The Irish Volunteers of the Eighteenth Century: Successfully Importing the Gun into Irish politics.

By Ruairi Nolan

The Volunteers of the eighteenth century were a group which embodied a rising Irish nationalism which predated that which we associate Irish reform, radicalism and independence.

The Volunteers alongside Grattan’s Patriots embodied the philosophy of William Molyneux, Jonathan Swift and Charles Lucas – Ireland was a political entity, ruled by the British king and independent of Westminster parliament.

The Volunteers had by the 1780s mobilised a significant political influence and utilised their position as a civil defence apparatus to leverage that influence and ultimately in the words of one historian, imported the gun into Irish politics.

Ireland in the eighteenth century

Ireland in the eighteenth century was one of unadulterated submission in the face of the Ascendancy elite, with the minority ruling the majority. Following the conclusion of the Jacobite-Williamite Wars of 1689-91, the powers that be, were determined to create a polity which could not be contested in any way, by the Catholic majority.

From 1695, the Irish Parliament began introducing strict Penal Laws which restricted the rights of Irish Catholics, in terms of religion, education, careers and much more.

Over the course of the century, Ireland was treated as a quasi-colony – it had limited freedom through an assembly, but could achieve little without the well wishes of Westminster and the Privy Council thanks to the Declaratory Act of 1719. Its trade and economy were restricted in the same as other colonies by the Navigation Acts, which allowed the importation of English goods tariff free, but imposed tariffs on all Irish exports, making the Irish economy less competitive.[1]

Ireland in the 1700s was ‘quasi-colony’ of Britain and dominated by the ‘Protestant Ascendancy’

Over the course of the century, Ireland was also viewed by both Britain and its enemies, as a military weakness. On Many occasions, since the Tudor reign, fears of foreign invasion by way of Ireland had piqued the interests of paranoid monarchs and ministers alike from the Spanish in 1588 and 1601, to fears of French involvement in 1688 and 1745, the eighteenth century proved no different. As a result of both the enemy within, and the enemy without, Ireland came to hold a disproportionate quantity of regimental troops during this time, and during periods of conflict where concerns of foreign invasion were the highest, the government funded the formation of local militia groups to supplement this force further.[2]

By the 1770s and the outbreak of the American Revolution, permission was granted for the redeployment of many of those troops stationed in Ireland. By 1778, with the entry of France into the war, hopes for a peaceful resolution of the war anytime soon were dashed, and the economic instability it brought created a sense of vulnerability among the propertied classes.

Attempts were made to create a militia based on previous models under government funding and approval, but the Dublin Government were in no mood to make the necessary funding available. Thus, what followed was the creation of independent militias, following two strains of origins. Their primary focus was to provide a civil defence force, one which would serve to replace garrisoned troops which had been shipped off to fight in the American war – they were to be the line of defence in the event of a French invasion during Britain’s time of weakness. When no invasion was forthcoming, they largely served to supplement local policing and resolve general disturbances.

Emergence of the Volunteers

In the south-east, local paramilitary groups were formed in response to consistent agrarian disturbances, primarily from the Whiteboy groups – a secret Irish agrarian organisation in 18th-century Ireland which defended tenant-farmer land-rights for subsistence farming.

The other is the Volunteers of Belfast, an organisation of democratic structure – all of its officers were elected by the rank and file – it is this Belfast grouping which came to lay the groundwork and set a benchmark for following groups which began to shoot up across the Kingdom.

They differed from standard militia organisations in that they adopted special uniforms and distinctive emblemata. The Belfast Corps, when formed, also made clear their independence, drawing up a statement asserting its freedom from government funding and control, and enough Corps followed their lead to acquire a philosophy of independent armed service.[3]

The Volunteers originally emerged as a volunteer defence force to guard against foreign invasion as British troops left to fight the war in North America

Their aim was to train their members in local defence in the event of an invasion.[4] By the end of 1779, the threat of French invasion, one which had become very real aided in swelling the ranks of the Volunteer Corps across the Kingdom – between Spring and Winter 1779 their numbers rose from 15,000 to 40,000 members – and it is at this point that the Lord Lieutenant officially recognized them and their utility, releasing large amounts of arms for their use.[5]

Until this point, a lot of people of a more moderate political disposition looked on the Volunteers with trepidation, and were uncomfortable with such a significant armed force existing without any government restraint. Once the Lord Lieutenant gave his blessings, recruitment increased further, drawing on many of those who were initially hesitant.[6]

A Working Relationship

At the same time, over the course of the 1770s, a grouping which came to be known as the ‘Patriot Party’ in the Irish Parliament had begun to rise in prominence. While the catholic majority were dominated by the Protestant minority – these ‘patriots’ came to grow frustrated with the domineering relationship England held over Ireland and its ascendancy.

