Henrietta Street: From Townhouse to Tenement

By Timothy Murtagh

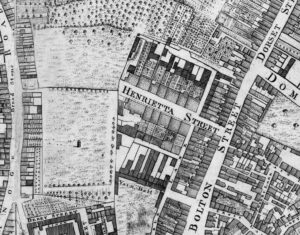

Henrietta Street has many claims to fame. Some historians have pointed to it as one of the earliest examples of ‘Georgian’ street planning in the city, with its elaborately constructed interiors rivalling any of Ireland’s great mansions of that era.

However, there is more to Henrietta Street that its Georgian heyday, as the subsequent two centuries saw it become a symbol for Dublin’s nineteenth-century economic decline, as well its infamous housing problems.

Henrietta Street went from desirable Georgian address to 19th century tenement, illustrating Dublin’s 19th century decline.

By 1900, it had become synonymous with the city’s tenements, with several houses on the street containing as many as a hundred people under a single roof. While it was far from the only tenement ‘district’ in the city, what shocked observers was the contrast between the street’s fortunes in the early twentieth century, and its origins in the eighteenth.

An enclave for the elite

When Henrietta Street had been first built in the decades between 1720 and 1750, it had been designed as an enclave for the elite few- the wealthy and powerful of Dublin. In the decades after 1740, some of the most influential politicians and landowners had their residence on the street: men like the Earl of Shannon, or Luke Gardiner (the man responsible for building much of Dublin city’s north side). In the eighteenth century, it was said that the real business of Irish politics wasn’t done in the Irish parliament buildings, but instead in the drawing rooms of Henrietta Street.

After 1800, that all began to change. First of all, the Irish parliament no longer existed, thanks to an Act of Union which subsumed Ireland into the newly forged United Kingdom. From now on, decisions regarding Ireland would be taken in a union parliament in London, not in Dublin.

As a result, many Irish aristocrats and politicians found that there was no longer any point in maintaining a Dublin townhouse- London was where power was now based. As a result, there was an exodus of wealthy homeowners out of Dublin, leading to a slump in the market for the upper-class homes they had once lived in.

This was combined with a larger economic decline of the city as a whole, as key manufacturing sectors lost out to rapidly industrializing towns like Manchester and Sheffield. While not every economic problem the city experienced could be blamed on the Union, it certainly marked the point at which the city’s fortunes began to change for the worse.

In the early 19th century Henrietta Street became a hub for the legal profession.

This did not, however, mean that the city’s many fine Georgian townhouses lay empty. Instead these buildings were converted, with many fine mansions transformed into hotels, clubs and offices. After 1820, many of the houses in Henrietta Street were converted into lawyer’s office. One thing in the street’s favour was its proximity to the King’s Inns, the organisation that regulated the Irish legal profession.

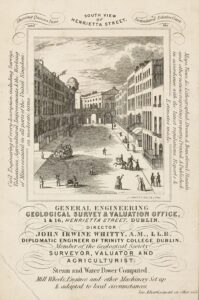

With its impressive new buildings at the top of Henrietta Street completed by 1817, the King’s Inns brought a wave of lawyers to the area, many taking offices on the street. By the 1830s, nearly every other building on the street contained either attorneys, barristers or judges, as well as housing the King’s Inns library. The street was even described as having ‘the air of a legal university’. The street’s status as a ‘professional address’ also attracted the offices of agencies like the General Geological Survey and Valuation Office.

After 1850, Henrietta Street was to play host to a very important legal institution: the Encumbered Estates Court, which was located in number 14.

This court specialised in disputes concerning the estates of over-indebted landlords (of which there were many in the nineteenth century). As such, number 14 was divided into the offices of the three ‘commissioners’ of the court, while a court room was constructed at the rear of the building, in what had once been the coach house at the end of the garden.

By all accounts the court was busy, which one barrister commenting that ‘the quantity of work which flowed in upon the court, especially in the years 1851–4 was in excess of all anticipations’.

