Making Money in Dublin, 1500-2000

John Dorney reports from a conference on money-making in the Irish capital. The Conference was organized by Trinity College Dublin and in particular Lisa Marie Griffith and Ciaran Wallace on May 25, 2012.

A very crude theory of economic and social development of cities since the middle ages, in Europe at any rate, goes something like this;

First there is ‘feudalism’, where social rank and economic functions are hereditary. Trades are strictly regulated into guilds and merchants and producers must first get a monopoly from the political authority.

Second comes ‘mercantilism’, where trade is liberalized, perhaps gradually, as is production. Producers proliferate, as do merchants and rise or fall based on their economic performance. Quicker travel means trade with a wider area. But because of limits of technology, production remains on a limited scale.

‘Making Money in Dublin’ gave snapshots of Dublin’s economic and social life across 4 centuries

Third come the ‘capitalist’ stage, where a combination of capital, freely lent at interest and mechanized technology allows for large scale production of cheap goods – which can also be increasingly rapidly exported and imported. Urban centres explode in size as people come to work in new factories. Capital also concentrates in very large new retail units – department stores, later shopping centres.

And finally (to date), the post-industrial stage. Where much heavy industry has generally relocated to countries with cheaper labour. Cities are often cleared of actual production and specialize in, ‘the knowledge economy’ – that is the design and maintenance of computer systems and other technological innovations, as well selling consumer goods and providing various customer services.

Very generally this process is usually accompanied by political changes. Whereas in medieval times entrance into the city, which is usually walled, is restricted and political rights, to citizens, are hereditary. As money becomes more important than rank, walls are pulled down, populations come and go from the city. Political rights are determined by property and whether a person pays taxes rather than by whether or not one’s grandfather belonged to the guild of carpenters. By the end of our stages, political rights in the city are usually democratized further, to those citizens who pay few or even no taxes.

Such a vulgar oversimplification would no doubt have economic and social historians shaking their heads sadly. Nevertheless it does provide a useful shorthand when thinking about urban history and helps to link the diverse and interesting contributions to the symposium, “Making Money in Dublin” organized by Trinity College on May 25, 2012.

‘None of the Irish nation’

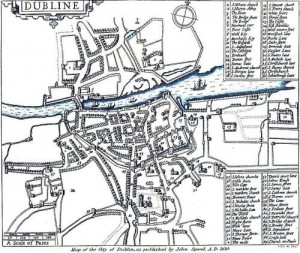

If we venture back to 1500 or so, Dublin city was a tightly knit place of around 5,000-10,000 people. It was very small in area, an enclave hugging the south side of the Liffey of no more than two square kilometres. Dublin was also an English city, feeling itself to be a besieged enclave of ‘civility’ in a sea of Gaelic Irish, ‘barbarism’.

Research by Sparky Booker into the franchise rolls (the record of the freemen of the city – those with the right to elect the city Aldermen, who then elected the Mayor) shows us they were guild members, those who inherited the right or those admitted, ‘by special grace of the mayor’. Surprisingly, the enfranchised seem to have to have included women.

Still more surprising, in the context of late medieval Ireland, was that some 12% of the freemen had Irish surnames. This was despite a stream of legislation in the late 15h century expelling the Irish from the city – Gaelic Irish people were banned from being citizens (‘none of the Irish nation’ were permitted) in 1440, not allowed to live in city by order 1450, in 1469, apprentices to the trades had to be ‘of English birth’, and in 1475, tradesmen and merchants were barred from taking on Irish apprentices on pain of losing their own franchise. Even the distinctive Irish hairstyles and clothes were banned from the city in 1497.

Despite penal legislation excluding them from the city, about 12% of the medieval franchise holders in Dublin were of Gaelic Irish origin, where they occupied niche economic roles.

