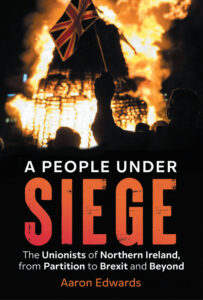

Book Review: A People Under Siege – The Unionists of Northern Ireland, from Partition to Brexit and Beyond

By Aaron Edwards

By Aaron Edwards

Published by Merrion Press, 2023

Reviewer: Kieran Glennon

The titles of recent books examining unionism are instructive, Susan McKay’s brilliant 2021 contribution being a case in point: Northern Protestants On Shifting Ground. Its cover featured an effigy of Lundy, Governor of Derry at the start of the Siege of 1689, providing a subtle reminder that Captain Boycott was not the first man to see his surname become a verb. McKay is from a Protestant unionist background, but writes critically about “her people.”

Aaron Edwards is not a fan of hers, but the title of his new book is equally telling: A People Under Siege. However, Edwards places himself much more firmly inside the tent, with a Prologue that describes a contested Orange march in Greencastle, just north of Belfast, encountering ferocious protests from local residents on the Twelfth of 2001 – he was taking part in the march, as the local Orange Lodge had been his grandfather’s: “I felt like I was among friends. Amongst people like me.”

Having thus nailed his colours to the mast, his introduction gives a brief overview of the political roots underpinning unionism, particularly the Presbyterian tradition of covenanting as practised by the early Scottish planters and given philosophical expression by Enlightenment writers such as Thomas Hobbes and Frances Hutcheson.

In Ireland, the Enlightenment influenced Belfast’s radical Presbyterians to form the United Irishmen but a reaction against it was the formation in 1795 of the Orange Order as a counter-revolutionary . Given that Hutcheson died over fifty years before the Act of Union, it would have been illuminating to see whether and how he influenced the development of late nineteenth-century unionism, but he is quickly left behind – for now.

The book proper begins at the immediate run-up to the creation of Northern Ireland under Government of Ireland Act of 1920. Partition had an extremely violent birth, particularly in Belfast – but here, Edwards makes an appalling factual error.

He references Niall Cunningham’s 2013 article The Social Geography of Violence during the Belfast Troubles 1920-22, which states “It has been possible, according to the records, to assign religions to the victims in just over 95 percent of cases, and of that figure Catholics made up 56 percent while Protestants totalled to 39 percent.”

But in Edwards’ hands – and, more critically, those of whichever editor was asleep at the wheel – this becomes “out of these deaths, 56 per cent were Protestant and 39 per cent Catholic.”

This is more significant than a mere typo, as the disproportionate violence inflicted on Belfast nationalists prompted their adoption of the term “Pogrom.” However, Edwards’ inversion could give the impression that the first day of the Somme was not the only blood sacrifice paid by northern unionists as part of the formation of Northern Ireland.

Other voices

While this error is unforgiveable, it is worth resisting the urge to slam the book shut on page 26, as the next chapter, “The People of Independent Thought,” introduces a fascinating theme that runs throughout the chapters dealing with the decades between the Pogrom and the Troubles.

This is the presence of other voices competing with the Ulster Unionist Party (UUP) for the support of working-class unionists – voices such as Independent Unionist Tommy Henderson and especially socialists like Harry Midgley, Sam Kyle, Jack Beattie and William McMullen.

Midgeley and McMillen had been supporters of James Connolly’s socialist republicanism, while Kyle and Beattie were trade union officials with experience in the class struggle that followed the Great War; the latter three went on to become key figures in the Northern Ireland Labour Party (NILP).

‘Official’ Unionism in Northern Ireland managed to control labour and other discontent within its banner, but other voices in Ulster Protestant community remained.

As the economic downturn of the 1920s ushered in the Great Depression, these voices became more influential, culminating in the Outdoor Relief protests and riots of 1932, in which both Catholics and Protestants demonstrated violently against inadequate welfare provision during the Great . With the cross-class cohesion of unionism once again threatened, as it had previously been by the 1919 Belfast engineering strike, the UUP resorted to an old tactic. Here, I was surprised to learn that, even by the 1930s, the Ulster Unionist Labour Association (UULA) hadn’t gone away, you know.

Originally founded in 1918 by figures with dubious socialist credentials such as Edward Carson and J.M Andrews, director of the Belfast Ropeworks, the UULA’s purpose was to ensure that working-class unionists kept their grievances in-house, thus diverting them from the pull of left-wing ideas, particularly in the aftermath of the Russian Revolution.

