An Ongoing Injustice: State Responses to ‘Historical’ Abuses in Ireland

By Maeve O’Rourke

By Maeve O’Rourke

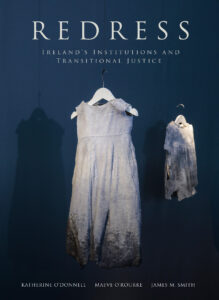

This is an adapted extract from an essay by Maeve O’Rourke in the recently published book REDRESS: Ireland’s Institutions and Transitional Justice (UCD Press 2022), edited by Katherine O’Donnell, Maeve O’Rourke and James M Smith.

In her essay entitled ‘State Responses to Historical Abuses in Ireland: “Vulnerability” and the Denial of Rights’, O’Rourke argues that the Irish State has furthered injustice in the ways that it has purported to investigate and account for numerous forms of so-called ‘historical’ gender-based abuse. O’Rourke argues that the Irish State has refused to treat survivors of Magdalene Laundries, Mother and Baby Homes and forced family separation as equal citizens deserving of all forms of justice that the democratic State has to offer. Instead, she claims, survivors have been characterised as ‘vulnerable’ and in need of specialised justice mechanisms. These specialised processes have cut survivors off from ordinarily available avenues of access to information, civil and criminal justice, inquest proceedings and truth-telling. The specialised mechanisms have not placed human rights or Constitutional law at their centre, and State representatives persist in denying the gravity and pervasiveness of the human rights and Constitutional rights violations suffered—some of which continue to this day.

The following extract describes how, in O’Rourke’s view, the Irish State continues to minimise and deny the nature and extent of the abuses suffered, and how it has denied survivors access to ordinary democratic justice and accountability procedures.

The numbers in brackets throughout the text refer to sources which are noted at the end of the extract.

Maeve O’Rourke is an Assistant Professor of Human Rights at the Irish Centre for Human Rights, School of Law, National University of Ireland Galway.

A State of Denial

To this day, the Irish state refuses to accept that it is responsible for constitutional or other human rights violations in Magdalene Laundries, despite the Taoiseach (Irish Prime Minister) issuing an official apology to survivors in 2013 and the President of Ireland and Minister for Justice adding their own public apologies since. (1) (2) (3)

It is documented extensively that Magdalene Laundries incarcerated, denigrated, and forced into unpaid labour – often for years, decades and whole lifetimes – well over 10,000 girls and women from the foundation of the Irish Free State in 1922 until the last institution’s closure in 1996; that state agents placed over one quarter of those girls and women in the Catholic Church-run institutions; and that the state not only failed to regulate the institutions but actively supported them by contracting with the nuns for vast laundry services, ensuring under the Conditions of Employment Act 1936 that the nuns were not required to pay wages, and providing the assistance of An Garda Síochána (Irish police force) in returning escapees. (4)

Well over 10,000 girls and women were incarcerated in Magdalene Laundries from the foundation of the Irish Free State in 1922 until the last institution’s closure in 1996; and 56,000 and 57,000 children in 18 Mother and Baby Homes and County Homes between 1922 and 1998

Yet, the government insists that there is ‘no factual evidence to support allegations of systematic torture or ill treatment of a criminal nature in these institutions.’ (5)

It contends, further, that the available evidence does ‘not support the allegations that women were systematically detained unlawfully in these institutions or kept for long periods against their will.’ (6)

A state report in 2015 to the United Nations (UN) Committee against Torture (CAT) asserted: ‘No Government Department was involved in the running of a Magdalen Laundry. These were private institutions under the sole ownership and control of the religious congregations concerned and had no special statutory recognition or status.’ (7)

The Irish state’s July 2020 Defence to Elizabeth Coppin’s ongoing individual complaint to the CAT goes so far as to claim that her detention as a teenage girl in three Magdalene Laundries was not ‘by reason of her gender’ and therefore was not discriminatory. (8)

For the past 11 years the government has repeatedly rejected recommendations from the Irish Human Rights and Equality Commission (IHREC) and five UN human rights bodies to establish an independent and thorough investigation into the allegations of widespread, grave and systematic human rights abuses in Magdalene Laundries. (9) (10)

Similarly, the Irish state refuses to accept that grave constitutional and human rights violations are disclosed or even indicated by the extensive publicly available evidence of systematic arbitrary detention of girls and women and neglect of their children in state-funded Mother and Baby Homes and County Homes, and the widespread coerced or otherwise unlawful adoption of children born to unmarried mothers until the latter part of the twentieth century. (11) (12)

Numerous UN human rights bodies have recommended an independent, thorough and effective investigation into all allegations of human rights violations in the family separation system that is estimated to have involved at least 182 agencies, individuals and institutions from independence onwards. (13) (14)

The government has declined to establish any independent investigation into historical adoption practices generally, within and from Ireland. State bodies continue to use the phrase ‘incorrect registrations’ to describe the systematic illegal registration of ‘adoptive’ parents on a child’s birth certificate, employed as a method of circumventing adoption laws and effecting de facto adoptions in the absence of legislation permitting domestic adoptions before 1953 and foreign adoptions generally. (15) (16)

