The Crowther Family – An Irish Story

John Dorney looks the fortunes of the Crowther and Knowles families of 19th century Dublin. They were working class Protestant unionists, whose 19th century experience took them from Royal Navy orphanages to electoral battles in Dublin to the battlefields of the American Civil War.

John Dorney looks the fortunes of the Crowther and Knowles families of 19th century Dublin. They were working class Protestant unionists, whose 19th century experience took them from Royal Navy orphanages to electoral battles in Dublin to the battlefields of the American Civil War.

18th Century Dublin

In the mid 18thcentury, Dublin was considered the second city of the British Empire. It was the seat of the Irish Parliament and home to many of the Anglo-Irish elite at the top of the pyramid known as the “Protestant Ascendancy”.

Much of the city’s finest architecture dates from this period – grandiose public buildings such as the Four Courts and the Customs House and the stately homes that line, for example, Merrion Square and Fitzwilliam Street.

What is less well remembered, however, is that the city’s population at this time (and not just its elite) was also largely Protestant. In 1690, after William of Orange’s victory over the Catholic King James at the Battle of the Boyne, he was greeted as a liberator by much of Dublin’s population.

In the 1660s, Dublin is estimated to have had a Protestant majority of over 70%, but by 1800, the Protestant population had shrunk to about a third. Protestants represented a majority in the early 1700s and about 40% by the 1760s. Their total numbers were about 70,000. But while their numbers stayed static, Catholics were migrating to the city from the rest of Ireland and the city’s population was increasing – to over 200,000 by 1800.[1]

The Protestant working class in 18th and 19th century Dublin was concentrated in the Liberties area

The Protestant citizens of Dublin were not all landed magnates, such as the Duke of Leinster, whose stately home houses the modern Irish government buildings. The bulk of them were tradesmen and artisans – concentrated especially in the Liberties and Combe area, to the south and west of the old city walls, where according to historian Jacqueline Hill, “working class Catholics and Protestants lived in close proximity to each other and violent sectarian clashes had recurred throughout the 18th century”.[2]

Two such working class families were the Crowthers and the Knowles.

The Knowles can be found in and around the Liberties as far back as 1770s. The men of the Knowles family were carpenters and were, as members of the carpenters’ guild, Freemen of the city. William Knowles, a carpenter, was admitted to the Guild of Carpenters and, by dint of that, the Freemen of Dublin in 1773.[3] Knowles was also admitted as Mason in to Dublin lodge 206 in 1769.

Being guild members and freemen were small but significant advantages for Protestant families

Their status as Freemen, guild members and masons were small but significant advantages for Protestant families like the Knowles’ – giving them access to work and also the right to participate in the political world of the city.

Their other tie to the establishment was a tradition of service in the British Army and Navy. William Knowles worked refitting Royal Navy ships at the Liffey dockyards. John Crowther arrived in Dublin in the early 19th century as an infantry soldier in the British Army.

The Hibernian Marine Society

The Hibernian Marine Society

Despite their marginal privileges, the Crowthers and Knowles’ did not have things easy. In December 6 1802, Thomas Knowles, son of William, was admitted to the Royal Hibernian Marine Society – something like boarding school and an orphanage, affiliated with the Royal Navy. His parents were listed as dead.[4]

The school was, at the time, in deep trouble. It had opened in 1766, with the idea of providing some education and an apprenticeship for boys whose families could no longer take care of them. It took in boys of between 7-10, generally orphans. For the first 15 years or so, the records show that most boys were indeed apprenticed after a few years. Generally to a family or “gentleman”, sometimes in Ireland, sometimes in Britain and even in America. Others left for service in the Royal Navy. While some “eloped” or were “expelled for bad behaviour”, most saw out their time in the School.

All this changed from the 1780s onwards, the records become much more sloppy and the numbers listed as having “run way” or “eloped” shoots up. By 1794, the majority of boys taken in ran away. This continued throughout the 1790s. One boy was “forcibly removed by his parents” from the institution. The numbers “expelled” and “discharged” from the school likewise rose and numbers apprenticed fell. Whatever was happening in the Hibernian Marine Society, it was not good. The rot was not stopped until 1809, when the numbers running away fell sharply. [5]

In this respect, Thomas Knowles was reasonably lucky. He did not die in care, or “elope”. Instead he volunteered for the Royal Navy on May 24, 1805, aged 12, where he was posted to the HMS Wizard. The young orphan does not seem, however to have been strong enough to serve on board the warship. Instead he was assigned to port duties, most likely as a clerk or possibly as an armourer – he later worked as a gun smith.[6]

He returned to Dublin in 1811, where he married and started a family.

