The ‘Bridges Job’ – Dublin, August 5-6 1922

John Dorney on a disastrous operation by the IRA in Dublin during the Irish Civil War.

On the early morning of August 5th 1922, some 200 or more young men were mobilised around Dublin city. Some were armed with handguns and grenades, some had explosives and detonating equipment , others carried merely spades and picks.

Working in groups of between 5 and 40, they began digging trenches in roads leading into the city, dismantling stone bridges that forded Dublin’s rivers and canals, and laying explosives in road and railways bridges, while the armed men scanned the horizon for signs of hostile soldiers. Parties were sighted in the hills to the south of the city from Kilakee as far south as Roundwood and across a swathe of villages north of the city from Raheny as far west as Blanchardstown.

On the early morning of August 6th 1922, over 200 IRA volunteers were mobilised to destroy all the roads and bridges leading into Dublin city.

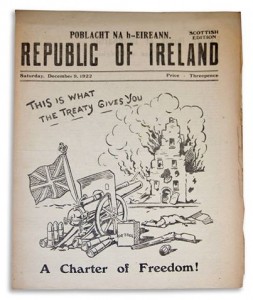

They were volunteers of the anti-Treaty IRA, dedicated to defending, as they saw it, the Irish Republic declared in 1919 and bringing down the Irish Free State, the self governing Irish dominion set up under the Anglo Irish Treaty.

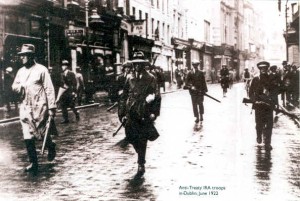

Dublin 1922, a city at war with itself

Dublin in the late summer of 1922 was a city at war with itself.

In late June of that year, rival factions of the Irish Republican movement – supporters of the Provisional Government set up under the Anglo-Irish Treaty and their anti-Treaty or republican opponents, had come to blows. The latter had ensconced themselves in the Four Courts, centre of the Irish legal system and various other strongholds around the city. Pro-Treaty troops, under the command of Michael Collins, blasted them out of their positions with borrowed British artillery.

The pro-Treaty forces had come under intense British pressure to face down the anti-Treaty IRA, but also saw themselves as the legitimate Irish government, legitimised in an election in June of that year, giving them the right to defend the Irish Free State established by the Treaty. Some 65 people had died in the fighting in Dublin before the republicans, or as their foes called the ‘irregulars’, surrendered and some 400 republicans were taken prisoner.

Fighting raged in Dublin for a week in early July 1922 as pro and anti Treaty factions came to blows, sparking off the Irish Civil War

The Irish Civil War, a fratricidal conflict between Irishmen, and very largely between former comrades, had begun. The anti-Treaty forces held most of the south of the country and in August a determined assault, mostly by way of seaborne landings, was made by the Provisional Government on their self styled ‘Munster Republic’.

But even in Dublin, the war was not over. The anti-Treaty IRA there had taken a severe blow in the July fighting but it was not eradicated from the city. It was the last week in July before the guerrillas managed to reconstitute themselves in Dublin, but when they did they launched a flurry of attacks on Free State troops in the streets.

In that week alone (July 21st to 31st 1922) there were 8 people killed in the Irish capital. Admittedly four of them were killed accidentally (two Free State soldiers, a British soldier and a civilian were shot dead while cleaning or handling weapons) but the republicans also mounted almost daily attacks. A sniping attack on Wellington Barracks on July 21st killed an unfortunate civilian passerby for instance, while gun attacks on National Army posts across the city seriously injured another on the same night. [1] On the 25th a grenade attack on troops at York Street missed the troop lorry it was intended to hit but wounded six civilians.[2]

The pro-Treaty or National Army, many of whom, about a year earlier, had been IRA guerrillas launching identical attacks against British troops pondered how to enforce security in the capital, one writing on July 26th , ‘Would it be worthwhile to put a small post on the ‘Dardanelles’ [Aungier Street]. You remember how we often used it for ambushing cars in former times?’[3] .

The Free State’s Intelligence services in the Criminal Investigation Department – a plain clothes unit based out of Oriel House – and National Army Intelligence, uniformed and based out of Wellington Barracks but otherwise much the same, raided houses across the city to arrest anti-Treaty militants. Both units were largely staffed by veteran of Michael Collins Squad and Intelligence Department and therefore had extensive knowledge of the IRA’s personnel and safe houses.