Little had changed since then in terms of its objectives, as its 1934 report stated:

“If Socialism and Communism with their wild cat schemes were to gain the upper hand, no section of the community would suffer more than the industrial workers. The interests of Ulster must be safeguarded against those who are striving to destroy the State and include all Ulster in an Irish Republic.”

The Second World War brought little respite for the UUP. Complacency on the part of governments led first by James Craig, then by Andrews, led to chronic under-provision of defences against air-raids – the Belfast Blitz saw Luftwaffe bombs kill 1,100 people and destroy or damage over half of Belfast’s entire housing stock.

Meanwhile, Northern Ireland’s industry made only a haphazard contribution to the war effort and levels of recruitment to the British Army were under-whelming, probably not helped by the fact that the local working class was more inclined to belligerence on its own behalf, with “walkouts rising from 114 in 1940 to 242 in 1941,” while “3 million hours were lost to strike action in the nine months to April 1943.”

Against that backdrop, the next Prime Minister, Basil Brooke, felt compelled to ignore his patrician instincts and support the welfare state reforms introduced by the UK’s post-war Prime Minister, Labour’s Clement Attlee, chief among them the foundation of the National Health Service. But despite such concessions, “the Unionist government’s plans for its working-class supporters amounted to little more than ensuring their energies were responsibly channelled in support of their socio-economic and political ‘betters.’”

Meanwhile, the Northern Ireland Labour Party (NILP) made electoral gains, particularly during the late 1950s as it began reaching out to all parts of the working class, not just Protestants. This resulted in them getting four MPs elected in 1958 and while Edwards is correct to highlight this as a breakthrough – it certainly was for the NILP – he probably oversells its wider significance: there were 52 MPs in Stormont, so four NILP MPs were never going to threaten the hegemony of the UUP’s 37 MPs.

Nevertheless, Edwards writes warmly of the NILP, stating that they “chose to present a more inclusive alternative to maintaining the Union … [they] began to articulate a vision for the future that would better maintain the Union in the long term.” This warmth on his part will become significant again later.

Civil Rights: unionism fractures

One of the NILP’s slogans was “British rights for British citizens” and this, of course, brings us to the emergence of the Civil Rights movement.

Despite occasional rumblings from the working class, the general attachment of unionists to the governing monolith had remained intact since 1921, due to “the constant drip-feed of alarmist speeches by their leaders, who conjured up the IRA bogeyman to keep their followers in a state of perpetual political anxiety.”

However, Civil Rights prompted a deep and long-lasting fracture within unionism, although not along class lines.

Rather, Edwards characterises the dividing line as being between Ulster British, exemplified by the then Prime Minister Terence O’Neill, who favoured liberal, tolerant reforms, and Ulster loyalists, who “… tended to see Northern Protestants as their ‘primary imagined community,” while their ‘secondary identification with Britain involves only conditional loyalty.’ In order to preserve their political union and identity, they saw domination over Catholics as essential.”

The key political figure among the latter tendency was Ian Paisley, who later went on to found the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP). At the same time, “‘certain Unionist politicians’ conspired with others to raise a paramilitary gang” – the new UVF; Edwards sees this as part of a wider conspiracy within unionism to oust O’Neill.

Opposition to loyalists’ sectarian response to Civil Rights demands came from an unexpected quarter in 1967:

“We find there is a growing tendency for people to regard the words ‘civil and religious liberty’ as something which applies only to one section of the community, who feel that for some reason liberty is to be enjoyed only by themselves and that those who may be opposed to their particular ideals must be stopped from expressing their views no matter what the cost.”

Astonishingly, these were the words of the Grand Master of the Orange Order, speaking on the Twelfth that year.

But loyalists’ violent reaction to the Civil Rights campaign and O’Neill’s defeat by the right wing within the UUP led to his resignation in April 1969. Four months later, Derry and Belfast erupted in rioting and the British Army was sent in to restore order. Edwards notes that “most soldiers deployed in the city [Belfast] had quickly come to see the Protestant community as the aggressors.”

O’Neill’s successor as Prime Minster, James Chichester-Clark attempted to ride two horses at once, on the one hand making conciliatory noises about reforms to tackle unemployment and poor housing for the benefit of all, but on the other hand appealing to London for more troops and for them to take firmer action against (Catholic) “troublemakers.”

Unionist unity fractured between hardliners and reformers over the Civil Rights movement of the late 1960s.

