Book Review: The Year of Disappearances. Political Killings in Cork 1921-1922

Pádraig Óg Ó Ruairc challenges the claims in Gerard Murphy’s recent book, The Year of Disappearances. Political Killings in Cork 1921 – 1922.

Pádraig Óg Ó Ruairc challenges the claims in Gerard Murphy’s recent book, The Year of Disappearances. Political Killings in Cork 1921 – 1922.

Professor Eunan O’ Halpin of Trinity College, was prophetic in his endorsement of Gerard Murphy’s recent book, The Year of Disappearances. Political Killings in Cork 1921 – 1922. O’ Halpin stated the book ‘…is bound to stir up controversy.’ Murphy claims that the I.R.A. murdered dozens of Protestant and Unionist citizens of Cork between July 1921 and August 1922. However close analysis reveals that the historical documents Murphy uses as evidence do not always support the claims in his book. Questions need to be asked about the reliability of Murphy’s research.

Murphy’s book examines the execution of suspected British spies by the I.R.A. In 1921 the I.R.A. was a secret guerrilla army where many orders would have been given orally and where written communication would frequently have been destroyed. As a result the evidence for the guilt or innocence of those the I.R.A. executed is often fragmentary. Murphy links these fragments together using supposition, coincidence, and local rumor. Murphy frequently relies on anonymous sources for information. Given the long running controversy caused when the late historian Peter Hart used anonymous sources to make controversial claims about the War of Independence, Murphy should not have made contentious charges about the same period without definite written evidence.

Murphy believes that the I.R.A. abducted teenagers from Unionist families during the conflict to put pressure on the British. He suggests many of these were killed and secretly buried but often fails to produce verifiable evidence to prove this. Even Murphy’s definition of what constitutes a teenager is problematic. Murphy refers to four British soldiers Privates Cannim, Powell, Morris and Dacker killed the night before the Truce as ‘teenage soldiers’ (p.16). None of the four were teenagers. They were aged 20, 20, 21 and 28 respectively. When questioned about this inaccuracy Gerard Murphy told the Sunday Tribune newspaper, ‘They are usually referred to in Cork as teenagers and this is why I referred to them as such. I did not look up their ages.’* In this instance rather than conducting a quick internet search of the Commonwealth War Graves Commission which would have confirmed the soldiers ages in minutes Murphy instead relied on incorrect second-hand information and treated it as factual.

Rather than conducting a quick internet search of the Commonwealth War Graves Commission which would have confirmed the soldiers ages in minutes, Murphy relied on incorrect second-hand information and treated it as factual.

The lists of those killed by the IRA in Murphy’s book also pose difficulties. Murphy states that a person named Duggan was abducted and killed by the IRA in Cork sometime in July of 1921. There is no record of a person named Duggan being abducted at that time. Murphy does not state Duggan’s full name, sex and date or place of death in the book. He admits that, ‘Little or nothing is known about Duggan’ (p.35 ) Yet he automatically accepts Duggan’s death as historical fact.

Three Protestant Boys

Murphy’s lists of Cork civilians killed by the I.R.A. also lacks essential detail. It includes groupings of anonymous fatalities including ‘Three Merchants’ and ‘Six Prominent Citizens’ ( p.338 ) Crucially Murphy claims that the IRA in Cork did not target Protestants because of their religion until the War of Independence ended in July 1921 He writes that, ‘… the IRA campaign in the city, at least up to that point was not sectarian’ ( p.42 ). Murphy states that the IRA killed three Protestant teenagers from Cork between 11 – 15 July 1921. According to Murphy, the trio confessed they were British spies before being killed. Murphy sees this as a key event which launched the Cork IRA on a murderous sectarian campaign in late 1921 and early 1922. In his book Murphy insists that this event ‘…set in motion a whole witch hunt fuelled by suspicion and paranoia that led to dozens of deaths.’ (p. 306) The three victims are unnamed in Murphy’s work and he refers to them as ‘Three Protestant Boys’.

There is no record of three Protestant youths being abducted together in newspapers or police reports of the time. Nor is there any record of their existence or death in archival collections such as the Mulcahy Papers in the U.C.D. Archives. Other youths who disappeared, were abducted individually, and secretly executed by the IRA in Cork in the same period were recorded. How could the disappearance of this group of three have escaped the attention of their families, the press, the police and the British authorities? The logical conclusion is that the disappearance of the ‘Three Protestant Boys’, which Murphy claims sparked a sectarian campaign, was not recorded because it did not happen.

The logical conclusion is that the disappearance of the ‘Three Protestant Boys’, which Murphy claims sparked a sectarian campaign, was not recorded because it did not happen.