Ernie O’Malley, commander of the IRA’s Eastern Division reported;

‘The arrest of senior officers has generally played havoc with this command. Harry Boland who is acting QM [Quartermaster], and the D/I [Director of Intelligence] have been arrested last night. Harry was shot through the spine and stomach….Michael Carolan Adjutant of 3rd Northern Division [Belfast]…was wounded on Grafton Street. They seem to be concentrating on officers. The result will be that the Brigade here will be without officers.’[4]

Boland died of his wounds; the first of what would be at least 25 targeted killings of anti-Treaty fighters in Dublin. Carolan later recovered [5]

O’Malley had control over the IRA in Dublin only in the vaguest sense. He lived a clandestine life in an upper middle class neighbourhood and communicated to his guerrilla commanders through typed reports delivered mostly by female activists to men on the run either in the city or the nearby hills. In turn O’Malley reported back to IRA Chief of Staff Liam Lynch. But most operational matters were, of necessity, left to local initiative. With the constant arrests of IRA officers, O’Malley was not optimistic of getting a high intensity campaign up and running in Dublin but nevertheless moved in cash and weapons from elsewhere in the country in to Dublin to try to do so.

Isolating Dublin

The IRA in Dublin were realistic enough to know that militarily they could not oust the pro-Treaty forces, or indeed the remaining garrison of 6,000 British troops, from the Irish capital, but with a Free State expedition due to attack Cork city from the sea, the Republicans planned to cut communications to and from the Irish capital.

What became known as the ‘Bridges job’ in IRA circles appears to have been an attempt by the anti-Treaty force to isolate Dublin – the centre both of the Provisional government and its National Army. According to the Irish Times, ‘The Irregulars [republicans] had made elaborate preparations to cut the railway lines and block the roads by blowing up bridges on Saturday night. Men fully equipped were sent to the city from the south and from Liverpool’.[6]

The anti-Treaty IRA in Dublin knew they were too weak to take back the city from the Provisional government so intended to isolate it by destroying and blocking the routes in and out of the capital.

Had the plan come off it may or may not have tilted the military balance of the war in the anti-Treatyites’ favour, realistically more depended on how fighting went in Cork, where Free State troops had landed by sea and assaulted the republican ‘capital’. But had it been successful the ‘bridges job’ would certainly have put the Provisional Government in a more vulnerable position – unable to send reinforcements or communications to its units around the country.

Contrary to what the Irish Times thought, the bridges job was a Dublin affair, not an elaborate plan involving Munster IRA units shipped in via Liverpool. According to Sean Prendergast of the anti-Treaty IRA 2nd Dublin battalion (in the north of the city)

‘The main object of the plan was to blow up and destroy all the canal and railway bridges surrounding Dublin in order to interfere with and interrupt road and railway communications between Dublin and other parts of the country; in other words to hit a fatal blow at the Free State forces in their conduct of military operations against the I.R.A. It appears that on the night appointed for carrying out of the operation, several hundred men of the I.R.A. had been mobilised.’[7]

The risks of mobilising so many poorly armed guerrillas in large numbers at the same time were obvious. The previous year, while fighting the British, the IRA had burned the Customs House in the centre of Dublin, but in the process lost nearly a hundred men (5 killed and 80 plus captured), nearly crippling the organisation in the city.

According to another republican fighter, Liam Nugent of the Third Battalion (south side);

‘a meeting of staff officers was held … to make arrangements for the destruction of bridges in the outlying districts around South Dublin. I strongly opposed this proposal, but the decision was taken and the operation had to be carried out. It fell to the Q.M. [Quartermaster] Dept. to get the explosives and other material to safe places on the south side of the canal. This ended our part in the operation. The whole Battalion, armed and unarmed, were mobilised’. [8]

The Government however, already knew about the ‘bridges job’ due to the capture of Liam Clarke, an IRA Intelligence officer the day before. According to Nugent;

‘The operation was to take place at a given time on a Saturday evening but on Friday evening Liam Clarke, a Headquarters officer, was captured in Rathfarnham with a map showing the bridges to be destroyed, and on Friday the Stanley Street workshop of the Dublin Corporation was raided and picks taken away. Also, the Free State Army authorities had had information that the operation was about to take place’. [9]

There were at this time roughly 4,000 National Army troops in Dublin and another 6,000 British troops who were due to stay in the city until December to ensure the implementation of the Anglo-Irish Treaty. In addition there were about 100 CID plain clothed, armed detectives. Though it did not publicise the fact, the pro-Treaty government mobilised both British and Irish troops in large numbers to avail of the opportunity afforded to decapitate the IRA in Dublin.

