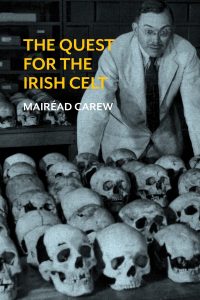

Book Review: The Quest for the Irish Celt: The Harvard Archaeological Mission to Ireland, 1932–1936

By Mairead Carew

By Mairead Carew

Published by: Irish Academic Press, 2018.

Reviewer:Timothy Ellis

Every now and then, it does historians good to take a step back and ask an important question: “How does our own time influence our writing of history?”

Mairead Carew’s Quest for the Irish Celt is a lively meditation on this question. As she reminds the reader frequently, archaeology in the Irish Free State was, very much, a product of its own time. In the 1930s, a team of anthropologists and archaeologists from Harvard University visited Ireland to study its people; past and present.

In the 1930s a team of archeologists from Harvard University attempted to discover the origins of the Celts in Ireland.

The ‘Harvard Irish study’ incorporated archaeology, physical anthropology and social anthropology. The social anthropological investigations of this expedition, conducted by Conrad Arensberg and Solon Kimball, which examined rural life in County Clare, is well known. Arensberg and Kimball painted a picture of a conservative society, marked by gerontocracy, emigration and sharply defined gender roles.

For many, Arensberg’s and Kimball’s observations epitomise the conservative insularity of the Irish Free State.

Historians and the general public have long regarded the Free State as a conservative, rural backwater to Europe, which had forgotten the revolution that had created it, and thus remained isolated from the radical influence of the Interwar period.

However, Carew argues that, in fact, in Irish archaeology and anthropology in this period, intellectual influences from Germany and the United States were very strong. Whilst the social anthropology strand of the Harvard Expedition is well known, its archaeological excavations and investigations into the physical anthropology of the Irish people has not attracted as much attention. Yet both these strands were immensely significant, not least because both were influenced by contemporary thought on racial ‘science’ and eugenics.

The Harvard Expedition

The Harvard expedition was managed by Earnest Hooton, who had contributed much to these pseudoscientific fields. Similarly, the Director of the National Museum of Ireland, who advised the expedition, Adolf Mahr, was the Leader of the Nazi party in Ireland. Carew highlights the ways in which multiple factors; political, economic, cultural and social, influenced the Harvard team’s research in Ireland, and illuminates multiple intellectual connections between Ireland, Europe and the United States in this period.

Chapter 1 explores how popular understandings of archaeology informed Irish political ideologies and vice-versa. As Carew argues, ‘Monuments and artefacts applied a sense of concreteness, permanence and longevity to the abstract concept of nation.’ Douglas Hyde, the apostle of ‘Irish Ireland’ himself, argued that ‘our antiquities can best throw light upon the pre-Romanised inhabitants of half Europe.’

Nonetheless, as Tom Nairn argues, nationalism is Janus-faced: it looks both forward and back. Carew notes that the ‘scientific’ authority of anthropology and archaeology was deemed appropriate to serve a distinctly modern state, which was looking to define itself in relation to a community of European nations.

The Irish state itself gave support to Irish archaeology through the 1930 National Monuments Act and commissioned a Swede, Nils Lithberg, to write a report on the purpose of the National Museum. One of his recommendations was that, collections should be “firmly based on Ireland’s native culture.”

Archaeologists would also prioritise and emphasise the importance of objects from the Early Christian period, so as to underline the state’s Catholic credentials. Both the democratic and nationalist inclinations of the Irish state and de Valera’s government, in particular, fed into the Lithberg report, and he recommended that the Museum’s collections should ‘embrace all classes’.

The second chapter hones in further on the institutional aspects of Irish archaeology during the Harvard Mission, and explores the process by which the Harvard Mission chose Ireland as a research site. Whereas previously, archaeology had been practised by amateur ‘dilletante’ Anglo-Irish antiquarians, by the 1930s, archaeology was becoming increasingly professionalised. The state looked for expertise from Europe, thus undermining the long-held authority of Anglo-Irish ‘experts.’

A German, and a member of the Nazi party, Adolf Mahr was appointed as Director of the National Museum in 1934, something which the Ulster archaeologist, Estyn Evans regarded as illustrating “the hatred of all things British prevailing in Éire in the years following partition.” As Carew argues, Mahr’s own eugenic beliefs were not dissimilar to those of members of the Harvard team.

The quest for the Celts

The third chapter explores the main research question for the Harvard team: establishing when then Celts first came to Ireland. Mapping out the racial origins of the Irish people naturally appealed to Irish Americans, some of whom funded the Harvard Mission.