By the summer of 1970, the Provisional IRA had emerged as a potent force at the “Battle of St Matthew’s” (a gun battle between them and loyalists in east Belfast) and the British Army’s had managed to alienate many of Belfast’s nationalists by the Falls Curfew, inn which they ransacked that Catholic district of Belfast in search of arms Chichester-Clark failed to secure additional troops and so, in 1971, became the latest reform-inclined Unionist Prime Minister to resign.

His replacement, Brian Faulkner, tried to placate opponents of Unionist rule by including in his cabinet a former NILP MP, David Bleakley – but Bleakley only lasted until August 1971, resigning when “An accelerant poured on the open fire of disorder on the streets was the decision by the Unionist government to impose the policy of internment.” Despite the disastrous impact of internment, Faulkner refused to hand responsibility for security back to London, leading to the abolition of the Stormont Parliament in March 1972 and its replacement by direct rule.

This sparked fury among loyalists. Thousands of loyalist paramilitaries paraded openly; former Minister for Home Affairs Bill Craig founded Ulster Vanguard, which organised “mass fascistic rallies presided over by Paisley and Craig, in which the latter arrived in “‘an ancient limousine, complete with motorcycle .’”

A Northern Ireland Assembly was elected in June 1973, followed by the establishment of a power-sharing Executive with Faulkner as chief minister and with nationalists such as Gerry Fitt and Paddy Devlin as ministers. Crucially, the Executive was accompanied by the Sunningdale Agreement, which aimed to establish a Council of Ireland giving Dublin a consultative role in Northern Ireland.

Faulkner became the latest Unionist leader to be deposed for supposed appeasement of nationalism.

The Ulster Workers’ Council, an outshoot of the Loyalist Association of Workers, “a group based around the state’s heavy industry, with close connections to loyalist paramilitary organisations,” instituted a general strike in mid-May 1974, with the explicit intention of bringing down the Sunningdale Agreement.

Two-thirds of all electricity output was shut down, the UDA blocked the port of Larne and the UVF planted bombs in Dublin and Monaghan. The strike succeeded, Faulkner and the rest of the Executive resigned and direct rule resumed at the end of the month.

Edwards notes that this “very loyalist coup” also marked the final eclipsing of the NILP, “the one pro-Union party with the genuine concerns of working-class unionists at its heart.” At a wider level, Paisley was by now the clear leader within loyalism.

Peace process

However, he was not yet the leader of unionism in general, so opposition to the 1985 Anglo-Irish Agreement was led by both him and the latest leader of the UUP, Jim Molyneaux. This included a rally of 100,000 at Belfast City Hall.

The Agreement was significant, not just because of the consultative role it gave the Irish government in Northern Ireland, but because it highlighted the growing distance between northern unionists and their erstwhile allies in the British Conservative Party – it was signed by Margaret Thatcher.

Given the ongoing IRA violence, particularly in border areas, Edwards notes “a general feeling of insecurity began to percolate through the broader unionist community. Some militant elements undoubtedly acted on this, with loyalist paramilitaries embarking on a renewed terror offensive against Catholic civilians and republican activists.”

Many unionist feared the 1990s peace process as a ‘sell out’.

Unionist insecurity was increased by the Downing Street Declaration of 1993, in which the British government stated that it had “no selfish or strategic interest” in Northern Ireland and that it was up to the people of the island, north and south, to decide on the basis of consent whether they wanted a united Ireland. It also re-iterated the legitimate interest of the Irish government in Northern Ireland issues – the British government now appeared to be positioning itself as a neutral referee acting in concert with Dublin where possible. Paisley denounced the Declaration as a sell-out, but Molyneaux did not, for which Paisley denounced him as a traitor.

The next major landmark in the developing peace process was the IRA ceasefire of August 1994 which was followed six weeks later by a similar announcement from the loyalist paramilitaries, the UVF and the UDA. Their ceasefire opened the way for their respective political wings, the Progressive Unionist Party (PUP) and Ulster Democratic Party (UDP) to become involved in the peace talks.

The peace process was not universally welcomed within unionism. Billy Wright broke away from the UVF to set up the Loyalist Volunteer Force, which orchestrated protests around contested Orange marches at Drumcree outside Portadown; when those Orange marchers were eventually forced down the nationalist Garvaghy Road, they were joined by Paisley and David Trimble, Molyneaux’s successor.

