‘Rough and Ready Work’ – The Special Infantry Corps

John Dorney looks at a unit of the National Army raised during the Civil War of 1922-23 to put down agrarian agitation and strikes.

On September 8th, 1923, the Civic Guard or Free State police, at Milltown Malbay, County Clare, requested an armed military ‘covering party’ to ‘protect them while effecting an arrest’ at Seafield, a rural townland near Quilty.

Small wonder that the unarmed Civic Guard wanted a military escort. The country was still awash with illegally-held weapons after the Civil War. Arresting organised bodies of men – be they politically motivated or not – was dangerous work.

The Special Infantry Corps was a unit of the Free State’s National Army, founded in January 1923 during the Irish Civil War and wound up in December of that year.

Captain Scannell of the National Army detailed a party of soldiers to help the Guards and eight men were duly arrested for ‘forcible grazing of lands’. The eight were held in Milltown Malbay, and guarded by the military, ‘whilst waiting for the formation of a civil court to deal with them.’ They were finally released on bail.

In the military report, the section for ‘reason for arrest’, stated ‘nil’. In other words there was no formal charge. The men had been arrested under the Emergency Legislation which had been enacted during the Civil War. This was the reality of Ireland in mid 1923. There was still no functioning police or courts system in much of the country and the state’s authority, even in civil matters was generally enforced by the military.

The soldiers responsible for the arrests at Seafield belonged to a unit specifically raised to put down social disorder. It was named the Special Infantry Corps.[1]

Background, ‘anarchy and a new Land War’

The Special Infantry Corps was a unit of the Free State’s National Army, founded in January 1923 during the Irish Civil War and wound up in December of that year.

Its purpose was not to combat the anti-Treaty IRA guerrillas but to put down a wave of illegal land occupations, cattle driving and strikes that flourished during the Civil War.

Much of Ireland had been essentially un-policed since early 1920 when the IRA campaign against Crown Forces had begun in earnest and especially since the Anglo-Irish Treaty of 1922. This had disbanded the Royal Irish Constabulary and withdrawn the British Army, first to barracks and then out of the country altogether, in most cases by April 1922, with the last contingent leaving Dublin in December.

The IRA and the Irish Republican Police (IRP) were supposed to step into the vacuum and to enforce order, but they were ill-suited to the task and in any case, soon split into antagonistic factions over the Treaty. Civil War broke out between and pro and anti-Treaty sides in late June 1922.

This all happened at a time of heightened class and agrarian conflict in rural Ireland, when a slump in agricultural prices created severe hardship. In County Leitrim for instance, in April 1922, the poor were reported to be going hungry in the ‘Worst year for farmers since ’47’ [1847 the worst year of the Great Famine]. Some 100,000 tenants were seeking to buy out or otherwise seize their landlords’ holdings and many of them had been on rent strike since late 1921.

The Irish Civil War saw state breakdown in many parts of Ireland, exacerbated by land hunger and class conflict.

Meanwhile as exporting farmers, hit by the recession, sought to bring down wages of their labourers they sparked off a flurry of strikes that peaked in spring 1922 and the summer of 1923.[2]

During the Civil War, state power broke down altogether in much of Ireland. The new Irish police force, the Civic Guard, was unable to face down armed anti-Treaty guerrillas and in many areas National Army authority did not extend beyond well-fortified towns in the countryside. In any case the Army was most reluctant to get involved in policing work.

On the other side, the anti-Treaty IRA positively encouraged agrarian and social agitation in some area as it undermined the Free State’s authority. For instance National Army Intelligence, reported a case in November 1922 in which ’17 armed Irregulars’ visited a farmer named Byrne in County Cavan and forced him to sign over his land to one of their supporters, the Army concluded, ‘The Irregulars are taking advantage of the present state of the country to annex a farm for one of their supporters’.[3]

The roots of the Special Infantry Corps lay in the increasing disquiet of two members of the Free State cabinet in early 1923 about the law and order situation in rural areas; Kevin O’Higgins, Minister for Home Affairs and Patrick Hogan, Minister for Agriculture.