In spite of all of this, a number of Irish family names appear over generations, especially, Kelly, Colman, Nolan, Neill, Dowgan. These families tended to be from the immediate hinterland of the city. The Kellys for instance were from the modern Dublin/Wicklow Kildare border, near Newcastle, County Dublin and their own town, Ballymackelly. The O’Neills of Dublin originated around Clondalkin.

It struck me that their position was little like that of well-heeled Jewish families in central Europe. Like the Jews, they assimilated into the dominant culture. their names on the rolls, Booker tells us, were recognizably Irish but generally anglicized, the ‘O’ was often omitted and Irish first names are present in the rolls, but rare.

And like the Jews in other parts of Europe they occupied niche economic and professional activities. The Kellys, it seems, first show up in Dublin rolls 1469 as clerks. The other Irish families specialized in law, as clergy or clerks or certain trades such as tanners, goldsmiths. Access to the networks of real power were closed to them though. None were admitted to the franchise roll ‘by special grace of the mayor’.

A feature of economic development has been the gradual dismantling of such rigid and codified regulation of ethnicity in the city. The modern city is place where people from all over the world come and go. Could it be that strictly regulating the economy naturally extends to regulating who lives in the city and that more impersonal capitalism enables people to ‘live and let live’?

Origins of modern Dublin

Dublin in the 15 and 1600s, as well as beginning to feel the forces of economic modernization, also went through a painful process of religious conflict. Paradoxically as I have written elsewhere on The Irish Story, the descendants of ultra-English medieval Dubliners ‘became Irish’ after the reformation by remaining Catholic. By the 1640s and 50s, and during the religious wars that wracked Ireland in those years, the new English Protestant authorities were issuing orders expelling all Catholics from the city limits.

Protestant-dominated Dublin, from roughly 1650 until about 1800, also saw the end of much of medieval Dublin’s streetscape and the construction of many of what are still the finest buildings in the city. The muddle of the old city was replaced by clear, straight lines, and wide avenues constructed to the east of the old walled town. Dame Street, for instance, was laid out in fine style to connect the Castle with the City Hall – which was constructed by the city’s merchants in the mid 18th century – and connected with another monument to 18th century boulevards, Sackville [now O’Connell] Street with a new, wide bridge over the Liffey.

The late 17th and 18th centuries saw a boom in trade and consumption and saw the construction of some of Dublin’s finest buildings

Colm Lennon, of Maynooth University, tracked the fortunes of Dublin’s Custom House. It was originally built close to where the modern civic offices are located at Wood Quay but moved to its current location – down river near the port and on the northside – in 1781, when work started on James Gandon’s grand design (sadly torched in 1921).

An interesting feature of Lennon’s talk was the origin of many of the street names of the city in this period. Aungier Street and Longford Street for instance are named after the gentlemen-businessmen who laid out markets there in the 18th century. Humphrey Jervis left his name to the street on the northside beside the markets and gardens he set up there and the Earl of Clarendon left us Clarendon Street after his own market.

The Liberties are now often thought of as the heart of Old Dublin, but were actually outside the city walls in medieval times. The Earl of Meath’s liberty in particular became the centre of industry in the city, leaving us street names such as Weavers’ Square and The Tenters (where the linen was dried).

Alison Fitzgerald showed how the burgeoning of the wealthy classes in 18th century Dublin created a market for luxury goods such as watches, fine china, gold jewellery and more. But it could be a perilous business to be in. Many products were sold on credit and ‘the better sort’, who bought them could not really be pressured into paying. The goldsmith Jeremiah D’Olier (whose family also gave their name to another Dublin street), appealed urgently, on his retirement in 1770, for all outstanding debts to be settled. Many such traders went out of business. Similarly Johanna Archbold demonstrated that publishers, targeting Dublin’s literate classes (a finite market at this date, one imagines) walked a fine line between success and bankruptcy.

Large scale commercial activity requires credit. Up to this point, Merchants with money to spare would simply lend it to each other and hope for the best. Trish Stapleton showed how many widows of businessmen would often invest their inheritance in this way.

