Peter Hart – A Legacy

Peter Hart passed away in late July 2010, aged just 46. We here at The Irish Story extend our condolences to his family, partner and friends. Here, John Dorney tries to evaluate his life’s work.

Peter Hart passed away in late July 2010, aged just 46. We here at The Irish Story extend our condolences to his family, partner and friends. Here, John Dorney tries to evaluate his life’s work.

Perhaps more than other historian who has worked on modern Irish history, Peter Hart found himself at the centre of furious and sometimes vicious debates over his use of sources, arguments and conclusions.

Readers looking for a dissection of such debates here, such as that between him and Meda Ryan over the ambush at Kilmichael, or the killings at Dunmanway in April 1922, will not find them in this review. They are better covered on their own elsewhere; in Seamus Fox’s excellent article on the Kilmichael controversy and my own take on the Dunmanway incident here.

This is an attempt to look at Hart’s work in total, to appreciate its strengths, suggest its weaknesses and evaluate its importance.

In fact, a major gap in the public debate over Hart’s writings is the concentration on a few micro episodes in his work. So, as an attempt to redress the balance, this is an attempt to look at Hart’s work in total, to appreciate its strengths, suggest its weaknesses and evaluate its importance for our understanding of what Hart called the Irish Revolution, of 1913-1923.

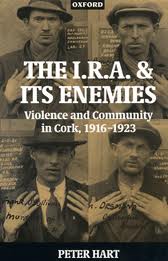

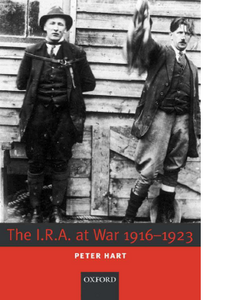

To do this, two of Hart’s books will be considered, The IRA and its Enemies – Violence and Community in Cork, 1916-1923, and The IRA at War, 1916-1923.

Social base of the Volunteers

Hart’s analysis of the Volunteers or IRA was based on an extensive statistical trawl through things like casualty reports, arrests sheets and prison records.

What he found was that the average Volunteer in county Cork was young, typically aged 23-26, single, usually of modest background, but rarely of the poorest classes. They described themselves with expressions like “plain men”, “decent people”, “ordinary fellas”, “respectable people”. Towns were over-represented and farmers sons were under-represented. Almost all Volunteers were Catholics.[1]

According to their perspective, Hart writes, the real patriots were to be found in working poor, small farmers and “mountainy men”. The businessmen and landowners were loyalists, the bigger farmers and middle classes sold out the Republic with their support for the Treaty in the Civil War.[2]

An important feature of Hart’s work is the stressing of the twin features of maleness and youth among the Volunteers of 1916 to 1923. To them, Hart argues, Irish Freedom also meant personal freedom, a chance to escape the rigid parental, social and Church control of early 20th century Irish society and to assume a position of power usually denied to young men.[3]

This is an important insight and found in the accounts of many IRA veterans. Ernie O’Malley described his career in the IRA as, “a sheltered individual, drawn from the secure seclusion of Irish life to the responsibility of action”.[4]

This is an important insight and found in the accounts of many IRA veterans. Ernie O’Malley described his career in the IRA as, “a sheltered individual, drawn from the secure seclusion of Irish life to the responsibility of action”.[4]

Mossie Hartnet, a Limerick Volunteer, told in his memoirs of the possibilities for a young IRA man of turning of the tables on a tyrannical older generation. For example when an 18-year-old IRA man stuck up a post office for funds and the postmaster, previously, “rude and domineering” to the young men of the district, “became most obsequious” to the gunman, his nephew, who “who he titled ‘sir’ in a frightened and subservient manner”.[5]

Hart’s case study of the social profile of Cork Volunteers has not always been replicated by studies of the IRA in other places. A survey of county Galway, for example, found that the Volunteers there were overwhelmingly rural and farmers’ sons.[6] However, the picture of the IRA as a young, lower middle class or “respectable” working class organisation is largely borne out elsewhere. The IRA saw themselves as the sons of the Irish nation, but not necessarily as representatives of any one class.