Hogan warned of ‘anarchy’ and a new Land War’ in late 1922 by people, ‘with a vested interest in chaos’. He argued that the Army needed to take on such tasks as land clearing, debt collection, strike breaking and evictions, and recommended troops be used, ‘who are unknown in the locality’.[4]

Kevin O’Higgins, a Minister known for his hawkish views, believed that the bedrock of the anti-Treaty IRA’s support was not Republican idealism but ‘greed, envy, lust, drunkenness and irresponsibility under a political banner’. The ‘Irregular’ campaign, depended on the support of ‘people in possession of land and property not legally theirs, people who owe money or are engaged in illegal activities such as poitín [illegal liquor] making’.

Minister Kevin O’Higgins argued that a new section of the Army was needed to put down social disorder, or ‘passive irregulars’.

O’Higgins warned that the existing legal system had broken down, especially in counties Galway, Roscommon, Cork, Kerry and Limerick. ‘It is not a war properly so –called’, he told his cabinet colleagues but, ‘organised sabotage and disintegration of the social fabric.’ ‘The Army must act as armed police as well as military’ in order to ‘vindicate the idea of law and ordered government’.

He cited cases where the National Army was in occupation of a town but three miles outside it, farms were being seized, farmers were on rent strike against paying annuities (owed to the British government for land purchase) and cattle were being illegally ‘driven’.

There was a need, he argued, for a new Army corps to clear occupied land, enforce the rulings of the courts by collecting rents, annuities and taxes and to ‘stamp out poitín traffic’.

He concluded that to bring the Civil War to an end, the government needed increased ‘sternness’ both with the ‘active Irregulars’ (anti-Treaty IRA guerrillas, for whom he advocated execution) and the ‘passive irregulars’ who did not pay their rates, taxes and rents’.[5]

O’Higgins is sometimes accused of exaggerating the extent of the law and order problem but a closer look at one of the affected regions, the Cavan/Monaghan area along the new border, shows precisely how serious the problem was. Violence was routinely being used to settle local agrarian conflicts.

On September 30th, for instance in Cavan, armed men of undetermined allegiance raided the O’Brien family house, ‘put them out’, threw away their milk and killed their hens, it was thought as a result of a land dispute.[6] Some days later, another armed band abducted farmer Peter Lennon at Ballybay, Monaghan and ordered him to forego a land claim in Lurgan (County Cavan). Shots were also fired into another farmer named Mitchel’s house.[7] In November there was a raid on the property of ‘extensive landowner’ John Bolton, High Sherriff for Monaghan, who fired shots at the attackers.[8]

These were by no means isolated incidents, even in this small region. Rather they represented an intensification of disorder that had been afoot since early 1922.

The local newspaper, the Anglo Celt noted that people were trying to reclaim land ‘where their fathers were evicted’. An evicted tenants meeting Cavan Town Hall heard from Mr MacAbhareagh (McAvery) the Chairman, ‘We need to recover the land from which our fathers and grandfathers were thrown off without law or justice’.[9]

Interestingly, while the likes of O’Higgins saw only greed and avarice in agrarian activism, many landless men and small farmers saw themselves as righting historic injustices caused by decades of conflict and evictions on the land since the 19th century.

Before the outbreak of Civil War, the IRA had been able to mediate such disputes to a degree. For instance in June 1922 in Ballyhaise, Cavan, when 200 Labourers seized a bog from a local landowner and marked out individual plots for cutting, the local IRA intervened and started arbitration with the landowner.[10]

Now with pro and anti-Treaty factions busy fighting each other, there was no authority at all in many rural areas.

The composition of the Special Infantry Corps.