To this day, the Irish state refuses to accept that it is responsible for constitutional or other human rights violations in Magdalene Laundries

Ó Fátharta has reported that staff in the national Child and Family Agency (Tusla) were instructed in 2017 not to refer to records of a 16-year-old mother being forced in 1974 to sign a false name on an adoption consent form as indicating an ‘illegal adoption’ because ‘stuff is FOI’able… and it could be used against us if someone takes a case.’ (17)

The final report of the statutory Mother and Baby Homes Commission of Investigation (MBHCOI), published in January 2021, addressed the treatment of 56,000 mothers aged as young as 12 and an additional 57,000 children in 18 Mother and Baby Homes and County Homes between 1922 and 1998. Testimony provided by women to the MBHCOI described, among other abuses:

- detention without legal basis (‘we were locked in and there was absolutely no way of getting out.’ … ‘I attempted to run away twice with two other girls, but they always found us and brought us back’), (18) (19)

- forcible repatriation from England, (20)

- additional coercion to relinquish a child (‘I told him I didn’t want to sign but he just told me to shut up.’ …‘I was under continued pressure from the social worker to sign the adoption consent form’) (21) (22) and

- child stealing (‘when my baby boy was six-seven weeks old, he was wrenched from my breast by one of the nuns whilst I was breastfeeding him and taken away for adoption’). (23)

Women reported:

- denial of contact with relatives, (24)

- extreme neglect (‘[my son was] in a closed off area called the dying room. I begged the nuns to take my son to a hospital, but they only did so after two weeks had passed. …I do not even know whether he was buried in a coffin.’ (25) …‘As the pain progressed, I was locked in what I can only describe as a cell. …I was left there all night with no attention’) (26) and

- subjection to forced unpaid labour (‘[It was] heavy work scrubbing clothes and bedding on boards, washing and ironing all with our bare hands during a six-day week.’ … ‘We were made to work even if we were very ill, as I was. No excuses were ever accepted’). (27) (28)

The survivor testimony and archival material which the MBHCOI summarised in its final report is further reflective and corroborative of the above excerpts. (29)

Nonetheless the MBHCOI concluded that:

- ‘There is no evidence that women were forced to enter mother and baby homes by the church or State authorities’; (30)

- The girls and women in the institutions ‘were not “incarcerated” in the strict meaning of the word but, in the earlier years at least, with some justification, they thought they were’; (31)

- The girls and women ‘were expected to work but this was generally work which they would have had to do if they were living at home’; (32)

- There is ‘very little evidence that children were forcibly taken from their mothers… the mothers did not have much choice but that is not the same as “forced” adoption’; (33)

- Regarding vaccine trials conducted by the Wellcome Foundation and Glaxo Laboratories between 1934 and 1973: ‘It is clear that there was not compliance with the relevant regulatory and ethical standards of the time as consent was not obtained from either the mothers of the children or their guardians and the necessary licenses were not in place. There is no evidence of injury to the children involved as a result of the vaccines’; (34) and

- In respect of the thousands of unknown graves of children who died: ‘In cases where the mothers were in the homes when the child died, it is possible that they knew the burial arrangements or would have been told if they asked. It is arguable that no other family member is entitled to that information.’ (35)

The MBHCOI’s final report includes a chapter described as a ‘compilation’ of the testimony which 550 institutional survivors and adopted people gave to its ‘Confidential Committee.’ (36)

Without identifying the extracts to which it refers, the chapter begins with the blanket accusatory statement that: ‘The Commission has no doubt that the witnesses recounted their experiences as honestly as possible. However the Commission does have concerns about the contamination of some evidence. …This contamination probably occurred because of meetings with other residents and inaccurate media coverage.’ (37)

Exclusion from Democratic Accountability Mechanisms

Ireland’s established mechanisms of democratic accountability and rule of law – its civil and criminal justice procedures, its coroners’ inquest system and its information transparency mechanisms such as Freedom of Information, the National Archives and data protection laws – have been kept out of the reach of those affected by the above-mentioned, frequently termed ‘historical,’ abuses.

Prompted by survivor- and adopted-person-led advocacy, the CAT has recommended that the Irish state ensure that civil actions ‘can continue to be brought “in the interests of justice”,’ that the state ‘promote greater access of victims and their representatives to relevant information concerning the Magdalene Laundries held in private and public archives,’ and that ‘information concerning abuses in [Mother and Baby Homes and related institutions] are made accessible to the public to the greatest extent possible.’ (38)

The CAT and other UN human rights treaty bodies have also repeatedly recommended the prosecution of perpetrators where appropriate and access to redress including as full rehabilitation as possible. (39)

An Garda Síochána has never announced that it is investigating the Magdalene Laundries nor does it intend to investigate the deaths of infants at the Mother and Baby Homes.

