Attempts to gain Leon Trotsky asylum in the Irish Free State

By Jack Traynor

Leon Trotsky was one of the most recognisable leaders of the Bolshevik Revolution in the international press, alongside Vladimir Lenin. He played a decisive role in the creation and solidification of the new Bolshevik regime in Russia, particularly in his capacity as people’s commissar for military affairs of the Red Army during the Russian Civil War, 1917-23.

Considered a likely successor to Lenin, Trotsky was ultimately thwarted by Joseph Stalin during the power struggle which emerged immediately after Lenin’s untimely death in January 1924.

The international press, including Irish newspapers, maintained an interest in the charismatic Trotsky whose revolutionary politics ensured he retained a whiff of sulphur in the West.

Readers of the Cork Examiner in January 1925 were treated to the description of Trotsky as ‘a man of infinite resource. He is a born leader, and his ambition is illimitable. If he escapes the Cheka and recovers his health, he may yet reveal himself as the new Dictator, if not the Napoleon Buonaparte, of a rediscovered Russia.’[1]

The Irish war correspondent Francis McCullagh was in Russia following the Bolshevik victory there: ‘he would have been within feet of both Lenin and Trotsky… Some of [McCullagh’s] articles bespeak a grudging admiration of the latter, always tempered by his antipathy to Trotsky’s anti-religious activities, and on occasion disfigured by an unsavoury tinge of anti-Semitism.’[2]

Leon Trotsky was exiled from the Soviet Union by Stalin in 1929 and subsequently sought aslylum in various countries

Press interest in the ‘Red Bonaparte’ continued unabated following his expulsion from Soviet territories in 1929. They reported on his subsequent interlope across Turkey, France, Norway, and finally Mexico.

Trotsky sought refuge in various countries, including important Western nations such as France, Germany, and the United Kingdom. The Irish labour leader William O’Brien petitioned the Free State government of William T. Cosgrave to grant shelter to the exiled Trotsky in 1930, however the arch-conservative Cosgrave was unwilling to countenance accepting such a request.

Meanwhile, British left-wing politicians and Trotskyist fellow travellers unsuccessfully tried to persuade the Labour government of Ramsay MacDonald to grant the exiled Soviet revolutionary asylum in Britain. Following their failure in Britain, they refocussed their efforts towards securing Trotsky’s asylum in the neighbouring Irish Free State, where they hoped the new Fianna Fáil government may be more sympathetic to the ex-Bolshevik leader’s plight.

Trotsky’s exile

In 1929, Trotsky was exiled from the Soviet Union and granted asylum in Turkey by the government of Kemal Atatürk. Whilst living on the island of Büyükada, the largest of the Prinkipo Islands south of Istanbul[3], international supporters and sympathisers continued their efforts to find a country willing to accept him, such as Germany or France, where he could be closer to his supporters in the anti-Stalinist opposition.[4]

A telegram from the exile to Paul Löbe, the Social Democrat President of the Reichstag, requested a visa to enter Germany. The Irish Independent noted ‘If Herr [Löbe] can persuade his Cabinet to grant asylum to Trotsky, he will be making trouble with Stalin.’[5]

In April, the Belfast Newsletter reported ‘a rude shock for Trotsky’ upon learning that his application was rejected, despite ‘efforts made on his behalf by many high placed sympathisers in Germany.’ ‘The Soviet chiefs… approached the German Government suggesting that Trotsky’s presence in Germany would not be favourably received by them.’[6] Western governments’ fear of needlessly antagonising Stalin and souring relations with the Soviet Union became a recurring reason for the rejection of Trotsky’s many asylum pleas.

William O’Brien lobbies Cosgrave

The first representation made on Trotsky’s behalf in Ireland came from the labour leader William O’Brien in 1930. That year, the Irish Labour Party had parted ways with the Trade Union Congress. O’Brien supported this move, believing the separation would attract more non-trade unionists to the political Labour Party, although he remained active in both movements.[7]

An Alderman of Dublin Corporation and previously a TD in the Free State parliament, O’Brien told a Sligo audience of trade unionists in March that Irish workers must follow the ‘lead [of]… British workers… who return[ed] to power a [L]abour Government of Westminster.’[8]

O’Brien had been interned on two occasions during the Irish independence struggle, had been on hunger strike and helped to organise general strikes against British militarism in 1918 and 1920. However, his reformist streak was obvious from his support for the 1921 Anglo-Irish Treaty and his acceptance and participation in the institutions of the Irish Free State from 1922 onwards. His treatyite views somewhat ingratiated the labour leader to the President of the Executive Council, William T. Cosgrave.