The Special Infantry Corps (SIC) was composed of about 4,000 men and commanded by Patrick Dalton, a veteran of the Easter Rising and the pre-Truce IRA.[11] Essentially its role was that of an armed gendarmerie rather than a military unit, in that its primary responsibility was not hunting down or fighting ‘Irregulars’ (as the Free State termed the anti-Treaty IRA), but enforcing the law and arresting land grabbers, strikers and other social protesters. In fact the SIC was expressly ordered not to arrest ‘Irregulars’ but to leave that job to the regular Army.[12]

The soldiers in the SIC were paid less than the regular Army and their officers were frequently men who had been moved out of jobs in Intelligence and other sensitive posts for their poor performance or indiscipline in a National Army reorganisation of January 1923. Frequently those so moved were IRA veterans who were deemed to have performed poorly as regular soldiers.

The Special Infantry Corps was largely officered by IRA veterans seconded from other parts of the Army after its reorganisation in early 1923.

One such was James Patrick Conroy, by origin a house painter from Seville Place in Dublin’s north inner city. He was a veteran of ‘the Squad’ and had been ‘out’ on Bloody Sunday in 1920 and the Customs House raid of 1921 at which he had been captured. In the Civil War in the Dublin Guard, he had seen action in Cork and Kerry before being made commander of the Special Infantry Corps 5th Battalion.[13]

Like James Conroy, Daniel Finlayson (who was also a house painter from Dublin) was involved in killing British Intelligence officers in November 1920 and like Conroy was arrested and imprisoned after the Customs House raid. In the Civil War he briefly served in the Free State’s Intelligence Unit, the CID. Then, like Conroy was sent to Kerry with the Dublin Guard. He was also made a captain in the SIC in early 1923.[14]

From a similar Dublin pre-Truce IRA background was Michael Lawless, another shooter on Bloody Sunday in 1920, who in the Civil War served in Limerick and Galway before being seconded as a captain to the 1st battalion Special Infantry Corps.[15]

The SIC in action

The SIC was deployed to various ‘disturbed’ areas in February 1923. According to Kevin O’Higgins, it performed its task well. ‘Established via a memorandum of the Minister of Agriculture and myself, it did rough and ready work in stamping out agrarian anarchy and other serious abuses’.[16]

Most of the Special Infantry Corps work involved arrests for agrarian offences, and collecting unpaid rents, rates and taxes. This made it very unpopular in rural areas.

Others, even inside the National Army, were less complimentary however. National Army Dublin Command (which covered most of the north and east of the country), Intelligence reported that the Special Infantry Corps were deployed into Cavan and Monaghan in July 1923 where there was persistent social unrest.

The Army reported threatening letters sent to land owners, a strike by road workers, who voiced hostility to the Army and meetings of unpurchased tenants, where, likewise anti-government view were expressed.

By the summer of 1923, National Army Intelligence was reporting that the Special Infantry Corps was ‘having a very bad effect on the civil population in most districts where it is stationed’. The Corps’ personnel it complained, were men of ‘low morals’.[17]

What precisely this means, we can only surmise. It may simply mean that the SIC troops were lazy and uncouth. Or it may refer to abuse of civilians, drunkenness and possibly beatings and extortion of the local populace, as well as the unpopular work of collecting rents, rates and taxes and evicting illegal land occupiers.

A pro-Treaty TD for Cork lamented that the SIC was seizing land from the same poor hill farmers who had always supported the IRA against the British; ‘these people gave us assistance when we were out in the hills fighting against an alien government. I think it is a very bad action for the government to seize cattle on these farms for arrears of rent due to English landlords’.[18]

The SIC’s reporting of its arrests was patchy until July 1923, thereafter it reported operations such as the following; In Carna, Connemara, five men were arrested for being ‘in illegal possession of lands belonging to Mr Morgan’. At Fernhill County Mayo four men were detained for ‘driving [i.e. stealing] the cattle of Mr Kelly’.

