr. de Valera to bow the will of the people’. The Free State has placed the ball in front of the goal and he can kick it in any time he wants’. De Valera in other words was still considered by pro-Treaty supporters to be the natural Irish leader. Coyle concluded; ‘I hope opponents can shake hands with other side’.

There was initially little pro-Treaty bitterness towards anti-Treaty leader de Valera at local level and it has hoped that a compromise could be worked out.

The pro-Treaty proposal was unanimously passed by Monaghan County Council. However it also resolved, ‘We are anxious not to lose the services of President de Valera’.[23]

Similarly, the Anglo Celt newspaper reported of a ‘Prominent Methodist’, a ‘Cavan man returned from New York, son of clergyman’, ‘an Irish Protestant with no bigotry in his blood’, who the paper reported, said in a public speech, ‘to refuse it [the Treaty] would be suicide’. ‘I am a consistent Home Ruler’. I stand with Griffith and Collins without any prejudice to my honest, brave friend de Valera.’ [24]

And such apparent bi-partisanship percolated even into the region’s elected representatives. After a stormy debate, the Dáil narrowly passed the Treaty on January 7 1922, by 64 votes to 57. Paul Galligan, TD for West Cavan, voted for the Treaty as a TD in January 1922 but also voted for Eamon de Valera as President, the man who led political opposition to the Treaty. De Valera of course was not re-elected and began what turned into bitter and eventually armed opposition to the Treaty and his former comrades.

Within seven months, nationalists would be killing each other over the Treaty.

Ahead lay seven tortuous months in the border counties. Within two months the British forces would pull out leaving the IRA, increasingly divided though it was, in control of all the territory along the southern side of the border. There would be an on-again, off-again war between them the Ulster Special Constabulary across the border. There were also occasional clashes between pro and anti-Treaty IRA units until Civil War finally broke out on June 28 1922. Law and order would also further deteriorate in the months ahead. It was not until well into 1923 that some sort of peace was restored to the region.

As of January 8, 1922, the day after the Dail’s approving of the Treaty, no one knew this of course. It appeared as if the debate over the Treaty, fiery thought it sometimes was, had been amicably resolved. And had matters been left to locals along the border, war with Northern Ireland was probably considerably more likely than civil war over the Treaty.

But the north midlands border region could not be insulated from the rest of the new Irish Free State. The 26 counties’ descent into internecine strife would eventually drag in all parts of the country. Michael Sheridan and other idealistic and uncompromising anti-Treaty Republicans, would indeed see a further ‘blood of Irishmen shed to redeem the soul of Ireland’, though perhaps, in the end, they lived to regret it.

References

[1] Anglo Celt, December 10, 1921

[2] Anglo Celt November 17, 1921

[3] Anglo-Celt, November-December 1921

[4] BMH WS 1148 Patrick J Casey IRA Newry

[5] Anglo Celt, December 17, 1921

[6] Fearghal McGarry, Eoin O’Duffy a Self-Made Hero, p88

[7] Matthew Lewis, Frank Aiken’s War, the Irish Revolution 1916-1923, p115

[8] Galligan papers, UCD archives.

[9] Seamus MacDiarmada, Witness Statement BMH

[10] Anglo Celt January 7, 1922

[11] Anglo Celt January 7, 1922

[12] The Anglo Celt, January 7, 1922

[13] Anglo Celt January 7, 1922

[14] Anglo Celt January 7, 1922

[15] Anglo Celt January 7, 1922

[16] For IRA fatalities, see IRA monument, the Courthouse, Cavan town.

[17] Sean Sheridan Witness Statement BMH

[18] Anglo Celt January 7, 1922

[19] Anglo Celt January 7, 1922

[20] Counting the border area in question as including North Longford and Leitrim as well as the south of counties Armagh, Tyrone, Fermanagh and Down as well as all of counties Cavan, Monaghan and Louth. Population figures are taken from the 1911 census. Figures for those killed in the period taken from Eunan O’Halpin, Counting Terror, in David Fitzpatrick Ed., Terror in Ireland, p152, also from a survey of the Anglo Celt newspaper 1920 – 1922 and the Appendix of Lewis, Frank Aiken’s War, p224

[21] Anglo Celt November 10, 1922

[22] Anglo Celt, January 7, 1921

[23] Anglo Celt January 7, 1922

[24] Anglo Celt, January 7, 1921