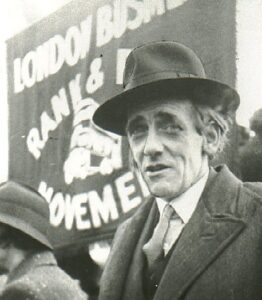

Irish Labour leader William O’Brien lobbied the Irish Free State premier W.T. Cosgrave to have Trostky given asylum in the Free State, in part out of antipathy to the Moscow-supporting Jim Larkin.

In January 1923 Jim Larkin was released from a New York prison. Upon his return to Ireland in April, he began to agitate against O’Brien, whose reformism he despised and whose position as head of the Transport Union, which O’Brien had risen to in his absence, he wanted to recover. Larkin split the union in 1924, forming his own Workers’ Union of Ireland.

Their protracted rivalry spanned the 1920s and 1930s and reflected, as well as personal antipathy, the divisions then happening within the international left-wing on the issue of reform versus revolution. Larkin, who represented the latter tendency, gained official affiliation for his Irish Worker League from the Comintern and was supported by the Soviet Union.[9]

Whilst under Soviet influence, Larkin’s Irish Worker newspaper repeated the Moscow line, claiming in January 1932 that ‘Stalin… did a great service to the workers of the world when he exiled Trotsky.’[10] Likely as a reaction against the Larkin/Soviet alliance, O’Brien supported Irish asylum for Trotsky in 1930. If the Free State were to give refuge to the leader of the anti-Stalinist opposition at O’Brien’s instigation, it would represent a victory for O’Brien over Larkin. In fact, by 1928 Larkin had quietly begun to drift away from Soviet orthodoxy, a disentanglement which became obvious ‘to all who cared to notice’ by 1934.[11]

In Autumn 1930, O’Brien approached Cosgrave to ask the Cumann na nGaedheal government to consider granting the exile asylum in the Irish Free State. Unsurprisingly, Cosgrave was wholly against honouring such a request. In a brief, Cosgrave recorded his back-and-forth with O’Brien on the merits and demerits of granting Trotsky refuge:

‘I could see no reason why Trotsky should be considered by us. Russian bonds had been practically confiscated. He [O’Brien] said there was to be consideration of them. I said it was not by Trotsky, whose policy was the reverse. I asked his nationality. Reply Jew. They were against religion (he said that was modified). I said not by Trotsky. He said he had hoped there would be an asylum here as in England for all. I agreed that under normal conditions, which we had not here, that would be alright. But we had no touch with this man or his Government, nor did they interest themselves in us in his ‘day’.’[12]

Dermot Keogh noted the assumed anti-Semitic undertones inherent in Cosgrave’s refusal, namely the attention he paid to Trotsky’s being a Jew.[13]

Throughout the 1930s, the anti-communist fervour of Catholic Ireland occasionally overlapped with an overt hostility to Jews, as seen in a lecture (‘The Red Revolution in Russia’) delivered by the Catholic priest Denis McDaid in 1937 (whose words were reprinted in local newspapers across Ireland). Fr. McDaid claimed: ‘The men who pose as the representatives of the Russian proletariat… very many of them are not Russians, but Jews’. He then revealed that ‘some of the leading personalities… Trotsky, Zinoviev, Kamenev’ were in fact ‘Bronstein, Apfelbaum, Rosenfeld.’[14]

Cosgrave saw, ‘no reason why Trotsky should be considered by us.. nor did [he] interest himself in us in his day’.

Irrespective of any assumed anti-Semitism, Cosgrave’s decision dashed any hope of Trotsky receiving refuge in the deeply conservative Free State. O’Brien’s support for Trotsky’s asylum did not mean he shared Trotsky’s revolutionary socialism. Rather, O’Brien strategically sought to undermine Larkin with whom he was locked in a bitter political and ideological feud which bore international significance. The issue of Trotsky’s prospective asylum in Ireland was not revived until 1934.

