‘The Black and Tans in Palestine’ – Irish connections to the Palestine Police 1922-1948

By Seán William Gannon

On the 30 April 1922, 760 recently disbanded members of the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) and its Auxiliary Division (ADRIC) disembarked at Haifa in Palestine.

They arrived there as the British Section of the Palestine Gendarmerie, a strike force and riot squad recruited at the instigation of the secretary of state for the colonies, Winston Churchill.

This British Gendarmerie was the start of a strong association between Ireland and the police of the British Mandate of Palestine that would last until the British withdrew in 1948.

Many members of the Royal Irish Constabulary, disbanded in 1922, ended up in the British Palestine Police force.

The British Mandate for Palestine

Britain conquered much of the Arab Middle East from the Ottoman Empire during the course of the First World War.

This included Palestine and Mesopotamia (modern Iraq), over which it was subsequently granted control under the League of Nations’ Mandate system. This gave Britain legal commissions to administer both territories with a view to preparing their populations for eventual self-government.

Britain’s assumption of these mandates was largely driven by imperial self-interest. It believed that control of Mesopotamia and Palestine would provide it a territorial buffer zone protecting imperial strategic and commercial interests (such as the Suez Canal and the land route to India) from feared Russian regional expansion.

The British mandate for Palestine incorporated virtually unchanged the Balfour Declaration of November 1917. This obligated Britain to facilitate the establishment there of a ‘national home’ for Zionist Jews, who had been settling in Palestine since the late nineteenth century. Local Arab opposition to this settlement had intensified during the Great War and, by the time hostilities in Palestine ended with the Armistice of Mudros in October 1918, it was clear that Arab anti-Zionism, despite the tendency of Zionist leaders to dismiss it as contrived, was real and deep-rooted.

Policing Palestine and the British Gendarmerie

The British Gendarmerie was intended to alleviate certain problems posed by Palestine’s army garrison after the Great War, most significantly, its expense.

Military expenditure became a serious concern in the immediate postwar period when economic realities dictated a policy of general retrenchment, this despite the fact that the empire’s territorial extent had increased.

Thus, Palestine and Mesopotamia had to be garrisoned by a British Army already thinly stretched across India, Ireland, and Egypt where concurrent upsurges in nationalist political agitation posed a cumulative challenge to the empire’s stability.

As each of these countries was deemed of critical strategic imperial importance, it was to the new mandates that Churchill turned when seeking to cut the cost of defence.

Britain had few troops to spare to police the restive Mandate of Palestine, split between Arabs and Jewish settlers.

Cost cutting was to be primarily achieved through a reduction in troop numbers by two-thirds. However, in Palestine this was problematical, as by 1921, Arab opposition to Jewish settlement was assuming the form of an inchoate nationalist insurgency.

And while the maintenance of public order was officially the preserve of the (British officered) locally recruited Palestine Police Force, its overwhelmingly Arab make-up led to partisan policing which rendered it unsuited to the task.

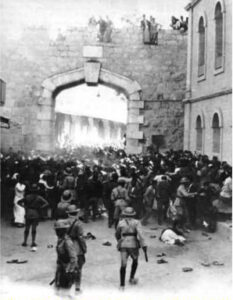

The scale of this problem became evident during anti-Zionist rioting in April 1920 and May 1921 when Arab policemen deployed to restore order began themselves attacking Jews, leaving the chief of police with little choice but to withdraw, disarm and confine them to barracks. In consequence, it increasingly fell to the British Army garrison to keep order in Palestine, meaning that a non-partisan replacement force had to be found before it could be reduced or removed.

The Palestine Police gendarmerie was recruited to bolster the locally recruited Palestine Police.

This issue preoccupied Churchill throughout the summer of 1921. Initially he proposed the establishment of another British-officered locally recruited force but soon began thinking in terms of a purely British unit rather than one that was merely British led.

His change in thinking was facilitated by developments in Ireland where the July 1921 truce between the IRA and Crown forces raised the possibility of the disbandment of the ADRIC. Churchill hit on the idea of forming, in the event of an Irish settlement, a gendarmerie for Palestine from disbanded members and approaches to the Irish ‘police advisor’, Major-General Henry Tudor, were enthusiastically received.

Thus, in November 1921, Churchill brought before the British Cabinet proposals for the recruitment from RIC sources of ‘a Palestine gendarmerie aggregating about 700 men’. Despite the staunch opposition of the chief of the imperial general staff, Sir Henry Wilson, who feared the consequences of deploying in Palestine men he privately denounced as ‘a gang of murderers’, the Cabinet approved these proposals on 21 December and formally charged Tudor with raising the force.