At a time when non-European migration into the United States was heavily restricted, the Irish diaspora were keen to emphasise their credentials as white Europeans. Research on the “Celtic” origins of the Irish people was thus helpful in this respect. Earnest Hooton had a strong interest in anthropometry: the physical measurement of facial/bodily characteristics in order to classify racial origins.

At a time when non-European migration into the United States was heavily restricted, the Irish diaspora were keen to emphasise their credentials as white Europeans.

Racial classifications made through anthropometry were used to justify American immigration laws, and it was believed that undesirable behaviours such as criminality, laziness and drunkenness could be ascertained through physical attributes.

As Carew notes, ‘Simian-type stereotyping of the Irish Celt, with negroid features, had been popular in American and British newspapers published in the nineteenth century.’ However ‘scientific results obtained by the Harvard academics rivalled those imaginative and discriminatory depictions,’ and thus painted a picture of the Irish people as being far more akin to white Northern Europeans, with Scandinavian features.

Archaeological excavations also pointed towards particular racial origins. A particular area of interest for the archaeological strand of the Harvard Mission was the excavation of Crannógs (lake dwellings). Three crannógs were excavated in Counties Meath, Westmeath and Offaly.

We see in Chapter 4 how crannógs were chosen as sites for excavation for ideological, as well as scholarly, reasons. Crannógs were lake islands which offered their inhabitants defence and protection against invaders, and as Carew notes, their perceived importance reflected ‘a Darwinian view that cultural change and adaptation to the environment is essential to survival.’

Although the Harvard team were keen to paint a picture of racial purity amongst the ancient Irish, they had to be careful not to over-emphasise cultural continuity. As Carew argues, ‘a lack of cultural change could… suggest a lack of progress and in-adaptability to a changing environment.’ Indeed ‘the “more Irish than the Irish themselves” motif in Irish history accommodates the idea of invasion with that of cultural continuity.’

A story of both invaders and natives adapting to changed circumstances thus maintains a degree of cultural continuity, but also emphasises adaptability and the ability to survive. Within the excavations themselves, the archaeologists were keen to highlight objects which suggested the presence of invaders, particularly those who were ‘racially superior’, i.e. Northern Europeans. At the Crannóg at Ballinderry, for instance, a Viking gaming board was a ‘star find.’

Chapter 5 follows on by exploring the excavations at the Lagore crannóg, and here, Carew examines the ways in which the excavations at this particular site were interpreted to suit certain narratives and ideologies. Hugh O’Neill Hencken, Director of the Archaeological Strand of the Harvard Mission, for instance, argued the inhabitants of the Lagore Crannóg were undoubtedly Christian.

Nonetheless, at this site, the team did not recover any ecclesiastical objects, and there was no evidence of Christian burial practices. Moreover, whilst at Ballinderry, the excavators were happy to highlight ‘Norse’ artefacts, at Lagore, items which were of ‘Roman’ provenance were readily explained away, lest it threaten a nationalist narrative of Ireland’s stance as a small, independent against the Roman Empire.

The archaeologists were not keen to offer evidence which contradicted pre-existing documents and texts. Since the crannóg came from a period which had long been dubbed ‘early Christian,’ Carew argues that the Harvard archaeologists could ‘not penetrate the thickness of the walls of a well-established Irish antiquarian tradition.’

Chapter 6 examines the Harvard mission’s work in Northern Ireland and how this also fed into Irish nationalist ideology. Adolf Mahr, of Sudeten German origin, naturally saw strong parallels between his homeland and Ulster. Mahr believed that prehistoric, ancient boundaries were more authentic than ‘modern’ ones (i.e. those boundaries drawn after the First World War).

Whilst the Harvard team were keen to highlight objects which suggested the existence of ‘Irish culture’ in Ulster, they were afraid of finding particularly old skeletons in the province, lest it suggest that the ‘first Irishmen’ had settled in Ulster, and had thus most likely come over from Great Britain.

Conversely, the Ulster archaeologist, Emyr Estyn Evans wrote of ‘saints and sinners alike moving to and from across the turbulent seas between western Scotland and the north of Ireland,’ so as to promote a British Unionist ideology.

Archeology and the de Valera’s Ireland

The following chapter highlights another area where political ideologies influenced academic questions: that of economic policy. During the 1930s, as a result of the Great Depression, governments across the world experimented with economic interventionism, in particular the sponsorship of public works schemes. This was true of both Franklin D. Roosevelt’s ‘New Deal’, in the US, and Éamon de Valera’s Fianna Fáil government in Ireland.

The Harvard expeditions in Ireland used unemployed labour to assist with digging and excavations, and the 1930s thus marked ‘the first time that archaeological excavations were not just carried out for cultural reasons, but were used by the government in a broader social and economic context.’ Public work schemes at these archaeological digs were ‘important community initiatives in archaeology which provided work for the local people and gave them a sense of ownership and pride in monuments in their locality.’