However, Trimble, along with the leaders of the PUP and UDP, both governments, Sinn Féin and the SDLP – but, significantly, not Paisley – were signatories to the Good Friday Agreement (GFA) in April 1998. This was the culmination of the peace process, providing for a power-sharing Assembly and Executive, North-South and East-West ministerial bodies and the dropping of the irredentist claims in Articles 2 and 3 from the Irish Constitution.

Unionism was divided in response to the GFA. According to Edwards, “The DUP’s brand of anti-Agreement unionism built on its thirty-year track record of oppositional politics, where dangers abounded for unionists and only a strong, united political leadership could offer an alternative.”

Although a referendum on the GFA was passed by 71% of the total electorate, when elections to the new Assembly were held, anti-Agreement parties won enough votes to suggest that unionism was actually split down the middle. Over time, pro-GFA unionists gradually lost support and leading UUP figures like Arlene Foster and Jeffrey Donaldson defected to the DUP, although Edwards says “this owes more to the ineptitude of the UUP than to the strategic articulateness of the DUP.”

April 2007 saw “a Damascene conversion few ever expected to witness” – Paisley became First Minister of the Executive alongside Sinn Féin. However, that move prompted yet another unionist split, this time within the DUP, as Jim Allister left to set up the Traditional Unionist Voice (TUV).

The GFA had been extolled for the “peace dividend” it would provide for all in Northern Ireland, but working-class loyalists felt this did not materialise for them. Their communities remained blighted by poverty, unemployment and poor educational attainment; Edwards points out that deprivation was actually worse in Catholic areas, but “it was the construction of a victim identity by some loyalists themselves that was ultimately feeding these feelings of insecurity.”

Apart from economic issues, Drumcree had been “perceived to be a loss of their tribal rites” and this impression that their former status was being eroded by concessions to republicans was compounded by the decision of Belfast City Council in 2012 to limit the flying of the Union Jack over City Hall to a few days a year.

The “flag protests” that followed effectively sounded the death-knell for the PUP (although it still exists on paper); according to Edwards, it “always had two wings: one Ulster British, with some semblance of democratic socialism, and the other Ulster loyalist.”

Given the potential alternative it offered, he laments its demise, pointing out that it had tried to channel the anger of the protests in more political directions and in doing so, actually succeeded in expanding its ranks. However, in an absolutely inspired metaphor, he says “The influx of new members in the wake of the flag protests included loyalists more in tune with ‘The Sash’ than ‘The Internationale.’”

Edwards takes an extended look at the development and downfall of the PUP – it would have been interesting to see a similar analysis of its counterpart, the UDP. Crucially, the two paramilitary organisations out of which those parties grew, the UVF and UDA, remain in existence.

Brexit

In his final speech to the European Parliament, Paisley called the EU a “Tower of Babel” – perhaps it is unsurprising that in seeking a withering description, a fundamentalist preacher would turn to the Bible for inspiration.

Edwards argues that the DUP’s support for Brexit drew from its particular ideas on sovereignty and democracy, rooted in a very Protestant interpretation of British identity – but he does not explain in depth how this works in practice, other than stating that they see European integration as yet another existential threat to Northern Ireland’s place in the Union.

The DUP’s support for Brexit has ironically destabilised the Union which they wish to preserve in perpetuity.

He does highlight a paradox – that the Brexit advocated by a Conservative government was voted for by people badly affected by the austerity policies of successive Conservative governments. He suggests that the explanation for this apparent contradiction lies not in economics but in the shifting definitions of identity within Northern Ireland – British, Irish, Northern Irish and growing numbers of immigrants who are arguably none of the above.

Thankfully, Edwards does not retrace the painful genesis of the Brexit Withdrawal Agreement and its accompanying Northern Ireland Protocol or the protracted debates around hard borders, soft borders, customs unions and backstops, other than to highlight the fears of extreme loyalists such as Jamie Bryson that the EU and Irish government would be given more influence over the Northern Ireland economy than the British government. Bryson and the TUV argue that, just as the Good Friday Agreement ultimately aimed at creating a united Ireland by political means, the Protocol has the same stealthy objective but uses economic means.

The fact that the Withdrawal Agreement and Protocol were negotiated by the British government and approved by the UK Parliament is, it appears, irrelevant to anti-Protocol loyalists, other than to further stoke their fears of being sold out.

The future

In his closing chapter, Edwards returns to the philosopher Francis Hutcheson, an early advocate of utilitarianism – the idea of “extending goodwill in a benevolent and altruistic way to the greatest number of people possible.” He says that “Unionists in Northern Ireland have for too long been distracted from fulfilling the potential of their political philosophy to make the world a better place for everyone, regardless of their social class, ethnic, national, religious, cultural or other sectional identities or .”