Recruitment from the RIC

Recruitment for the British Gendarmerie’s non-commissioned ranks opened in late January 1922. The recruitment of the commissioned ranks began in mid-February with the appointment as force commandant of Col. Angus McNeill, a Boer War and Great War veteran who knew Palestine well.

The recruitment of all ranks was completed by the first week of April and the force was assembled at Fort Tregantle, an old army encampment at Devonport near Cornwall, in preparation for its transport to Palestine.

As intended, the overwhelming majority of recruits was drawn from disbanded members of the RIC: 96 percent of the force’s 720-strong rank-and-file was ex-RIC, as was 83 percent of its 42-strong officer class. In excess of 85 percent of these men were former Black and Tans or Auxiliaries.

Over 95 per cent of the gendarmerie was initially recruited from the RIC, including former Black and Tans and Auxiliaries. Over a third were Irish.

Irishmen accounted for 38 percent of the British Gendarmerie’s 1922 draft. They also accounted for 33 percent of its complement of Black and Tans, considerably higher than the percentage of Irishmen in the Black and Tans in general (about 20 percent).[1]

This over-representation underscored the significance of perhaps the primary factor driving Irish enlistment – localized intimidatory campaigns conducted mainly by anti-Treatyite IRA elements against serving and disbanded police in the post-Treaty period.

While some ex-RIC were targeted in retaliation for real or perceived personal wartime misdeeds, mere membership of the ‘Old Force’ was sufficient cause for intimidation or attack. The actual extent of the danger they faced will, at this remove, never be known.

However, the radius of threat which emanated from those attacks which did occur (over 40 of which culminated in murder) created a climate of panic amongst ex-RIC and thousands took temporary or permanent flight from Ireland.[2] For some of these men, the British Gendarmerie provided an immediate and convenient escape route.

‘The Black and Tans in Palestine’

The re-employment of disbanded RIC personnel as policemen was a deeply controversial issue in 1922, when reports of Black and Tannery in Ireland were still fresh in the public mind. The Black and Tans and Auxiliaries had been widely associated with reprisal killings, destruction of property, and general indiscipline.

Thus, the police forces of Great Britain and the Dominions displayed a marked disinclination to accept applications from them, fearing the consequences of large-scale recruitment from the discredited force.

Initially Palestine’s high commissioner wanted to cover up the fact that ex Black and Tans were being recruited.

A scheme to transfer large numbers of Black and Tans to police another colonial theatre was also contrary to the public mood, and British officials soon raised concerns that the new British Gendarmerie would be stigmatized in consequence. Most anxious was Palestine’s high commissioner, Sir Herbert Samuel, who told Churchill that, while he had no objection to the recruitment of ex-RIC into the force provided that the men selected were of good character, it would be:

Most desirable, if it could be avoided, that no public announcement should be made connecting the Black and Tans with our Gendarmerie. Their reputation, as a Corps, has not been savoury and if any idea was created in the public mind in England or here that the Black and Tans, or any part of them, were being transferred as a body to Palestine, the new Gendarmerie might be discredited from the outset.[3]

Churchill, for whom the importance of controlling perceptions of conflict had been reinforced by the recent public relations disaster in Ireland, assured Samuel that, although recruits would be largely drawn from amongst disbanded Black and Tans and Auxiliaries, this would be given as little prominence as possible.

To this end, he directed an extraordinary charade designed to obscure the extent to which the British Gendarmerie was to be recruited from RIC sources, instructing Tudor to conduct recruitment ‘with a view to eliminating as far as possible the moral connection between the new force and the [Black and Tans and the ADRIC], thereby disposing of the inevitable idea that we are importing into Palestine the traditions of recent Irish politics’.[4]

Given the scale of its recruitment from RIC sources, this unsurprisingly failed, and the British Gendarmerie quickly came to be defined by its cohort of Black and Tans. Its ‘Black and Tan’ character was underscored by Churchill’s appointment of Henry Tudor himself to overall command. He assumed the dual role of Palestine’s general officer commanding and Inspector-General of Police and Prisons’ on 15 June 1922.