In County Clare, there were twelve arrests at Mountshannon for ‘conspiracy – the forcible grazing of lands’. From August 17th to 20th 1923 there were 32 arrests in Carrickonshannon County Leitrim for ‘cattle-maiming, unlawful grazing, shooting cattle and unlawful working of a bog’. Most of these prisoners were however released after signing, ‘a declaration to keep the peace’.[19]

In some cases though the charges were more serious and those arrested were interned indefinitely. The SIC Battalion in Galway reported 42 arrests in May 1923 of whom four were to be tried for the attempted murder of Mr Naughton in a land dispute in Carna, County Mayo.[20]

Cattle that had been grazing on occupied land were seized by the troops and sold off in Dublin. In Roscommon the Free State troops fired over the heads of a crowd trying to prevent the impounding of animals.[21]

Patrick Hogan the Minister for Agriculture also appealed for the Criminal Investigation Department or CID, the Free State’s much feared plain clothed detective unit, to be sent to assist the Special Infantry Corps to combat, ‘agrarian outrages’. [22]

A meeting of unpurchased tenants in Ballybay, Monaghan – 100 delegates, representing farmers on rent strike since early 1922 – heard that the CID had been used to collect landlords’ rent. One Father Maguire declared, that while there should not be ‘armed resistance’, it was ‘terrible for the government to lift money for absentee landlords who never spend a penny in the country’. [23]

The anti-Treaty IRA leadership for their part saw some potential in agrarian strife, not so much as an end in itself, but to build up support for an anti-state position and whenever possible they took steps to support agrarian agitators. For instance in March 1923, Liam Lynch, IRA Chief of Staff endorsed a proposal by Sean Russell IRA Quartermaster, to ‘take action’ against a cattle agent named Cuddy who was selling cattle seized by Free State forces in Roscommon and selling it to England at Dublin’s North Wall.[24]

The administration of the Special Infantry Corps was always sloppy. In August and again in September 1923 (by which time the Corps had been deployed for about eight months), Michael Costello, head of National Army Intelligence, appealed for lists of prisoners taken by the SIC to be provided so that they could be brought before civil courts.

The Corps’ records show 317 arrests but this probably underestimates its activity.

He later appealed again for SIC units to provide details of who they had arrested in the period since their last report and reminded them that even if they made no arrests they still had to file reports. There followed a lengthy series of reports from many areas that listed no arrests made in the intervening period. [25]

In total the SIC recorded 371 arrests from January to September 1923, of whom 219 had been released and 152 were still in custody. Of these the majority, 173 were for agrarian offences, with 128 accused of ‘miscellaneous’ crimes and only 8 ‘political prisoners’. They had also issued fines amounting to £5,591 (£1,764 in County Tipperary alone) and had seized 1,553 cattle and 5 motor cars.[26]

However it would probably a mistake to take this as the sum total of SIC activity. For one thing, arrests continued for another three months, up to December 1923. More importantly though, we must ask what the surviving documents do not tell us.

Kevin O’Higgins referred to ‘rough and ready work’ of the SIC. How many cases did Special Infantry Corps men settle with beatings and intimidation that saved them having to fill out the bothersome paperwork associated with formal arrests? The archival sources do not tell us such things but it seems likely that they occurred.

Strikes

The Special Infantry Corps was generally extremely unpopular among small and medium sized farmers in rural areas, many of which remained ‘disturbed’ well into late 1923.

Where the farmers generally approved of state intervention, however, was where it put down strikes and factory occupations. Strikes by agricultural labourers had become endemic in 1922 as workers fought against wage cuts imposed by employers – especially farmers – hard hit by the slump in agricultural prices.

The Free State was concerned from its earliest days about left-wing subversion as well as ‘Irregular’ IRA military action.

