Ruth Russell in Revolutionary Ireland

By Mark Holan

On Jan. 17, 1920, six months after he arrived in America to promote the Irish republic, Éamon de Valera surrounded himself with supporters in the heart of New York City to announce a bond drive to raise funds for the year-old Dáil Éireann. Twelve days later, without similar fanfare, the Sinn Féin leader endorsed a new book sympathetic to the Irish cause by Chicago journalist Ruth Russell.

“I congratulate you on the rapidity with which you succeeded in understanding Irish conditions and grasped the Irish viewpoint,” de Valera wrote to Russell. “I hope we shall have more impartial investigators, such as you, who will take the trouble to see things for themselves first hand, and who will not be imposed upon by half-truths.”[1]

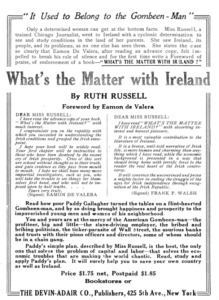

The Jan. 29, 1920, letter—on “Republic of Ireland (American Delegation)” stationary and perhaps written by an aide—appeared as front matter in Russell’s What’s the matter with Ireland?, which was based on her 1919 reporting from Ireland for the Chicago Daily News. In their Dublin meeting shortly after his escape from Lincoln Prison and before he stowed away to America, she described de Valera as a “tall, pale man, 37 years of age [who] spoke with a student’s concentration.”[2]

Ruth Russell, a young American journalist, reported from Ireland in 1919 on political and social conditions and wrote a book ‘What the Matter with Ireland?’

Russell interviewed other leading political and cultural figures of the Irish revolution, including Arthur Griffith, Maud Gonne McBride, Michael Collins, Constance Georgine Markievicz, and George William Russell (no relation).

Russell also mixed with Ireland’s poorest citizens, people in the shadows of the revolution. She lived in the Dublin slums with families crammed into one-room tenements and applied for hard-to-find jobs with other women, many caring for children and supporting unemployed husbands and brothers. “Their constant toil makes the women of Ireland something less than well-cared for slaves,”[3]Russell wrote.

She interviewed workers and labor leaders in the April 1919 Limerick soviet, at Belfast textile mills, and outside a soon to open Henry Ford-owned tractor plant. “On the edge of the sidewalks in Cork there is a human curbing of idle men,”[4] she reported.

It is debatable whether Russell remained the “impartial investigator” suggested by de Valera’s letter. In her book’s introduction, she stated that “exploitation by the world capitalist next door to her”[5] answered the question posed by the title.

She joined at least one women’s protest against British rule in Ireland, and testified favorably to the Irish republican cause before the American Commission on Conditions in Ireland. Then, as quickly as she joined the debate about the “Irish question”, Russell retreated from the issue for reasons that remain mysterious.

Editor’s Daughter

Ruth Marie Russell was born March 24, 1889, in Chicago, the eighth child of Martin J. Russell, a Chicago Times editorial writer, and his wife, Cecilia [nee Walsh].[6] Both parents were born to pre-Great Famine Irish immigrants, one of whom lived with the family through Russell’s childhood. By the late 19th century, 16 percent of Chicago’s population were native Irish.[7]

Russell attended a nearby Catholic girls academy. In 1900, at age 11, she mourned her father’s sudden death at age 54. In 1906 she enrolled at Chicago Normal College to prepare for a teaching career.[8] In 1909 she matriculated into the University of Chicago, and graduated four years later with a Bachelor of Philosophy degree.[9] In June 1914, she sailed to France to study at Grenoble, then hurried home two months later with the outbreak of the Great War.[10]

Ruth Marie Russell was born March 24, 1889, in Chicago, the eighth child of Martin J. Russell, a Chicago Times editorial writer

By 1917, Russell “decided to enter the family field” and followed her late father and an older brother, James Russell, into journalism.[11] She began working at the Daily News as a “special writer”[12], typically an ad hoc or freelance arrangement that was one of the best ways for women to enter the newsroom.[13]

For two weeks in 1918, the 5-foot, 9-inch reporter hauled heavy steel tools to shell turners inside a Chicago munitions factory for an undercover series about women in war work.[14] Such “stunt girl” journalism had first appeared more than 30 years earlier, as Elizabeth Cochran (aka Nellie Bly), Nora Marks, and other women began writing first-person accounts about oppressive conditions in workplaces, hospitals, and public institutions.