An Garda Síochána has never announced that it is investigating the Magdalene Laundries nor asked for witnesses to come forward, notwithstanding the available evidence of systematic abuse and the fact that several survivors have made police complaints. (40)

The government claims that ‘[i]t is open to anyone who believes a criminal act took place to make a criminal complaint and it will be investigated,’ while simultaneously asserting that all of the testimony and archival records available to it (which are mostly closed to survivors and the public) demonstrate the ‘absence of any credible evidence of systematic torture or criminal abuse being committed in the Magdalene Laundries.’(41) (42)

With the exception of one minor prosecution of a midwife in 1965 following which she continued to operate an adoption agency for over a decade, neither the adoption system nor the institutions that incarcerated unmarried mothers have been subject to criminal prosecution. (43)

In recent years individuals have complained and various state bodies have delivered reports to the Gardaí regarding:

- non-consensual vaccine trials in Mother and Baby Homes, (44)

- illegal adoptions, (45)

- the burial of thousands of babies’ bodies, unmarked and unidentified, by nuns operating Mother and Baby Homes,(46) and

- the absence of death certificates for all children recorded by the nuns as dying in the institutions.(47)

The Garda Commissioner announced in April 2021 that he does not plan to commence an investigation into the matters summarised in the 2,865-page MBHCOI’s final report because the MBHCOI’s anonymisation of its findings means that ‘there is insufficient detail in the report to commence an investigation.’ (48)

The Garda Commissioner urged survivors of Mother and Baby Homes to come forward with their testimony while cautioning that ‘there will be limitations as to the action we can take in some cases due to matters such as the loss of evidence over time or suspects and witnesses being deceased.’ (49)

He did not mention that his police force is statutorily barred from accessing the entire archive of records gathered by the MBHCOI, pursuant to the inquiry’s underpinning legislation. (50)

Meanwhile, in evidence to a parliamentary committee in early 2021, one survivor explained that when she approached the Gardaí regarding her missing brother who is recorded by the nuns as dying but regarding whom there is no death certificate or burial record, ‘I was blocked and told by the Garda that it was dealing with the commission.’ (51)

Another survivor argued: ‘more than 850 burials in Bessborough [Mother and Baby Home] are unaccounted for and we regard those babies as illegally missing. Accordingly, a full Garda investigation should be initiated, and it should include Garda access to the archives of the religious order and investigate all living personnel, no matter what age.’ (52)

The civil courts are generally unavailable to survivors, and not only because of the secrecy of information (discussed further below). The Statute of Limitations presents an almost total bar to litigation of so-called ‘historical’ claims against either state or non-state actors. (53)

There is no legislative provision for the exercise of judicial discretion to extend in the interests of justice the short limitation period for an action claiming personal injuries in tort, and the few existing exceptions to the limitation period are extremely narrow. (54)

Strikingly, the publicly known nature of the Magdalene Laundries, Mother and Baby Homes and forced adoption abuses was recently found by the Irish High Court, Court of Appeal and Supreme Court to prevent the operation of the ‘concealed fraud’ exception to the ordinary limitation period for personal injury claims. (55)

The O’Keeffe v. Ireland case, concerning the state’s failure to protect an eight-year-old child from sexual abuse at primary school in the 1970s, demonstrates the state’s practice of pursuing litigants for its costs of defending even test human rights cases. Although ultimately successful before the European Court of Human Rights in 2014, when Ms O’Keeffe lost her case at first instance the High Court awarded the state approximately €500,000 in legal costs, to be paid by the plaintiff. (56) (57)

Colin Smith and April Duff note that ‘religious orders and State agencies are vigorous in seeking costs against litigants whose claims against them have failed… [and] victims of historic institutional abuse receiving legal advice will receive a stark warning from their lawyers that if their proceedings fail, they will face financial ruin.’ (58)

Further procedural obstacles to accessing the civil courts identified by Smith and Duff include: a narrow conception of vicarious liability in Irish tort law such that abuse in privately managed, state-funded social care services will not necessarily give rise to state responsibility; the difficulty of determining which defendant(s) to sue, particularly given that religious congregations in Ireland have no independent legal personality; the lack of class action legislation; and the inordinate delays that defendants can cause to the progress of proceedings due to the absence of modern judicial case management procedures in the Irish High Court. (59)

In addition, in order to receive modest payments from an ex gratia ‘restorative justice’ administrative scheme established in 2013, Magdalene Laundry survivors were required by the government to waive all legal rights against the state regarding their abuse. (60)

The MBHCOI’s final report indicates that no more than a handful of coroners’ inquests have been held into deaths in Mother and Baby institutions, despite the fact that 200 mothers and 9,000 (approximately 15 per cent) of children born in the institutions investigated by the MBHCOIdied there and no burial records have been produced for most. (61) (62) (63)

Irish legislation throughout the twentieth century mandated an inquest where a death appeared unexplained or unnatural; current legislation additionally requires a coroner’s inquest in every instance where a person has died while in state custody or detention and permits the Attorney General to direct the holding of an inquest wherever it is deemed ‘advisable.’ Several local coroners have been notified of the existence of mass unmarked graves at sites of former Mother and Baby institutions, including in Tuam where ‘significant quantities of human remains’ were located in a disused sewage tank in 2017 and where they lie still, unidentified. (64) (65) (66) (67)

Basic information, both about one’s personal circumstances and about the systems within which individuals were abused, is withheld in numerous other ways.

