‘Solid Men’ – The Irish in New York Politics, 1880-1920

How the Irish conquered political power in New York city. By Shay Dunphy.

According to Lawrence McCaffrey, an authority on the Irish Catholic diaspora in the United States of America, Irish Catholics blended the methodology and principles of Anglo-American Protestant politics with their overwhelming sense of community and gregarious personalities into a distinct brand of politics. Perhaps no other era could provide better evidence of this assertion than in American municipal politics within the period leading from the 1880’s right up to the 1920’s.

In Boston, Chicago and San Francisco in the 1880’s, Irish politicians heavily influenced municipal politics but it was New York that stood out from the pack; it ran Tammany Hall. Set up in 1788, ‘The Hall’ was to become the single most important factor why the Irish ran New York from 1880, when the city elected it’s first Irish Catholic mayor – the Cobh-born William R. Grace – until lower-east side born Al Smith failed in his bid to obtain the office of President of the United States in the 1920’s.

The Origin of ‘Tammany Hall politics’

Tammany Hall began its days as a fraternal society with social and charitable principles. Originally, it had no involvement in politics and ironically, espoused a form of exclusive anti-immigrant, ‘Americanism’; an ideology that did not incorporate Irish Catholics into the American nation. This narrow nationalism bore similarities to the sectarian “know-nothing” movement of the 1840s. At that time the Catholic Archbishop of New York, Tyrone man John ‘Dagger’ Hughes, had informed the ‘nativists’ that the city would be turned into ‘another Moscow’ (in reference to the burning of that city as the Russians retreated from Napoleon in 1812) if any of the city’s Catholic churches were touched.

The threat carried considerable weight, considering Irish immigrants had been arriving in their thousands in New York since before the Great Famine. So with the over two million Irish to arrive in America between 1845 and 1854 and with many settling permanently in New York and Brooklyn – both cities not yet bridged to become one – this would ensure that in a short period of time, the entire population would be a quarter Irish in composition.

From the outset, the divisions between the Irish and the nativists were pervasive both in cultural and religious aspects but these divisions were accentuated by political allegiance. White Anglo-Saxon Protestants in the 1880’s were firm in their support of the Republican Party, ‘We are Republicans and don’t propose to leave our party and identify ourselves with a party whose antecedents have been rum, Romanism and rebellion’, one contemporary rank and file party member wrote.

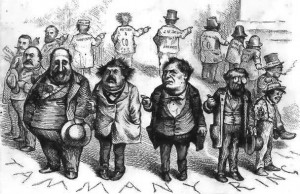

Irish Catholic support for the Democratic Party, as a result of such attitudes, was copper fastened. In fact, the New York City Irish would eventually gain next to thorough control of the local branch of the Democratic organisation before long. The vehicle for control was of course Tammany Hall, a political machine reinvented by the Irish.

When “Honest” John Kelly assumed control in 1871 after the disgraced Tammany leader William Marcy Tweed was thrown into gaol for political corruption, he turned Tammany into an organisation that became a cohesive force in New York politics. Its structure began to mirror the organisation of which the vast majority of its members and supporters also subscribed to, the Catholic Church.

Local district leaders performed their duties much as bishops did, while precinct leaders similarly were its parish priests, floating around the Irish neighbourhoods, ever cultivating the people’s faith in the organisation’s candidate for municipal office. The district bosses were the so-called “bhoys, who everybody knew in the neighbourhood. They usually owned bars that often doubled up as Tammany clubhouses. They had the power to get people jobs and better their economic position. They also acted as the go-between for the district leaders who could hand out the really big jobs, particularly those in the New York Police Department. This perhaps, explains the predominance of the Irish cop in old American movies.

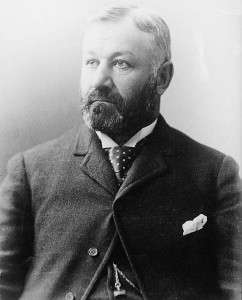

The Rise and Fall of ‘Boss Croker’

The 1880’s marked the beginning of the golden age of Tammany Hall. In this era, politics for the organisation became big business. The new ‘boss’ to emerge was Richard Croker, a street-wise hard man, born in Co. Cork but brought to America as a young child. He quite literally fought his way to the position of ‘Grand Sachem’ which made him the de facto leader of Tammany Hall. Croker saw to it that Tammany had its hands in virtually every business in New York, whether it was railroad construction or the ‘rag and bone’ business in the slums.