Trotsky’s British supporters

In Britain, the Labour Party came to power in June 1929, heartily welcomed by O’Brien. Some of Trotsky’s supporters believed the minority government may be more amenable to granting the erstwhile Bolshevik leader entry to Britain than the previous Conservative administration.

Ramsay MacDonald’s new government received an application for a visa for Trotsky on 10 June submitted on his behalf by Labour MP Ellen Wilkinson.[15] In early June, a Turkish newspaper erroneously reported that Trotsky had ‘received permission from Mr. Mac[D]onald to visit England’.

This rumour spread throughout the international press, including in Ireland.[16] In truth, the British government believed there were ‘strong reasons against giving shelter to M[r.] Trotsky’. The cabinet agreed on 26 June that ‘for the moment no action should be taken.’[17]

However, simply ignoring Trotsky’s application would not make the issue go away. Parliamentarians from the government party (including Sir George Penny, Sir John Power, and Colonel Josiah Wedgwood) alongside prominent members of the Independent Labour Party, including MPs James Maxton and John McGovern, pressured the government to move forward with Trotsky’s application.

A Labour-led government in Britain also turned Trotsky down for asylum in 1930.

The ILP confirmed to home secretary John Robert Clynes that Trotsky promised ‘not to interfere… in the affairs of this country, to reside at any place which the Authorities might select, and to submit to any surveillance which might be deemed necessary.’ They also informed Clynes that they had invited Trotsky to present a lecture to the ILP summer school that year.[18] A decision could not be postponed any longer.

On 24 August, the home secretary explained to his cabinet colleagues the ‘over-whelming… arguments against giving shelter to Trotsky.’ Clynes correctly claimed that Trotsky had ‘made no application to come to the United Kingdom until after the General Election and his reason for applying now… [is] that he hopes for a favourable decision from the New Government.’

The Labour government was strongly averse to being levelled with the accusation of communist sympathies, especially as in 1924 MacDonald’s first short-lived government was roundly defeated in that year’s October general election following the publication of the forged ‘Zinoviev letter.’

This forgery was purportedly written by Comintern chief Grigory Zinoviev and expressed the view that the Labour Party’s re-election would prove a catalyst for the radicalisation of British politics and would advance Soviet interests. Clynes also feared that Trotskyists in Germany and France ‘would be encouraged and strengthened by the apparent support given to him by the British Government.’[19]

The home secretary believed that to grant Trotsky asylum would likely ‘be regarded as an unfriendly act by the Soviet Government’ who ‘might allege that the British government has given hospitality to Trotsky for political reasons and was using him as a means of weakening the position of the existing Government in Russia.’

Similarly, since he had been refused asylum by the governments of France, Germany, Belgium, and Norway, for the British to grant him admission it ‘might also be interpreted… as an adverse reflection of their refusals to admit him.’ Clynes further worried that admitting Trotsky would set a precedent for ‘a flood of other aliens and refugees’ to seek refuge in Britain from the Stalinist regime.[20]

In a speech to the House of Commons on 18 July, Clynes claimed that if allowed to enter Britain, ‘persons of mischievous intention would unquestionably seek to exploit [Trotsky’s] presence for their own ends’ whilst the British government would find it impossible to rid themselves of their troublesome guest should the need ever arise as they ‘could have no certainty of being able to secure his departure’ due to the Soviet government’s inevitable refusal to accept his deportation to Russia.[21]

Accordingly, the British government rejected Trotsky’s visa application. At the Independent Labour Party’s 1929 summer school (without Trotsky), James Maxton voiced his disappointment with the Labour government and claimed if he were prime minister he would have ‘recognised Russia and admitted Trotsky into Britain.’[22] Although the issue of Trotsky’s possible asylum in Britain was raised again in parliament in 1930 and 1931 by Labour MPs, Clynes clung to the original decision: ‘[t]here can be no question of any departure from the decision taken nearly two years ago.’[23]