The National Archives Act 1986 does not designate health or social care agencies as sources of records that must be preserved and deposited for public access. (68)

The list of state bodies to which the 1986 Act does apply is now 35 years out of date; it excludes the national Health Service Executive, for example, and the Child and Family Agency which holds approximately 70,000 adoption records deriving from its predecessors’ activities and from now-defunct adoption agencies and Mother and Baby institutions. (69)

Local authority records also fall outside the remit of the National Archives Act 1986,85 as do the records of the Adoption Authority of Ireland (previously the Adoption Board). (70) (71)

Public access is constrained even to those state departmental records that should be available in the National Archives of Ireland (NAI) because government funding to the NAI is so low that its archivists are only capable of actively managing four government departments’ records and over one third of the NAI’s limited holdings are not catalogued. (72) (73)

The Freedom of Information Act 2014, meanwhile, creates a general right of access only to information held by public bodies that was created after 1998 (or 2008 for some public bodies) with narrow exceptions. (74)

The 2014 Act specifically excludes from its remit adoption records held by the Adoption Authority of Ireland. (75)

Decision-makers’ discretion under the 2014 Act may be deployed to prevent access; Ó Fátharta, a journalist writing extensively on twentieth-century adoptions in and from Ireland, explains that the 2014 Act is becoming less useful to his research the more that the abuses in the adoption system are coming to public attention:

‘Access to information is everything to a journalist. … I would say in the last four or five years it has become far more stringent …You don’t get anything back on time, there’s so many ways to drag it out. … I’ve said this before: on all of the adoption stuff that I’ve done, I was accessing records to do with Mother and Baby Homes pretty easily through the HSE [Health Service Executive] and Tusla. I understand there are things you can’t get. Then lo and behold, since a lot of this stuff started to get more traction, I get nothing now.’ (76)

For many years, the government rejected survivors’ and advocates’ requests for legislation compelling the production of all historical ‘care’-related records into a dedicated national archive. Ireland informed the CAT in 2018 that the nuns’ records relating to Magdalene Laundries ‘are in the ownership of the religious congregations and held in their private archives [and] the State does not have the authority to instruct them on their operation.’ (77)

This echoed a statement by the Minister for Justice in 2013 that:

‘I have no control over records held by the religious congregations or other non-State bodies. … It is not within my power to establish a facility that would allow the women who were admitted to the Magdalen Laundries and their families access to all genealogical and other records necessary to locate their families and reconstruct their family identities.’93 (78)

In October 2020 the government finally announced that it will in the future create ‘on a formal, national basis an archive of records related to institutional trauma during the 20th century.’ (79)

This announcement followed public pressure campaigns fought vigorously by survivor- and adopted-person-led groups in response to a government Bill in 2019 proposing to ‘seal’ for at least 75 years the archive of the largest statutory investigation to date on matters of historical church-related institutional child abuse, and the government’s announcement in September 2020 that it intended to ‘seal’ for 30 years the archive gathered by the MBHCOI. (80) (81)

At present, the Department of the Taoiseach (Prime Minister) has custody of the entire archive of state administrative records concerning the Magdalene Laundries. These were gathered from numerous departments for the purpose of an Inter-Departmental Committee (IDC) examination between 2011 and 2013 of the state’s historical interactions with the institutions. (82)

For years the Taoiseach’s Department insisted in response to Freedom of Information requests that: ‘these records are stored in this Department for the purpose of safe keeping in a central location and are not held nor within the control of the Department for the purposes of the FOI Act. They cannot therefore be released by this Department.’ (83)

Following legal proceedings by one survivor, the Information Commissioner found this stance unlawful. (84)

Nonetheless, the archive has not been deposited in the NAI nor made publicly available otherwise. The state argued as recently as July 2020 to the CAT that Elizabeth Coppin should try to piece together her own version of the Taoiseach’s collected archive of Magdalene Laundry records by making individual requests to all of the original record holders using the Freedom of Information Act (which, as discussed above, does not apply generally to historical information). (85)

The MBHCOI archive, which the Minister for Children announced his intention to ‘seal’ in September 2020, similarly rests in a government Department without any clear pathway to accessing it. Its contents are known to include financial, inspection, maternity, death and burial, adoption, statistical, research, baptism and other records of Mother and Baby institutions and related agencies, government departments, religious congregations, churches and dioceses, local authorities, foreign adoption societies, pharmaceutical companies, university anatomy departments, and cemeteries, for example. (86)

Finally, victims’ and survivors’ access to their personal data and to information about deceased or disappeared next of kin is stymied both by the absence of an explicit, detailed legislative scheme of personal access to historical care-related records and by the ad hoc, legally dubious decision-making of the wide range of state and non-state actors that hold relevant records and are subject to the European Union General Data Protection Regulation framework. (87)

The CLANN Project has reported numerous incidences of mothers, adopted people and others affected by family separation being discouraged, delayed, demeaned and even lied to in their search for personal information in recent decades. (88)

In 1997 the St Patrick’s Guild adoption agency, which arranged more than 10,000 adoptions in Ireland during the twentieth century, acknowledged that it routinely gave false information to adopted people about their parents. (89)