Hart did not see social questions as being at the heart of the revolution

Nor did Hart see social questions as being at the heart of the revolution. He writes, “this is not to say that nothing happened in terms of social unrest, or that nothing important happened, but rather that nothing revolutionary happened”.[7]

Other authors have disagreed and historians, such as Fergus Campbell and Conor Kostic, would place strikes, land occupations and mass action back at the centre of the revolution. However, studies of the Volunteers themselves, especially in the recollections collected by the Bureau of Military History, tend to support the thesis that the soldiers of the revolution saw it primarily in terms of Irish, not working class, freedom.

An IRA ideology?

Hart’s look at the IRA in Cork shows that the Volunteers were not necessarily more ideological that the rest of the nationalist population, not in 1918 at any rate. They believed that Ireland had long been oppressed by Britain and wanted independence. “Opposition to martial law, military recruitment and conscription as well as dissatisfaction with John Redmond’s Irish Party.”[8] This was not terribly different from what the majority of Irish nationalists believed by 1918.

Hart argues that Catholic, particularly Christian Brother, education was partly responsible for their world view, “in trying to create patriots they created gunmen”. But again, many more shared this education than served in the IRA. The Volunteers were, in a real sense, armed representatives of nationalist Ireland. However, what initially drew the fighters into the Volunteers were networks of friends and family, strong bonds of comradeship and loyalty which were much more important than ideology.[9]

Networks of friends and family, strong bonds of comradeship and loyalty which were more important in Volunteer mobilisation than ideology

However, if many Volunteers started out relatively unburdened by ideology, this did not last. Joining and fighting in the IRA changed their attitudes and their perception of themselves.

If there was an IRA ideology, Hart summed it up like this, the Volunteers were not, “a party militia or a militia party” like say, the Bolsheviks’ Red Guard or the fascist “shirt” movements.[10] They saw themselves as soldiers of the Army of the Irish Republic, above mere “politics” and somewhat scornful of it, sworn to uphold the Republic against all enemies foreign and domestic.

Hart did not accept the view that British repression and arrest of Sinn Fein activists after their election victory in 1918 was decisive in launching the guerrilla war of 1919-1921. Militant Volunteers, he writes, actually feared a turn to moderation among Sinn Fein. “The early shootings in Munster and Dublin in 1919 did not have the backing of Sinn Fein or ‘the People’, and were not intended as an armed protest against denial of recognition or negotiation. They were meant to prevent just such a turn to politics”.[11]

Hart writes that the outbreak of the Civil War can largely be understood in these terms – that of republican soldiers attempting to face down moderates and politicians. The Anti-Treaty IRA saw themselves, much as the Volunteers of 1916 did, as a citizen soldier force, to be kept in being to safeguard the Republic against weak-hearted “politicians”. Many Republicans therefore saw the Civil War as a defensive reaction on their part to the Free State’s attack on the Republicans in the Four Courts. “Theirs was a deterrent posture, not an aggressive one…to maintain their position as a standing army and to keep the Free State at bay”.[12]

For Hart, the IRA saw themselves as soldiers, above the political process, but not anti-democratic

(On this topic; a review by John Regan of the IRA at War and Hart’s response).

Geography of Revolution

Why did some areas do so much more fighting than others? Cork for instance, had a guerrilla war of considerable intensity, with over 500 dead and over 1,000 wounded in 1920 and the first half of 1921. A quiet county like Galway saw only 72 killed or injured.[15] Similar things can be said about the Civil War, which was bitterly fought in Kerry, but relatively non-existent in Westmeath. Why this was is a question that has puzzled many historians.

Hart in The IRA at War, tries various statistical correlations to try to establish why some counties or regions were so much more active and more violent than others. Intriguingly he found that the correlation between political, Sinn Fein activism and IRA operations was not that strong. Sinn Fein was strongest in the north midlands and west but the IRA’s stronghold was in Munster.[16]

Nor was it the prevalence of things like GAA clubs or Gaelic league branches – these, Hart writes, were important in mass mobilisation but not necessarily for the intensity of violence. Arms were irrelevant since most arms were captured from the British anyway, it was the will to capture them that was necessary. Terrain was mostly irrelevant for the same reason.