Its membership had fluctuated over the course of the 1770s-80s but from 1779-1782 their importance had grown disproportionately to their numbers. The bulk of non-government MPs had begun to side with Patriot initiatives.

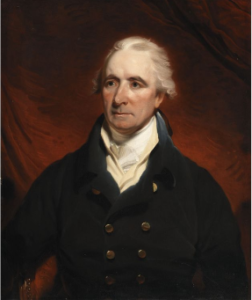

This appears to not have been for any specific patriot affinities, but rather many sought to take advantage of the political uncertainties created by the worsening American conflict, and the Patriot opposition offered a ready-made justification for doing so.[7] One can also find a significant cross section of Volunteers and Patriot politicians – some examples include Henry Flood, Henry Grattan and the William Robert Fitzgerald, 2nd Duke of Leinster.

The Volunteers became allied with ‘Patriot Party’ who advocated reform of Irish society and greater independence from Britain.

When it became clear that no invasion was forthcoming, the Volunteers began to look home-bound and affect political change. As mentioned, initially many were cautious about having such a significant extra-parliamentary body, ungoverned and unregulated – but as time went by they were looked on with respect and honour.

The political potential of such a large and well organised movement was not lost on some though, as historian Tom Bartlett said ‘the Volunteers had successfully imported the gun into Irish politics’.[8] The Volunteers developed into political clubs of sorts, each forming its own debating society. They became breeding grounds for progressive and enlightenment thought, and they came to use their influence to press the government for reform.

The Volunteers’ demographic was largely Protestant only, in keeping with the Penal Laws which restricted both Presbyterians and Catholics from arming themselves. Following the Nonconformist Relief Act 1779 which allowed any Dissenter to preach and teach on the condition that he declared he was a Christian and a Protestant and took the Oaths of Allegiance and supremacy, presbyterian membership rose.

Over the course of 1779, the Volunteers and the Patriot contingent within the Irish Parliament formed what P.D.H. Smyth considered a ‘working relationship’. It was a relationship rare in the politics of any country at the time and certainly unique in Ireland for the cooperation between an armed force and a representative assembly.[9] Suddenly Great Britain was facing trouble on two fronts, at the furthest reaches of the empire and on their own front door – it is an example of that old adage, ‘Britain’s difficulty, is Ireland’s opportunity’.

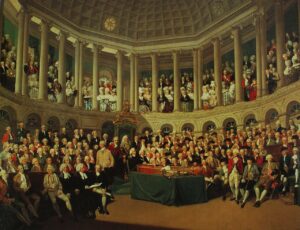

What the Volunteers allowed for was pressure by demonstration – utilising their numbers in parades and marches to show officials the military strength they could muster if ever it was felt necessary. In Dublin on 4th November 1779, they demonstrated outside the House of Parliament on College Green, for removal of restrictions on Irish trade with Britain; with banners hanging from artillery guns proclaiming ‘Free Trade or this’, referring to their cannon and ‘Free trade or a Speedy Revolution’.[10]

Acknowledging this new domestic presence as a threat, the Navigation Acts in Ireland were repealed, allowing Ireland and Irish merchants to trade freely within the empire except for regions under the monopoly of the East India Company. This victory served as an indicator to others in the Irish parliament that change was possible, a piece of the imperial armour keeping Ireland artificially weaker had chipped.

A coalition of Patriot and independent MPs agreed in the Spring 1780 to strive for three basic constitutional reforms – a new Declaratory Act in order to make clear that the crown and the Irish parliament alone were capable of making laws for the kingdom to functions, modifications to Poynings Law so as to remove the ability of the Irish privy council and the Lord Lieutenant to participate in the framing of Irish law, and an Irish Mutiny Act in order to make the army regiments stationed on the island of Ireland accountable to the Irish parliament on terms identical to those already established in Britain.[11]

It is important to note however that many MPs viewed the utilisation of the Volunteers as a show of force, as a ‘one and done’ tool. They were queasy about the idea of further intervention and feared giving too much power to such a body. It is clear that the Volunteer Corps’ remained conscious of this, and remained steadfast in their role as political operatives and its relationship to parliamentary process. During the prorogation of Parliament of September 1780 to October 1781, the Volunteers remained resolutely silent about political matters, until parliament reconvened.[12]

Towards a New Constitution

Throughout the winter of 1781-2 the political climate had changed rapidly and the Volunteer Corps saw yet another surge in membership, reaching their zenith at 80,000 and had begun to declare support for various Patriot proposals for reform. This was all taking place in the face of a crumbling North Administration led by Frederick North, 2nd Earl of Guilford, which had governed Britain since 1770, overseeing the now deteriorating American Crisis, greater economic autonomy in Ireland in 1778-9, and the Gordon Riots of 1780.