The Colonial Office was distinctly unimpressed by the British Gendarmerie’s Black and Tan label which it indignantly dismissed as ‘a convenient way of describing the force for controversial purposes’.[5]

But in Palestine, where incidents of police brutality in revolutionary Ireland had been widely reported in the press, elements of the civil administration calculatedly exploited its reputation for deterrent effect and, by the time the force docked in Haifa, propaganda against it was already widespread.

Their success in this was noted by Douglas Duff, a former Black and Tan and British Gendarmerie constable who subsequently forged a career as an author: he reported being asked by a ‘trembling’ Arab brothel-keeper on his arrival whether he belonged to ‘the new Police which she had heard had been sent to Palestine because of the murders we had committed in some land from which the English had been driven because of our brutalities’.[6]

In Palestine

The British Gendarmerie’s prior reputation, given credence by its formidable appearance, was largely sufficient to prevent breaches of Palestine’s peace.

In early July 1922, for example, it maintained public order during a two-day strike in Jerusalem by the intimidatory power of its presence alone and this was similarly sufficient to do so during the official proclamation of the British Mandate two weeks later.

On the rare occasions when the British Gendarmerie was actually required to get physical, its policing was certainly robust: its favoured method of dispersing riotous assemblies was to charge the crowd and beat it back with rifle-butts and batons, while its approach to tackling brigandage was to shoot on sight and to kill.

This confirmed for the populace that the British Gendarmerie’s fearsome reputation was deserved, enhancing its deterrence in turn. Consequently, Palestine was largely peaceable during its time there.

The Gendarmerie found Palestine in 1922-1926 far more peaceful than Ireland had been.

Duff’s graphic (and largely fictionalized) accounts of British Gendarmerie indiscipline and brutality have so shaped perspectives on the force that the view that it lived up to its prior reputation in Palestine is today an historical commonplace. In actuality, it did not fulfill expectations in this regard.

There were initial problems with (mainly) alcohol-related indiscipline amongst the rankers. But, determined that what one officer termed ‘the Irish way of things’ would not prevail in Palestine, it was quickly curtailed through fines, curfews, and dismissals.[7]

Thus, by the end of 1922, force discipline was being variously described by those on the ground as ‘very good’, ‘very high’, and ‘excellent’.

That discipline was relatively good is confirmed by the dismissal rate which worked out at 2 percent annually, which compared very favourably with the rate among the Black and Tans and Auxiliaries in Ireland which Bill Lowe estimates at 4.7 percent, rising to almost 7 percent if those recorded under what he termed ‘the ambiguous category discharged’ are included. And, indeed, 8 percent of the ‘cluster sample’ analysed by David Leeson in his study of the Black and Tans and Auxiliaries was dismissed.[8]

Nor, broadly-speaking, did the British Gendarmerie adopt the tactical constants that came to define policing in revolutionary Ireland. Certainly, its use of lethal force against brigandage, which, while seldom self-consciously political had begun to develop an anti-Zionist character by 1922, reflected the strategy adopted against IRA flying columns in 1919/21.

But there was no parallel in Palestine at this time with the policy of reprisals against Republicans and their communities for attacks on the RIC. Retaliation for attacks on the gendarmes targeted the perpetrators alone and even in cases where gendarmes were killed, revenge was not wreaked on the wider community.

Violence in Palestine was largely between the Arab and Jewish communities – and not directed against the imperial rule the British Gendarmerie upheld.

That a force freshly drawn from the Black and Tans and the ADRIC (and which included officers responsible for some of the most heinous crimes of the Irish revolutionary period such as the murders of the Loughnane brothers and the ‘Scariff Martyrs’) did not behave with similar license lends support to Leeson’s thesis that historians have undervalued the importance of situational factors when analysing Ireland’s policing in 1919/21.

In his view, the brutality that the RIC and Auxiliaries frequently displayed mainly derived from the challenges of the situation into which they were thrust – a vicious guerrilla insurgency against which they formed an inadequate frontline.

But these men operated in a very different environment during their time with the British Gendarmerie. Despite the persistence of Arab-Jewish tensions, Palestine was largely peaceable during their four years of service (not least on account of their presence) and they spent most of their time at base marking time between the occasional emergencies requiring their deployment.

As one Colonial Office official colourfully put it, ‘McNeill and his men spend much of their time waiting expectantly for the veil of the Temple to be rent in twain, while in the meantime doing nothing in particular’.[9] Furthermore, they were utterly unchallenged by these emergencies, their capacity to quell them never in doubt.