Thomas and Susanna Knowles grew up in orphanages. The next generation pulled themselves up from the ranks of manual labour

His sister, Susanna Knowles, had likewise grown up in an orphanage – most likely the Masonic orphanage for girls, though records for the period have not survived. She married John Crowther. Crowther, of Halifax in England, had also served in the Napoleonic Wars, in the 53rd Regiment of Foot in the British Army. After serving in India and spell in a French prisoner of war camp, he settled in Dublin, where he had been stationed in 1805.[7]

Life remained a struggle, however. Benjamin Crowther, one of John and Susanna’s sons, recalled in 1866 that, “I remember on information of my mother, that being in a dying state of whooping cough at the tender age of eight days, I was unable to be taken to the Parish Church to receive baptism there”.[8]

The next generation of Crowthers and Knowles managed to pull themselves up somewhat from the ranks of manual labour. John Crowther and his son David were schoolteachers and clerks. They were clearly a close-knit bunch as both extended families had their residences within a small area of central Dublin. They also habitually served as witnesses to each others’ marriages and baptisms.

Freemen of the City

The guilds of Dublin dated back to medieval times and originally regulated trade, deciding the number of apprentices to allow, the price of labour and the quality of goods. They lost this function from the 1760s onwards as trade was liberalised and as more men became freemen based on their descent from a father or grandfather.[9]

From this point on the freemen were essentially a political title, giving its 3,000 or so holders the right to hold office, bear arms and vote for Aldermen who elected a Lord Mayor. Catholics were banned from becoming freemen in 1692.[10]

So the Freemen was an institution which gave working class Protestant men (but only them) an important say in how the city was run, along with the elite.

However, by the time John Crowther and his brother-in-law, Thomas Knowles, were establishing their families, things were changing in Ireland. In 1829 Catholic Emancipation, the right of Catholics to hold office, was granted. These were years of reform in Ireland, as Catholics were granted full rights for the first time, under the administration of the Liberals in Britain and especially the Under Secretary for Ireland, Thomas Drummond.

In the years 1829-1845, Catholics got the right to hold public office, official employment was opened to them. The police began recruiting Catholics, and the Orange Order was outlawed in 1836. [11]

These were years of reform in Ireland, as Catholics were granted full rights for the first time

In addition the Protestant Yeomanry militia was disbanded in 1835, after an incident in Wexford in 1831 where they killed 14 people in a riot. Their arms were collected in 1841 – presumably to avoid violence in the election of that year.[12]

The Dublin Corporation was totally reformed in 1840, and voting was confined to property holders of 10 pounds or more. This meant that the freemen, who effectively represented working class Protestants, lost their voice in the Corporation and Protestants in general lost their control over the City government. Whereas the old Corporation was exclusively Protestant, Catholic votes now outnumbered Protestants 2:1.

In 1841 the Catholic, nationalist leader Daniel O’Connell became mayor of Dublin, the first Catholic to hold the post since 1689.[13] O’Connell, head of the Repeal Association, campaigned for Repeal of the Act of Union of 1801, which had abolished the Irish Parliament and for the return of Irish independence.

In 1841 the Catholic, nationalist leader Daniel O’Connell became mayor of Dublin, the first Catholic to hold the post since 1689.[13] O’Connell, head of the Repeal Association, campaigned for Repeal of the Act of Union of 1801, which had abolished the Irish Parliament and for the return of Irish independence.

These were times of great uncertainty for working class Protestants in Dublin, as they saw their previously (slightly) privileged status eroded. Catholics could now hold office and dispense jobs to their co-religionists. The Poor Law, where local authorities admitted the destitute to workhouses, was also reformed in 1839 so that Catholics and Protestants were treated equally and most of those elected to these bodies were now Catholics.

