Book Review: Radical Basque Nationalist-Irish Republican Relations, A History

By Niall Cullen

By Niall Cullen

Published by Routledge, 2024

Reviewer: John Dorney

Minority national causes have often looked to each other for inspiration and education. It is also common for those with a sense of national struggle, to see their cause and themselves, reflected in other countries, as perhaps we can see with Irish identification with the Palestinian cause today.

In this thoughtful, well-balanced and very well researched book, Niall Cullen explores the historical and contemporary links between Irish and Basque nationalists, particularly between the militants; Irish republicans and Basque radical nationalists. The two movements came to see each other as close friends and even co-belligerents in recent decades, but it was not always so.

Cullen’s focus here is not so much on abstract comparisons between the two cases but rather on concrete links – ‘talking to’ rather than ‘talking about’ each other, as he puts it.

Origin myths

The book opens with consideration of ancient origin myths concerning the mythical flight of the original Irish the ‘Milesians’ from what is now the north of Spain to Ireland.

The story quickly moves on, however to the late nineteenth century, when modern Irish and Basque political movements emerged. Irish nationalism was arguably of longer standing, but Basque nationalism, expressed as such, only appeared in the late 1800s after the region’s traditional autonomy or Fueros were abolished by the Spanish state.

For some time, the conversation about comparisons between the two were mostly one way. Ireland was prominent in world discourse because of its place as a mostly English-speaking country, connected to the most powerful empire of the day.

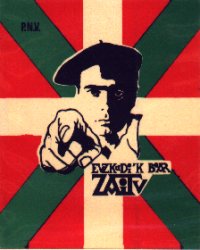

Thus, Cullen tells us, there were some mentions by Basque nationalists in the nineteenth century of the Irish struggle, but not they were not widespread. Mainstream Basque nationalists of the PNV (Partido Nacionalista Vasco), who aspired to autonomy within the Spanish state, admired the pursuit of Home Rule and the constitutionalism of John Redmond and initially condemned the violence 1916 Rising in Ireland.

Civil Wars

However, the more radical aberriano (‘patriotic’) wing of Basque nationalism under Eli Gallastegi admired the Easter Rising – and the Irish republican struggle of subsequent years. Gallastegi, known as ‘Gudari’ or ‘soldier’ later became a political refugee in Ireland.

While Cullen debunks the idea that the 1916 Rising was the inspiration for the Basque national day, Aberri Eguna, also on Easter Sunday, it is clear that the Irish independence struggle had become an inspiration for Basque separatists by the 1930s.

Moving in the other direction, Cullen also introduces us to the Irish-Argentinian republican Ambrose Martin, who was in Basque country during the Irish revolutionary period (1916-23) and was again in contact with the Basque nationalists during the Spanish Civil War (1936-39). Martin made some attempt to attract sympathy for the Basque cause in Ireland but the Irish Republic of 1919-21 was more interested in propaganda in Spain as a whole and possibly securing recognition of the self-declared republic.

Basque nationalists seem to have interpreted the Treaty split in Ireland from a largely anti-Treaty perspective. However the interest was still mostly one way.

There was however, some sympathy displayed in post-1922 Ireland for the Basques as fellow Catholics and small nationality struggling for independence. This was displayed during the Spanish Civil War by both pro-Franco O’Duffyites and pro-Republican Irish Republicans during Spanish Civil War. Both Irish factions who sent volunteer fighters to Spain were actually more interested in the pan Spanish, rather than the separatist dimension of the war.

Nevertheless, Irish republicans, including the aforementioned Ambrose Martin, brought a Basque priest Ramón Laborda to Dublin to argue that the Spanish republic was not against religion as its enemies claimed. Eoin O’Duffy for his part, initially refused to have his pro-Franco contingent fight against the Basques as opposed to the ‘Reds’, though he later stated that he was mistaken.

The Basque autonomous government, which functioned for nine months until its conquest by Francoist forces in the Civil War in 1937, appear to have hoped for more concrete solidarity from the Irish government itself and its representatives met Eamon de Valera, hoping for military or financial aid. They were disappointed. One outgrowth of the Basque defeat in the Civil War, we learn, was the flight of a small number of Basque nationalists to Ireland, where a small ‘Basque village’ developed in at Gibbstown in Co Meath, housing 12 refugee families. This included the family of veteran nationalist Eli Gallastegi after 1940.

They were among a small community of minority nationalists who washed up in post-war Ireland, having experienced defeat in much wider wars – another group was Breton nationalists including the sculpture Yan Goulet. Quite unlike more recent refugees in Ireland, their presence had an ideological dimension; the Irish state was still seen by some as a refuge and inspiration for minority nationalists, despite it having by now a very unrevolutionary government.

New beginnings

Under the Franco dictatorship, the Basque Country experienced a repression of its language, political parties and even individual freedoms of a ferocity and scale not matched in twentieth century Ireland. Members of its short-lived government and those who fought for it were killed, imprisoned or driven into exile.

Nevertheless, by the 1950s, shoots of resistance were reemerging, from which eventually came the armed group Euskadi Ta Askatasuna (the Basque Country and Freedom or ETA). It is interesting to learn in Cullen’s book that Irish analogies were used by Basques in this period to debate the correct way forward, but lessons to be learned from the Irish example were hotly debated.