Nor, unlike in Ireland, were they primary target of what violence occurred. In Palestine it was inter or intra-communal – between or within the Arab and Jewish communities – and not directed against the imperial rule the British Gendarmerie upheld. Hence, the stresses and strains of the Irish situation were absent in Palestine to the point that Tudor described the country as ‘a rest cure after Ireland’.[10]

The British administration was not directly targeted by anti-Zionist demonstrators until 1933 and its security was unchallenged until the Great Arab Revolt of 1936-1939, when a significant swathe of Arab society rose up against the government and its Jewish immigration policy.

That the British Gendarmerie would have behaved in a very different way had it found itself the focus of an IRA-style insurgency was indicated by McNeill’s recommendations for tackling the Arab Revolt: then retired outside Acre, he told BSPP friends that they ‘should try to spread terror in the land … you would only have to be really brutal and bloodthirsty for about a month and [the Arabs] would be eating out of your hand’.[11]

The Irish in the ‘British Section’ of the Palestine Police 1926-1948

The British Gendarmerie was a victim of its own success in maintaining public order in the Palestine Mandate: it was disbanded in April 1926 following a reorganisation of the garrison in light of the improved security situation.

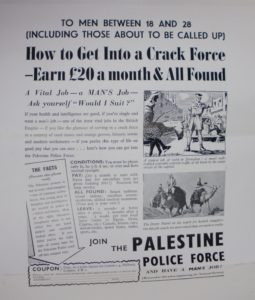

It was replaced by a new ‘British Section’ attached to the Palestine Police (BSPP), a 220-strong crack squad intended to stiffen the main locally recruited body of the force. Just under 100 of its original draft were former gendarmes, 72 of these ex-RIC.

However, its strength was dramatically increased in response to emergent threats to public security, trebled in the wake of anti-Zionist riots in 1929 and gradually increased to 2,800 during the Arab Revolt, when anti-Zionist resistance escalated into large-scale insurgency.

Though most ex RIC men left the force in 1926, Irish recruitment to the Palestine police remained strong.

Force strength was further increased to over 4,000 between 1946 and 1947 to meet the challenges of the intensifying Zionist insurgency. This was waged by Lehi, Haganah, and the Irgun Zvai Leumi variously, or in concert, since summer 1939 to force a British withdrawal from Palestine and set up an independent Jewish state there. By the time the Mandate ended in April 1948, somewhere in the region of 10,600 men had served in the BSPP.

A handful of the British officers in the original Palestine Police was Irish, most notably Captain Eugene Quigley from Sligo, who went on to have a very high-profile career in the force, and Captain James Mackenzie from Belfast, who drowned in April 1922 trying to save the life of an Arab colleague who had been thrown from his horse into the Jordan River.

But significant Irish enlistment in the Palestine Police did not begin until the raising of the BSPP. Nineteen Irish members of the disbanding British Gendarmerie transferred to the force in April 1926, accounting for 10 percent of its original strength, and small numbers of Irishmen were included in the batches of new recruits dispatched from London prior to the 1929 riots.

Enlistments increased in its wake and sharply increased during the years of the Arab Revolt – approximately 11 percent of all new recruits was Irish – so that, by June 1939, the retired Calcutta Police commissioner and imperial ‘counter-terrorism’ expert, Sir Charles Tegart, who had been drafted in as ‘advisor’ to the Palestine Police in October 1937, could remark that the force was then ‘flavoured with a strong seasoning of Irishmen of the right kind’.[12] (Tegart was himself Irish, the Derry-born son of a Church of Ireland clergyman who grew up in Dunboyne, county Meath).

Irish enlistments declined during the Second World War, and by December 1945 the percentage of Irishmen in the force stood at 8 percent. However, the postwar years saw a sharp rise in recruitment from Ireland in response to an intensive recruitment drive by the Crown Agents for the Colonies which targeted Ireland: 15 percent of those recruited in 1946 were Irish as were 19 percent of those recruited in 1947.

This influx of Irishmen was observed by those on the ground. In July of that year, a visitor to Ireland from Palestine with ‘an intimate knowledge’ of the BSPP told the Irish Times that ‘he had rarely visited a police station in Palestine where he did not find an Irish member’.[13]

Irish visitors to Palestine also noted the presence of large numbers of Irish police, as did Irish BSPP recruits themselves.

For example, a Jerusalem-based Irish photographer reported meeting several compatriots serving in the force: ‘You meet them here from all over Ireland – the Palestine Police Force is full of them’.[14] Within the confluence of contributory factors that influenced each individual decision to enlist, a signal motivation is generally discernible, chief amongst them economics, endo-recruitment, and the quest for less ordinary lives.