Under Croker, Tammany casually abandoned any business ethics it may have had whenever it saw fit. Everyone on the payroll, whether in the police department or elsewhere, had a duty to pay a percentage of their income to Tammany Hall. This was then used to pay off voters in the districts, to convince them that a Tammany candidate up for election for a municipal post was the man for the job. However, not all of the money was used for this purpose. “Boss” Croker also attained for himself a mansion off Fifth Avenue, was able to regularly summer in Europe and also kept a racehorse. All this despite the fact that the only public office Croker ever held was that of the relatively minor position of city chamberlain.

The parochialism that Croker cultivated meant that social policy was not an objective nor was the state of the nation of any real concern. Washington D.C., for the Irish living in the tenement and slum neighbourhoods of New York, was a distant place, only read about in the newspapers. Tammany reflected this in that it isolated itself from the Democratic Party in the rest of the country. Nonetheless, by 1894, the Irish seemed to have attained political hegemony in New York City, as one contemporary politician asserted, ‘New York has ceased to be an interesting study for municipal experts. It is clean given over to Irish domination’.

However, for Croker and Tammany, national matters began to eventually impinge on New York municipal politics by the early eighteen nineties. In 1893 the United States faced an economic crisis that resulted in high unemployment levels, which directly affected New York. Political parties who espoused reform, such as the Workingman’s Party, were, worryingly for Croker, eating into the Tammany electoral pie.

The election of mayor for New York in this period was under contestation and the largely German – but also increasingly Irish-backed Workingman’s Party entered the election race. Things were already ominous for Tammany as some Democratic Party members had recently aligned themselves with a rival political machine called the “CountyDemocracy”. Reformers, the County Democracy may have been, and anti-immigrant to boot but Croker calculated that they were lesser of the two evils compared to the Workingman’s candidate Henry George.

As already pointed out, politics for Croker was a business. Supporting reform measures promulgated by George therefore was hardly beneficial. In employing tactics of electoral fraud, Tammany was instrumental in denying New York City radical reform – such as improvement to slum housing and workers’ rights – and in the process Irish slum dwellers and voters from social justice. The result of their electoral chicanery was that the Workingman’s Party was defeated in the election, despite having massive support. The Tammany line on reform was further emphasised by their brandishing of the slogan, “To hell with reform!”.

Time was running out for Croker however, as a Protestant clergyman, Dr. Charles Parkhurst, was now hot on his heels. Parkhurst was to conduct an anti-vice crusade in an attempt to expose Croker and Tammany Hall’s shady activities.

By virtue of the detective work carried out by Parkhurst and a professional detective sidekick, what was exposed was a political cesspit. As a result, committees were set up in the New York legislature with testimonies given to buttress the Parkhurst findings. These findings included evidence of the police taking bribes from Tammany as well as the collection of protection money for the organisation’s leaders, who had also been organising the gambling rings, liquor trade and prostitution rackets in New York. Croker was exposed as Tweed had been before him as yet another symbol of corrupt boss politics.

He amazingly escaped prosecution however, voluntarily gave up the leadership of Tammany Hall in 1903 and returned to Ireland to live a gentleman’s life on his country estate where he died in 1922.

‘Silent Charlie’ Murphy and the Rise of Al Smith

Tammany Hall, despite such negative publicity, was not destroyed however. With Croker out of the scene, Charles Francis Murphy now took over the Tammany reins. His entry into politics was typical of any Irish-American Politician. He was the owner of a number of public houses in the east-side where he soon became a district leader, a so called “solid-man” who commanded respect. Murphy in his accession as leader, was a breath of fresh air for Tammany.

His tenure, which lasted twenty years, was marked by the emergence of two figures, who would not only come to be associated with New York but also national politics.

Murphy spent much of his time as the leader of Tammany engaged in a battle with a young and extremely wealthy publisher, William Randolph Hearst. The latter espoused the political objectives of the Workingman’s Party. As George had been a persistent thorn in Croker’s side so would Hearst for Murphy.

Hearst’s vision was that of a New York that saw municipal ownership of the gas, ice and streetcar companies. He was to become one of the founders of the municipal ownership league in 1904. He had in the past, run as a Tammany candidate for a seat in congress but now incurred the wrath of its leaders. In 1905, he ran as a league candidate in the New York mayoralty election – which he actually won – but Tammany had him counted out fraudulently, with thousands of his votes confiscated. Old habits died hard it seems for the organisation.