This is a noble sentiment, and perhaps explains the way that left-leaning but pro-Union voices like the NILP and PUP are given an elevated prominence in the book, way beyond what their actual impact on events would merit.

Edwards contrasts what he sees as constructive and inclusive ‘British unionism’ with identity-based ‘Ulster unionism’.

However, it sits at odds with unionists’ track record – Edwards has the good grace to acknowledge that they “…hardly covered themselves in glory under the old Stormont majoritarian regime that did everything it could to deny those deemed disloyal the full British rights they were owed.” He argues that unionists should instead try to build an inclusive Union for the joint benefit of all four parts of the UK, insisting that this is the only way to maintain the Union.

The critical flaw with this approach is that its advocates have vanishingly few tangible benefits of belonging to a post-Brexit UK that they can actually point to. To cite one current example, Lough Neagh being as polluted as sewage-encrusted beaches in England may well represent parity, but hardly parity of esteem.

In addition, Edwards’ approach requires an implausible abandoning of identity politics within Northern Ireland. The only noticeable shift from previously-held identity positions has been the growth of the “Other” political designation – Alliance and the Green Party – in successive post-Brexit elections in Northern Ireland, which suggests that the self-identification of many previous unionist voters is weakening.

But demographic changes have only encouraged northern nationalists to view the attainment of the key goal of their identity politics as drawing closer, thus deepening the appeal of such politics to them.

Meanwhile, anti-Protocol loyalists, ranging from the DUP to the TUV to Bryson, have continuously dialled up the perceived threats to their British identity and emphasised how staunchly they remain attached to the symbols of that identity. However, in another wonderful turn of phrase, Edwards says that “Moderate unionists find the kind of ‘flag-shagging’ displayed by Ulster loyalists to be a tribal-based relic of a bygone era.”

Summary and conclusion

Edwards has set out to present a history of unionism – not of Northern Ireland in general – from partition to the contemporary situation. A century is a lot to cover, so it is perhaps understandable that the book progresses in staccato fashion, skipping forward several years at a time; this jumpy flow is not helped by occasional detours examining the local impact of wider events on Edwards’ native Rathcoole estate in north Belfast.

The book’s greatest achievement is how it illustrates that unionism is not, and perhaps never was, as monolithic as some might imagine.

The book’s greatest achievement is how it illustrates that unionism is not, and perhaps never was, as monolithic as some might imagine.

While events like the Outdoor Relief riots are reasonably well-known, Edwards’ portrayal of the existence of a separate class-conscious strand among working-class unionists, particularly in the first three decades after partition, is refreshing. This current of thinking, although almost subterranean, represented a potential source of division, which the old UUP leadership succeeded in averting.

However, that leadership was powerless to prevent the rupture within unionism which Civil Rights brought about. In 1968, Terence O’Neill said “Ulster stands at a crossroads” – unionism chose the wrong road. A succession of Prime Ministers who entertained notions of reform that would allow non-unionists to participate in Northern Ireland as equals were jettisoned and loyalism, in the form of the DUP and paramilitaries, emerged as a powerful alternative to the old UUP – but along the way, the Stormont citadel that had remained in place for fifty years was lost. Edwards does a fine job of charting these developments.

One of the book’s weaknesses is its title – A People Under Siege is a misnomer. Siege implies an external threat but also offers the prospect of external relief. But since the imposition of direct rule, the corner in which unionism – and especially loyalism – finds itself is one it has painted itself into, after decades of mounting paranoia that its one-time supporters in London offered not relief, but betrayal.

However, the Anglo-Irish Agreement, Downing Street Declaration and Good Friday Agreement were steps on the road to peace, not the road to perdition as Paisley argued. He and other loyalists might have done well to remember that the Government of Ireland Act that originally gifted them a Northern Ireland Parliament also contained provisions for a Council of Ireland. Perhaps the British never actually changed their tune?

Edwards’ proposed route for unionism to take to escape its present impasse is novel, but remains unconvincing, not least because of its utopian pre-conditions. Northern Ireland was founded on the basis of preferential treatment for one polarised identity over the other; in a still-divided society, expecting either Ulster loyalists or northern nationalists to relinquish their respective identities in favour of Ulster Britishness seems completely unrealistic.

This book is an invaluable aid to anyone trying to understand unionism – Edwards has provided a good, layered portrayal of its past since partition and its present conundrums. But whether it has a future is doubtful.