Hart tentatively suggested the level of police presence and the local traditions of militant activism as explanations for the geography of the War of Independence

Hart tentatively suggested a number of explanations. First, counties which had a low ratio of effective policing and courts to population saw more violence than heavily-policed counties in the War of Independence. Secondly areas with strong traditions of communal activism and militant action dating back to the Land League of the 1880s and before them the secret societies like the Whiteboys or the Defenders, tended also to produce IRA columns in the 1920s.[17]

Thirdly, the violence had a dynamic of its own once it got started. Areas with an early start to the War of Independence developed this dynamic sooner.

This is a major theme in Hart’s work. The violence of the War of Independence was cyclical. And this applied to both sides – both the IRA and the British/RIC on the ground were motivated at all times by a desire to “hit back”, and repay the local enemy for the last attack.

It is possible, according to this interpretation, that areas like Mayo, Sligo and Kilkenny were only gearing up for the fight when the truce arrived in July 1921, and if fighting had not ended, would have developed a comparable cycle of violence to the heartland of the conflict in south and west Munster. [18]

Guerrilla Warfare

This brings us into controversial territory – Hart’s writings about the nature of violence and armed action during the Irish Revolution.

One of the great strengths of Hart’s work is his compilation of statistics. From his figures on the conflict, especially in Cork, but also in all of Ireland, Hart proposed several important and influential ideas.

Firstly, regarding chronology, Hart found that not much differentiated 1919 in terms of violence from 1918, instead dating the chronology of the war of Independence from an “IRA offensive” in January 1920 to the truce of July 1921.

Furthermore, while he makes the point that the twin peaks in terms of deaths are indeed 1920-21 and July 1922 –April 1923, conventionally seen respectively as the War of Independence and Civil War, political violence was a constant throughout the period and the “truce” of early 1922 was actually one of the most violent periods in what became Northern Ireland. [19]

He found that in the War of Independence in Cork, most casualties were killed while unarmed and unable to defend themselves.

Secondly, Hart had provocative things to say about the character of violence. Firstly, he found that in the War of Independence in Cork, only between 56% (1920) and 35% (1921) of casualties were inflicted in combat; that is in fighting between armed adversaries. The remainder were killed while unarmed and unable to defend themselves. [20]

Moreover, in Cork, a third of the victims of the War of Independence in the county were civilians, targeted as informers or in reprisals by both sides. He contrasts this with the Civil War, where some 70-90% of the, considerably lower, casualties in the county were from combat and a considerably smaller proportion were civilians.[21]

Hart attributes the difference in the two phases to the “pervasive ethnic friction which so exacerbated the war against the British [being] largely absent from the Civil War”.[22]

According to Hart, The War of Independence, especially in 1921, saw a “turn to terrorism” by both sides, as fatal shootings went up but deaths in combat fell – in part due to the strengthening of the British forces and the IRA’s shortage of ammunition – but also due to the increasingly stark communal and sectarian nature of the violence.

There are two important arguments that emerge from this. One is that the conflict, while it did see many ambushes and fire fights between combatants, should not understood primarily in these terms. Hart was critical of what he called “ambushology” where the conflict is presented as a litany of periodic ambushes. Much more common, particularly as the conflict went on, he writes were assassinations and reprisal killings and burning of property.

This may look in one way as a resurrection of the old British characterisation of the IRA as a “murder gang” rather than combatants who “fought fair”. And here, as in many other instances, Hart is not helped by his sometimes airy tone, “the reality behind the myth of battle was that most planned ambushes never made contact with the enemy and most operations were aimed at one or two ‘enemies’ and had little to do with combat”.[23]

The idea that the War of Independence saw more assassinations than ambushes is borne out by other local studies.

However, Hart is clear that the description applies equally to both the crown forces and the IRA.[24] Moreover, the idea that the War of Independence, as it went on, saw more assassinations and less “fighting” is borne out by other local studies.