Perhaps because of how busy the court could get, it was decided to relocated it in 1860, leaving Henrietta Street. While some of the lawyers would remain for several decades, the years after 1860 saw many of the ‘professional’ class begin to desert the street.

The 1860s and 1870s were a period during which much of the surrounding neighbourhood was beginning to noticeably decline, with tenements spreading across the north-side of the city, in what had once been the Gardiner estate.

What was occurring around Henrietta Street was also taking place in addresses like Summerhill and Mountjoy Square The first tenements to appear in Henrietta Street were first listed in 1867, and by the end of the century nearly every house on the street was being let out in this manner.

Tenement

Initially, the tenements in Henrietta Street were not ‘the worst of the worst’. For example, number 14 (the site of the current tenement museum) was first let out as apartments by Thomas Vance, one of Dublin’s wealthiest businessmen and builders. It seems that when he purchased the house, Vance had hoped to turn it into a ‘model’ tenement: he installed toilets and clean running water on each landing of the building. In a city where most tenements had only a shared tap and toilet in the backyard, the conditions Vance was offering were better than most.

The 1860s and 1870s were a period during which much of the surrounding neighbourhood was beginning to noticeably decline, with tenements spreading across the north-side of the city

This was reflected in higher than average rents for tenement rooms. Several adverts from the 1880s confirm that 3 shillings a week was the minimum one would pay for a single room, with the rent for a three-room apartment in Henrietta Street going as high as 6 shillings by 1900. This was roughly the same as was being charged in buildings run by groups like the Iveagh Trust or the Dublin Artisans Dwellings Company, bodies that were criticized for mainly catering to skilled and better-paid workers. In number 14 there is evidence that, at least initially, the rooms there attracted those better off than the average worker.

For example, in 1881, one of the building’s tenants advertised that they were selling their piano, and that they were willing to take £14 10s for it. While anecdotal, it indicates that during the 1880s, at least, Henrietta Street was not yet catering to the truly destitute labourers who composed so much of the city’s population.

As time went by, however, things began to change. During the 1890s and 1900s, conditions in the street noticeably deteriorated, partly due to ‘middlemen’: speculators who took a lease on a tenement or part of a tenement, then sub-divided its apartments and inflated the rent.

As a result, even ‘good’ tenements tended to get run down overtime, frequently becoming over crowded. Nowhere was this more apparent than Henrietta Street. By 1911, there were nearly a thousand people in Henrietta Street, across nineteen buildings. In number 14 alone there were a hundred tenants living under a single roof.

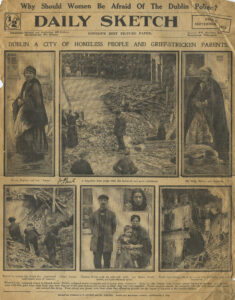

Overcrowding and poverty

Life in most Dublin tenements was bleak. With most tenants living on extremely tight budgets, there was little money for furnishings or even proper bedding, while overcrowding meant little privacy, with large rooms divided with thin partitions. Meanwhile physical deterioration meant broken windows, patched rooves, uneven floorboards and (worst of all) extremely unsanitary toilets.

In 1906, a journalist for the Irish Times described how in the city’s tenements ‘the chimneys nearly all smoke, and there is not a sound window in the whole building. The floors are all hills and hollows; form some of the rooms you can look straight down through the holes and see what is doing in the room underneath; here and there they are patched up with pieces form an old soap box, or they may be only covered with a sack’.

However, for many Dubliners a room in such a tenement was all they could afford. The nineteenth century had seen the decline of many of Dublin’s traditional manufacturing industries, leaving few steady or good-paying jobs. In 1911, a quarter of the city’s adult males were employed as unskilled ‘general labour’, such as the carrying trade and casual labour on the docks.

This meant that the workforce was extremely vulnerable to victimization by employers, low wages, long hours and periodic unemployment. The city economy’s reliance on transport and distribution, as well as the dominant industries of brewing and distilling, meant a high proportion of workers were casual, often discharged in slack times.