In summer 2019 a government-appointed Collaborative Forum of survivors of Mother and Baby Homes reported being informed by Tusla that when an adopted person requests their personal records, state social workers assess ‘the likelihood of harm being caused to wider birth families by the release of personal information to an applicant.’ (90)

The Collaborative Forum noted that ‘[n]either the statutory basis for such a criterion, nor the nature of how harm is determined, was clear to forum members.’ (91)

Tusla has further stated as a blanket rule that when an adopted person seeks information it can only ‘lawfully release information relating to other persons (e.g. birth parents) with their expressed consent,’ demonstrating that Tusla does not consider an adopted person’s identity at birth or family circumstances to be their personal data. (92) (93)

The opaque and unpredictable manner in which the state manages the personal information of people subjected to unlawful family separation was further demonstrated in 2018 when the Department of Children publicly acknowledged (having been aware of many of these cases for several years) that it knew of 126 people registered at birth by an adoption agency as the natural child of people who were not their natural parents. (94) (95)

Records of internal departmental discussions show the question being raised, ‘whether the information will do more harm than good to those who have no indication of the problem to date,’ and Tusla querying ‘who to tell first – birth parents, adopted parents, subject of registration’; ‘how much information are they entitled to’; ‘if the subject matter is deceased, do we advise their children’; and ‘how does the state manage litigation?’ (96)

NOTES

- Dáil Éireann Debates, ‘Magdalen Laundries Report: Statements’, 19 Feb. 2013, https://www.kildarestreet.com/debates/?id=2013-02-19a.387.

- ‘“Ireland failed you”: President Higgins apologises to Magdalene Laundries survivors at Aras an Uachtarain event’, The Irish Examiner, 5 June 2018, https:// irishexaminer.com/breakingnews/ireland/ireland-failed-you-president-higgins-apologises-to-magdalene-laundries-survivors-at-aras-an-uachtarain-event-846951. html.

- Juno McEnroe, ‘Magdalene Redress: Official Ireland took its time with apology, admits Charlie Flanagan’, The Irish Examiner, 6 June 2018, https://www. com/ireland/magdalene-redress-official-ireland-took-its-time-with- apology-admits-charlie-flanagan-471525.html

- See for a summary of publicly available evidence and official reports, Maeve O’Rourke, ‘Justice for Magdalenes Research, NGO Submission to the UN Committee against Torture’ (Justice for Magdalenes Research, 2017),pp 7–15, https://tbinternet.ohchr.org/_layouts/15/treatybodyexternal/Download.aspx?symbol no=INT%2fCAT%2fCSS%2fIRL%2f27974&Lang=en; See also Maeve O’Rourke and James M Smith, ‘Ireland’s Magdalene Laundries: Confronting a History Not Yet in the Past’, in Alan Hayes and Maire Meagher (eds), A Century of Progress? Irish Women Reflect (Dublin, 2016).

- See for the most recent example: Ireland, Information on follow-up to the concluding observations of the Committee against Torture on the second periodic report of Ireland, UN Doc CAT/C/IRL/CO/2/Add.1, 28 Aug. 2018, para 15.

- See for one example of this repeated statement: Ireland, Replies to the Human Rights Committee’s List of Issues, UN Doc CCPR/C/IRL/Q/4/Add.1, 5 May 2014, para

- Ireland, Replies to the List of Issues Prior to Submission of the Second Report of Ireland, UN Doc CAT/C/IRL/2, 20 2016, para 237.

- Against Torture (CAT), Elizabeth Coppin v. Ireland, Communication No 879/2018, Submission of the Government of Ireland on the Merits of the Communication to the Committee Against Torture Made by Elizabeth Coppin, 31 July 2020, para 115 (on file with author).

- Most recently, Irish Human Rights and Equality Commission, Submission to

the United Nations Committee against Torture on Ireland’s Second Periodic Report, July 2017, pp 53–8.

- Committee Against Torture (CAT), Concluding Observations on the First Periodic Report of Ireland, UN Doc CAT/C/IRL/CO/1, 17 June 2011, para 20; CAT, Concluding Observations on the Second Periodic Report of Ireland, UN Doc CAT/C/IRL/CO/2, 31 2017, para 25; Human Rights Committee (HRC), Concluding Observations on the Fourth Periodic Report of Ireland, UN Doc CCPR/C/IRL/CO/4, 19 Aug. 2014, para 10; Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW), Concluding Observations on the Combined Sixth and Seventh Periodic Reports of Ireland, UN Doc CEDAW/C/ IRL/CO/6–7, 3 Mar. 2017, paras 14–15; Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (CESCR), Concluding observations on the third periodic report of Ireland, UN Doc E/C.12/IRL/CO/3, 19 June 2015, para 18; Report of the Special Rapporteur on the sale and sexual exploitation of children, UN Doc A/HRC/40/51/ Add.2, 1 Mar. 2019, paras 16–19, 78.