In Trotsky’s 1937 book on the Soviet Union post-1924, The Revolution Betrayed, which served as his comprehensive denunciation of Stalinist totalitarianism in the Soviet Union, the author vituperatively criticised the socialist theoretician and Labour politician Sidney Webb (Lord Passfield) for producing works defending the Soviet Union ‘from being undermined’ whilst ‘practically… defending the Empire of His Majesty’ by serving as a minister in Ramsay MacDonald’s government which denied Trotsky asylum.[24]

Trotsky’s British supporters and Ireland

James Maxton and John McGovern of the Independent Labour Party strongly admired the President of the Executive Council, Éamon de Valera, and forged a cordial relationship with the Fianna Fáil leader.

Elected in February 1932, de Valera was often depicted by his political enemies, mostly in Cumann na nGaedheal, as an ‘Irish Kerensky’ whose government was backed by the ‘shadow of the gunman’ in the IRA, who at that time had adopted strongly left-wing rhetoric. According to this depiction, de Valera was paving the way for a more radical revolutionary takeover of power.[25]

In March 1932, the new government suspended the Public Safety Act which lifted bans on various radical organisations including the IRA, Saor Éire, and the Communist Party of Ireland.

An important electoral pledge of Fianna Fáil had been to withhold payment of the Land Annuities, sums collected by the Free State from Irish farmers to repay the historic sums lent to them by the British government to purchase their holdings under the terms of the ‘John Bright Clauses’ of the Landlord and Tenant (Ireland) Act, 1870. When the new government implemented this pledge, the Anglo-Irish trade war erupted between the fledgling Fianna Fáil-led government and Britain in 1932.

Members of the Independent Labour Party in Britain, sympathetic to Irish Republicanism, thought the de Valera government in Ireland after 1932 would look more kindly on Trotsky than the Cosgrave government.

In January 1934, Maxton and McGovern visited Ireland to investigate the effects of the trade war. Whilst in Ireland, Maxton met de Valera on 18 January[26] and voiced his approval for Fianna Fáil’s stance on the Economic War: ‘We are convinced of the right and justice of [de Valera’s] policy.’[27]

James Dillon, a TD from the recently founded Fine Gael (the United Ireland Party), seized the opportunity to attack the government for alleged association with the ‘Communist-Socialist agitator’ Maxton. Addressing an Athlone audience, Dillon declared: ‘If the policy of Fianna Fáil commended itself to James Maxton every Catholic workingman in the country ought to leave Fianna Fáil.’[28]

Meanwhile, the unionist Belfast Newsletter observed that ‘Mr. McGovern, at all events, should find in Mr. De Valera a kindred spirit.’[29] As socialist internationalists their sympathies lay with the Irish government. In late January, Maxton informed a London audience of the Civil Service Clerical Association:

‘British people may talk conventionally of Ireland being part of the British Empire, but the truth is that it is gone in every sense of the term. The last economic link was broken when the present Dominions Secretary started the boycott on Irish cattle.’[30]

Maxton and McGovern’s relationship with de Valera reached its zenith in early 1934, as the Irish leader was deeply grateful for their outspoken support of his government’s position. John McNair, an ILP contemporary, recalled ‘[Maxton] had always been on friendly terms with de Valera with whom he had many qualities and ideas in common. Both men had been rebels all their lives.’[31]

However, de Valera’s ‘rebel’ nature was tempered by a deeply conservative streak which would soon become apparent when Maxton and McGovern sought to secure asylum for Trotsky in the Irish Free State, in the aftermath of their abject failure to achieve this in Britain.

Maxton and McGovern seek a visa for Trotsky from de Valera

Trotsky briefly gained permission in mid-1933 to reside in France thanks to the efforts of dedicated French supporters such as Maurice Parijanine. However, by early 1934 the alignment of the French and Soviet governments foreshadowed impending trouble for Trotsky who once described himself as living ‘on a planet without a visa.’[32]

Perceiving parallels between the turbulent politics of France at this time and Russia prior to the October Revolution in 1917, the former Bolshevik leader privately voiced such incendiary opinions and advised comrades on political strategy.[33]

This was sufficient enough reason for the French government to claim Trotsky had reneged on his promise not to interfere in French domestic affairs. In April 1934, his visa was revoked by the Minister of the Interior, Albert Surraut, and an expulsion order was signed.[34]

Reacting to the news of Trotsky’s expulsion from France, his British supporters tried again on Trotsky’s behalf to secure his sanctuary in the United Kingdom. The new home secretary, Sir John Gilmour, a Conservative serving in Ramsay MacDonald’s National Government (which was formed in October 1931 to deal with the effects of the Great Depression) announced in parliament on 3 May that ‘it has been decided not to accede to his request.’