In Clare for instance, in 1921, the IRA killed some 30 people. Six of these were RIC men killed in an ambush in January, and six more killed piecemeal in further ambushes. The remainder were targeted shootings or executions. Similarly, out of 24 IRA men killed in the county in 1920-21, only five were killed in action whereas 11 were shot while unarmed by Crown forces.[25]

In Clare for instance, in 1921, the IRA killed some 30 people. Six of these were RIC men killed in an ambush in January, and six more killed piecemeal in further ambushes. The remainder were targeted shootings or executions. Similarly, out of 24 IRA men killed in the county in 1920-21, only five were killed in action whereas 11 were shot while unarmed by Crown forces.[25]

In Longford, four policemen were killed by the IRA in 1920, but 12 in 1921, only four in combat, along with seven civilian informers.[26] While in Monaghan, the IRA killed just three people in 1919-1920, but 18 in the first six months of 1921, of whom half were civilians, and of the remaining Crown forces, only two died in exchanges of fire rather than assassinations[27].

However, a weakness of Hart’s interpretation, I feel, is a failure to put this in context. The grim realities of asymmetric warfare meant that combat of guerrillas against armed police or troops was almost always fleeting and small in scale. Unless the lightly armed Volunteers achieved surprise and temporary superiority in numbers, it was also unlikely to cause many casualties.

Assassinations of selected people, on the other hand, almost always killed or badly wounded unsuspecting, unarmed victims. Similarly, the British forces were rarely able to corner large numbers of IRA men in combat, but to hit back at their unseen tormenters, they could always arrest and shoot a local suspect or burn the homes of his relatives.

Moreover, the idea that this did not happen in the Civil War is not necessarily borne out by the evidence outside of Cork. In fact the intra-nationalist conflict produced just as many reprisals, if not more, against prisoners or disarmed combatants in places like Dublin, Kerry and Sligo as did the struggle against the British.

Hart acknowledges this in the IRA and its Enemies but perhaps in his effort to advance his thesis of the period as one of primarily “ethnic conflict”, he downplays the bitterness of the Civil War.

It is true though, as other recent studies have shown, that in 1922-23, in sharp contrast to 1920-21, such reprisals hardly ever targeted civilians.[28] One has to agree that the absence of a British-versus-Irish and Catholic-versus-Protestant element to the latter conflict was largely responsible for this.

Another convincing argument is Hart’s model for the contrast in the “trajectory” of violence in 1920-21 and 1922-23. In the former, the War of Independence, the number of fatalities started small and escalated steadily right up to the Truce. In the case of the latter, the Civil War, casualty rates flared up in the summer and autumn of 1922, but fell sharply thereafter and slowly fizzled out by mid 1923.

Sectarianism

This brings us onto the second, and by far the most controversial, argument that Hart made about the nature of violence in the War of Independence.

This is that it was essentially an ethnic conflict, part of the “unmixing of peoples” after the First World War and comparable in character, if not in scale, with contemporary wars and population displacement in such places as Greece, Turkey and Armenia. [29]

Hart’s argument is that in Cork and in many other parts of Ireland, north and south, there was a communal, religious divide between Catholic nationalists and Protestant unionists. Protestant republicans, Hart writes, were an eccentric rarity.

“The sectarian division in Irish politics and society and the revolution’s central organising principle of Catholic/nationalist ethnicity (along with the role of Protestantism in unionism), inevitably structured the revolution north and south”.[30]

Hart argued that communal or “ethnic” conflict was central to the Irish Revolution

The IRA, in this context represented a, “quasi millenarian idea of a final reckoning between settler and native”, going back to the 17th century plantations. [31] For this reason, he describes the targeting of informers by the IRA in terms of reprisal shootings of “enemies”.

