Today in Irish History – First Day of the 1641 Rebellion, October 23

~1641~

John Dorney looks at the outbreak of one of the bloodiest and most tragic rebellions in Irish history -the 1641 Rebellion.

John Dorney looks at the outbreak of one of the bloodiest and most tragic rebellions in Irish history -the 1641 Rebellion.

October 22 – 23 – The Foiled Plot

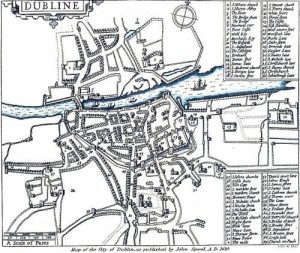

Sometime on Friday, October 22nd 1641, some 80 men from rural Leinster and Ulster made their way into Dublin, weapons hidden on their persons. They would not have attracted much attention, as the following day Saturday, October 23rd, was market day and the small, compact city was full of countrymen, come to buy or to sell livestock, seeds or crops.

The two men in charge of this band were Catholic gentry Rory O’More and Conor MacGuire. At a secret meeting on October 5th , they had, together with several other conspirators, including Hugh Og MacMahon and Phelim O’Neill, hatched a plot for insurrection. O’More and MacGuire were to seize Dublin Castle and its armoury of 10,000 weapons, and hold it until help came from insurgents in Wicklow under Hugh MacPhelim O’Byrne. Phelim O’Neill was to raise his kin and dependants to take a series of strongpoints across central Ulster.

A small group of rebels planned to seize Dublin Castle

The English garrison of Ireland, only some 2,000 strong and scattered around the country, would wake up to find the Catholic lords in a position to dictate terms, of which they had planned; full toleration of the Catholic religion, a guarantee against further confiscation of Catholic-owned land and an end to the legislative superiority of the English Parliament over the Irish one.1

So went the plan. It was an ambitious one. According to one source, they had only 40 muskets and 2 barrels of gunpowder in their possession at the outset.2 And, as is often the case, things worked out quite differently in practice.

On Friday evening, Phelim O’Neill appeared at Charlemont fort in Armagh as an uninvited dinner guest. The Governor of the fort, Caulfield, like O’Neill, a member of the county’s social elite, may have grumbled at the last minute interruption, but he nevertheless had O’Neill and his servants admitted. No sooner were they inside when they produced knives from under their mantles or cloaks and overpowered the guards. Within minutes, the castle was under their control.

Elsewhere, 18 of O’Neill’s followers seized Dungannon Castle by a similar ruse, pretending to John Perkins, the governor of the peace, that they wanted a warrant to pursue cattle thieves. Perkins was writing up the warrant when he felt a scian (knife) at his chest and was ordered to surrender the castle and its arms. O’Neill, visiting the Castle after midnight, was delighted with the coup de main. Slapping Perkins on the back he gloated, “ah you old fox, I have caught you! I am gladder to have you than Caulfield, who I have safe enough at Charlemont.”3

The northern rebels had done their part. It remained only for the seizure of Dublin for the coup to become reality. When MacGuire and O’More arrived in Dublin, however, they found that only around 80 of the 200 men they had planned for had turned up. They decided to wait one more day and in the meantime retired to a tavern. The would no doubt have spoken in Irish, but although Dublin was an English speaking city, it was not unusual for Gaelic gentlemen to stay there and they would have attracted little notice.

The northern rebels did their part but the Dublin plot was betrayed by an informer

During the night’s drinking, Hugh MacMahon happened upon his foster brother Owen O’Connolly. O’Connelly was, like McMahon, a Gaelic native of what is now county Derry. Unlike his foster brother he was also a tenant of English parliamentarian John Clotworthy and a convert to Presbyterianism. MacMahon perhaps fell to drunken boasting and revealed the details of the plot to O’Connolly.

At some point in the night, O’Connolly made his excuses and rushed to William Parsons, one of the Lords Justice (effective government of Ireland) with news of the impending putsch.

Parsons immediately had MacMahon arrested and in custody he, apparently in an attempt to frighten the English authorities into letting him go, told them of an apocalyptic rebellion that would fall on them at ten the following morning. Their followers all over the country would be out, destroying the houses of those who would not join them. They would “destroy all the English inhabitants” and, “in all the sea ports and towns in the Kingdom, all Protestants should be killed that night”.4

Some of the other leaders of the rebellion were scooped up. Conor MacGuire denied all knowledge of the affair but arms were found in his lodgings when they were searched.

The following morning, October 23rd, rumours seeped out into the Dublin streets, thronged with people and horses, come to town for the market, that rebellion and a “general massacre” of English and Protestants could break out at any moment. The drawbridge of Dublin Castle was drawn up and several times during the day, “sightings” were made of a “rebel army” trooping down from the Wicklow hills.