On top of that, there was a severe economic recession in 1839-42. Having friends in the right places was becoming more important than ever.[14]

The electorate for general elections was reduced sharply after Catholic Emancipation in 1829, from 216,000 to 37,000 as the property qualification for voting was raised from 40 shillings to £10 per year. However, one of the groups who could get around this was the freemen of the cities.[15]

The Conservatives enrolled as many Protestant freemen as possible, including the Crowthers, to increase their vote in the election of 1841

The Conservatives (who in Ireland represented the ultra-Protestant interest), starting in 1840, tried to enroll as many freemen as possible to increase their vote in the election of 1841 – including John Crowther, his sons David and William Thomas and William Knowles – son of Thomas Knowles[16]. This was the best way of enabling poorer Protestants, who almost always voted Conservative, to vote in Parliamentary elections. If they needed encouragement, the Conservatives were reputedly also paying bribes of three pounds a head to vote for them – which they could verify, as the advent of the secret ballot was still in the future.

The Liberal government in Britain attempted to remove the freemen’s right to vote but this was vetoed by the House of Lords. [17]

There was a massive increase in admission of freemen starting in 1841, as can be seen from the respective numbers of John and David Crowther. John was number 593, admitted on October 26 1841, and David Crowther, (admitted 1844) is number 3338. To give an idea of the scale of the increase, under the letter ‘c’ there were 5 new freemen in all of 1840 and 165 in October 1841 alone. [18]

The Liberals and Repealers tried to get the new freemen struck off again, but were generally unsuccessful.

In the Freeman’s Journal (A Catholic, nationalist paper, not connected with the Freemen of the City) of 1840, we find the Liberals trying to get struck off the electoral register, “the admission of fictitious votes” of, among others, John Crowther. His son David’s credentials were similarly questioned in 1844.

As a result of the freeman vote, the Catholic, nationalist leader, Daniel O’Connell lost his Westminster seat in Dublin in 1841. Jacqueline Hill writes, “among O’Connell’s supporters, there was considerable resentment against Protestants who had voted for the conservatives, especially those from a humble background who had a vote by virtue of being freemen.”[19]

The Conservatives also took a seat off the Liberals in a by-election of 1842 – again, in large part due to the freeman vote.

The Freeman’s Journal wrote bitterly that the freemen were voting, “overwhelmingly” for Conservatives. “As a class, houseless, penniless, paupers on whom the now defunct Corporation conferred that ‘freedom’, that they might make them subservient to their own dishonest purposes”.[20]

Orange Politics

Orange Politics

Richer Protestants got around the advent of Catholic political power by moving out of the city proper to new “townships” such as Rathmines and Monkstown, where they formed a majority and which elected unionist candidates all the way up to 1914[21].

With much of the city’s local government now in Catholic, O’Connelite hands, the working class Protestants of Dublin began to organise on their own behalf.

Their sense of abandonment and frustration is caught in the following complaint from the Guilds in 1843 about, “the transfer of the Corporation into the hands of treasonable Popish demagogues thereby denying the Protestant Freemen the rights and privileges conferred on them by monarchs for their proved and devoted loyalty to the British throne”.[22]

The Dublin Protestant Operative Association (DPOA) was founded in March – April 1841, by an evangelical Church of Ireland Reverend named Tresham Gregg, to, “reverse the decline of the Protestant cause, reverse the concessions to Popery and the to defend the Union between Ireland and Britain”. ‘Operative’ here means ‘manual worker’ –this was a working class organisation and richer Protestants seem to have had little enough sympathy for them.[23]

The Crowthers appear first in the Dublin Protestant Operative Association and then in the Orange Order

David Crowther appears in the Freeman’s Journal, as the chief secretary of this group, handing a petition to a meeting of the Repealers, opposing the reversal of the Union.

The DPOA is thought to have had 500 or so members but could attract up to 2,500 people to its meetings.[24]

Their main activity was to hold rallies and to collect signatures for petitions against Catholic advances and against Repeal of the Union. A major plank of their activity was to urge all Protestants to stand together and not join the Repealers or nationalists.