Periodic unemployment was often built into many occupations with seasonal periods of slack work, being a feature of tailoring, dressmaking and the building trades.

By 1900 the once grand houses on Henrietta Street contained some of Dublin’s worst slums.

One result of the bad housing conditions was that disease and infection ran rampant. While individual families attempted to keep their own rooms clean, the cramped nature of tenement living meant that disease could quickly spread within and between families. Tuberculosis, typhoid, scarlet fever, measles, cholera, and diphtheria: all were major killers of Dublin’s poor, especially the young. Few tenement families had their own in-house water supply, instead relying on a single outside common tap, as well as still having to carry and store water in infected surroundings, making washing and hygiene problematic.

Moreover, despite the growing number of flush toilets, Dublin’s main drainage scheme was not completed until 1906; until then the city’s sewage simply flowed into the river Liffey, gaining it a reputation as an ‘Irish river Styx’. The city’s death rate remained high, as serious epidemics could still occur, such as the spate of measles infections in 1899, while an outbreak of smallpox in 1903 killed thirty-three Dubliners.

While the numbers dying from typhoid, typhus and cholera were declining, instances of the ‘wasting disease’ of tuberculosis only peaked in 1904 in Dublin, accounting for 13,000 deaths that year. Children were particularly vulnerable. Dublin had the highest infant mortality rate in the British Isles for every year between 1899 and 1913.

Looking at Henrietta Street, the 1911 census reveals that the majority of families there had lost at least one child, with some heart-breaking cases of loss. For instance, in No. 8, the forty-one-year-old Mary O’Neill had given birth to fourteen children in her life, only one of whom had survived, an eleven-year-old daughter named Sarah.

It was not just the threat of disease that made tenement life so dangerous, but the physical threat posed by the buildings themselves. Decades of overcrowding and neglect had undermined the structural integrity of many buildings, with many only being kept upright thanks to external supports and struts. There were several cases of tenements collapsing in 1902, 1909 and 1911, each time causing fatalities. However, it was a tenement collapse in 1913, just around the corner from Henrietta Street, that marked a turning point. The collapse of two buildings in Church Street in September of that year killed seven people, including two small children.

The official report of 1913 showed that more than 20,000 families lived in one-room tenement accommodation, with a shocking number of these buildings classified as ‘unfit for human habitation’. I

The public outrage sparked an official inquiry into the conditions of Dublin’s tenements. The official report that resulted revealed some appalling facts: more than 20,000 families lived in one-room tenement accommodation, with a shocking number of these buildings classified as ‘unfit for human habitation’. In addition to sparking outrage, the report called for the construction of 14,000 new houses, to be built by the city government.

This programme of house building would cost ten times what the city had spent on public housing over the previous thirty years. Yet this dramatic suggestion would not soon be realised. Within six months of this housing report, the First World War erupted, soon followed by the outbreak of the 1916 Easter Rebellion and an ensuing War of Independence in 1919-21.

These dramatic events effectively derailed plans for sweeping housing reform, with only a handful of public housing schemes completed in these years. It would not be until the 1920s and 1930s that large-scale construction of affordable housing began in the suburbs, while several of the houses in Henrietta Street continued to be used as tenements up until the end of the 1970s. There would be no quick or easy solution to the problems of Dublin’s tenements.

These dramatic events effectively derailed plans for sweeping housing reform, with only a handful of public housing schemes completed in these years. It would not be until the 1920s and 1930s that large-scale construction of affordable housing began in the suburbs, while several of the houses in Henrietta Street continued to be used as tenements up until the end of the 1970s. There would be no quick or easy solution to the problems of Dublin’s tenements.

Timothy Murtagh is the author of the recently published book, Spectral Mansions: The making of a Dublin Tenement, 1800-1914 (Four Courts Press, €30.00). Available now in all good bookshops and online via www.fourcourtspress.ie