Book Review: Architects of the Resurrection: Ailtirí na hAiséirghe and the fascist ‘new order’ in Ireland

By R.M. Douglas

By R.M. Douglas

Published by Manchester Univrsity Press, 2009.

Reviewer: Daniel Murray

Fascists these days are a mealy-mouthed lot. Not racist but racialist. Not hating another race but loving your own. So it is almost refreshing to encounter some who were upfront about what they were about. Formed in 1942 while their fellow fascists on the Continent were in the ascendant, Ailtirí na hAiséirghe (“Architects of the Resurrection”) had a set of policies that were as grandiose as its name:

- Irish democracy to be replaced by a one-party totalitarian state (said party being itself, of course).

- The use of English to be criminalised in favour of Irish.

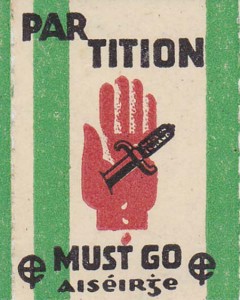

- A united Ireland to be achieved by the raising of a massive conscript army that would swamp Northern Ireland into submission.

- The encouragement of women to swell the Irish race with as many progeny as they could manage, the earlier the better (how else is that massive conscript army going to be formed?).

Ailtirí na hAiséirghe (“Architects of the Resurrection”) were an avowedly fascist group operatingin the 1940s.

Too bad if none of this strikes the reader as appealing, as emigration would also be banned. One has to give Ailtirí credit at least for not resorting to the usual Irish solution to social problems.

Despite its avowedly fascist worldview, Ailtirí did not see itself as simply a potato-eating version of those found in Germany and Italy. Instead, it held a far grander ambition: by remaining aloof from the War until the belligerents had worn themselves out, Ireland would be in the prime position to re-spiritualise a materialistic Europe and assume the mantle of leadership over a Christian world order.

The study of a political party can read like a biography: it will have its beginning and often an end, a distinct character that stands it out from the rest, likes and dislikes, and sometimes a rise and a fall.

The study of a political party can read like a biography: it will have its beginning and often an end, a distinct character that stands it out from the rest, likes and dislikes, and sometimes a rise and a fall.

Ailtirí had a promising start before spluttering into oblivion but then, political failures can be as interesting as the successes, especially if the reader is of a morbid disposition. Parties on the far-right spectrum, in particular, can have the appeal of a car-wreck: grisly but you slow down to gawp all the same.

Perhaps it is the type of personality they attract. Not that left-wing groups do not feature their own sort of deviant – Ken Livingstone’s 2012 memoir records the Machiavellian manoeuvrings of the various Trotskyite factions he was part of with a little too much relish – but the fascistic ones do seem to draw more than their fair share of ambitions and egos inflated to levels that are almost Shakespearean. That is, if Shakespeare was a fruitcake.

The opening chapter explores the uneasy position democracy had within post-Treaty Ireland with its legacy of civil war and executions, Blueshirts battling against Republicans, and the widespread idea that an autocratic system like those used so successfully on the Continent might be preferable to godless Marxism. The reviewer is not completely convinced by the direction of this chapter – seen in another light, Irish democracy could appear to have been impressively robust – but it is, as with the rest of the book, an impressively researched piece.

Douglas next explores the pro-German sympathies prominent in Ireland on the eve of the Second World War that only grew with the strings of victories by the Nazi state that seemed about to consign democracy to the dustbin of history. The author then narrows his focus onto the political evolution of the party founder, Gearóid Ó Cuinneagáin, the closest the book has to a recurring character besides the party itself.

The party envisaged re-conquering Northern Ireland and banning the English langauge.

Born Gerald Cunningham in Belfast, 1910, he worked as a tax clerk in the Irish Department of Finance before resigning when refused leave to improve his Irish. Having immersed himself in a Gaeltacht and emerging as a committed Gaelic revivalist, the newly renamed Ó Cuinneagáin worked first as an editorial writer and then as a tax consultant before taking his first step into political thought.

After flirting with first an underground pro-German group and then with the Gaelic League – where he excelled as an organiser before his outspoken politics proved a mite strong for the League’s genteel elders – Ó Cuinneagáin felt confident enough to form his own party, one that he could have to himself and play the role of leader, or Ceannaire as the budding fuhrer was styled. All that was left was to make a lot of speeches, and then sit back and wait for the inevitable bestowment of supreme power.