Hart notes that in killings of alleged informers in Cork, Protestants and also other “enemy” groups like ex-soldiers, travelers and beggars (outside the “respectable” nationalist community) were over-represented. He argues that this was not because of evidence against them, but simply that when IRA members on the ground said “informer” they really meant “enemy”. “It was not merely (or even mainly) a matter of espionage, spies and spy hunters, it was a civil war between and within communities”.[32]

Taken together with the killing of some thirteen Protestants in west Cork over two nights in April 1922 (apparently in response to the fatal shooting of an IRA officer) that sparked a flight of several hundred Protestants from the area, Hart argued that communal conflict and even “ethnic cleansing” was at the heart of the revolution. “Protestants had become fair game because they were seen as outsiders and enemies, not just by the IRA but by a large segment of the Catholic population as well.”[33]

One wonders, at times, if Hart, a scholar from Canada with no Irish roots, realised how explosive a proposition this was in Ireland in the 1990s. People were still dying in Northern Ireland at the hands of an organisation calling itself the IRA, regarding itself as the same organisation as that of the 1920s and still arguing that it represented all the Irish people, regardless of religion, against British imperialism.

Its unionist opponents painted it as a sectarian Catholic murder gang and its southern enemies liked to distance it from the supposedly “clean fight” the “Old IRA” had fought in the 1920s.

It is not difficult to see how Hart’s argument about the 1920s could be fitted into a unionist narrative, but it tended to undermine very dearly-held ideas that Irish nationalism and republicanism had about itself

It is not difficult to see how Hart’s argument about the 1920s could be fitted into a unionist narrative, but it tended to undermine very dearly-held ideas that Irish nationalism and republicanism had about itself – that it was at heart non-sectarian, that its struggle for independence had been heroic, that it was not a Catholic mirror-image of northern unionism.

Historical debate can rarely really be separated from the present, even less so in Ireland than in most other places. However, talking strictly about the 1920s, was Hart right? Should we see the 1913-1923 period as primarily one of communal conflict, effectively one long Irish civil war?

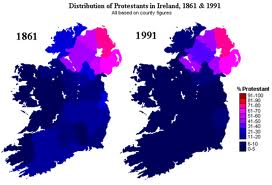

Firstly, looked at very broadly, the result of the revolution was the partition of Ireland between two states, one primarily Catholic and nationalist, the other Protestant and unionist. This is unsurprising given the very long-standing and deeply rooted sectarian divisions.

There was also some population exchange between the two states. Some 40,000 Protestants left the Free State (though probably a small proportion of these were forced out by violence) and several thousand Catholics fled violence in Belfast to the Free State, though many of them subsequently returned to the Catholic enclaves in the north.

While the scale of this was very small by the standards, for example, of the contemporary Armenian genocide, or “population exchange” in the wake of the Greco-Turkish war, it is unrealistic not to see some sectarian or communal aspect to the revolution.

On the other hand, one is immediately struck by some glaring inconsistencies to this thesis.

The first cabinet of the Free State included an Ulster Protestant, Ernest Blythe and the first President of Ireland under the 1937 constitution, Douglas Hyde, was also a Protestant. Moreover, the southern revolution was finished with predominantly-Catholic nationalists fighting each other over a point of ideology. A straightforward model of sectarian conflict does not help us understand this.

Looking, as Hart did, at the ground-level experience we must be aware of nuances. Other local studies, in large part inspired by, or at least in reaction to, Hart’s work, in Longford, Monaghan, Cork city and Clare, have not, in general, supported the thesis of random killing of Protestants as one of the primary features of the conflict.

Certainly had the IRA wanted to systematically target groups like Protestants and ex-soldiers, they did it very inefficiently, killing less than two hundred civilians out of hundreds of thousands of potential, “soft targets”.

Rather, other studies have found that the IRA really did believe they were shooting people as informers, who were actively helping the British forces. Perhaps the evidence was not always there to support such accusations but the IRA does not seem to have indiscriminately shot “enemies” in reprisal for its own reverses.

The IRA did not shoot civilian “enemies” indiscriminately but did tend to believe that ex-soldiers, Protestant loyalists and indeed “tinkers and tramps” were informers.

However this does not entirely discredit Hart’s argument. The IRA certainly seem to have been more likely to believe that ex-soldiers and Protestant loyalists and indeed “tinkers and tramps” were informers, than, for instance Catholic priests.