An embittered McGovern demanded to know ‘why so many Nazi revolutionaries are allowed to enter this country, and why Trotsky is excluded?’ His question went unanswered as the Speaker interrupted: ‘This [debate] deals with only one man.’[35]

Realising that their quest to secure a visa for Trotsky from the British government had failed, Maxton and McGovern instead sought to secure residence for Trotsky in the neighbouring Irish Free State.[36]

Hoping the government of their ‘friend’ Éamon de Valera would be more amenable than Cosgrave had been with O’Brien (or MacDonald had been with them), the two Clydesiders (Maxton and McGovern) resolved to ‘approach Mr. de Valera to request permission for Trotsky to live in the Irish Free State.’[37] This was reported in the press. The Daily Mail’s political correspondent observed:

‘Trotsky would be by no means a favoured person in a Catholic country like the Irish Free State, and Mr. de Valera, with his strong personal opposition to any form of Communism, may turn the application down out of hand. On the other hand, the fact that the Irish Free State is intensely proud of its sovereignty, may be a determining factor in the decision to take a different view from the British Government.’[38]

On 2 May, the Evening Herald reported that no representations had yet been received by the Irish government on behalf of the ‘former “Red” Leader’ for permission ‘to enter the Free State and settle down in the South of Ireland.’ The newspaper speculated that ‘if an application is made’ it would be ‘inconceivable that the Government would allow the presence of a Communist leader exiled from his own country.’

De Valera was a pious Catholic and in truth, no radical. His government rejected the proposal to grant Trotsky asylum out of hand.

This view was ‘confirmed in Government circles.’ The government’s inevitable rejection centred on the claim ‘that the Free State is a Catholic country, whose whole tradition is opposed to any form of Communism… on religious grounds alone the application could not be sympathetically considered’. A source ‘closely in touch with members of the Government’ confirmed that ‘even with the most rigorous conditions against [his] taking part in any form of political propaganda’, Trotsky still would not be permitted to enter Ireland.[39]

De Valera received the Clydesiders’ request, which was addressed to him privately, in late April.[40] Rumour of the sensational application had been reported in the press in early May.

Despite Maxton and McGovern’s hope that de Valera might be persuaded to accept the refugee as a diplomatic snub against Britain (given the two countries were embroiled in the midst of a trade war), the canny de Valera realised that giving sanctuary to Trotsky would be deeply unpopular with the Irish public whilst also running contrary his own sincerely held anti-communist beliefs and Catholic faith. As such, the Executive Council announced, ‘it was quite impossible to accede to the request.’[41]

The Director of the Government Information Bureau wasted little time in denying the government were considering the request, publicly issuing their rejection on 2 May.[42] Dismayed that de Valera had poured cold water on their hopes of the Irish Free State harbouring Trotsky, Maxton and McGovern realised their goal had failed miserably in both Britain and Ireland. The Clydesiders had badly misread the Fianna Fáil government, whose supposed ‘radicalism’ was tamed by a Catholic-infused hostility to communism.

Despite the government’s politically sagacious decision to publicly reject Trotsky’s application, for the Fine Gael opposition led by Eoin O’Duffy the issue was like a red rag to a bull. On 8 May in the Dáil, Frank MacDermot, Fine Gael TD from Roscommon, asked ‘whether [de Valera] will publish to the Dáil the correspondence between certain British Socialists and himself on the subject of giving asylum to Leon Trotsky.’