Banking as we understand it, i.e. holding money and giving long term loans at fixed interest, came to Dublin in the late 1690s. Most early bankers came from religious minorities (Presbyterian, Quaker Huguenot), the most successful of which was the Huguenot partnership of La Touche and Kane, who set up in 1716.

Patrick Walshe, in a stimulating paper on this topic showed how already in the 1720s, Banks were too vital to the economy to be allowed to fail. In 1723 the Bank of England almost went bankrupt after getting caught up in the South Sea Island bubble and had to be, ‘bailed out’, in modern terminology, for 50% of its losses. In Ireland, the Dublin banks’ losses were also significant and as a result a National Bank of Ireland was set up, interest rates fixed and bank notes standardized. (More on early modern bank bailouts here).

Eoin Magennis showed that early capitalism was in fact subject to all kinds of formal and informal regulations by looking at the case of coal – increasingly a vital commodity for the growing population of urban poor. Prices were often set by the guilds or the corporation and sometimes riotous crowds invaded the coal yards to enforce their own ‘just price’. In 1800, a public coal yard was set up to regulate supply and price – presumably in the interests of public order. It was abolished in the early 19th century as ideas spread of ‘laissez faire’ capitalism and non-interference in economic matters.

The 18th century city inherited the political system of medieval Dublin, in that (all-Protestant) freemen elected Aldermen, who elected a Mayor. But by the late 18th century this had no bearing on who actually lived and worked in the growing city.

Because of this, it seems that early modern Dublin was a surprisingly cosmopolitan place. The archeologist Frank Miles told the story of one John Odacio, fom Alteri, near Genoa in northern Italy – a region famous for glass-making. Odacio was an alchemist, who used sand and ash to make fine crystal by a secret formula and who set up shop in Smithfield in Dublin between 1675 and his death in 1696.

His travels have previously taken him to Nijmegen and Rotterdam in the Netherlands until a French invasion in 1675 forced him to flee and he secured got Royal patent from the English monarch to set up in Dublin. The site of his workshop was excavated in 2008 and samples of his work in Dublin have been found as far away as Jamestown, Virginia, and Port Royal, Jamaica. Odacio may even have located in Ireland to ease export to the New World. Globalization, apparently is nothing new.

Industrial Dublin?

One result of the mobility of people into and out of the city is that the Protestant majority was relatively fleeting. Catholics migrating from the rest of Ireland to Dublin became a majority there by the late 18th century, They effectively conquered political power in the mid 19th century when Thomas Drummond, a reforming Liberal Under Secretary for Ireland, introduced the Corporations Act in 1840, which swept away both hereditary rights to municipal voting and religious discrimination in favour of votes for all property holders and rate payers over a certain amount per year.

Mass consumption meant mass politics. Votes for the Corporation were extended to all rate payers in 1898 an to all residents in the city as late as the 1970s -albeit in between, after Irish independence in 1922, most powers were stripped from local government.

Ireland, it is often repeated, apart from Belfast, did not have an industrial revolution. While there is some truth in this, Dublin was not that different from many 19th century cities in that it grew steadily throughout the century. Dublin did have some industry, notably brewing and distilling. By the 20th century it also hosted factories, for instance for Imperial Tobacco and John Player cigarettes in its working class suburbs.

This was also the age of mass consumption. William Martin Murphy, notorious in labour circles for his part in the 1913 Lockout, was one of the first Catholic and nationalist millionaires in Dublin and famously built a business empire on the new phenomena of the mass media. He owned the Irish Independent and Freeman’s Journal, most of the Dublin tramway system and many of the new Department Stores. Stephanie Rains demonstrated that hundreds of small publications sprung up in the early 20th century in Dublin but that most could not compete with Murphy’s colossus.

Dublin in the classical industrial age had some pruduction but the real money was to be made in constructing and property development, much as in the early 21st century.