Shortly after his arrival in Palestine, Tudor sourly remarked to the attorney-general, Norman Bentwich, that his gendarmes ‘had to leave Ireland because of the principle of Irish self-determination and were sent to Palestine to resist the Arab attempt at self-determination’.[15]

But it was, in fact, to Irish BSPP that this task primarily fell. Like the RIC before them, those recruited in the 1920s and 1930s found themselves forming the British imperial frontline against an anticolonial insurgency, the Great Arab Revolt, which saw the emergence of Black and Tannery in the Palestine Police.

Just two months after the outbreak of this revolt in 1936, Jerusalem’s Anglican archdeacon declared himself ‘seriously troubled at the “Black and Tan” methods of the police’ and, by September 1938, even the hardline high commissioner, Sir Harold MacMichael, was deploring what he termed their ‘black-and-tan tendencies’.[16]

The BSPP’s response to the subsequent Zionist insurgency was, generally-speaking, far more restrained. However, the perceived incidence of excess during authorized counterinsurgency operations, coupled with unofficial police reprisals, was sufficient to evoke memories of Ireland, particularly in the postwar period when the BSPP-Black and Tan comparisons became so commonplace that the colonial secretary was compelled to reject them in parliament.

The frequent brutality of the BSPP’s response to the Arab and Zionist insurgencies is generally attributed to the fact that the force was descended directly from the Black and Tans via the British Gendarmerie and thereby imbued with a ‘Black and Tan ethos’. According to this view, former Black and Tans and Auxiliaries serving in the BSPP, some at very senior rank, imported from revolutionary Ireland a policing model based on brute force.

This view was in fact current at the time: writing in 1949, Arthur Koestler described the Palestine Police as ‘one of the most disreputable organisations in the British Commonwealth’, something he partly attributed to the fact that there were ‘Black and Tan veterans in leading positions’.[17]

But the evidence does not bear this out. For example, far fewer RIC veterans remained in the BSPP than has traditionally been thought (43 in the late 1930s in a force of 2,800 and just 25 in the mid-1940s when it was almost 4,000-strong), while the more drastic counterinsurgency initiatives introduced in 1936/48 were instituted by police officers with non-RIC pedigrees, or by external agents.

‘A repetition of the Irish show’

In any case, an examination of both BSPP counterinsurgencies in Palestine presents further evidence for Leeson’s thesis on the primacy of situational factors in explaining Black and Tannery.

Unsettled by the anti-Zionist violence of 1929 riots, one senior Palestine Police officer (and former ADRIC ‘C Company’ cadet) predicted ‘a repetition of the Irish show’ if Arab grievances were not assuaged and the outbreak of the Arab Revolt proved him right.

Like Dublin Castle in 1919, the Palestine government was initially reluctant to interpret the violence of 1936 as anticolonial, treating it instead as a crime wave which, as the guardians of law and order, the police were lined out to suppress.

Unsettled by the anti-Zionist 1929 riots, one senior Palestine Police officer (and former Auxiliary predicted ‘a repetition of the Irish show’ if Arab grievances were not assuaged.

This insistence that Arab violence was criminal saw the BSPP tackling an insurgency it was ill-equipped to so do other than by brutal coercion, which as in the RIC’s case, was a testament to force weakness rather than force strength. As in Ireland, the targeting by rebels of outlying police stations forced a humiliating retreat to urban centres by an ill-equipped and ill-trained constabulary and the increasing assumption of responsibility by the military for the counterinsurgency.

In Palestine, this culminated in the granting of full operational control of the police to the army in September 1938, although responsibility for the day-to-day maintenance of public security was left in police hands. The fact that the police were left to do the ‘dirty work’ such the expropriation of produce from Arab villages in lieu of collective fines, coupled with the rising police casualty rate, took a severe toll on force discipline and morale, leading to the inevitable emergence of ‘black-and-tan tendencies’.

As BSPP Constable Reubin Kitson noted, ‘it’s very difficult when you’re being attacked not to retaliate in some way and [we] did retaliate … when the so-called terrorism became critical, in order to fight terrorism, we became terrorists more or less’.[18]

Situational factors also drove the excesses of the BSPP’s response to the Zionist insurgency. Despite being even more untrained for the task than it had been in the late 1930s, the force again found itself forming the first line of imperial defence and the pressures this incurred led to occasional collapses in morale and discipline. The situation was exacerbated by anger at the rising police casualty rate.

