Book Review: A Year of Glory and Gold 1932- Ireland’s Jazz Age

By Kevin C. Kearns

By Kevin C. Kearns

Published by Gill Books, 2023

Reviewer: Sylvie Kleinman

ISBN: 9780717195619

Kevin C. Kearns has written a multi-facetted social and cultural biography of the year 1932 in Ireland, interweaving compelling vignettes of daily life as the weeks and months unfolded.

If you seek detailed information about flappers, this otherwise vivacious and sprightly book may partially disappoint jazz fans, due to its unintentionally misleading title. Jazz is the recurrent signifier throughout, a device to embody the many manifestations of modernism in Ireland throughout the year under consideration, but its performance and musicians are not dealt with in detail. The book’s concept is clever, and the outcome a success.

Kevin C. Kearns has written a multi-facetted social and cultural biography of the year 1932 in Ireland

Kearns has already used this format for the year 1963, and here again applies his research expertise as a widely-published social historian, author of over a dozen books on Dublin, and writer of effortless prose. Though most of his material comes from the public domain, Kearns also embeds a few compelling perspectives from ordinary people he had previously interviewed, on various aspects relevant to the year under scrutiny.

For half a century, he went on notable journeys through the streets and tenements of Dublin, recording and preserving their oral history for all times. The thread of A Year of Glory and Gold 1932- Ireland’s Jazz Age is certainly grounded in the nation’s self-awareness of living in an age of ebullient modernity. Its popularising style convincingly demonstrates the fast-paced madness of highly-organised life, post World War I.

Ireland enthusiastically embraced this modernity and in 1932, the Evening Herald lamented the new phenomenon of ‘minus sleep’ afflicting young Irish women. Their life of excessive hustle and noise made them unfit to become wives and mothers, and the GAA adopted a tough stance on jazz dancing at their functions. So free-spirited girls, their hair styled in shingles and mingles, were not alone in emulating jazz band conductors demonstrating shimmy, shag and shuffle moves. The music was foreign, triggered primitive physicality, and even worse. According to the Belfast Newsletter, it demonstrably made monkeys go berserk.

Revisiting the Year 1932

But to many readers, 1932 most obviously kicked off with de Valera’s Fianna Fail election victory, ushering in an unprecedented era in Irish politics, and arguably the nation’s mood. Not risking the loss of votes from the young or less young, Dev had neither endorsed nor criticised jazz culture when campaigning. He affirmed his enduring preference for traditional Irish music and dance, while recognising there was a place for multiple tastes in a modern society.

By no means only an urban and cosmopolitan phenomenon, in many unlicensed all-night dance halls throughout the land, the jazz craze was also fuelled by the scourge of smuggled poteen.

Aiding the frenzied quasi-sexual contortions, this added a legal dimension to moral concerns, and gardaí on revenue duty were dispatched down many a boreen in the wee hours. Poteen raids led to the press covering some ‘comical and unique’ episodes, namely when pigs were involved (in both rural and urban settings).

Not risking the loss of votes from the young or less young, De Valera had neither endorsed nor criticised jazz culture when campaigning for election

Such tantalising juxtapositions of traditional and modern Ireland are peppered throughout this swiftly-paced and highly-readable book. Over thirteen chronological chapters, Kearns tracks how the Irish experienced major or minor public events at local, national or international level throughout the year, some of which had conferred glory on the old sod.

While high political tensions, ongoing sectarian violence, and social concerns are not silenced, they do not drive the narrative. Referencing is light, and quite reliant on the press, but Kearns’s work is not aimed at a high-brow audience. His narrative style is fluid and unpretentious, does not claim to rest his arguments on academic theory, and remains lucid and convincing. Journalistic, participant, observer or eyewitness perceptions prevail. The tone throughout is upbeat and insights from the interviews project memories which would otherwise have been lost.

As no invention had brought more pleasure than the cinematograph, he duly sought out one Robert Hartney, born in 1897 and interviewed 93 years later. He had played a historic role as a junior usher in Dublin’s new Manor Street Picture House when they opened in 1920, showing only silent films until 1929.

For impoverished tenement dwellers, the escapism was actually therapeutic, and perhaps a second-edition of this book could add that the building in Stoneybatter has survived, and is thriving as a community workspace. Cinema was immensely popular, but news that the spine chilling Frankenstein would soon be released in Dublin, as yet not pronounced on by the film censor, sparked a frenzy of ‘anxiety and anticipation’.