The Daily News also helped pioneer foreign news coverage, especially during the war years. The dispatches its correspondents filed from global hot spots were published in two dozen U.S. newspapers that subscribed to the service.

In January 1919, a week after Sinn Féin established the first Dáil Éireann in Dublin, a Daily News editor urged the U.S. government to expedite a passport for Russell. “Because of the news conditions in Ireland at the present time, it is hoped that she may leave as soon as possible,” News Editor Henry J. Smith wrote to U.S. Secretary of State Robert Lansing.[15] Russell arrived in Dublin two months later, on the eve of St. Patrick’s Day, a week before her 30th birthday.[16]

Her Dispatches

Russell was not the only American reporter in Ireland, which attracted scores of foreign correspondents seeking contrast to the post-war Paris peace conference.

As Maurice Walsh notes, “The Irish revolution became an international media event … The way in which visiting correspondents wrote up the Irish revolution was crucial to its outcome, both in the sense that they affected perceptions of the war and that they connected Ireland to the world.”[17]

From March through June, 1919, Russell reported from Dublin, Cork, Limerick, Belfast, and rural Dungloe in County Donegal.[18]

Her first story detailed the triumphal Dublin return of Countess Markievicz, who in December 1918 became the first woman elected to the British Parliament.

Markievicz won a Dublin constituency while incarcerated for her role in Ireland’s anti-conscription protests earlier that year. Her election and the Sinn Féin route of Irish parliamentary nationalists had received considerable press coverage in America, but Markievicz’s prison release was largely ignored by U.S. newspapers, giving Russell a scoop.

Her first story detailed the triumphal Dublin return of Countess Markievicz, who in December 1918 became the first woman elected to the British Parliament.

Russell’s story did not contrast Markievicz’s historic election win to American women still struggling for the right to vote. Instead, Russell offered a narrative, scene-setting approach to the homecoming that differed from most straight-news reporting of the day. She even placed herself in the action, close enough for Markievicz to whisper an aside:

Down one curb of the Eden quay uniformed boys with coat buttons glittering in arc lights were ranged in soldier formations. Up the other curb squads of girls were blocked. All were members of the citizens’ army of the Transport Workers union. … Up in the bare front room of the Liberty hall headquarters, where dim yellow electric bulbs were threaded from the ceiling, the countess welcomed her friends of the days of the revolution of 1916. … With her eyes slight behind her metal rimmed glasses, the countess marched to the big central window and flung it wide open to the spring night. Before she addressed the crowd below, she said to me: “Our fate all depends on your president [Woodrow Wilson] now.”[19]

Russell witnessed the Dublin arrival of the American Commission on Irish Independence, a non-U.S. government delegation of three prominent Irish Americans sent to the 1919 Paris peace conference to lobby for Ireland. She reported on a failed effort in the international race to make the first non-stop transatlantic flight. But her most poignant dispatches were about the non-newsmakers who struggled amid the chaos and poverty of the revolution.

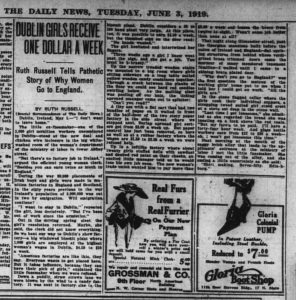

Russell described looking for work in Dublin with recently unemployed women munitions workers, like those she had labored with two years earlier in the Chicago armament plant:

Down a puddly, straw-strewn lane we were blown by the wind to a candy factory. It was next in factory size to the biscuit plant. Dublin considers a 50 to 100 hand plant very large. At this place, it was possible to earn $4.50 a week, but the thumbed sign on the door read: No hands wanted. … Up the narrow wooden treaded stairs we mounted to a big room where girls sitting sideways on a long table nailed yellow wooden candy containers together. Through a crack between the planks of the floor we could see hard red candies swirling below. As the melting sleet was pooling off our hats, the ticking aproned manager came out to sputter: Can’t you read? … That night along Gloucester Street, past the Georgian mansions built before the union of Ireland and England, flat uprising structures from behind whose verdigrised brass trimmed doors came the mummers of many membered tenement families–I walked until I came to a shining brass plated door. “Why don’t you go to England?” was the first question the matron of the working girls home put to me when I told her I could get no work. “All the girls are.”[20]

Some of Russell’s stories were published in American newspapers that subscribed to the Daily News foreign service up to two months after their Irish datelines. Her stories appeared at least through October 1919, though she returned to America in August.[21] [22]

Women pickets

In January 1920, as the Irish bond drive began and de Valera’s letter was prepared, The Ladies Home Journal published Russell’s story of finding herself “broke” in England during a two-week wait for her ship to America.[23]

Determined to pass the time as inexpensively as possible, Russell reported that she walked more than 100 of the 234 miles from London to Liverpool.