Nerves were not eased by the fact that the upper classes habitually went armed anyway. One gentleman, adjusting his sword and scabbard on his hip in the street, was thought to be giving the signal for rebellion, with the result that every other armed man within view drew his own weapon in trepidation. Able to stand the tension no more, that evening the Lords Justice ordered that all non-residents must leave the city within an hour on pain of death.

Under cover of a horde of, no doubt bemused, farmers and countrymen, the remaining rebels including Rory O’More slipped out of Dublin.5

The view from the top

Looked at from the top of Irish Catholic society, the rebellion was born, not for the last time in Irish history, at that point where crisis meets opportunity.

The impending crisis was the steady displacement at the top of Irish society of the Gaelic and Old English Catholic landed families who had survived the Elizabethan conquest of 40 years earlier.

The overwhelming problem here was religion. Most of the pre-Tudor landed families (owners of some 60% of the land of Ireland) had stuck stubbornly to the Catholic religion, in spite of the English Kingdom of Ireland’s official Protestant religion. James I called them “half-subjects” – prepared to give him loyalty in civil but not in religious matters.

The punishments for this were not yet grave. Failure to attend Protestant services resulted in a fine. In theory public practice of Catholicism could lead to arrest and imprisonment but in practice, Catholic priests and even Bishops were discretely tolerated as long as they kept their heads down.

But what remaining Catholic did mean was that the political power of the old landed families was seeping away. The government of Ireland – the Lord Lieutenant, his Privy Council and the Lords Justice were all English and Protestant. Catholics were excluded from these positions of “honour profit and trust” as one, Richard Bellings, complained. The Irish Parliament’s constituencies had also been altered to give Protestant a majority and by 1641, Catholics held just 70 out of 240 seats.6

The religious question also made the older Irish elite vulnerable to an acquisitive new class of colonists, known as the “New English”, though some of them were in fact Scots, who had arrived in Ireland since the Elizabethan wars. Catholic landowners were threatened with partial land confiscations, due to the questioning of their land titles.

Thomas Wentworth, the Lord Deputy of Ireland, was also in the process of planning new seizures of Catholic-owned estates in Connacht and Leinster – something that greatly antagonised the most powerful of the Catholic landed families. And yet another factor was that many Irish Catholic gentry were also heavily in debt for one reason or another. Phelim O’Neill for instance owed over 12,000 pounds to creditors in Dublin and London.7

Events in England and Scotland provided both the moment of crisis and of opportunity. King Charles I tried, between 1637 and 1640, to impose an Anglican-style prayer book on Presbyterian Scotland. The Scots in response had risen in revolt against the King’s religious policies. A state of on-off skirmishing, known as the ‘Bishops’ Wars’ ensued along the English-Scottish border over the following three years. In England the Parliament took the opportunity provided by the war with the Scots to voice their own concerns about Charles’ Catholic-style reforms and also over issues concerning Parliamentary consent for Royal rule.

Tensions between the King and Parliament in England provoked a crisis in Ireland but also gave the 1641 rebels their opportunity

With his subjects in England and Scotland in a state of semi-revolt, Charles had turned to Ireland to raise an army, promising the Catholic elite there the reforms they had been pressing for in return for their paying for a Catholic-manned army (officered by Protestants however) to put down the Scots. This created such a storm of protest in England that the scheme had to dropped and the 7,000 Irishmen mustered at Carrickfergus were disbanded.

To the Protestant English Parliament it all began to look like a huge Catholic plot, starting with the King and involving Irish Catholics. It became common in Parliament to talk of the necessity of, “extirpating Papacy out of Ireland”. England was on the road to civil war between Parliament and King over who would rule.

In Ireland this brought the plans for revolt to a head. Now the proposed coup d’etat of a handful of Ulster Gaelic gentry could be portrayed to the King as defence of his rights from the “Puritan” Parliament and presented to other Catholics as the only means of heading off a hostile invasion from England or Scotland. Indeed, no sooner had Phelim O’Neill taken those forts in the north than he produced a forged commission, claiming to be acting on the King’s behalf.

The popular rebellion

The small group who set off the rebellion on October 22-23 1641 thought it would be a minor display of force followed by negotiations. But judging from their reaction, the mass of Irish Catholics, that is the poor and landless, saw the Rising very differently.

Phelim O’Neill and his co-conspirators wanted a minor re-adjustment to place them back at the top of Irish society. They did not want to overthrow the English presence in Ireland or to throw out the Protestant settlers who had arrived since 1600. Phelim O’Neill, who was a substantial landowner in south Ulster, had recently evicted the native Irish tenants of his lands at Caledon in favour of 48 ‘British’ families, who “were able to give him much greater rents and more certainly pay the same”.8

To the Catholic Irish lower down the social scale, the Protestant settlers such as these represented an urgent threat to their livelihood. They had taken land that was believed to belong by right to the native people. They spoke a different language, they were a different religion and, above all, they were richer. The summer harvest of 1641 had been poor and a great many tenants struggled to pay their rent or simply to feed their families.