In Monaghan the Farmers’ Union warned of class war as early as January 1922; ‘The farmer goes to work with a revolver in one hand for the time to come’ they stated. Father Murphy (the chair) urged Irish government to ‘fight [farmers’] battles for them’. He warned that ‘Farmers may have to fight labour’. Not reputable unions, he warned, but ‘Disorderly labour, hooligans’. The ‘Government should put down a firm hand’. In south he warned, ‘houses have been burnt, farm produce burnt’. [27]

The Free State was concerned from its earliest days about left-wing subversion as well as ‘Irregular’ IRA military action. In July 1922, Michael Collins, then Commander in Chief of the National Army detailed his then Director of Intelligence Liam Tobin to tap the phones of ‘well known anti[Treatyites]s, Bolsheviks, Fianna, Cumann na mBan and the IWW [International Workers of the World].’[28]

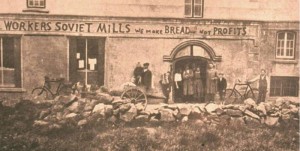

In in May-June 1922, striking workers at Cleeves milk factories in County Limerick had raised a red flag over the plants and declared a ‘Soviet’ and workers in the Tipperary town gasworks did likewise. These occupations were eventually ended after the Civil War started and Free State troops wrested these areas off the Republican guerrillas (who had grudgingly tolerated the ‘Soviets’) and returned the plants to their owners. [29]

Such ‘Soviets’ represented a radical tactic to resist wage cuts, more than a desire for socialist revolution, but they still scared farmers and other employers. At a meeting of the farmers Union in Dublin May 1922, delegates voiced the opinion that the Knocklong occupation represented, ‘the thin end of the wedge of Bolshevism’. ‘We cannot tolerate that workers step in and take over works to which they have no legal right whatsoever’.[30]

The truth was that radical socialism was a fringe movement in Ireland, but strikes, in the atmosphere of the collapse of state power in 1922-23, were nevertheless widespread and often descended into violence.

In August 1922 for instance, violence flared in a series of dispute between agricultural workers and farmers in the border region. On August 5th at Anny County Monaghan, a Farmers Union member James McGinnity was shot dead in a labour dispute. The ITGWU union condemned killing but their own language was often radical.

With no effective policing, strikes often descended into violence in 1922-23.

In a meeting of the ITGWU on August 19th at Arva Mr Redmond ITGWU said , ‘we are constantly scrapping with the capitalists and seldom come off second best.’ ‘We want the factories and the land’. On September 9th a farmer was stabbed by a worker with a pitchfork in a dispute at Shercock, County Cavan.[31]

National Army troops had already been used to forcibly break up pickets in a strike of the Postal Service in September 1922. In early 1923 at the time when the Special Infantry Corps was founded, Kevin O’Higgins was particularly concerned about a strike of agricultural labourers in Kildare in which shots had been fired by both sides. O’Higgins wanted ITGWU organiser C.J Supple arrested for burning farmers’ property at Athy.[32]

In February 1923, the National Army officers were given directions that in the case of strikers occupying buildings, ‘orders should be given at once to evacuate buildings and in the event of non-compliance, all necessary force should be used’.[33]

The Special Infantry Corps’ most large scale and violent deployment came in a strike in Kilmacthomas, County Waterford that lasted from May to November 1923, in which 1,500 agricultural workers were locked out for refusing to take a pay cut and longer working hours.

By the summer of 1923, 600 troops under General Prout were stationed in the County, which was put under martial law, and a curfew was put in place. A Labour TD, John Butler was arrested and farmers formed their own self-styled ‘White Guards’, who beat up union activists and burned their cottages. [34]

The SIC’s largest and most violent deployment was in putting down a strike in County Waterford in mid 1923.

The strike occurred after the IRA ceasefire and ‘dump arms order’ that ended the Civil War proper but both armed factions seem to have used weapons during its course. National Army Intelligence recorded that masked members of either the Special Infantry Corps or the CID had burned seven labourers’ cottages in reprisal for attacks on farmers’ property; ‘such actions are regrettable but are the only way to stop burnings by the labour crowd’ the Intelligence officer concluded. [35]

Anti-Treaty Republican and later communist activist Frank Edwards recalled, ‘It was a localised civil war but a more logical one [than the war over the Treaty]… the Free State Army had to convey the farm crops and stock to the towns’. The workers, whether IRA members or simply union men with access to guns, sniped at the convoys, who returned fire.[36] In some cases, the firefights were quite prolonged, lasting up to 20 minutes.