In 1906, at the New York State Democratic convention; Hearst was denied nomination, this time for governor, due to the influence of Murphy. The battle between Tammany and Hearst would continue but ultimately be resolved by the emergence of a shining light from within Murphy’s ranks.

Al Smith was a lower east side Irish Catholic born and reared under the shadow of the Brooklyn Bridge. He was the supreme product of machine politics. In a sense though, he actually became bigger than the organisation that spawned him. Smith believed in his early days as a Tammany man that corruption in New York politics was not the main problem that faced the organisation. Rather, he believed the bigger problem came from those Republicans with reformer ideals, who attempted to break the monopoly of political power that the Irish had gained for themselves in the city.

Smith was an Organisation-man to the core; Murphy viewed him as his own personal creation. Ironically however, Smith evolved into a social reformer and eventually grew out of the influence that Tammany had long exercised over him. After his election to the New York State Assembly in Albany, he worked diligently and became known as the “Henchman of Tammany Hall”. Anything that Tammany Hall requested, Smith ensured was carried out in the assembly. Such orders were largely concerned with the quashing of reform measures, especially patronage reform.

By 1911, the Democratic Party had finally ended many years of Republican control of the houses of the New YorkState legislature. In 1913, Smith became speaker placing Murphy and Tammany Hall in an even more dominating position in the state legislature in Albany. Murphy was indirectly changing the character of New York Irish politics. He continuously played a prominent role in the organisation but it was a taciturn one, evidenced by his nickname; “Silent Charlie”. Traditionally, Tammany leaders had thought it imperative to be in Albany to ensure Tammany objectives were pursued at state level. However, Murphy thought this unnecessary, such was his trust in the capability and unquestionable loyalty of Al Smith.

Nineteen eleven was an important turning point in New York Irish political history also because Smith’s influence was such that he could now involve himself in social and economic reform.

The Triangle Shirt factory disaster of New York in that year, where dozens of female immigrant workers– mostly Italian and Irish – perished in a fire, aroused public awareness nationally of low wage earners’ working conditions. Smith was instrumental in the setting up of a Factory Commission that investigated industrial practices in the city.

What resulted was a three-volume report that was instrumental in passing through the New York legislature laws that included shorter working hours and better conditions for female workers. What is particularly ironic about these reforms which Smith help bring about is that they were challenged by the very Republicans who had espoused previous reform measures that Tammany had opposed. The reason for such opposition can be traced to the fact that the Republican Party had begun to make close connections with factory owners and others engaged in big business. Therefore, it was simply not in their interest to stir the pot.

Smith’s star was rising and in 1918 he was nominated for governor of New York – the first time in its fifty year history that a Tammany governor was elected.

Conclusion

In his book “Beyond the Melting Pot”, Daniel Patrick Moynihan, another Irish-American historian, suggests that the Irish politician in New York was incapable of reaching beyond the parochialism of Tammany Hall. His claim is that the Irish in New York did not know how to capitalise on their power. This can be substantiated to a certain extent by looking at Tammany Hall activity towards the close of the 19th century. However, on closer inspection, the forty years from 1880-1920 is a relatively short period of time for an ethnic group to reach so far into a political system, that had previously been so dominated by Anglo-Americans.

Religious bigotry had contributed somewhat to the presidential election defeat of Al Smith in 1928 and indicated that the Irish had still some lack of respect – not to mention political ground – to overcome among the American electorate. Nonetheless, the Irish political experience of the late eighteen and early nineteen hundreds was an important chapter in the history of the Irish in America and in American politics overall. Irish politicians protected Irish Catholic interests and in the process encouraged other Catholic ethnic minorities to enter the political fray. Moreover, they also paved the way for the entry of non-Catholic immigrants such as the Jews into New York’s political life.

The Irish influence on American political life during this period was immense and has become part of the American folklore.

Sources

Glazer,Nathan& Moynihan, Daniel P. (eds.), Beyond the melting Pot: The negroes, Puerto Ricans, Jews , Italians and Irish of New York city, Cambridge (MIT Press), 1970

Kenny, Kevin, The American Irish: A History, Longman (New York), 2000

McCaffrey, Lawrence J.The Irish Catholic Diaspora in America, Washington D.C. (Catholic University of America Press), 1997.

Shannon, William V., The American Irish, New York (MacMillian), 1963

Walsh, James P., The Irish: America’s Political Class, New York (ARNO Press), 1976