- See for example Maeve O’Rourke, Claire McGettrick, Rod Baker, Raymond Hill et al., CLANN: Ireland’s Unmarried Mothers and their Children: Gathering the Data: Principal Submission to the Commission of Investigation into Mother and Baby Homes, 15 Oct. 2018 (hereafter CLANN Report), http://clannproject.org/wp- content/uploads/Clann-Submissions_Redacted-Public-Version-Oct.-2018.pdf

- CAT (2017), paras 27–28 (n. 10); CEDAW (2017), above para 15 (n. 10); HRC

(2014) above para 10 (n. 10).

- CLANN Report, para 37 (n. 11).

- See Child and Family Agency, St Patrick’s Guild Adoption Records, https://www. ie/services/alternative-care/adoption-services/tracing-service/st-patricks-guild- adoption-records/; Department of Children, Draft Heads and General Scheme of Birth Information andTracing Bill, 11 May 2021, https://www.gov.ie/en/press-release/14c5c- minister-ogorman-publishes-proposed-birth-information-and-tracing-legislation/.

- See Aoife Hegarty, ‘Who am I? The Story of Ireland’s Illegal Adoptions’ RTÉ Investigates, 5 Mar. 2021, https://www.rte.ie/news/investigations- unit/2021/0302/1200520-who-am-i-the-story-of-irelands-illegal-adoptions/; Marion Reynolds, A Shadow Cast Long: Independent Review Report into Incorrect Birth Registrations: Commissioned by the Minister for Children and Youth Affairs, May 2019, https://www.gov.ie/pdf/?file=https://assets.gov.ie/126409/d06b2647-6f8e-44bf- 846a-a2954de815a6.pdf#page=null.

- Conall Ó Fátharta, ‘Special Report: Women Forced to Give up Babies for Adoption Still Failed by State bodies’, The Irish Examiner, 3 2018.

- CLANN Report, para 47 (n. 11).

- Ibid., para 49.

- Ibid., para 42.

- , para 1.91.

- , para 1.159.

- Ibid., para 84.

- , para 1.54–1.55.

- , para 1.172–1.173.

- , para 1.208.

- , para 1.224.

- , para 1.225.

- Mother and Baby Homes Commission of Investigation [hereafter MBHCOI], Final Report, 2020, https://assets.gov.ie/118565/107bab7e-45aa-4124-95fd- 1460893dbb43.pdf [hereinafter MBHCOI Final Report].

- , Exec. Summary para 8.

- , Recommendations para 27.

- , Recommendations para 30.

- , Recommendations para 34.

- , Exec. Summary para 248.

- , Ch. 36 para 248.

- pt. 4. (Confidential Committee Report), p. 12. Ibid., 10, the MBHCOI explains that only nineteen people gave evidence to the investigative arm of the Commission (which had powers to make adverse findings against institutions or individuals) whereas 550 met the Confidential Committee (which had the power only to make a report of a general nature). In Aug. 2016 Hogan Lovells International LLP wrote to the MBHCOI on behalf of the Clann Project noting with concern that ‘the Commission’s rules and procedures, which identify the two ways to give evidence, are not shown on the website and there is no mention of being able to give direct evidence in person to the Commission other than via the Confidential Committee’: see Rod Baker, Hogan Lovells International LLP, ‘Letter to Maeve Doherty, Mother & Baby Homes—Commission of Investigation’, 9 Aug. 2016, http://clannproject. org/wp-content/uploads/Letter-from-Hogan-Lovells-to-MBHCOI_09-08-2016.pdf

- MBHCOI Final Report, Part 4, Confidential Committee Report, 12.

- Committee Against Torture, Concluding Observations on the Second Periodic Report of Ireland, N. Doc. CAT/C/IRL/CO/2, 31 Aug. 2017, para 26–28.

- See the numerous Concluding Observations at 10.

- O’Rourke, ‘NGO Submission’, para 1 (n. 4).

- See Ireland, Information on Follow-up to the Concluding Observations of the Committee against Torture on the Second Periodic Report of Ireland, para 19 (n. 5); Committee Against Torture, Information received from Ireland on the implementation of the Committee’s concluding observations, N. Doc. CAT/C/IRL/CO/1/Add.1, 22, 31 July 2012; Ireland, Replies to the Human Rights Committee’s List of Issues, para 57 (n. 6); Ireland, Follow-Up Material to the Concluding Observations of the UN Human Rights Committee on the Fourth Periodic Review of Ireland under the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, 17 July 2015, p. 3, https://tbinternet.ohchr. org/_layouts/15/treatybodyexternal/Download.aspx?symbolno=INT%2fCCPR%2f AFR%2fIRL%2f21460&Lang=en; Ireland, Second Periodic Report to the Committee Against Torture, UN Doc CAT/C/IRL/2, 20 Jan. 2016, para 241, https://tbinternet. ohchr.org/_layouts/15/treatybodyexternal/Download.aspx?symbolno=CAT%2 fC%2fIRL%2f2&Lang=en; Ireland, Combined sixth and seventh periodic reports to the United Nations Committee on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women, U.N. Doc. CEDAW/C/IRL/6–7, 30 Sept. 2016, para 43; Ireland, Information on follow-up to the concluding observations of the Human Rights Committee on the fourth periodic report of Ireland, UN Doc CCPR/C/IRL/CO/4/Add.1, 15 Aug. 2017, para 6.