County Waterford was declared a military area and put under curfew during the strike. The SIC records show that 62 men were arrested in this area during the strike. Their records are not extensive but give us some idea of routine SIC activity there. For example on August 18th 1923, six men were arrested ‘for threatening to assault a labourer’, presumably one who had not joined the strike, and on October 19th five men were arrested in Dungarvan for assault, breaking windows and breaking the curfew.[37]

The strike was finally broken when hunger and shortage of funds forced the workers to accept pay cuts in November 1923.

Disbandment

The SIC was disbanded in late 1923, as part of process of demobilising the hugely bloated National Army after the Civil War to stave off state bankruptcy. The Special Infantry along with other auxiliary Army units such as the Railway Protection Corps were among the first units to be demobilised.

The Special Infantry Corps was disbanded in late 1923. Some of its officers were involved in the Army Mutiny of the following year.

The Corps does not seem to have suffered many casualties during its deployment but at least one officer, Captain Michael Keogh was killed in a bomb explosion in June 1923 in Mallow County Cork and another Lieutenant Arthur of Belfast was shot in the neck in County Waterford in October 1923 during the strike there.[38]

Most of its men were simply discharged with a redundancy payment, while many of its officers ‘hung around Dublin’ without specified duties for the following months. Some of them got involved in the attempted Army mutiny of March 1924, in which disgruntled former IRA National Army officers protested against their demobilisation. Michael Lawless, one of the ex Dublin IRA SIC Officers recalled, ‘I was to take part in the army mutiny, my job being to seize the “Brian Houlihan” barracks outside Tralee where I was then stationed.’

James Conroy, commander of the SIC’s Fifth Battalion, fled to America after coming under suspicion for the murder of a Jewish civilian, Emmanuel Kahn, in Dublin in November 1923.[39]

By that time most of the country was again peaceful enough for the newly established, unarmed Civic Guard (or Garda Siochana as they began to called from 1924) to be able to take over policing duties from the Army. The wave of social and agrarian disturbance that had flared up during the revolutionary years of 1918-23 had blown itself out.

On the land agrarian discontent was headed off by a Free State land Act of 1923, which helped to take the sting out of much agrarian activism.

Interpreting the Special Infantry Corps

To the likes of Kevin O’Higgins, the Irish Civil War was not only a military campaign to put down the ‘Irregulars’ but also a struggle to uphold ‘law and order’ amid state collapse and social ‘anarchy’. In this regard, he thought that his creation the Special Infantry Corps had done a splendid job.

To the pro-Treaty side the Special Infantry Corps was an indispensable part of restoring social order in 1923. To others it represented ‘counter-revolution’.

To be fair to the SIC, many of the activities they countered – illegal poitín distilling, land-grabbing cattle driving and the like – were simply manifestations of personal acquisitiveness. Where the anti-Treaty IRA controlled the countryside, they also tried to put a stop to such things.

To others though, the SIC was just a manifestation of the Free State’s repressive reconstitution of Irish society around the pillars of the farming class, the Catholic Church and state institutions.

Republicans campaigning in the election of August 1923 argued that ‘The Land Bill is only election bait, of course it made landlords safe and tenants had to pay. Who are the landlords? [Voices ‘Cromwell’s descendants’]. The land was taken from the Irish people’s grandfathers, and was it got honestly? The farmer’s son has it hard to get rent together’… ‘No wonder there is emigration’. While a Labour candidate argued that, ‘Ranches should be broken up and divided among the people’. [40]

And it was in precisely these poor, marginal rural areas that Fianna Fail, the party that emerged from the anti-Treaty side, built much its support base in the later 1920s –eventually overthrowing the pro-Treaty side in the arena of electoral politics.