Like the RIC, which considered the IRA’s method of ‘hit and run’ warfare to be, as the British Army’s rebellion record described it, ‘in most cases barbarous, influenced by hatred and devoid of courage’, BSPP personnel were enraged by the murder of their colleagues by (as they saw them) cowards who shirked a fair fight.[19]

In fact, ‘Zionist terrorism’ was not only repugnant to what the British (officially, at least) considered legitimate conduct during armed conflict. But it also offended a conception of imperial prestige derived from race-based ideas about the relationship of British security forces to imperial subjects, according to which the former dispensed justice to the latter and had an a priori right to a monopoly on force.

Irishmen working in the Palestine Mandate, interviewed by a visiting Irish Jesuit in 1947/48, drew comparisons with the Irish situation 20 years hence.

Recognising the pressure placed on the BSPP by the Zionist insurgency they, ‘now realised, as never before, what the strain of conflict with an underground enemy can do to human nature’ and were surprised that the police counterinsurgency was not more robust. For, while ‘not in the least condoning Black-and-Tan methods of reprisal, [they] knew how strong can be the temptation to resort to them in extremity’.[20]

Partly on account of this insurgency, the British terminated its mandate for Palestine effective from 15 May 1948. The disbandment of the BSPP commenced in January and the great majority had departed by the time the new State of Israel was declared.

Many of the Irish amongst them remained in policing. Some joined the constabularies of Britain and the Dominions, while 130 enlisted in colonial forces, primarily in Malaya (50), Africa, and Hong Kong, continuing a tradition of Irish imperial policing with its roots in the ‘Old RIC’.

Seán William Gannon is a historian of Modern Ireland, the British empire, and their intersections. His book: The Irish imperial service: policing Palestine and administering the empire, is published by Palgrave MacMillan.

References

[1] Seán William Gannon, ‘“Sure it’s only a holiday”: the Irish contingent of the British (Palestine) Gendarmerie, 1922-1926’, Australian Journal of Irish Studies, pp 64-85, at pp 66-7.

[2] Thirty members of the Ulster Special Constabulary were killed during this period as well. Figures abstracted from Richard Abbott, Police Casualties in Ireland, 1919-1922 (Cork, 2000).

[3] Churchill Papers (CHAR), CHAR/17/11, Samuel to Churchill, 11 Dec. 1921.

[4] British National Archives (TNA), Colonial Office official correspondence (CO), CO/733/15/639-40, Grindle to Tudor, 24 Dec. 1921.

[5] TNA, CO/733/35/616-7, Shuckburgh, Colonial Office minute, 20 Dec. 1922.

[6] Douglas V. Duff, Bailing with a teaspoon (London, 1953), p. 31.

[7] John Jeans, ‘The British (Palestine) Gendarmerie’, Malayan Police Magazine, 4/9 (1931), p. 257.

[8] W. J. Lowe, ‘Who Were the Black and Tans?’, History Ireland, 12/3 (2004), p. 50; The Black and Tans: British police and auxiliaries in the Irish War of Independence (Oxford, 2011), p. 69.

[9] TNA, CO/733/72/61, Roland Vernon, Colonial Office minute, 9 Aug. 1924.

[10] RAF Museum, Viscount Trenchard papers, MFC76/1/285, Tudor to Churchill, 1 Oct. 1922.

[11] CHAR/2/348, McNeill to Churchill, 20 Dec. 1937.

[12] Palestine Post, 4 June 1939.

[13] Irish Times, 1 July 1947.

[14] Connacht Tribune, 9 Aug. 1947.

[15] Norman & Helen Bentwich, Mandate memories, 1918-1948 (London, 1965), p. 87.

[16] Middle East Centre Archive Oxford, GB165-016 Jerusalem and East Mission collection (JEMC), 61/1, Stewart to Matthews, 17 June 1936.

[17] Arthur Koestler, Promise and fulfilment: Palestine 1917-1949, 2nd edition (London, 1983), p. 15.

[18] Imperial War Museum, Sound archive 10688, Reubin Kitson interview, 26 Apr. 1989.

[19] Quoted in Paul McMahon, British Spies and Irish Rebels: British Intelligence and Ireland, 1916-1945 (Woodbridge, 2008), p. 164.

[20] J. W. W. Murphy, ‘Irishmen in Palestine, 1946-1948’, Studies: An Irish Quarterly Review, 40/157 (1951), p. 88.