So for them, and also for those Catholic gentry who had lost their lands in previous plantations, the Rising provided an opportunity in equal parts, for social revolution and for revenge. If that was not enough, there were also some 7,000 Catholic disbanded soldiers, raised for the King’s service in 1640, on the loose.

For the Catholic elite, the Rebellion meant a show of force and then negotiation.For the mass of people, it was chance for revenge.

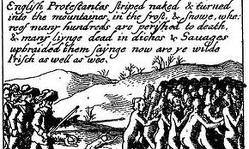

On Sunday October 24, with Phelim O’Neill’s insurgents in control of the surrounding area, the Protestant settler Henry Boine in Tyrone found himself confronted by one James Duff McDowell and a band of 40-50 men, “robbing and despoiling all the English thereabouts”.9

According to Richard Bellings, an appalled Catholic gentleman from county Dublin, “the floodgate of rapine, once being laid open, the meaner sort of people was not to be contained…rich and easy booty, taken from those seemed rather to be amazed at their loss than sensible of it”..

However, as the weeks went on, beatings and robbings turned to killings, “several innocent souls, astonished with the madness with which their neighbours among whom they had dwelt so many years so friendly were possessed, lost their lives”.10

In and around Dungannon, 22 of the unfortunate British tenants who had been settled there by Phelim O’Neill himself, were killed by the local Ui hEochaidh clan. They also murdered his prize prisoner, Lord Caulfield who had let O’Neill into Charlemont fort on October 22nd. By early 1642, some 4,000 Protestant civilians had died in the turmoil. 11

From Rebellion to War

Let’s return to Dublin on October 23rd. The Lords Justice had narrowly foiled an attempt to take Dublin Castle. Reports were starting to reach them of the rebellion in the north and of attacks on Protestant settlers. One leader of the rebellion, whom they had in custody, had told them that there was a plan to exterminate all the English and Protestants in Ireland.

They overreacted wildly and savagely. The day after the attempted coup, the Lords Justices had blamed the rebellion on, “a most disloyal and detestable conspiracy intended by some evil affected Irish Papists” and sent punitive expeditions to north Dublin and Wicklow.12

On November 1, an English commander Charles Coote, following rumours that rebels were coming south from Ulster, led a sortie to Santry, north of Dublin, where in early morning he found some men sleeping in the fields. Coote had them killed and had their heads brought back to Dublin, where they were stuck on pikes. In fact they were totally innocent farm labourers. A shocked city Alderman named Arthurs recognised one head as that of his servant, whom he had sent to check on his farm house.13

Very few of the Catholic elite had been in on the initial plot – indeed many of them thought of it as madness. Now, squeezed between, on the one hand an anarchic popular rebellion and on the other by a vengeful government, which appeared to blame all Catholics for the Rising, they, as one Catholic writer put it, “must either tender their necks unto the merciless doom of the King’s enemies or join with Phelim O’Neill…of these two evils, they chose the last being the least”.14

Ireland stood on the brink of eleven years of bloody war, the cruelty of which shocked even veterans of the Thirty Years War. One such was Owen Roe O’Neill, who in 1642 remarked, “on both sides there is nothing but burning, robbing in cold blood and cruelties such as are not usual even among the Moors or Arabs”.15

There had, in fact, been no plan to rise in the whole country and no plot to massacre Protestants. The English government of Ireland was likewise caught completely by surprise and had had no plans to “raze the name of Catholics and Irish out of the whole Kingdom” on the eve of the Rising, as the rebels claimed by December 1641.16

The Rebellion triggered 11 years of bloody war in Ireland

But in the months and years ahead, fear, paranoia and the simmering resentments that lurked just beneath the surface of mid 17th century Ireland, would help to make all of these nightmare scenarios become realities.

Listen to Cathal Brennan interview Dr Micheal O Siochru on the rebellion here.

References

[1] Padraig Lenihan, Consolidating Conquest p92-94

[2] Richard Bellings, History of the Confederation and War in Ireland (c. 1670), in Gilbert, J.T., History of the Affairs of Ireland, p7

[3] Nicholas Canny, making Ireland British, p470

[4] Bellings p9-10

[5] Bellings p11-13

[6] Lenihan Consolidating Conquest, p88

[7] Michael O Siochru, God’s Executioner, p23

[8] Padraig Lenihan, Confederate Catholics at War p31

[9] Canny p 474

[10] Bellings p 24, 32

[11] Lenihan, Consolidating Conquest p98-100

[12] Bellings p18

[13] Bellings p43-44

[14] Aphorismicall Discovery of Treasonable Faction (c. 1652), in Gilbert, J.T., History of the Affairs of Ireland, Irish Archaeological and Celtic society, Dublin, 1879.

[15]Lenihan, Consolidating Conquest p102

[16] Lenihan, Confederate Catholics at War, p22