Some still found inspiration in Irish history. We read of a speech by Iker Gallastegi (son of Eli) citing Patrick Pearse’s contention that ‘war [for national independence]is not an evil thing’. Though this sentiment was condemned by more peaceable nationalists as ‘fascist’. Some Basque militants appear to have received training from the IRA in 1960. But some, such as the writer Federico Krutwig, cited Ireland as case where political independence had failed because the Irish language continued to contract. The need in the Basque Country, he argued, was to follow more radical examples, such as the armed struggles in Israel, Cyprus and Algeria in the postwar period. Conversely the moderate PNV, we learn, cited the failure of IRA border campaign in 1962 as evidence of the futility of violence.

The group that became ETA was one of many that emerged towards the end of the dictatorship in Spain. It was the most determined and effective user of armed force against the regime however, and first killed, and saw members killed, in a series of confrontations with the Spanish police in 1968. Coincidentally this was much the same time as deadly rioting and civil strife was beginning to break out in Northern Ireland.

Comrades?

Post 1969, both ETA and IRA had new armed conflicts at hand. From this point, Cullen notes, Basque references to Ireland became less a historical comparison to the Irish revolutionary period and more seeking parallels with the contemporary conflict in Northern Ireland.

Cullen lays out the various tortuous splits in ETA, which finally resolved themselves into two main factions, ETA-militarra (ETA-m) and ETA Politico-militarra (ETA-pm). ETA-m prioritised armed struggle for the full independence of the Basque Country while ETA-PM promoted left wing political organisation alongside the armed campaign.

For observers of Irish republicanism post 1969 it does not take a great leap of imagination to see the parallels here with the Provisional and Official versions of the IRA and Sinn Fein. Especially as ETA-PM abandoned the armed struggle in the early 1980s and embarked on a road which eventually led themselves to merge with the Basque affiliate of the Spanish Socialist Party. Oddly however, as Cullen shows, the links made in practice in the 1970s were largely between the Provisional Republican movement and ETA-PM, the less hardline and more left wing of the two ETAs.

In the 1970s there were joint statements between Irish republicans and Basque separatists, we learn and fraternal visits to each other’s conferences, including by the then Sinn Fein president Ruairi O Bradaigh. It is also likely, though as Cullen comments, it is impossible to prove, that there were significant exchanges of hardware and explosives. But as yet, these were only one among a number of international militant contacts the two movements had.

One reason for this was that, for all they had in common, being the last two nationalist-separatist armed conflicts in western Europe, the Basque and Northern Irish conflicts in the 1970s were markedly different in other ways. The conflict in Ireland’s six north eastern counties was defined by the sectarian cleavage there, and arose in 1968-9, not only because of unfinished demands for Irish self-determination, but also because of the desire of the Catholic minority in Northern Ireland for social, economic and political equality.

The modern Basque conflict, by contrast, had its roots in the emergence from the Francoist dictatorship and how Basque demands for self-determination could subsequently be fitted into a new Spanish democracy. While Basques were (and are) certainly divided over the question of whether to pursue independence, these is no hard and fast communal cleavage there to compare with that represented by religion in Northern Ireland. No segregated towns and cities, no ‘peace walls’, no random killings of ‘enemy’ civilians.

Cullen is careful not to endorse such arguments about fundamental differences between the two cases, but he does point out that it was not until the 1980s that the Provisional Republican movement and ETA-M began to see each other as real brothers in arms and their struggles as close parallels. In 1983 for the first time a representative of Herri Batasuna (close to ETA-M) replaced Jose Ramon Penagarikano of EIA (close to ETA-PM) at the Sinn Fein Ard Fheis.

On the One Road

It seems clear that the close relationship between the two developed from the particularly hard-headed positions of the Provisionals and ETA-M respectively. As other forms of separatist and left-wing armed movements in Europe fell away in the 1980s, they were left alone as the last two remaining insurgencies west of the Iron Curtain.

What was more, they became defined in both cases by a refusal to compromise on armed struggle and complete national independence, as they defined it. Denounced by more moderate nationalists, battered by clandestine ‘dirty wars’ by respective British and Spanish states, but still carrying on in both armed and electoral fronts. While the republicans developed the ‘Armalite and the Ballot Box’ strategy, in the 1980s, advancing Sinn Fein alongside the IRA, the Basque ‘patriotic left’ around ETA similarly had the motto beitan jarrai (‘carryon both’) in reference to politics and armed struggle. In a manner quite symmetrical with Sinn Fein’s vote in Northern Ireland in the 1980s, the Herri Batasuna party typically secured about 15-20% of the Basque vote in that decade.

There was almost certainly military cooperation between the IRA and ETA in the 1980s and 90s, also. Most evidence of this, understandably, amounts to rumours, and Cullen is very careful about allegations. But formal military collaboration was proved when a meeting between the two sides in Paris was raided by the French police in 1999, the documents seized showing that the IRA had sold substantial quantities of explosives and handguns to ETA.