By the autumn of 1781, the British in America were forced to admit defeat following the surrender of Lord Cornwallis at Yorktown and the American colonies had managed to successfully break away from British control. The Volunteers were openly called on by Patriot MPs frustrated by the government majority in parliament and at a large meeting of Southern Ulster Corps in Armagh in late 1781, a call was issued for a convention to be held with representatives from as many Volunteer Corps as possible to consider ‘vigorous and effectual methods to root corruption and court influence out of the legislative body’.

Armed, though peaceful, demonstrations by the Volunteers helped to secure the ‘constution of 1782’

This meeting of 140 Volunteer delegates at Dungannon produced a concrete but radical manifesto for constitutional change which mirrored Patriot demands – an open call for legislative and judicial independence.[13]

With the eventual fall of the North Administration in March 1782, Henry Grattan refused to agree to a stay on parliamentary debate for the interim period. He called for the formal declaration of Ireland as a distinct kingdom, capable of administering itself independent of Westminster – the fall of the North administration should have no bearing on the ability of Dublin to govern itself under the tutelage of the king (echoing the sentiments of William Molyneux in his 1698 The Case of Ireland).

Grattan also reiterated calls for a repeal of the 1720 Declaratory Act and a rewrite of Poynings Law. Within the space of three months, the new administration in London, feeling itself in no position to contest with the demands, acquiesced – in addition another Catholic Relief Bill was passed building on the previous 1778 one.[14]

The constitution of 1782

The ‘constitution of 1782’ granted the Dublin parliament effective independence with regards to its economic and legislative abilities. Dublin Castle authorities and Westminster lost the ability to outright veto Irish legislation and make changes to it. The ultimate authority still remained with the monarch – retaining the royal veto over Irish legislation and maintaining the ability to appoint the royal executive, the Lord Lieutenant. The 1782 changes did not amount to self-government, but instead D. George Boyce argues that it would be better described as self-legislation, capable of introducing its own laws, the Dublin parliament remained an extension of Westminster and the King, who ultimately had the final say.[15]

The ‘constitution of 1782’ granted the Dublin parliament effective independence with regards to its economic and legislative abilities, after which many Volunteers felt their political aims had been met.

With these concessions, many who fell in behind both the Patriots and Volunteers felt satisfied with their lot, feeling it unnecessary to go any further. There did remain though, many who wanted to go further, musings of full catholic emancipation and more radical political reform began to circulate. The ideas of annual parliaments, wider enfranchisement and redistricting of boroughs entered discussions, but by this point many moderates had started to become disillusioned with further reforms.

Splits began to emerge within the Volunteers and in 1783 there were further attempts to press the issue of reform on the Dublin Parliament. After a convention held in Dublin on 29th November 1783, Henry Flood marched to College Green and presented their new manifesto for reform including resolutions such as annual parliaments, and the redistribution of parliamentary seats, but having attended the house in his Volunteer uniform he was met with resolute indignation from MPs who ‘refused to register the edicts of another assembly, or to receive proposals at the point of a bayonet’.[16]

The following day the Dublin parliament voted not to receive the bill Flood had put before it. It later introduced and passed two resolutions declaring that the house would maintain its just rights and privileges against any encroachments from other extra-parliamentary assemblies and another expressing its perfect satisfaction with the current constitution and state of affairs in the Kingdom of Ireland.

This episode marked the end of the working relationship between the Volunteers and parliament and similarly marked a divide which had formed amongst the internal politics of the Volunteers between Grattan and Flood. While Grattan voted to receive Flood’s bill, he also voted in favour of the subsequent resolutions, making any call for further reform null and void.[17] Also in April 1782, following the achievement of legislative freedom, and acknowledging the dangers posed by the Volunteers, Grattan noted that he praised the order and discipline of the volunteers but now asked them to ‘leave the people to parliament, and thus close, specifically and majestically, a great work, which will place them above censure and above panegyric’.[18]

Volunteering continued to persist throughout the rest of the 1780s though it took on a much more local and less influential role. It remained a pastime of sorts, a political outlet for debating ideas and theories but little else. Its presence was most persistent in Ulster, and it remained an Ulster phenomenon.