In Kerry for example, local IRA officer Tom McEllistrim shot a local tramp as a suspected informer simply because he was seen talking to a British officer. Another Volunteer, Tim Kennedy had two ex-servicemen shot for spying. But when confronted with evidence that a local priest was informing, Kennedy said, “I would submit myself to be put against the wall myself before I would do my ‘duty’ on a priest, no matter how bad he was”.[34]

No such restraints applied to the shooting of Protestant clergy suspected of informing, as evidenced by the shooting of one Reverend Harbord, one of ten Protestants shot over April 27-28 1922 in west Cork – apparently as suspected informers.[35]

Moreover, as the British forces directed collective reprisals against republican supporters, in the form of house burnings in 1920 and 1921, the IRA responded by burning loyalist homes. Tom Barry for instance, in reprisal for the burning of republicans’ homes in west Cork, “burned to the ground in that district all the British loyalists houses”[36].

There is also evidence of widespread lower level harassment of Protestant loyalists – raiding their homes for arms and vehicles for instance. Mossie Hartnett wrote of raiding a Protestant church in Limerick at the start of the Civil War in July 1922 and seizing six cars from the churchgoers. “It was not a nice thing to do but at this time we thought the Protestants were our enemy and on the side of the Free State”.[37]

While the Volunteers may have argued that they targeted only political enemies, to those Protestants who believed that their loyalty lay to the British state, or even the Free State, and among whom the IRA naturally looked first for informers, the distinction must have seemed a fine one.

Ultimately communal violence in Ireland was too small scale and too selective to really compare it to mass ethnic conflicts

In summary any account of the War of Independence must incorporate the role of sectarianism, which was everywhere an undercurrent to the violence. But in the south at least, it was too small scale and too selective to really compare it to mass ethnic conflicts or to explain it as one of the primary features of the conflict.

At times Hart acknowledged that the Republicans’ ideology was actually a brake on sectarianism, while at the same time he seemed to regard it as an atavistic expression of Catholic communal rage. “Republican organisations were officially non-sectarian and this played an important part in dampening down southern ethnic violence, though the IRA were its main practitioners”.[38]

One description of Anti-Treaty fighters in Cork towards the end of the Civil War, for instance, “A few stubborn groups of rebels remained at large and active, shooting suspected informers, and British soldiers, holding up mailmen, robbing post offices and harassing Protestant farmers”[39]. One has to question if this fairly represents the actions of guerrillas, who were fighting against an avowedly nationalist, primarily Catholic, National Army, on whom they inflicted the vast bulk of their casualties.

North and South

Hart’s work on sectarianism in the conflict should not be caricatured however. In a consideration of the differences between the North, and particularly Belfast, from the South in 1920-1922, he wrote of qualitatative differences between minority experiences north and south. More so than anywhere else, there were hundreds of sectarian killings and thousands of expulsions here in the North, disproportionately of Catholics.

Hart wrote that either in relative or absolute terms, northern Catholics were far worse off than their southern Protestant counterparts

Hart was aware of this, writing, “In the south, the 300,000 strong Protestant community lost 100 [civilians] killed …In the north, the 420,000 Catholics suffered well over 300 civilian deaths…so either in relative or absolute terms, northern Catholics were far worse off than their southern Protestant counterparts”.[40]

Moreover, in the IRA, “despite the violence, there was no plan, no ideology, no institutional support for continental-style ethnic cleansing”.[41]

In the north things were different. Hart writes that, “the new [Free State] regime refused to recognise the victimisation of Protestants past and present and therefore did nothing specifically to counter it”.

But in the North, “a lot of anti-Catholic violence was perpetrated by members of the security forces” and, “many of their [unionist] leaders and activists, including Edward Carson encouraged violence and discrimination”.[42]

He wrote that someone else must have the “unenviable job” of researching loyalist paramilitaries, “who operated almost exclusively as avengers and ethnic cleansers”.[43]

However, he disputed the idea that Belfast Catholics suffered a “pogrom”, the violence was not as one-sided as that, “more resembling a miniature civil war”. What was more, he writes that whereas the Protestant population of Cork dropped by 34%, the Belfast Catholic numbers fell by only 2% in this period. [44]

However, in framing the War of Independence as a sectarian or “ethnic” conflict, Hart sometimes tended to equate the experience of Belfast Catholics and Cork Protestants as minority groups targeted as internal enemies in times of conflict. The numbers alone, as well as much more indiscriminate selection of victims, would suggest that Belfast’s experience of the revolution was actually quite different from that of the southern county.