Catholic Repealers in the Liberties area (the most Protestant working class district of Dublin, where the Crowthers and Knowles lived) sometimes tried to physically disrupt their meetings and also organised boycotts of their businesses.[25]

The DPOA dissolved itself in 1848, only two weeks after a meeting the Freeman’s Journal reported on, where David Crowther seconded a motion by Tresham Gregg to oppose the Repeal of the Union. It advised all its members to join the Orange Order, with which it had a close relationship. “to stand together and oppose revolution and Popish aggression”.[26]

The background to this was the planned uprising of the nationalist Young Ireland movement. The rebellion never really got off the ground but the Orange Order (legalised in 1845 by the Conservatives) mobilised to oppose it.

Sure enough, we find David Crowther in November 1849 as Deputy Grand Secretary of the Orange Lodge in Dublin[27].

At the last meeting of the DPOA, Tresham Gregg outlined the thinking of this generation of proletarian Dublin unionists and his speech is worth quoting at length. “Some Protestants”, the Freeman’s Journal quotes him as saying, “declared for Repeal of the Union, “Is there anyone present who believed that the British Constitution or Empire would be maintained if the Union were Repealed?”

Theirs was very much a politics of looking after their own. Gregg conceded that, “a demand for Repeal of the Union was put forth by a large majority of the people of this country”, they did not deny that in wake of the Great Famine, still raging in the countryside, Ireland was, “victimised by enormous evils”, though, “of a social not a political nature”.

Gregg urged Irish Protestants to “stand together” but they would ultimately lose the battles over Catholic control over Dublin Corporation

His case was rather straightforward. Before the Union, Protestants had dominated the Kingdom of Ireland, post-emancipation, this would no longer be the case. A new Irish Parliament would be Catholic-dominated and now Protestants would be cast in the role of second class citizens.

“Just look at the little Corporation of Dublin…there was not a single case of a Roman Catholic constituency returning a Protestant”. He did not “blame the Catholics for it was their duty to return their own party if they could” and he “admired their firmness in maintaining their principles”. A Repeal of the Union, he argued would inevitably lead to war between Catholics and Protestants.[28]

Seeing this kind of language, “Orange against Green”, “The Empire” against “Irish Freedom”, the Irish reader will no doubt brace themselves for the sound of gunshots. However it never quite came to that in 1840s Dublin. Rival Repeal and Unionist speakers attended each others meetings and debated the issues.

While they were often greeted with “groans and hisses” and cries of “put him out”, physical violence does not seem to have been a feature of popular politics in the city. Tresham Gregg told his followers, “brother Protestants and Orangemen”, to “preserve order and bear with those who disagreed with them”, “but indecent disorder would not be tolerated”.[29]

The battles over Catholic political power and defence of the Union were ones which the Protestant unionists in Dublin would ultimately lose, in the 19th and early 20th centuries. That this was done peacefully was in large part due to the  emigration of many working class Protestants from the city.

emigration of many working class Protestants from the city.

In America

David Crowther and his brother Benjamin were two such emigrants. Both made their way across the Atlantic, seeking new opportunities in the United States. Benjamin left in 1848 and David followed in 1855.

Benjamin later recalled in 1866, “I was unconscious then until now that the law of England required of her subjects leaving there for the United States, should first obtain a passport, nor was it ever required of me to be produced by the United States authorities on my arrival or at any other time”.[30]

Interestingly enough, the Crowthers, previously members of the Church of Ireland, became Methodists in America.

David Crowther set himself up in Brooklyn, New York, where the 1860 census shows him living in Brooklyn with his wife and three daughters, Lydia, Rachel and Charlotte and working as Law Clerk. [31]

Benjamin Crowther penetrated much further west, 1000 miles, to the frontier state of Missouri, where he established a farm with his wife Minerva Lilly, originally of Baltimore, Maryland, with whom he had four children.[32]

The old quarrels were not left behind in Ireland, David Crowther was involved in a violent sectarian confrontation in Brooklyn in 1860

The old quarrels were not left behind however. Irish Catholic, as well as Protestant, immigration to America in this period was huge, particularly to the eastern cities such as Boston and New York and on the same page of the census as David Crowther in Brooklyn, well over half those listed were born in Ireland.[33].

Perhaps Crowther retained combative attitudes towards Irish Catholics from his days as a Dublin Unionist and Orangeman. Immigrants of a nationalist bent had also established the Irish Republican Fenian Brotherhood in New York in 1858, dedicated to the use of force to secure an independent Ireland, so perhaps hard words and worse were exchanged in the buildings and streets of immigrant Brooklyn.