To conclude, the Special Infantry Corps to some degree represents simply the Free State’s enforcing of its monopoly on force within its territory. In another sense though its imposition of order was partial enough in favour of the existing possessing classes for some to see it rather as part of an Irish counter-revolution.

References

[1] Military Archives, Cathal Brugha Barracks, Summary of Special Infantry Corps Arrests, cw/P/02/02/02

[2] Reported in Anglo Celt April 22 and May 6, 1922

[3] National Army Reports, Eastern Command, cw/ops/07/01

[4] Cited in Gavin Foster, The Irish Civil War and Society, p131

[5] Memo dated 11 January 1923, submitted to Army Inquiry 1924, UCD Mulcahy Papers P/7/C/21

[6] Anglo Celt September 31, 1922

[7] Anglo Celt October 1th 1922

[8] Ibid. November 11 1922

[9] Ibid. November 23 1922

[10] Ibid. June 17, 1922

[11] Gavin Foster, The Irish Civil War and Society, p132

[12] Order Issued by NA Director of Intelligence Michael Costello, 7 August 1923 Military Archives Summary of Special Infantry Corps Arrests, cw/P/02/02/02

[13] Military Pensions file 24SP80 http://mspcsearch.militaryarchives.ie/detail.aspx?parentpriref=

[14] Military Pensions file 24SP2125 http://mspcsearch.militaryarchives.ie/detail.aspx?parentpriref=

[15] Michael Joe Lawless WS 727 Bureau of Military History

[16] O’Higgins testimony to Army Inquiry, March 1924, UCD Mulcahy Papers P/7/C/21 UCD

[17] National Army Dublin Command Intelligence Report Numbers 12 – 16 cw/ops/07/16

[18] Terence Dooley, the Land for the People, p51

[19] Military Archives Summary of Special Infantry Corps Arrests, cw/P/02/02/02

[20] Ibid.

[21] Terence Dooley, the Land for the People, p51

[22] Cabinet minutes 23 April 1923 Mulcahy Papers UCD P/7/B/247

[23] Anglo Celt March 17 1923

[24] UCD Twomey Papers Sean Russell to IRA D/I14/3/23 and Liam Lynch CS to D/I 16/3/23 P/69/11

[25] Summary of Special Infantry Corps Arrests, cw/P/02/02/02

[26] Ibid.

[27] Anglo Celt, January 28, 1922

[28] Collins to Tobin, 19/7/22 UCD Mulcahy Papers p/7/B/4

[29] Conor Kostick, Revolution in Ireland, Popular Militancy 1917-23, p203-204

[30] Irish Times, May 19, 1922

[31] Anglo Celt August 5, August 19 and September 9, 1922.

[32] Cabinet Minutes, 17 January 1923, Mulcahy Papers UCD P/7/B/247

[33] Cabinet Minutes, 27 February 1923, Mulcahy Papers UCD P/7/B/247

[34] Kostick Revolution in Ireland, p205-207 See also Emmet O’Connor, Agrarian Unrest and the Labour Movement in Waterford, 1917-1923, in Saothar, Labour History Journal, 1980, Vol. 6 p48-53

[35] National Army Dublin District Reports, UCd Mulcahy Papers MP/7/B/139

[36] Uinseann MacEoin, Survivors, Argenta 1980, p5

[37] Military Archives Summary of Special Infantry Corps Arrests, cw/P/02/02/02

[38] Irish Times, June 22, 1923 and October 17 1923

[39] Michael Lawless BMH, James Conroy Military Pension Claim, http://mspcsearch.militaryarchives.ie/detail.aspx?parentpriref

[40] The Speaker was Republican activist Cathal O’Byrne, speaking in Cavan, reported in the Anglo Celt August 11, 1922.