A question of detail

When summing up Peter Hart’s work, one is left with a rather uncomfortable pebble in one’s shoe – this is the question of detail.

It is not my intention to enter into the debates on the minutiae of the sources used for Hart’s accounts of the Kilmichael ambush or Dunmanway killings. Rather, in a wider sense, Hart had a tendency to use numbers to back up his arguments, in some cases leaving puzzling questions for those researchers who followed him.

Hart’s use of numbers sometimes left puzzling questions for those researchers who followed him

For instance, in discussing what he called the “turn to soft targets” in 1921, he cites an incident in Cork city in February 1921, when the British executed six Volunteers by firing squad and in retaliation, the IRA shot 12 unarmed British soldiers (previously off duty troops had been left alone). The import of what Hart argued stands, in reprisal for British executions, the IRA extended their list of legitimate targets to unarmed troops, but he neglects to mention that only 6 of the shootings were fatal.[45]

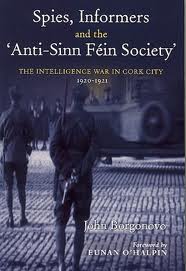

Similarly, in his discussion of the shootings of informers or soft targets in Cork city, Hart writes, “the city IRA carried out 8 successful attacks on patrols or barracks and fully 131 shootings of helpless victims”[46]. John Borgonovo, surveying the same time and place, found only 26 killings of informers in the city.[47] While clearly Hart’s shootings may not all have been fatal and “helpless victims” may include unarmed soldiers or policemen, the reader is left with a somewhat misleading impression.

A final example is a discussion of the Clonmult ambush, where 12 Volunteers were killed and after which the IRA shot a number of alleged informers, who they believed had led the British to their training camp.

Hart writes that, “in the aftermath, every suspected informer and every man in uniform became a legitimate target… Where none had previously been shot as a spy, six were killed in rapid succession”.[48] But a subsequent look at the ambush found only three such killings in the area in the four months after the ambush.[49] Again, the substance of what Hart writes is valid, but one can’t escape the feeling there is a certain exaggeration going on.

This is a real shame, in work that is based on such painstaking empirical and statistical work, as it calls into the question, mostly unnecessarily, the validity of his figures in general.

Summary

Peter Hart was a bold and provocative thinker whose work revolutionised the study of the Irish revolutionary period. Even his harshest critics would have to acknowledge that his research and writings have been the spur to a whole new generation of studies of the conflict – not all of whom necessarily agreed with his conclusions. He was also a talented writer, whose prose is always lively and readable.

Hart was a bold and provocative thinker. Even his harshest critics would have to acknowledge that his research have been the spur to a whole new generation of studies of the conflict

Anyone interested in the upheaval that led to Irish independence and partition and who is interested in questions like mass mobilisation, the spread and character of guerrilla warfare and the role of communal conflict will have to read and engage with Peter Hart’s work.

Unfortunately, much of the comment on Hart, before and after his tragically early death concentrated on relatively minor incidents, at the expense of his major arguments. In writing this review I am aware that I am merely skating on the surface of the vast detail and subtle argument presented in Hart’s work.

Readers may not agree with any of my views here, or indeed of Hart’s conclusions, but I strongly urge them to read his work for themselves before making up their minds and not to judge him based on third-party representations of his work in the media or on internet debate forums.

References

——————————————————————————–

[1] On Youth, Peter Hart, The IRA and its Enemies, p170-180, on class; IRA and its Enemies 140-147, on occupation, IRA and its Enemies, p155, Hart, The IRA at War, p114. On religion, IRA at War, p122-123

[2] The IRA and its Enemies p145

[3] IRA and its Enemies, p174-176

[4] Ernie O’Malley, On Another Man’s Wound p11

[5] Mossie Hartnett, Victory and Woe, Dublin 2002, p60

[6] Fergus Campbell, Land and Revolution, Nationalist Politics in the West of Ireland 1891-1921, p260