This appears contrary to the January 1919 promise her Daily News editor made to the U.S. State Department, that she “would continue to be on a salary basis”[24] while outside of America.

The Daily News archives in Chicago, including the 1919-1920 papers of the news editor who wrote to the State Department, and other top newsroom managers; does not contain any documentation of Russell’s work or relationship with the paper.[25] Likewise, de Valera’s diary and related papers from the 1919-1920 U.S. tour do not mention his March 1919 Dublin interview with Russell, or any exchanges with her in America.[26]

At the start of April 1920, Russell joined a few dozen other women at a protest in front of the British Embassy in Washington, D.C.

At the start of April 1920, Russell joined a few dozen other women at a protest in front of the British Embassy in Washington, D.C. The demonstration was organized to increase support for the Irish republic as the war there grew more brutal. Irish and Irish-American activists disagreed on the strategy, however, with opponents worried it would undermine de Valera’s mission in America.[27]

Mainstream newspapers accounts identified many of the women demonstrators, including “Miss Ruth Russell of Chicago”. The coverage did not mention her 1919 reporting from Ireland for the Daily News, which published a front-page brief about the embassy protest, but did not name any of the women.

The Irish News and Chicago Citizen, a pro-nationalist weekly, did connect Russell to the Daily News, her late father, the editor, and older brother who also worked as a journalist.[28] Its front-page story suggested the Daily News sent Russell to Ireland “with a pot of the blackest paint, with, perhaps, a big order to besmirch the character and objects of the Sinn Féiners.” The overheated, but unsourced, report continued that “…on investigation, [Russell] discovered the odious and detestable nature of the services expected of her and in disgust renounced and repudiated them.”

Russell was “among other women connected to journalism” at the protest.[29]Perhaps she participated only in the role of undercover reporter. It does not appear Russell was among the several women who were arrested, or who participated in subsequent demonstrations in the following months.

Book reviews

Extracts of Russell’s What’s the matter with Ireland? soon appeared in The Freeman[30], a monthly magazine edited by libertarian author and social critic Albert Jay Nock. The women outside the British Embassy circulated its editorial, “The Recognized Irish Republic”, a week in advance of publication.[31]

Russell’s Freeman pieces and book are similar in style and substance to her Daily News dispatches. This undercuts the Irish News’ suggestion of bias by the bigger paper, despite Russell’s book introduction complaint about “a fellow journalist propagandized into testy impatience with Ireland.”[32]

The Devin-Adair Co. of New York, which specialized in Irish titles, published the 160-page book. An advertisement[33] declared: “Only a determined woman can get at the bottom of the facts,” and that Russell “saw Ireland, its people, and its problems as no one else has seen them.”

The advert quoted de Valera’s letter and a testimonial from Frank P. Walsh, a member of the American Commission on Irish Independence, whom Russell met in Ireland.

One review stated that Russell “saw Ireland, its people, and its problems as no one else has seen them.”

In a review, the New York Tribune described the book as “a forthright presentation of the situation as it offers itself to the inquiring sojourner, given in the journalist’s terms of first-hand observation and current statistics.” It also found: “Not the least interesting actors in the Irish drama are the women leaders of the revolutionary party.”[34]

The Catholic World was tougher on Russell: “She succeeds in rousing our sympathy for the poor working girls of Dublin, and other unfortunate people of the city and the bog-field. But when she takes up the political she seems unable to do justice to her subject. … There is no doubt Miss Russell’s intentions are good, but it is doubtful if such books as this will help Ireland’s cause.”[35]

Commission testimony

Ireland’s cause soon became the focus of a more headline-grabbing effort. Oswald Garrison Villard, editor of The Nation magazine, invited U.S. senators, state governors, big city mayors, college presidents and professors, religious leaders, newspaper editors, and other prominent citizens to establish a “Committee of One Hundred” to form and oversee an eight-member commission known as the American Commission on Conditions in Ireland.[36]

The commission held six hearings from November 1920 through January 1921, with 18 witnesses from Ireland; two from England (others were invited, but declined); and 18 Americans.