The Bridges job

Roughly speaking there were two separate IRA operations on the night of August 5-6th. One was in the Dublin Mountains south of the city, where perhaps 100 Volunteers turned out to dismantle the roads and bridges that connected the city with the guerrillas’ hideouts in the hills. Another 146 anti-Treaty fighters[10] were mobilised in what were then rural villages north of Dublin to destroy the road and rail infrastructure there.

A puzzling aspect of the whole affair though is that the main roads and railway bridges connecting Dublin with the rest of the country lay to the west of the city, notably the road and railway lines through Maynooth and Naas in County Kildare. If the plan was to isolate Dublin these would have been far more significant targets than either the northside or southside operations, but they do not seem to have been included in IRA plans.

Free State troops captured an IRA intelligence officer the day before the ‘bridges job, and knew exactly what the IRA had planned.

In any case, no sooner had the IRA parties begun their work of destruction than they were pounced on by pro-government troops. Sean Prendergast remembered with chagrin that at Cabra bridge on the northside,

‘To their (the I.R.A. men’s) utter surprise and dismay the Free Staters had complete control of the scene; an armoured car patrolling the area, opening fire right, left and centre at point blank range. Bob Oman like a number of other men of the “First” [battalion] was caught while moving along to the scheduled spot. Thus many men were trapped; the men in the fields being pinned down to the point of utter frustration, the men who were making their way thither chased or captured, some quite easily and others after a grim fight, many of them like Oman quite invaluable officers and men.[11]

Across the north Dublin countryside, British and Free State troops rounded up the lightly armed ‘irregulars’ with ease and minimal casualties. Twenty five were captured at Cabra and another ten near Santry with 15 more at Donneycarney and 8 more elsewhere after only minimal resistance.[12]

On the south side it was a similar story. Pro-Treaty troops drove out to the village of Enniskerry, about 20km south of the city and, like hunters ‘beating’ their prey towards a trap, worked their way back over the hills towards Dublin, capturing parties of anti-Treaty fighters in the act of destroying roads and bridges.

On both north and south sides of the river Liffey, Free State troops in some cases back up by British forces rounded up dozens of anti-Treaty fighters.

Thirty one ‘Irregulars’ were captured in Glencullen, including their officer Noel Lemass, and 15 more taken on the roads back to the city, with another ten picked up further south near Roundwood.[13]

According to Liam Nugent, the IRA officers,

‘in charge of the proposed destruction of the bridges were warned’ [that the operation had been compromised], ‘but they insisted on carrying on and, when the various companies arrived at the scenes of action, the Free State soldiers were waiting for them. Some succeeded in escaping but they were nearly all captured. The Republican section of the 3rd Battalion were almost wiped out. [14]

National Army troops also conducted house-to-house searches in the nearby seaside town of Bray, arresting another 30 men.

The pro-government Irish Times reported, “The thoroughness of the intelligence, observation and military organisation on the part of the [National] Army is shown by the fact not only was the destruction prevented so that not even one bridge was destroyed, but the greater bulk of those who were to take part in the irregular operation were made prisoners without any casualties among the troops.’[15]

In fact there were 2 anti-Treaty fighters wounded in exchange of fire but there was no disguising the fact that IRA fighters had shown little stomach for a fight and more than enough willingness to surrender. True, they were outgunned. They were armed at best only with hand guns and homemade grenades (the Dublin Brigade’s rifles and submachine guns seem to have been hoarded for other ‘jobs’) and the enemy had machine guns rifles and armoured vehicles. Frank Henderson, commander of 2nd Battalion reported to Erne O’Malley that,

‘[We were] attacked on both flanks by British and F.S. [Free State] troops who were cooperating. Our troops engaged them but the others, having the advantage of machine guns and superior numbers of rifles, forced them to retreat… The enemy was very strong in armoured cars, armour plated cars and lorries which patrolled the whole area over which the battalion was ordered to operate. This meant it was practically impossible for our men to proceed with their work. The machine gun fire was particularly heavy’.[16]

However, even taking into consideration the disparity in arms, the combat performance of the anti-Treaty units was crushingly weak. There were no last stands in the ‘bridges job’, no sacrificial rearguard actions, in most cases the republicans simply put up their hands and surrendered – indicating that perhaps even at this early stage, their hearts were not in the civil war.