It would recede into the background as the 1780s brought relative peace to both Britain and Ireland, and it would not be until the outbreak of the French Revolution that we see a resurgence in Volunteering, mainly in the north, and particularly in Belfast. The Volunteer Corps were central to celebrations of Bastille Day in Belfast in 1791, planning for which involved a number of future United Irishmen, and which led to a more organised and distinct celebration in 1792.

The Volunteers were but one facet of Irish politics during an era which saw a widening of the parameters to political participation. As the century drew on, the popularisation of politics only grew further. The Volunteers proved to be but a vehicle for the Patriots in parliament, and allowed for intimidation of a kind which grew unpalatable even to those Patriots who sought most to use them. Grattan said it best when he indicated that the threat of violence, was best used once, and once alone.

The Volunteers would recede into obscurity, but they remained, in Ulster a form of political participation for a select few, as an outlet for debate and political engagement – it was but one form of a political club which, like many others saw a resurgence with the outbreak of revolution in France in 1789, and which ultimately faced suppression from the government in 1793.

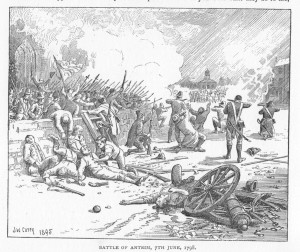

Some of the more radical Volunteers later joined the revolutionary United Irishmen, while the more conservative retreated into support for the Government and the Ascendancy in the rebellion of 1798.

The Volunteers of the 18th century launched a paramilitary tradition which would influence future generations of political opposition. The Volunteers of the 18th century set a precedent for using the threat of armed force to influence political reform. In 1912 and 1913, the formation of the Ulster Volunteers and the Irish Volunteers drew heavily on the legacy and impact of their 18th century namesake – their legacy became but another aspect of Irish history, divided by contemporary sectarian and cultural divisions.

Bibliography

Allan Blackstock, Double Traitors? The Belfast Volunteers and Yeomen 1778-1828 (Belfast, 2000).

- George Boyce, Nationalism in Ireland (London, 1995).

David Dickson, New Foundations: Ireland 1660-1800 (Dublin, 1987).

Gerard O’Brien, Anglo-Irish Politics in the Age of Grattan and Pitt (Dublin, 1987).

J.C. Beckett, The Making of Modern Ireland 1603-1923 (London, 1966).

Marianne Elliott, Partners in Revolution (London, 1982).

P.D.H. Smyth, ‘Volunteers and Parliament, 1779-84’ in D.W. Hayton and Thomas Bartlett (eds), Penal Era & Golden Age – Essays in Irish History 1690-1800 (Belfast, 1979).

Thomas Bartlett, ‘This famous island set in a Virginian sea’: Ireland in the British Empire, 1690–1801’ in P. J. Marshall (ed.), The Oxford History of the British Empire: the Eighteenth Century (Oxford, 2001), pp 253–275.

Notes

[1] Marianne Elliott, Partners in Revolution (London, 1982), p. 10.

[2] David Dickson, New Foundations: Ireland 1660-1800 (Dublin, 1987), p. 164.

[3] P.D.H. Smyth, ‘Volunteers and Parliament, 1779-84’ in D.W. Hayton and Thomas Bartlett (eds), Penal Era & Golden Age – Essays in Irish History 1690-1800 (Belfast, 1979), p. 114.

[4] Dickson, New Foundations, p. 164.

[5] Ibid., p. 165.

[6] Smyth, ‘Volunteers and Parliament, 1779-84’, p. 115.

[7] Gerard O’Brien, Anglo-Irish Politics in the Age of Grattan and Pitt (Dublin, 1987), p. 26.

[8] Thomas Bartlett, ‘This famous island set in a Virginian sea’: Ireland in the British Empire, 1690–1801’ in P. J. Marshall (ed.), The Oxford History of the British Empire: the Eighteenth Century (Oxford, 2001), pp 253–275, p. 267.

[9] Smyth, ‘Volunteers and Parliament, 1779-84’, p. 113.

[10] Allan Blackstock, Double Traitors? The Belfast Volunteers and Yeomen 1778-1828 (Belfast, 2000), p. 4.

[11] Dickson, New Foundations, p. 168.

[12] Smyth, ‘Volunteers and Parliament, 1779-84’, p. 121.

[13] Dickson, New Foundations, p. 169-70.

[14] Ibid., p. 171.

[15] D. George Boyce, Nationalism in Ireland (London, 1995), p. 113.

[16] J.C. Beckett, The Making of Modern Ireland 1603-1923 (London, 1966), p. 231.

[17] Ibid., p. 232.

[18] Boyce, Nationalism in Ireland, p. 114.