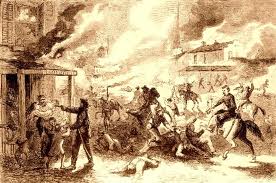

Whatever the reason, in 1860, Crowther appears in a violent dispute with a neighbour named McCormick, a 50-year-old Irish labourer living in the same building in Brooklyn New York.

The Brooklyn Eagle of 26 September, 1860, reports, “One roof shelters the Crowther and McCormick families, no 65 main street, and between them a feud of long standing exists…McCormick as good as swore to have Crowther’s life and let , ‘the Orange blood out of him’: With this intent, on Saturday the 18th of August, he tried to force his way into his apartment, which if he had done he would have had a good chance of being shot, as David, armed with a loaded pistol, was inside prepared to defend the sanctity of his home altar and fireside.”

Nor was that the end of the matter. On September 14, “the bloodthirsty McCormick”, “ejected” Crowther’s wife and children from their home. Crowther must have then gone to the authorities, as by September 26th, McCormick was before a Justice Cornwell.[34]

Perhaps as a result, David Crowther sent his daughters far away to live with his brother Benjamin in Missouri where, in 1860, Benjamin Crowther listed them as being born in England. [35] Fortunately enough, the girls were back in back in New York by April 1861, when the American Civil War broke out. The conflict would divide the two Crowther brothers permanently.

During the Civil War, David help build the ships (including the USS Monitor) at the Brooklyn Navy Yard. In 1864, he was called upon to give a speech to the 64th Infantry regiment where he said, “as an Irishman I feel proud of the honour conferred on me in being permitted the privilege of bearing my testimony to the great cause…to uphold and maintain the Union of the United States…and that these broad stripes and bright stars may speedily wave triumphantly over the ruins of secession and the grave of rebellion.”[36]

During the Civil War, David help build the ships (including the USS Monitor) at the Brooklyn Navy Yard. In 1864, he was called upon to give a speech to the 64th Infantry regiment where he said, “as an Irishman I feel proud of the honour conferred on me in being permitted the privilege of bearing my testimony to the great cause…to uphold and maintain the Union of the United States…and that these broad stripes and bright stars may speedily wave triumphantly over the ruins of secession and the grave of rebellion.”[36]

Crowther, had, no doubt, through his years in various organisations in Dublin, learnt to play the political game. Judging by his description of his himself as an “Irishman”, he may already have dispensed with the enmities of Orange and Green. In the 1880s he became Recording Secretary of the Republican Party in the 19th Ward in Brooklyn, and even tried to use his political connections to become the Chief Clerk (most senior civilian civil servant) of the US Navy Shipyard at Brooklyn.

Benjamin Crowther became an ardent Confederate after his house and farm in Missouri were burned by Federal troops

Although David was very much a Union man in the US, his brother, Benjamin in Missouri, was a Confederate cavalry soldier.[37] So committed was he to the Confederate cause, that after the South’s defeat in the Civil War, he followed Confederate General Shelby to Mexico rather than live under the Union again.

Behind his ardent Confederate politics lay his experience of the bitter guerrilla war in Missouri. According to a letter to the British Embassy in Mexico, federal troops had burned his home and farm after he had refused, “to take the oath of allegiance to the United States Government (so called) and to perform such duties as might be prescribed to him by the military authorities”.

In the letter, he described his Confederate service as, “the solemn duty I owed to almighty God, my British origin and my pious mother…my wife children and property, forcibly to destroy a wicked, cowardly and fanatical vandal horde who knew more practically about the art of houseburning robbery and cold blooded murder than they did of the art of war, or of human gallantry, or of any form of government free from being mob rule.”[38]

Benjamin Crowther died by drowning in Tuxpan, Mexico in 1872. His wife brought the family back to the United States and settled in San Antonio, Texas.[39]

An Irish Story

And so ends this Irish story. Benjamin Crowther in his letter, made no mention of any Irish origins. The Crowther girls, listed in the 1860 census as being English, had in fact been born in Dublin in the 1840s and baptised in St John’s Church, to a family long-resident in the city.

From now on though, their descendants would simply be Americans.