Russell testified in front of the American Commission on Conditions in Ireland in 1920. She argued that revolt in Ireland was impelled by ‘economic conditions’.

The opening session came three weeks after the hunger-strike death of Irish nationalist and Cork Mayor Terance MacSwiney generated international headlines, among the many developments that now dated Russell’s spring 1919 reporting. MacSwiney’s widow and sister testified to the commission in early December; Russell appeared a week later, on Dec. 15, at the Lafayette Hotel in Washington, D.C.[37]

She fawned about the Irish republican leaders she had met more than a year earlier.

“They were extremely cool-headed and intelligent,” Russell testified. “The crowd of Sinn Féin leaders … were, I think, the most brilliant crowd of people that I have met in my life, and as a newspaper person I have mixed in at a good many gatherings.”[38]

In Russell’s opinion “it would have been impossible for these brilliant young leaders to rally the forces in Ireland behind them unless the people were driven to revolt by the economic conditions that are pressing into them.” She blamed Protestant politicians in Ulster, who “work on the religious prejudices of the people, so that the rich mill owners profit by the division of the people, especially the laboring people.”[39]

For more than two hours,[40] Russell answered the commission’s questions about political, economic, social, educational, and religious conditions. Near the end of the session she was asked how conditions in Ireland compared to the streets of New York, Chicago, and other American cities.

“I felt perfectly safe,” Russell replied. “I walked from the telegraph office in Limerick at two o’clock in the morning through perfectly black streets to my hotel. I inquired the direction several times, and was finally assisted to my hotel by a member of the Black Watch (an ancient form of civilian night guard). But there was no interference with my progress at all.”[41]

Associated Press wire service coverage of Russell’s testimony, repeated in dozens of newspapers across the country, identified her 1919 Irish reporting trip for the Daily News.[42] The AP report did not link Russell to the April 1920 demonstrations at the British Embassy, which was absent in her testimony. The Daily News did not report that day’s commission hearing.

Coverage of Russell’s commission testimony appeared two weeks later in Irish newspapers, which focused more on the testimony of Sinn Féin’s Laurence Ginnell. The Evening Herald of Dublin reported that Russell “gave a terrible picture of poverty in Ireland, and on sweating in mills and factories in the North of Ireland.”[43]

Russell was quoted only once in the 152-page interim report the commission released in spring 1921. She was mentioned in some U.S. press coverage of the report, which British officials dismissed as biased toward the revolutionaries.

Teacher & novelist

In 1921, Russell reverted to her earlier training and began working as a Chicago public high school English teacher and student newspaper adviser.[44] A decade later, she published Lake Front, a novel of Chicago’s first 100 years told through three generations of the O’Mara family.

The book nods to 19th century Irish nationalism through a character called “the Fenian,” an immigrant veteran of the 1848 Young Irelander Rebellion. “Irishmen must no longer be subject but free, and they must have the chance to be free in their own republic,” he says. “I will hold that every Irishman’s first duty is to Ireland.”[45]

In 1921 Russell left journalism and became high school English teacher. She later wrote a novel about an Irish American family in Chicago.

Beyond her reporting and commission testimony, I have not located any diaries, letters, or interviews with Russell that illuminate her private thoughts about the 1919 reporting trip or 1920 advocacy. “I was sent as a correspondent to Ireland and wrote a book about it,” she said in a newspaper interview to promote the novel.[46] She returned to Ireland on European travel with her younger sister, Cecilia, also a teacher.[47]

Russell, who never married, died on Nov. 28, 1963, age 74, of heart disease, in a Chicago convalescent home.[48] News about the assassination and burial of John F. Kennedy, the first Irish-American and Catholic U.S. president, dominated the last week of her life. Irish President Éamon de Valera, then 81, returned to America for Kennedy’s funeral, 44 years after being interviewed by Russell in Dublin and providing the January 1920 letter for What’s the matter with Ireland?

See Mark Holan’s blog series American Reporting of Irish Independence, which includes a more extended look at Ruth Russell. He can be reached at [email protected].

© 2020 by Mark Holan

References

[1] Ruth Russell, What’s the matter with Ireland? (New York: Devin-Adain, 1920), p. 9-10.