Ailtirí was not to be another mere party but a vanguard for a Christian revival. Still, it had to abide by the nuts-and-bolts realities that every political group must go through, such as the management of its regional branches (many of whom would withhold knowledge of their full strength to avoid the extortionate 75% tithe on their membership fees by the Dublin HQ), the maintenance of self-imposed standards (the rule against holding party meetings in public houses being commonly ignored as the local pub in some rural areas was often the only place large enough), and time commitments on the part of activists (senior ones often travelling considerable distances to speak at branch events).

While Douglas’ book hardly invites admiration for its subject, it is still incredible that Ailtirí worked at all, let alone as well as it did. Enthusiasm among members for the party ideals remained high enough not to be deterred by their inept performance in the 1943 general election. It was the repeated failure in the 1944 one, however, that led party activists to wonder if they would be better off under a different ceannaire.

Ó Cuinneagáin was, as Douglas describes, the party’s best asset and worst liability. While an effective organiser, his inability to delegate responsibility – and power – meant that the future of Ailtirí was always going to be held hostage to the Ceannaire’s increasingly obvious flaws.

Ó Cuinneagáin appears to have been of that breed of ambitious politicians who either enter a small political scene or, upon failing to find one, create their own. Their competency level is at a reasonable but unexceptional level, allowing them the success that would otherwise have eluded them in a more mainstream party but leaving them vulnerable to themselves when it comes to competing on a national stage. Nick Griffin’s meltdown on BBC’s Question Time in 2009 is the most notable example of this political Peter Principle at work.

While Ó Cuinneagáin avoided anything quite so public, his inflexible and dogmatic approach to leadership led to the 1945 resignations of some of Ailtirí’s ablest members and what Brendan Behan described as the first item on the agenda of any Irish committee: the split. In disarray and with the recently formed Clann na Poblachta encroaching on its share of the protest vote, Ailtirí made the lightest of impacts on the 1948 general election.

After poor performances in the 1943 and 1944 elections the party faded way

Even then, Ó Cuinneagáin did not give up: on the morning of 14th May 1949, the inhabitants of Dublin and other large towns awoke to find Ailtirí posters exhorting them to “Arm Now to Take the North.” The heavy-handed response by the Gardaí in tearing down the posters provided Ailtirí with a propaganda boon, and the whole affair seems to have partly convinced the British Cabinet of an imminent invasion of Northern Ireland.

But the lack of follow-up by Ailtirí proved to many that the party was all talk and no action. Even an attempt later in the year to upstage the annual Armistice Day dance in Dublin with a riot failed to stem the haemorrhaging of members.

Douglas is an entertaining writer who knows how to bring his subject to life makes for an absorbing as well as informative read.

One of the stalwarts remaining was Liam Creagh who, when not a drinking companion to Brendan Behan, helped sell the Ailtirí newspaper and occasionally drink the proceeds away. The relationship between Creagh and Ó Cuinneagáin came to resemble, as Douglas describes with his keen eye for human folly, a “dysfunctional marriage”, though Creagh was not the most damaged individual in Ailtirí, that dubious distinction being held by Raymond Moulton Sean O’Brien, a self-proclaimed ‘Prince of Thormond’ and compulsive child molester. The best that can be said for many far-right groups is that all human life is there.

Ailtirí shrank away until its newsletter was the only part of it left, a party broadsheet without a party. The newspaper enjoyed surprisingly healthy sales throughout the 1950s and 1960s – Ó Cuinneagáin appears to have been far more skilled as a publisher than as a politician or thinker – but by the next decade, its publishing costs proved too much even for the indefatigable Ó Cuinneagáin, and it was wrapped up in 1975. The one-time Ceannaire died in 1990, still insisting that Ailtirí’s day might yet come.

While destined to go down in history as a footnote, and a peculiar one at that, Douglas is at pains to stress how Ailtirí’s ideology was not all that incompatible with popular opinion in Ireland at the time, with its pro-Axis sympathies even after the full extent of Nazi atrocities had been exposed, and the latent anti-Semitism in public life (it is unsurprising to learn that the Jew-baiting blowhard Oliver J. Flanagan was happy to field questions on behalf of Ailtirí in the Daíl).

However, unlike Martin Pugh’s study on fascism in Britain at the same time, Hurrah for the Blackshirts! (2005), in which half the chapters seemed to be dedicated to peripheral subjects, Douglas is able to provide the necessary cultural context while keeping the attention on the main subject. That Douglas is an entertaining writer who knows how to bring his subject to life makes for an absorbing as well as informative read.