- Information on Follow-up to the Concluding Observations of the Committee Against

Torture on the Second Periodic Report of Ireland, para 18 (n. 5).

- According to the Adoption Rights Alliance group and Mike Milotte, the only known prosecution of an adoption agency is in 1965 at the Dublin District Court, where the manager of a private nursing home, Mary Keating, was convicted for registering births falsely; Keating continued her operations for more than a decade See CLANN Report, para 1.117 (n. 11), citing Mike Milotte, Banished Babies:The Secret History of Ireland’s Baby Export Business (Dublin, 2012), p. 126.

- , para 2.19 (the testimony of a witness).

- See Kevin Doyle, ‘Charges are “not Likely” After Garda Probe Into Adoptions’,

The Irish Independent, 1 June 2018.

- Conall Ó Fátharta, ‘Bessborough Report Referred to Gardaí’, The Irish Examiner, 24 2019; MBHCOI, Fifth Interim Report, 2019, para 8.38, https://www.gov. ie/en/press-release/169f8f-commission-of-investigation-into-mother-and-baby- homes-fifth-interim/ [hereinafter MBHCOI Fifth Interim Report].

- Oireachtas Joint Committee on Children, Disability, Equality and Integration, General Scheme of a Certain Institutional Burials (Authorised Interventions) Bill: Discussion, Evidence of Anna Corrigan, 14 Apr. 2021, https://www.oireachtas. ie/en/debates/debate/joint_committee_on_children_disability_equality_and_ integration/2021-04-14/3/.

- ‘Appealfor Information About Crimesat Mother-and-Baby Homes’, RTÉNews, 29 2021, https://www.rte.ie/news/mother-and-baby-homes/2021/0429/1212798– mother-baby-appeal/.

- An Garda Síochána, Press Release, ‘Garda Appeal re Mother and Baby Homes’, 29 Apr. 2021, https://www.garda.ie/en/about-us/our-departments/office-of- corporate-communications/press-releases/2021/Apr./garda-appeal-re-mother-and- baby-homes.html.

- See Commissions of Investigation Act 2004, section 19, http://www. ie/eli/2004/act/23/section/19/enacted/en/html#sec19. This legislation underpinned the MBHCOI and specifies that no ‘statement or admission’ made to the MBHCOI, nor ‘document given or sent to [the MBHCOI] pursuant to a direction or request’, nor ‘document specified in an affidavit’ is admissible as evidence against a person in any criminal or other proceedings.

- Oireachtas Joint Committee on Children, Disability, Equality and Integration, General Scheme of a Certain Institutional Burials (Authorised Interventions) Bill, Discussion, Evidence of Anna Corrigan, (n. 47).

- James Gallen, Historical Abuse and the Statute of Limitations 39 Statute Rev., 2016, p. 104.

- p. 109. The ‘disability’ exception to the running of the limitation period applies only if (a) the person is ‘of unsound mind’, or (b) the person’s court action is based on sexual abuse suffered in childhood, which caused a ‘psychological injury’ of ‘such significance that his or her will, or his or her ability to make a reasoned decision, to bring such action [was] substantially impaired Statute of Limitations Act 1957 (as amended by Statute of Limitations (Amendment) Act 2000), section 48A.

- O’Dwyer The Daughters of Charity of St Vincent de Paul & Ors [2015] IECA 226 (Court of Appeal) para 45. See also EAO v. Daughters of Charity of St.Vincent de Paul & Ors [2015] IEHC 68 (High Court); Elizabeth Anne O’Dwyer v.The Daughters of Charity of St.Vincent de Paul, the Sisters of Our Lady of Charity of Refuge, and the Health Service Executive [2016] IESCDET 12 (unreported), 22 Jan. 2016, (Supreme Court).

- O’Keeffe Ireland (2014) 59 EHRR 15.

- Mary Carolan, ‘State Awarded Costs in School Abuse Case’, The Irish Times, 24 2006; O’Keeffe v. Ireland, paras 27, 47 (n. 70).

- Colin Smith and Duff, chapter 8 in this volume..

- O’Rourke, NGO Submission, 16 (n. 4)

- MBHCOI Final Report, Index, 39 (n. 29)

- Exec. Summary, para 229, 243. See also Ibid., Ch. 33A, p. 6, observing that ‘[m]ortality rates in each of the institutions were very high in the period compared to the overall national rate of infant mortality’. The higher-than-average rate of mortality continued into the 1980s, Ibid., ch 33A, p. 11.

- Sarah-Anne Buckley, Vicky Conway, Máiréad Enright, Fionna Fox, James

Gallen, Erika Hayes, Mary Harney, Darragh Mackin, Claire McGettrick, Conall Ó Fátharta, Maeve O’Rourke & Phil Scraton, Joint Submission to Oireachtas Committee on Children, Equality, Disability and Integration RE: General Scheme of a Certain Institutional Burials (Authorised Interventions) Bill 26 Feb. 2021, pp 23–26, http:// jfmresearch.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Institutional-Burials-Bill_Joint- Submission-26.2.21.pdf

- Coroners Act 1962 (as amended), § 17, https://revisedacts.lawreform.ie/eli/1962/ act/9/front/revised/en/html.