Answering for the government, Seán T. O’Kelly matter-of-factly replied that such a letter had indeed been received and that the request was rejected, noting ‘it is not the custom to publish letters addressed to the President by individuals.’ O’Kelly confirmed the letter ‘was received from Mr. John McGovern, M.P. and was written on behalf of Mr. Maxton and himself.’[43]

MacDermot’s further query as to what these two British socialists found about Ireland during their January visit which led them to believe the Free State was ‘a congenial refuge for Mr. Trotsky’ was not answered.[44] The exchange was widely reported in the press.

MacDermot’s subtle implication that Fianna Fáil harboured leftist tendencies was more bombastically expressed by the Fine Gael senator John MacLoughlin on 30 May. During a debate on the issue of Fianna Fáil’s plan to abolish the Senate, MacLoughlin expressed the view that de Valera sought ‘the power to put his opponents in jail and assist him in bolshevising the country.’ Notably, he invoked Maxton to illustrate de Valera’s alleged ‘Bolshevik’ tendencies:

‘Our once prosperous farmers are now being treated as the kulaks were in Russia, and the progress to State socialism is developing with a rapidity sufficient… to satisfy Mr. Maxton, the Clydesider, who, after coming across to see the President last January, announced… that President de Valera’s ideas of Socialism were good enough for him.’[45]

Such anti-communist hyperbole was a shibboleth of Fine Gael’s political rhetoric. By linking de Valera with Maxton, the Opposition continued to push a ‘red scare’ against the government. Maxton was also a vocal supporter of the Spanish Republicans, then a deeply unpopular cause in Ireland.[46] However, the swiftness of de Valera’s public rejection of Trotsky’s asylum application left Fine Gael unable to fully capitalise on that particular issue politically.

Conclusion

The rejection of Trotsky’s application by the Fianna Fáil government spelled the decisive end of the Clydesiders’ hopes of securing a visa for Trotsky in either Britain or Ireland. In June 1936, Ellen Wilkinson MP criticised the National Government, then headed by Stanley Baldwin, for granting permits to ‘Germans known to be supporters of the [Nazi] regime’. In the same debate, the Liberal MP Robert Bernays asked whether it was not a fact that ‘the Labour Party… refused admission to Trotsky?’[47]

However, Trotskyist sympathisers such as Wilkinson confined their parliamentary activities to criticising the government for apparent double standards, rather than attempting another hopeless asylum case.

Following his expulsion from France, Trotsky briefly relocated to Norway until he received an offer of asylum in late 1936 from the Mexican government led by President Lázaro Cárdenas whose policy was to provide refuge to European leftists and Republican refugees from the Spanish Civil War.

In January 1937, Trotsky arrived in Mexico and lived with the renowned left-wing muralist Diego Rivera and his wife the artist Frida Kahlo (with whom Trotsky had an affair).[48] Trotsky was assassinated on 21 August 1940 at the desk of his Mexican study by the Stalinist agent Ramón Mercader.

Trotsky was assassinated in Mexico on Stalin’s orders in 1940s but remained a potent symbol for those sections of the far left seeking a socialist alternative to the USSR and capitalism.

In Ireland, Trotskyism has been an influential current of thought on the Irish left. In 1935, a Trotskyist supporter wrote to his leader to inform him of a meeting held with Nora Connolly O’Brien, daughter of James Connolly, where she expressed interest in the Trotskyist movement. The writer also reported to Trotsky on the (much exaggerated) strength of the Irish Citizen Army.[49]

Meanwhile, Paddy Trench from Galway was regarded as ‘first person who actively supported the Trotskyist movement in Ireland’. Trench emigrated to London where he joined the ILP in 1929, later he fought in the Spanish Civil War, and subsequently returned to Ireland where he joined the Labour Party and wrote for The Torch.[50]

Even after Trotsky’s exile and subsequent murder on the orders of Stalin, many on the Irish and international left were sympathetic to Trotskyism in the hope that he represented a democratic socialist alternative to both Stalinist totalitarianism and the capitalist West.

References

[1] Cork Examiner, 20 Jan 1925.

[2] John Horgan, ‘The great war correspondent: Francis McCullagh, 1874-1956’, Irish Historical Studies, Vol. 36, No. 44, (Nov. 2009), p. 556.

[3] Robert Service, Trotsky: A Biography, (London: Macmillan, 2009), p. 379.

[4] Ibid, p. 393.