The Crowthers of Dublin do not conform to the stereotypes of Irish-Americans but they too are part of the Irish story

James Crowther of San Antonio Texas, who began researching his family history in the 1980s, had, prior to 2010, no idea that his ancestors had originated in Ireland – nor had his father or grandfather.

One is struck by the contrast with the stereotypical Irish American – proud of their Catholic, rebellious heritage and clinging to an idea of “Old Country”.

But the Crowthers of Dublin are also part of the Irish story. They were part of a soon-to-vanish working class southern Protestant unionism. They fought to maintain the small scale privileges they had had in Irish society, but ultimately, they lost.

In seeking a new life America, they ultimately rejected the land of their birth in favour of a future life in their new home.

Bibliography

Primary Sources

*Royal Hibernian Marine Society, Record of Boys, Trinity College MSS, 5202 a, b & c

*List of the Freemen of the City of Dublin, Volume 6 & 7, Dublin City Library.

*US Federal Census, 1860.

*Brooklyn Eagle

*Freeman’s Journal

*Church of Ireland Baptismal Records

*Benjamin Crowther to the British Embassy of Mexico, 23 February 1866

*Memoriam of Minerva Ann Crowther, November 17, 1903.

Secondary Sources

*Blackstock, Allan, An Ascendancy Army, The Irish Yeomanry 1796-1834, Four Courts, Dublin, 1998.

*Hill, Jacqueline From Patriot to Unionists, Dublin Civic Politics and Irish Protestant Patriotism 1660-1840, Clarendon, Oxford 1997.

*Hill, Jacqueline, The Protestant Response to Repeal, the case of the Dublin working class, in Ireland Under the Union, (Lyons and Hawkins eds), Clarendon 1980.

*Hoppen, Theodore K, Ireland since 1800, Conflict and Conformity, Longman 1995.

References

[1] Jacqueline Hill, From Patriots to Unionists, p20

[2] Hill, Protestant Responses to Repeal, the Case of the Dublin working class, p42.

[3] List of the Freemen of Dublin Volume 7

[4] RHMS, Record of Boys Trinity MSS 5202 B

[5] Ibid, Vols A, B and C

[6] Information from James B Crowther.

[7] Information courtesy of JB Crowther.

[8] Letter from Benjamin Crowther to the British Ambassador of Mexico, 23 February 1866.

[9] Jacqueline Hill, from Patriots to Unionists, p25-27

[10] Hill, Patriots to Unionists, p28

[11] Hoppen, Ireland since 1800, p21-24

[12] Blackstock, an Ascendancy Army, the Irish Yeomanry, pp251, 295

[13] Hill, Protestant Reponses, p46, Though the British Government appointed boards retained control over policing, paving, cleaning and lighting.

[14] Hill, Protestant Response to Repeal, p42-44

[15] Hoppen, Ireland since 1800, p18

[16] Freedom Rolls of Dublin, Vol 7 1841-1865

[17] Hill, Protestant Response to Repeal, p 45

[18] Rolls of the Freemen of Dublin, Vol 6 and 7

[19] Hill Protestant Response p44

[20] Hill, Protestant Response, p379

[21] Hill, Patriots to Unionists, p382

[22] Hill, Patriots to Unionists p 383

[23] Hill, The Protestant Response to Repeal p36-40

[24] Ibid. p50-51

[25] Ibid p54-55

[26] Ibid. p64

[27] Freeman’s Journal, 3 November, 1849

[28] Freeman’s Journal 27 April 1848

[29] Freeman’s Journal 27 April 1848

[30] Benjamin Crowther to British Embassy of Mexico, 23 February 1866.

[31] US Federal Census, 1860 p 27

[32] In memoriam, Minerva Ann Crowther, 17 November 1903

[33] US Federal Census, 1860 p 27-28

[34] Brooklyn Eagle, 26 September 1860.

[35] List of the Free Inhabitants of Fort Osage, Jackson County, Missouri, 23 July 1860.

[36] Brooklyn Eage, 5 March 1864.

[37] Information from James B Crowther

[38] Benjamin Crowther to British Embassy in Mexico, 23 February 1866.

[39] Memoriam of Minerva Ann Crowther, November 17, 1903.

Note: This article started as a research project for James B Crowther. My thanks to him for introducing me to his family history for his help and guidance with sources.