- , section 24(1).

- Buckley, et al, Joint Submission, 7 (n. 63).

- MBHCOI, Fifth Interim Report, 65 (n. 46).

- See National Archives Act 1986 (as amended), sections 1, 2, 13, which establish that ‘public service organisations’ (a local authority, health board, or body established by or under statute and financed wholly or partly by the state) may but are not required to deposit records with the National The National Archives Act 1986 says nothing about the records of non-state bodies which provide state-funded services.

- Reynolds, Shadow Cast Long, paras 11, 2.1, 4.13 (n. 16).

- They are subject to the Local Government Act 2001 section 80(2), which simply states that ‘it is a function of a local authority to make arrangements for the proper management, custody, care and conservation of local records and local archives and for inspection by the public of local archives’.

- These bodies are not listed in the Schedule to the National Archives Act The Adoption Authority of Ireland holds approximately 30,000 adoption records including those created by four former adoption agencies or societies: Reynolds, Shadow Cast Long, para 3.3 (n. 16).

- Creative Cultures and Associates, National Archives, Ireland: A Comparative Management Survey for Fórsa, Archivists’ Branch, 2019, p. 22, https://www.forie/ wp-content/uploads/2019/12/Forsa-NAI-final-2.pdf

- Ibid., 35.

- See Freedom of Information Act 2014, sections 2, 11. The exception is where disclosure of older records is necessary or expedient to understand the more recent records or where the older records ‘relate to personal information about the person seeking access to them’. Freedom of Information Act 2014, section 11.

- , Schedule 1.

- Conall Ó Fátharta, Tony Groves & Martin McMahon, ‘Illegal Adoptions’, Echo Chamber Podcast, Episode 163, 31 May

- Ireland, Information on follow-up to the Concluding Observations of the Committee against Torture, N. Doc. CAT/C/IRL/CO/2/Add.1, para 28 (n. 5).

- Dáil Éireann Debates, ‘Magdalen Laundries’, Written Answer by Minister for Justice and Equality, Alan Shatter TD, 6 Mar. 2013, https://www.oireachtas.ie/en/ debates/question/2013-03-06/170/.

- Irish Government News Service, Government Statement on Mother and Baby Homes, 28 Oct. 2020, https://merrionstreet.ie/en/news-room/news/government_ html.

- Justice for Magdalenes Research, Campaigns, Retention of Records Bill 2019, http://jfmresearch.com/retention-of-records-bill-2019/. This campaign was in response to the Retention of Records Bill 2019 (as initiated), https://data.oireachtas. ie/ie/oireachtas/bill/2019/16/eng/initiated/b1619d.pdf

- Justice for Magdalenes Research, Campaigns, Mother and Baby Homes Commission Archive, http://jfmresearch.com/commission-archive/. This campaign followed Press Release, Ireland, Department of Children, Equality, Disability, Integration and

Youth, Minister O’Gorman to Introduce Legislation to Safeguard the Commission on Mother and Baby Homes General Archive of Records and Database, 15 Sept. 2020, https://www.gov.ie/en/press-release/96a99-minister-ogorman-to-introduce- legislation-to-safeguard-the-commission-on-mother-and-baby-homes-general- archive-of-records-and-database/.

- Ireland, Report of the Inter-departmental Committee to Establish the Facts of State Involvement with the Magdalen Laundries (hereafter IDC Report), 2013, http://www.justice.ie/en/jelr/pages/magdalenrpt2013.

- O’Rourke, ‘NGO Submission’, para 15–16 (n. 4).

- Ms P and Department of the Taoiseach, Office of the Information Commissioner, Case Number: OIC-53487-S3Q7X3, 24 Jan. 2020, https://www.oic.ie/decisions/ms- p-and-department-of-th/.

- Committee Against Torture, Elizabeth Coppin v Ireland, Communication No 879/2018, Submission of the Government of Ireland, para 156 (n. 23).

- MBHCOI Final Report, Archives (n. 29).

- Maeve O’Rourke, Loughlin O’Nolan & Claire McGettrick, Joint Submission to the Oireachtas Joint Committee on Justice regarding the General Data Protection Regulation, 26 2021, http://jfmresearch.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Submission-to- Oireachtas-Justice-Committee-Re-GDPR-MOR-CMG-LON-26.3.21.pdf

- See CLANN Report, para 45, 3.58 (n. 11)

- Padraig O’Morain, ‘Adoption Society Admits Supplying False Information to Shield Mothers’ Identities’, The Irish Times, 7 1997.

- Conall Ó Fátharta, ‘Tusla Considers Damage Release of Personal Information Can Cause’, The Irish Examiner, 16 July 2019.

- Regarding mixed personal data, see Dr B The General Medical Council [2016] EWHC 2331 (QB).

- Conall Ó Fátharta, ‘Adoption Body Reported Illegal Record in 2002’, The Irish Examiner, 18 June

- See Sean Murray, ‘Adoption Scandal: Officials Questioned Whether Telling Those Affected Would “Do More Harm Than Good”’, ie, 6 July 2018.