[2] “De Valera Hides in Dublin, Crowds Wait” Chicago Daily News, March 29, 1919.

[3] Russell, Ireland?, p. 22.

[4] “New Irish Factory Has American Ideas,” Omaha (Nebraska) World Herald, July 6, 1919.

[5] Russell, Ireland?, p. 13.

[6] Hyde Park, Illinois, City Directory, 1889, accessed via Ancestry.com, U.S. City Directories, 1822–1995; 1900 U.S. Federal Census: Chicago Ward 32, Cook, Illinois, 12; Enumeration District: 1035; FHL microfilm: 1240287; accessed via Ancestry.com; Baptismal record with address and mother’s maiden name accessed accessed via FindMyPast.com; “Chicago’s First One Hundred Years Penned and Illustrated by Ruth Russell and Ruth Kellogg,” Hyde Park Herald , Sept. 18, 1931.

[7] Michael F. Funchion, Chicago Irish Nationalists (Arno Press: New York, 1976) p. 9, citing 1890 U.S. Census.

[8] Ruth Russell’s Chicago Public Schools (CPS) employment record obtained March 20, 2019, via author’s Freedom of Information Act request. CPS redacted large portions of the record. Author appealed to the Public Access Counselor, Illinois Attorney General, for review, and subsequently prevailed in having the full record released.

[9] Ruth Russell’s University of Chicago transcript obtained April 10, 2019, from Special Collections Research Center, University of Chicago Library.

[10] “Certificate of Registration of American Citizen” letter dated Sept. 1, 1914, shows Russell left Chicago on June 28, 1914, and arrived at Grenoble, France, on July 16, 1914. “Ellis Island and Other New York Passenger Lists, 1820–1957” shows Russell left France Aug. 22, 1914, and arrived in New York on Aug. 30, 1914. Both via MyHerage.com.

[11] “Staff Changes”, The Fourth Estate, Oct. 6, 1917, p. 29.

[12] “Purely Personal” The Fourth Estate, Nov. 23, 1918, p. 13.

[13] Carolyn M. Edy, The Woman War Correspondent, The U.S. Military, and The Press 1846-1947 (Lexington Books: New York, 2017), p. 17-18, citing Edwin Llewellyn Shuman, Steps Into Journalism: Helps and Hints for Young Writers (Evanston Press Co.: Evanston, Ill., 1894.), p. 149.

[14] Height: Ruth Russell’s Jan. 27, 1919, passport application. National Archives and Records Administration (NARA); Washington D.C.; Roll #: 699; Volume #: Roll 0699 – Certificates: 63000–63249, Accessed via Ancestry.com. U.S. Passport Applications, 1795–1925. Assignment: “Purely Personal” Fourth Estate, Nov. 23, 1918, p. 13, and “Women’s Task Too Heavy. Experience in Chicago Munitions Factory Recorded”, Morning Oregonian, Jan. 2, 1919.

[15] Smith to Lansing, Jan. 27, 1919, in Russell’s passport application.

[16] Arrival date: Evidence on Conditions in Ireland: The Complete Testimony, Affidavits and Exhibits Presented before The American Commission on Conditions in Ireland, Transcribed and Annotated by Albert Coyle, Official Reporter to the Commission. Session One, Dec. 15, 1920, p. 429.

[17] Maurice Walsh, The News From Ireland: Foreign Correspondents and the Irish Revolution (Palgrave Macmillan, New York, 2008), pgs. 3,5.

[18] Evidence on Conditions in Ireland, p. 429.

[19] “Sinn Féiners’ Woman Leader Urges Soviet”, Chicago Daily News, March 18, 1919. Edited by author.

[20] “Dublin Girls Receive One Dollar A Week”, Chicago Daily News, June 3, 1919. Edited by author.

[21] Russell departed Liverpool Aug. 1, 1919, aboard the S. S. Lapland and arrived in New York on Aug. 11, 1919, based on Ellis Island and Other New York Passenger Lists, 1820–1957. Accessed via MyHeritage.com. Coincidentally, de Valera had stowed away to America aboard the Lapland in June.

[22] The author reviewed the digital archives of Newspapers.com; Library of Congress “Chronicling America”; and smaller newspaper databases, plus the Chicago Daily News microfilm archives at the Library of Congress.

[23] “A Tramp Across England: From London to Liverpool for $32.76”, Ladies Home Journal, January 1920, 48.