Everyone knew about the sensation it had caused in America for its new graphic genre of science fiction horror, and it was banned after only three days in Belfast. The Free State censor James Montgomery followed suit, prompting a cinema manager and film renters to take action. They successfully appealed, arguing that it was manifestly and merely a ‘dream of pseudo-scientific imagination’ and free from ‘any immorality’, projecting quite a sharp and modern mindset.

Eucharistic Congress

In this age of new technologies, newsreels also allowed cinemagoers to partake in a landmark international event held in June in Dublin, which drew the gaze of the world on Ireland. This was of course the 31st Eucharistic Congress, which may not send the pulses running among some devotees of this website, yet few could deny its many-layered meanings.

Affirming an independent Ireland’s Catholicity to the world, it had also required a grand strategy: organised as a military operation, highly successful, unsurprisingly re-asserting to many Northerners the instrumentality of the border, its dissemination at home and abroad could not have happened without aerial photography and the media technology of the age. Yet the book opens with its mystical precursor on New Year’s Eve.

1932, the 1,500 anniversary of Saint Patrick’s arrival in Ireland, had been ushered in with people thronging the roads around Slieve Gullion in Armagh, amazed and astonished at a cross blazing on a hill.

Gold

Gold had impacted on Ireland in two ways. Early in the year and coinciding with the excitement of the election, a new rush was proclaimed, but in these islands and not far-off mines. The value of gold had skyrocketed after Britain left the gold standard in September 1931, and dealers advertisement’s offering to buy led to a veritable mania to cash in. Everyone rushed to find precious items which had been stuffed in religious statues, behind chimneys, or in crevices and crannies.

At a more honourable level, the summer Olympics in Los Angeles brought ‘glorious gold’ on Ireland. Ireland had competed with Great Britain for the last time in 1920, and Dr. Patrick O’Callaghan had won the first Free State gold medal (for hammer throwing) in Amsterdam in 1928. He repeated this feat in 1932, with his compatriot Bob Tisdall not only winning Ireland’s second gold medal, but setting a new world record for the 400 metre hurdles.

Improvised jubilation

Kearns adds an interesting layer to the jubilation that ensued across the land. He references debates about the symbolism of the national anthem and flag, not yet officialised but increasingly deployed with intensifying pride, hence the source of antagonisms.

Again, the sheer scale of the Congress serves as a gateway into compelling anecdotes, regardless of one’s views on the rising theocracy.

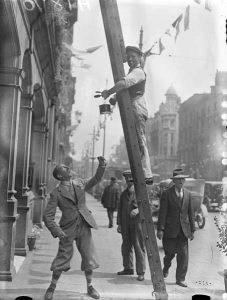

The tricolour may not yet have been embedded in Irish legislation, but by June and the Congress, it was too late. Hundreds of thousand of them were on sale and in all sizes, to fit a toddler’s hands or to ‘cloak the front of buildings’. The enthusiasm and pride of the dispossessed triggered their own creative dynamic, the decoration of their modest abodes.

This is empathetically described, namely for Dublin’s tenement dwellers. Mary Chaney of Smithfield, born in 1906 and interviewed in 1990, recalled how every street in Dublin ‘was done up.’ Though these streets were strategically off the radar of official events, photographers had captured the bunting and holy pictures.

Pity so, not one of these evocative documents was reproduced, and though the book is well illustrated, some photos project the age’s modern mood well, but from America. Oddly, radio is not referenced. The book closes with Maud Gonne MacBride receiving a gold brooch, the Rathfarnham earthquake on Christmas day, and the Evening Herald’s prophecy that future historians would have a lot to say about the wondrous events of Ireland’s new era.

A Year of Glory and Gold eloquently projects reality, humanity, optimism, and fun.

Whether out campaigning, suffering the effects of ‘Hurry’, the ‘bane of life’ in 1932, the self-assertion of women is well captured by the utterly with-it Colleen, beckoning us on the vibrant cover to enter, and enjoy a bit of fishing or a drive in an emblematic Irish landscape. Convincingly teasing out the telling anecdote, Kearns provides entertainingly informative leisure reading, and this book would make an ideal gift. It will no doubt trigger many memories of the experience of these events relayed by older, or now departed generations, some retrievable in the form of photos and memorabilia.

Reflecting the shifts in attitudes towards representations of the past which the Decade of Centenaries has fostered, at both academic level and in works aimed at a popular audience, A Year of Glory and Gold eloquently projects reality, humanity, optimism, and fun. In September 1932, having been appreciated way back by no less than Thomas Moore, Kearns tells us, but associated with America, the yo-yo was demonstrated in Clery’s display window. This late introduction triggered a veritable craze, and undeterred by their relative lack of experience, by November the Irish had already organised no less than a twenty-six county National Championship!