The two movements also fed off each other’s sub-cultures. Basque nationalists began to describe non-nationalist Basques as ‘unionists’ aping Irish terminology, while Irish republicans were impressed by the Basque movement’s youth culture and revival of the Basque language. Figures such as Eoin O Broin, today a high profile Sinn Fein TD, were to the forefront of contacts between the two youth movements in the 1990s, we learn.

It seems clear from Cullen’s account that, notwithstanding incomplete information about each other’s cases and sometimes mutual misunderstanding, the solidarity thus engendered between the two was real and lasting. The most poignant illustration of this in Cullen’s book comes when post peace process Sinn Fein, embarrassed in the 2000s by ETA’s resumption of violence, still refused to cut ties with them. One ‘usually very unsentimental republican’ commented according to Sinn Fein’s Pat Rice, ‘but fuck me! They’re good people!’

One comes away with the impression that it was not so much the inherent similarities of the Basque and Irish causes that caused such fellow feeling as the common experience of being an embattled, militant minority in a conflict situation.

Peace Processes

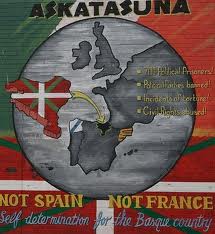

In the 1990s, both movements engaged in peace processes, attempting to resolve their long-standing conflicts. ‘The Irish mirror’ was, Cullen explains, particularly influential in the Basque case, inspiring Basque nationalists and infuriating Spanish conservatives and successive Madrid governments.

This was because the Northern Irish peace talks were kick started by the ‘Downing Street declaration’ of 1993, in which the British government declared that it had ‘no selfish or strategic interest’ in remaining in Northern Ireland and that the future of that entity would be determined by the wishes of its inhabitants. It was also predicated on what unionists in Northern Ireland termed the ‘pan-nationalist front’ in which there was de facto alliance between Sinn Fein, the more moderate SDLP and the Irish government in forwarding nationalist demands.

This formulation, what the Basques termed the ‘Irish mirror’, proved to be explosive in the Basque country. After ETA’s ceasefire of 1998, Basque nationalists, including the traditionally moderate and non-violent PNV, did indeed get together in what was termed the ‘Irish Forum’ , to demand self determination for the Basque provinces in Spain, including the existing Basque Autonomous Community and Navarre.

This provoked fury, not only among diehard Spanish centralists, but among the Spanish Socialist party as well. Some of this did have an analogy with Northern Ireland, mirroring the disgust unionists professed to feel for legitimising ‘terrorists’ who had recently been killing their members and supporters. But it also highlighted some important differences between the two cases.

Northern Ireland was detached enough from the rest of the United Kingdom for London governments to state that they would leave it if the majority so desired. No Madrid government would ever say this about the Basque Country. Nor, as more recent events have demonstrated, about Catalonia for that matter. They were prepared to talk to ETA about release for prisoners in return for an end to political violence, but no more. They would also point out that the majority of the Spanish Basque Country already had extensive autonomy – considerably more than Northern Ireland was given, even after devolution.

But thirdly, ETA themselves deeply misinterpreted the republican strategy in the Irish peace process. Sinn Fein’s leadership had already come to the conclusion by the 1990s that they needed to make a historic compromise with unionism. This was exemplified in the fact that they agreed to two separate referenda in the two states in Ireland to approve the final agreement and agreeing to participate in the institutions of a reformed Northern Ireland. Though the initial IRA ceasefire temporarily broke down in 1996-7, it was rapidly brought back on track once Sinn Fein entered peace negotiations.

ETA’s peace strategy by contrast, was apparently led by hardliners, of the type whose equivalent in Ireland regarded the Adams-McGuinness leadership as traitors. ETA seemed to think that a peace process would advance their maximalist demands of Basque self determination across the historic Basque country in France and Spain. Thus, repeated rounds of talks with Madrid governments (some open, some secret) floundered. ETA attempted in the 2000s to go back to ‘war’, aimed at bringing about a strategic victory, only to find that with increased security pressure on both their armed and political wings and their social support leaking away, they ended with nothing at all to show for their nearly forty year long armed campaign.

Indeed, by the 2010s, several radical Basques ended up effectively as refugees in Northern Ireland, fleeing the Spanish judicial system, under Irish republican protection. This book reminded this reviewer of half-forgotten episodes from this period, such as the attempted extradition of ETA activist Inaki de Juana Chaos, back to Spain from Belfast. Chaos fled Ireland in 2010 and his whereabout have not since been determined.

ETA finally called a final ceasefire in 2011, and announced an end to their organisation in 2018, very much in the manner that the IRA had done in 2005 and indeed under the guidance of senior Irish republicans (and also figures including former Taoiseach Bertie Ahern), but in their case having suffered total defeat. In the end, one could say that the ETA leadership learned very poorly from the ‘Irish model’.

All of this Cullen lays out in this book with great clarity. This is an excellent and enlightening book and a real advance in our understanding of this topic. The text is enlivened by interviews with many of the participants, on both the Irish and the Basque side. It is warmly recommended to anyone with an interest in the Basque Country, Irish republicanism and the links between the two.