[24] Smith to Lansing in Russell’s passport application.

[25] Field Enterprise Records, 1858–2007; Chicago Daily News, 1882–2007; Administrations and Operations, 1891–1978, Newberry Library, Chicago. Author reviewed multiple boxes and files March 15 and April 26, 2019, plus correspondence with library staff.

[26] Papers of Éamon de Valera (1882–1975) held at University College Dublin, Ireland. Author engaged John Dorney, editor of The Irish Story, to review targeted portions of this archive, including: 4. De Valera Biographical Material, I. Chronologies, 1916–27, and II. Diaries, 1916–61; 14. Mission to the United States, 1919–20, IV. Correspondence with members of the public; VII. Diaries and accounts of the tour; and VIII. Progress of the tour a. Planning and itineraries, b. Tours, June 1919–October 1920; and 15. Harry Boland’s Activities in the U. S., 1919–22.

[27] “American Woman” in American Identity and the Transatlantic Irish Nationalist Movement, 1912-1925, by Catherine M. Burns towards the requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy (History), University of Wisconsin, Madison, 2011. p. 180.

[28] “American-Irish Women Picket John Bull’s ‘American Citadel’ “, Irish News and Chicago Citizen, April 9, 1920. Digital copy obtained April 23, 2019, from Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library microfilm collection. Cited in Note 32, p. 284, of “True Women, Trade Unionists, and the Lessons of Tammany Hall: Ethnic Identity, Social Reform, and the Political Culture of Irish Women in America, 1880–1923,” by Tara Monica McCarthy toward requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy, Department of History, Arts & Sciences, University of Rochester, NY, 2005.

[29] Burns, “American Women”, p. 184.

[30] “Building the Commonwealth,” Freeman, May 26, 1920, 252–254; and “The Countesses’ Constituency”, Ibid., Sept. 1, 1920, 588–9.

[31] Patrick McCartan, With de Valera in America, (New York, Brentano, 1932), p. 177. McCartan names the Chicago Daily News as among anti-Irish “journals that Britishers edit,” along with the New York Times, Providence Journal, and Christian Science Monitor, p. 121.

[32] Russell, Ireland?, 13. She does not name the “fellow journalist.”

[33] The (Brooklyn, N.Y.) Tablet, Aug. 28, 1920, p. 5; The Nation, March 23, 1921, p. 441

[34] “The Trouble with Ireland,” New York Tribune, Sept. 12, 1920.

[35] “What’s the matter with Ireland?” Catholic World, December 1920, p. 396.

[36] “The American Commission on Conditions in Ireland, Interim Report“, 1921, pgs. 1–2.

[37] Evidence on Conditions in Ireland, p. 427.

[38] Ibid., p. 432.

[39] Ibid., p. 436.

[40] Ibid, 462.

[41] Ibid, 461.

[42] Washington, D.C., Bureau, News Dispatches, Dec. 1-16, 1920, pages 863 & 864, MS Washington D.C. Bureau at the Library of Congress: Washington, D.C. Bureau Records, 1915 – 1930 70; 2. Manuscript Division, Library of Congress. Associated Press Collections.

[43] “America and Ireland,” Evening Herald (Dublin), Dec. 30, 1920.

[44] Ruth Russell’s Chicago Public Schools (CPS) employment record, and 1932 Calumet High School Yearbook, Chicago, Ill. U.S. Yearbooks Name Index, 1890–1979 via MyHeritage.com.

[45] Ruth Russell, Lake Front (Thomas S. Rockwell: Chicago, 1931), pgs. 173, 182.

[46] “Chicago’s First One Hundred Years”, Hyde Park Herald, Sept. 18, 1931.

[47] Passport and ship passenger records for Ruth and Cecilia Russell, their identities confirmed by birth date and shared Chicago address. 1923 itinerary shows “British Isles and France.” 1939 trip shows return from Cobh, Ireland. Ellis Island and Other New York Passenger Lists, 1820–1957, MyHeritage.com.

[48] State of Illinois Medical Certificate of Death, Nov. 29, 1963, Cook County (IL) Clerk’s Office, Bureau of Vital Records, Genealogy Records Division. Chicago Daily News, Nov. 30, 1963; Chicago Tribune, Nov. 30, 1963; and Northwest Arkansas Times, Dec. 2, 1963.