In the early hours of the morning there were a flurry of retaliatory IRA attacks in the city; Firing broke out at military posts, where ‘heavy fire was returned’, including at Mountjoy Prison , Phibsborough, Finglas, Drumcondra and Harcourt St (where a bomb was also thrown). The morning saw six civilians admitted to hospitals in Dublin with bullet wounds along with two anti-Treaty fighters and one National Army soldier, but the attacks had been no more than a futile gesture on the IRA’s part after the disaster of earlier in the night.[17]

Aftermath

The ‘bridges job’ was a disaster for the anti-Treaty IRA in Dublin and it coincided with the fall of Cork city and the main towns in County Kerry, a few days later, to pro-Treaty troops.

In all 187 IRA fighters were captured, two of whom were shot and wounded. Free State forces had just one man slightly wounded in the operation.

In Dublin National Army reports filled up with the names of prisoners taken in abortive attempt to isolate Dublin; 187 names in all were logged between August 5th and 13th. One entire Active Service Unit of Fianna boys (the IRA youth wing) was captured, two of whom were released, no doubt due to their age, but 17 more were imprisoned. Another 6 of the prisoners were from Belfast, presumably having fled south in May to avoid internment in Northern Ireland. Of the rest the vast majority were from Dublin or neighbouring County Wicklow. By the end of August the ‘bag’ of captured republicans in Dublin city was up to 310.[18]

The prisoners were first taken to Wellington (shortly to be renamed Griffith) Barracks to be processed and questioned and then sent in batches to prisons at Mountjoy and Kilmainham in Dublin, Maryborough (now Portlaoise) or the internment camps at Gormanston in Meath and Newbridge, County Kildare.[19]

One of the IRA officers to be captured, Noel Lemass later escaped from imprisonment and fled to England. When he returned to Dublin in mid 1923 he was assassinated, it is thought by undercover pro-Treaty forces. His brother Sean went on to be a long serving Taoiseach (prime minister) of Ireland.

This was by no means the end of the Irish Civil War, in Dublin or elsewhere. It would grind on in increasingly bitter low level violence for many months. But the failure of ‘bridges job’, was in many ways a portent of the republicans’ inevitable defeat. Poorly armed, with a faulty intelligence system and facing an enemy in their former comrades who knew them well, the odds were stacked against them from the moment the first shot was fired in the civil war.

Above all though, as the supine surrender of so many men in Dublin on the night of August 5-6 shows, they lacked the will and motivation to fight an effective guerrilla campaign. It was this above all that guaranteed their eventual defeat.

Discussed here

References

[1] Irish Times July 22 1922

[2] Irish Times July 26 1922

[3] National Army Civil War reports, Dublin Command, Military Archive Cathal Brugha Barracks cw/ops01//03/02

[4] Ernie O’Malley to Liam Lynch, 31 July 1922, (in Dolan, O’Malley , ed.s ,No Surrender Here! Ernie O’Malley’s Civil War papers, P80

[5] Strangely enough though, Carolan is listed as being killed in the republican memorial, The last Post (1985), but he pops up also in Ernie O’Malley’s correspondence as having recovered from the wound and resumed work as an Intelligence Officer.

[6] Irish Times Sat, August 12 1922

[7] Sean Prendergast Bureau of Military History (BMH) WS 802

[8] Liam Nugent BMH WS 907

[9] Liam Nugent BMH WS 907

[10] The figure is Frank Henderson’s commander of the IRA 2nd Dublin Battalion, in his report to Ernie O’Malley, 30 August 1922, (in Dolan, O’Malley , ed.s ,No Surrender Here! Ernie O’Malley’s Civil War papers, p132)

[11] Sean Prendergast BMH

[12] Frank Henderson to Ernie O’Malley, 30 August 1922, (in Dolan, O’Malley , ed.s ,No Surrender Here! Ernie O’Malley’s Civil War papers, p132)

[13] Irish Times August 12 1922

[14] Liam Nugent BMH

[15] Irish Times August 12, 1922

[16] Frank Henderson to Ernie O’Malley, 30 August 1922, (in Dolan, O’Malley , ed.s ,No Surrender Here! Ernie O’Malley’s Civil War papers, p132)

[17] Irish Times August 12, 1922

[18] National Army list of Prisoners taken in Dublin, Military Archives, Cathal Brugha Barracks, cw/p/3/5

[19] Ibid.