[7] IRA at War p21

[8] The IRA and its Enemies p207

[9] The IRA and its Enemies p 208

[10] IRA at War p96

[11] IRA at War p84

[12] IRA at War, p105

[13] IRA at War p 97

[14] The IRA and its Enemies p269

[15] The IRA and its Enemies p 87, Campbell, Land and revolution, p217

[16] IRA at War p 53

[17] IRA at War p58

[18] The IRA and its Enemies p106

[19] IRA at War, p32-42

[20] The IRA and its Enemies p 51

[21] The IRA and its Enemies, pp. 87, 116, 120-123

[22] The IRA its Enemies p122

[23] The IRA and its Enemies p89

[24] The IRA and its Enemies p87

[25] Padraig Og O Ruairc, Blood on the Banner, The Republican Struggle in Clare, pp 325, 330-331

[26] Marie Coleman, County Longford and the Irish Revolution, p132-133, 153-155

[27] Fearghal McGarry, Eoin O’Duffy, a Self Made Hero, p54, 70-71

[28] Tom Doyle, The Civil War in Kerry, p323-333. Out of 180 deaths in the Civil War in Kerry, only 12 were civilians and most of them were accidentally shot in the crossfire.

[29] IRA at War, p240

[30] IRA at War p20

[31] IRA and its Enemies, p288,

[32] IRA and its Enemies, p314

[33] IRA and it Enemies, p290

[34] T Ryle Dwyer, Tans Terror and Troubles, Kerry’s Real Fighting Story 1912-1923, pp289, 299, 305-307

[35] The IRA and its Enemies p282 According to Meda Ryan, Tom Barry, IRA Freedom Fighter, those shot were found on a list of ‘helpful citizens’ kept by the Auxiliaries in Dunmanway. P213

[36] Tom Barry, Guerrilla Days in Ireland, p214

[37] Mossie Hartnett, Victory and Woe, p131

[38] IRA at War, p22

[39] The IRA and its Enemies p125

[40] IRA at War p245

[41] Ibid

[42] IRA at War p252

[43] Peter Hart in, Joost Augusteijn (ed), The Irish Revolution, p25

[44] IRA at War p249-50

[45] The IRA and its Enemies, p99, John Borgonovo, Spies, Informers and the Sinn Fein Society, The Intelligence War in Cork City 1920-1921p25

[46] IRA and its Enemies, p99

[47] Borgonovo, Spies, Informers and the Sinn Fein Society, , p83

[48] The IRA and its Enemies, p98

[49] Tom O’Neill, The Battle of Clonmult, The IRA’s Worst Defeat, p65-68

Bibliography

*Augusteijn, Joost (ed), The Irish Revolution, 1913-1923, Palgrave Macmillan, Hampshire, 2002.

*Barry, Tom, Guerrilla Days in Ireland, Anvil Books, Dublin 1997.

*Borgonovo, John, , Spies, Informers and the Sinn Fein Society, The Intelligence War in Cork City 1920-1921, Irish Academic Press, Dublin 2007.

*Campbell, Fergus, Land and Revolution, Nationalist Politics in the West of Ireland 1891-1921, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2008.

*Coleman, Marie, County Longford and the Irish Revolution 19190-1923, Irish Academic Press, Dublin 2006.

*Doyle, Tom, The Civil War in Kerry, Mercier, Cork, 2008.

*Dwyer, Ryle T., Tans, Terror and Troubles, Kerry’s Real Fighting Story, Mercier Press, Cork, 2001.

*Hart, Peter, Mick, The Real Michael Collins, Macmillan, London 2006.

*Hart, Peter, The IRA at War, 1916-1923, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2005

*Mossie Hartnett, Edited by James H Joy, Victory and Woe, UCD Press, Dublin 2002.

*McGarry, Fearghal, Eoin ODuffy, A self Made Hero, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2007.

*O’Neill, Tom, The Battle of Clonmult, the IRA’s Worst Defeat, Nonsuch, Dublin 2002.

*O’Malley, Ernie, On Another Man’s Wound, Anvil Books, Dublin 2002.

*Ryan, Meda, Tom Barry, IRA Freedom Fighter, Mercier Press, Cork 2003.