Murphy’s only information about the fate of the ‘Three Protestant Boys’ comes from one anonymous source. Murphy states that he was told ‘the story’ (his description – p.302) by the 89 year old son of an IRA veteran. Murphy states this man was informed ‘…by a Volunteer who waited until all connected to the event were themselves dead.’ ( p.302) Murphy does not state how the IRA veteran his 89 year old source supposedly heard the story from knew of the killings. Nor is he named anywhere in Murphy’s book. This third hand anonymous information cannot be verified or examined and therefore completely lacks credibility. Yet it is Murphy’s strongest evidence not only for the fate of the ‘Three Protestant Boys’ but also of their existence.

The Documentary Evidence

The Documentary Evidence

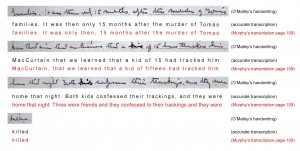

Murphy claims that the killings of these three were referred to by Connie Neenan in an account of his IRA activities recorded in writing by Ernie O’ Malley. (Ernie O’Malley Military Notebooks U.C.D. Archives P17b/112 p. 126) Murphy gives the following as an extract from this interview: ‘Three were friends and they confessed to their trackings and they were killed.’ This sentence is so central to Murphy’s thesis that he refers to it no less than 15 times in the book. Murphy also entitles the book’s 27th Chapter ‘Three Were Friends’. However the phrase ‘Three were friends…’ is not found anywhere in the document cited by Murphy.

The sentence in the account quoted by Murphy actually reads: ‘Both kids confessed their trackings, and they were killed.’ This transcription of the sentence has been confirmed by two other historians who have specialised in transcribing O’Malley’s notebooks. Namely O’Malley’s son Cormac K. H. O’Malley and Dr. John O’Callaghan of the University of Limerick. While O’Malley’s handwriting is difficult to read, this document is amongst the most legible interviews he recorded. It is clear beyond doubt that there are only nine words in the sentence. A comparison between Murphy’s transcription of the passage and the original (above) shows that Murphy frequently misidentified words, in one case reversed the order of two words, changed numerals to words and inserted several words that were not in the original.

Presumably Murphy mistook the B in ‘Both’ for the numeral ‘3’. Regardless, Murphy provides an extremely poor and misleading transcription of the sentence. It is clear from the original that Neenan was referring to two suspected spies executed before the Truce and therefore could not possibly have been referring to ‘Three Protestant Boys’ killed afterwards.

Gerard Murphy insists that the transcription of the document in his book is fully correct and accurate. This claim is paradoxical since Murphy gives at least three slightly different transcriptions of the sentence in his book (pp. 109, 149,306). When questioned about the accuracy of his transcription of this sentence Gerard Murphy told the Sunday Tribune newspaper, ‘To my eyes at least the word ‘friends’ is clearly legible. A blind man could see that the sentence has ten words not nine, excluding the 3.’

When contacted concerning the accuracy of Gerard Murphy’s transcription of the sentence and provided with a copy of the document in question, Gill & Macmillan, Murphy’s publishers stated; ‘It is not our intention, to insert ourselves into this scholarly dispute.’

Given the lack of any verifiable proof whatsoever that this incident ever happened, serious questions need to be raised about the dozens of deaths that Murphy claims were a result of it. Murphy makes over forty references to O’Malley’s handwritten documents in his book in support of his various claims. If Murphy was unable to read and accurately transcribe O’Malley’s interview with Neenan then the other references Murphy makes to O’Malley’s notebooks must also be treated as circumspect by the reader until they have been checked in the original.

By omitting three key words from his transcription Murphy has completely changed the meaning of the sentence. The original sentence implies that I.R.A. methods of gathering information were competent and precise. Murphy’s incorrect transcription of the sentence gives the opposite impression.

Finally Murphy’s inaccurate transcriptions are unfortunately not confined to handwritten documents. Murphy reproduces part of a typed IRA document issued by the 1st Cork Brigade. (O’Donoghue Papers National Library of Ireland MS 31 230) According to Murphy it directs IRA intelligence officers to examine letters addressed to ‘… any address or firm with which people generally deal…’

The document actually states that the IRA should be on the alert for letters sent to ‘… any address or firm with which people locally do not generally deal…’ By omitting three key words from his transcription Murphy has completely changed the meaning of the sentence. The original sentence implies that I.R.A. methods of gathering information were competent and precise. Murphy’s incorrect transcription of the sentence gives the opposite impression.

The flaws in Murphy’s work are often evident only when his original source material is examined. If Murphy can not accurately transcribe either the handwritten or typed documents he uses as evidence, then the claim that his book is a work of historical fact based around these documents is seriously questionable.

Pádraig Óg Ó Ruairc is a Ph D student at the University of Limerick. He is the author of Blood On The Banner – The Republican Struggle in Clare and The Battle For Limerick City both published by Mercier Press, Cork. He administrates the website www.warofindependence.info

*The quotations from Gerard Murphy above, are taken from his unpublished response to The Sunday Tribune newspaper and appear courtesy of The Sunday Tribune.