[5] Irish Independent, 20 Feb 1929.

[6] Belfast Newsletter, 13 Apr 1929.

[7] Arthur Mitchell, ‘William O’Brien, 1881-1968, and the Irish Labour Movement’, An Irish Quarterly Review, Vol. 60, No. 239/240, (Autumn/Winter 1971), p. 326.

[8] Sligo Champion, 1 Mar 1930.

[9] Mitchell, ‘William O’Brien 1881-1968 and the Irish Labour Movement’, pp. 324-6.

[10] The Irish Worker, 2 Jan 1932.

[11] Emmet Larkin, James Larkin: Irish Labour Leader 1876-1947, (Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press, 1965), p. 297.

[12] ‘Admission of Aliens: case of Leon Trotsky’, National Archives of Ireland, (Department of the Taoiseach, Aug 1930-Sep 1930), (TSCH/3/S2430).

[13] Dermot Keogh, Jews in Twentieth-century Ireland: Refugees, Anti-Semitism and the Holocaust, (Cork: Cork University Press, 1998), pp. 150-8.

[14] The Liberator (Tralee), 10 Apr 1937.

[15] Meeting of the Cabinet, 23 Jul 1929, The National Archives, (Kew, London), (CAB 23/64/1).

[16] Belfast Newsletter, 17 Jun 1929.

[17] Meeting of the Cabinet, 26 Jun 1929, The National Archives, (Kew, London), (CAB 23/61/3).

[18] Memorandum by the Home Secretary, 9 Jul 1929, The National Archives, (Kew, London), (CAB 24/204/45).

[19] Memorandum by the Home Secretary, 24 Aug 1929, The National Archives (Kew, London), (CAB 24/204/13).

[20] Ibid.

[21] House of Commons parliamentary debate, 18 Jul 1929.

[22] Gordon Brown, Maxton, (Glasgow: William Collins Sons & Co. Ltd, 1986), p. 222.

[23] House of Commons parliamentary debate, 20 April 1931.

[24] Leon Trotsky, The Revolution Betrayed: What Is the Soviet Union and Where Is It Going?, (trans. Max Eastman), (London: Faber and Faber, 1937), p. 287

[25] James NcNaney, ‘’The Shadow of the Gunman’ in 1932 and 2020’, History Ireland, Vol. 28, No. 3, (May/June 2020), p. 41.

[26] Cork Examiner, 29 Dec 1933.

[27] Irish Press, 22 Jan 1934.

[28] Ibid.

[29] Belfast Newsletter, 17 Jan 1934.

[30] Evening Herald, 24 Jan 1934.

[31] John McNair, James Maxton: The Beloved Rebel, (London: George Allen & Unwin Ltd, 1955), p. 241.

[32] Leon Trotsky, Trotsky’s Diary in Exile 1935, (trans. Elena Zarudnaya), (London: Faber and Faber, 1958), p. 15

[33] Service, Trotsky: A biography, pp. 420-5.

[34] Trotsky, Trotsky’s Diary in Exile 1935, p. 15.

[35] House of Commons parliamentary debate, 3 May 1934.

[36] Irish Press, 3 May 1934.

[37] Cork Examiner, 2 May 1934.

[38] Ibid.

[39] Evening Herald, 2 May 1934.

[40] Irish Press, 3 May 1934.

[41] The Times (London), 3 May 1934.

[42] Irish Press, 3 May 1934.

[43] Dáil Éireann parliamentary debate, 8 May 1934.

[44] The Liberator (Tralee), 8 May 1934.

[45] Seanad Éireann parliamentary debate, 30 May 1934.

[46] Irish Press, 8 Oct 1934.

[47] House of Commons parliamentary debate, 22 June 1936.

[48] Service, Trotsky, pp. 427-436.

[49] K. Johnstone, ‘Report to Trotsky Regarding the Prospects in Ireland’, 13 Dec 1935, (https://www.marxists.org/history/etol/document/ireland-fi/johnstone.htm), (Accessed: 1 Sep 2021).

[50] Ciaran Crossey & James Monaghan, ‘The Origins of Trotskyism in Ireland’, Revolutionary History, (London: Socialist Platform Ltd., 1996), pp. 6-9.