But, in a way that is still familiar today, the biggest money was to be made in building and selling houses in the city’s new suburbs – around 35% of Dubin’s current housing was built in the 1800s. Susan Galavan spoke on how builders, timber merchants and land speculators (often the same people) became millionaires on the back of the construction of the upper middle class suburbs at Ballsbridge and Kingstown [Dun Laoghaire] in the 19th century. Similarly Ruth McManus charted the rise of the Crampton family, who started out as builders in 1879, but by the early 20th century had diversified into many other areas including retail and even public houses.

Irish independence made some difference to the Cramptons, but not much. In 1928 they were targeted by the Anti-Imperialist League (a front for the IRA) as an ‘outpost of Empire’, for having flown the Union Jack on Remembrance Day. But the company neatly accommodated themselves to the Irish state and, after Fianna Fail began a state-led plan in the 1930s to develop Irish indigenous industry, the Cramptons got many of the best contracts, constructing, for instance, a huge office for the National Sweepstakes at Ballsbridge.

Similarly, up to the 1970s and EEC accession, economic nationalism dictated that tarrifs be put on importing foreign products, which meant that many firms located factories in Ireland to assemble products and get around the tarrif wall. For the Cramptons and their ilk, this meant more business again in contructing these factories.

By the late 20th century, the city had taken on much of its modern form. The suburbs, which had started slowly and elegantly in the 19th century in red-bricked places such as Drumcondra, Rathmines and Kilmainham, ballooned from the 1960s, leaving old Dublin surrounded by acre after acre of suburban housing estates. Cramptons certainly seem to have moved with the times, building, along with housing, new office blocks and the first shopping centre in Dublin at Stillorgan in the mid 1960s.

New technology

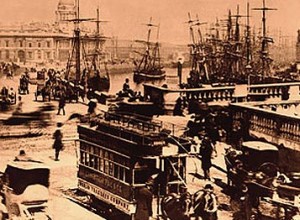

Since Dublin was never really an industrial city, one hesitates a little to speak of deindustrialization in the 1980s. But certainly the rise of technology, which meant that places such as Dublin Port needed far less manpower, and the lifting of tariff walls, which eliminated the need for assembly factories in Ireland, caused high unemployment in the city.

Since Dublin was never really an industrial city, one hesitates a little to speak of deindustrialization in the 1980s. But certainly the rise of technology, which meant that places such as Dublin Port needed far less manpower, and the lifting of tariff walls, which eliminated the need for assembly factories in Ireland, caused high unemployment in the city.

By the 1990s though, Ireland like much of the western world started to feel the benefits of a new type of industry based on technical expertise in new digital technology. In these days of national self disgust, it often said that the ‘Celtic Tiger’ boom was merely property speculation and foreign investment encouraged by very low taxes.

However it is encouraging to remember that there was also a mini-boom in Irish owned IT companies in the 1990s. Chris Horn, who founded IONA Technologies (who sell a programme linking computer systems) in 1991, with start up capital of only £3,000, sold it in 2008, just before the banking crisis for a sum in the hundreds of million of euros.

As well as property seculation, Celtic Tiger Dublin also had some genuine Irish success stories, especially in the realm of new technologies.

Horn spoke eloquently about how he and three fellow technology graduates from Trinity College managed to market their product in the United States and then sell it to Europe and Asia. A little like John Odacio, the Italian glass-maker in Smithfield 400 years before. Horn said he now plans to reinvest in the booming technology sector in Dublin. While IT is not that labour intensive and needs a very particular kind of expertise, which relatively few workers in Dublin possess, this is certainly welcome news.

It is long way in time and space from the tiny walled city of Dublin in 1500, where each tradesmen had to acquire a hereditary right to his profession to the multi-national, ever changing urban sprawl that is Dublin in 2012. Theories of urban and economic development can help us to understand some of this story. But what these snapshots of Dublin history show mostly is the remarkable diversity and adaptability of city life throughout the centuries.