This chapter, in highlighting, more pragmatic socio-economic factors, as well as nationalist ideology, in influencing the excavations is particularly interesting. It would have perhaps been good to have perhaps a little more detail here on the ways in which de Valera’s economic policies influenced the archaeological practices of the Harvard Mission.

As previously mentioned, nationalism looks both forward to the future, and back to the past. In the Irish Free State, politicians were keen to construct Ireland as a ‘modern’ state as well as arguing for the sanctity of the Irish past. In the same way, the Harvard Mission injected ‘modern science’ as well as a restoration of past glories into the Irish cultural landscape.

Irish politicians were keen to construct Ireland as a ‘modern’ state as well as arguing for the sanctity of the Irish past and the Harvard Mission injected ‘modern science’ as well as a restoration of past glories into the Irish cultural landscape.

Chapter eight examines the ways in which the Harvard team utilised scientific approaches, which marked a departure from older, more ‘antiquarian’ methodologies that had previously been used in Irish archaeology. There was a shift away from collecting exotic artefacts for their own sake, to thorough, careful excavation, which preserved as much of the archaeological record as was practicable. As one of the archaeologist noted, workers on the sites had to learn ‘that they are not digging for buried treasure and that a post-hole is as important as a portable find and that they must exercise care at every stage.’

The Harvard mission employed new techniques involving theodolites, quadrants and photography, as well as pollen and charcoal analysis, for the first time in Ireland. Nonetheless, as we have already seen, older, more established intellectual frameworks did endure, and Carew argues that ‘embedded notions about Celtic or Christian identity… [remained] neither explored nor challenged.’

The final chapter explores the project’s engagement with Irish audiences on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean. Carew argues that the Harvard Mission was part of a wider sea-change in Irish-American’s self-image. Whereas ‘the term “Celtic… was a term of racist abuse for the Irish in the English and American media in the nineteenth and early twentieth century’ it became increasingly associated with Irish and diaspora nationalism.

The findings of the project were widely disseminated to a wide audience, using the resources of both the modern media and nation-state. Radio programmes on both sides of the Irish border discussed the Harvard Mission, and the Irish government published a booklet National Monuments of the Irish Free State, which incorporated the project’s finds.

Interestingly, it did not cover any archaeological finds in Northern Ireland. Hugh O’Neill Hencken’s article ‘Harvard and Irish archaeology’ featured in the catalogue of the The Pageant of the Celt, a re-enactment of episodes in Irish history at the Chicago World Fair in 1934.

This ‘pageant’ was pitched at Irish Americans, and sought to ‘awaken in them a just pride of race and a faith in racial destiny.’ As Carew reminds us ‘the discourse on the Celts was primarily around the issue of race, which was the prominent ideology of the times.’ Although the Harvard project concerned itself with the internal question, equally, as Carew concludes, it was also eminently ‘modern’ and sought to define Ireland’s place in the modern world.

A valuable contribution

The Quest for the Irish Celt takes an under-explored subject and offers an accessible, inter-disciplinary analysis. Mairead Carew comes from an archaeology background, yet succeeds in writing a book which professional archaeologists, experienced historians of Ireland and general readers, alike, will find both fascinating and informative. One does not need much expertise in archaeology to appreciate and understand this book’s arguments.

Carew simultaneously writes about abstract theory and concrete examples lucidly. There is an effective balance between detailed discussion of the archaeological excavations and analysis of a wider socio-economic, cultural and political context.

The research behind this book is also of a high quality. Carew has consulted the archives of the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology at Harvard and the National Museum of Ireland to offer considerable detail on the archaeological digs.

She has also clearly done large volumes of research in the Archives of University College, Dublin and the National Archives of Ireland, which has aided her research into the Harvard Mission’s political, social, economic and cultural context. As mentioned previously, the latter body of sources might have been used a little more extensively in Chapter 7 to draw out connections between the Harvard Mission and dominant economic ideologies in the 1930s.

Mairead Carew tackles these topics courageously, and make good stimulating food for thought in the present day, as the issues and problems of nationalism figure heavily in the political landscape.

The monograph is well laid-out and presented, and is handsomely illustrated with well-chosen images. Some minor tweaks to the structure might have improved the ‘flow’ from chapter to chapter. For instance, Chapter 7 (which explores links between the Harvard mission and de Valera’s economic policies) might have complemented some of the points made in the first and second chapters (which discuss the broader role of the Irish state in Irish archaeology).

That said, this book makes several important contributions to Irish historiography. One of these contributions is obvious, though by no means insignificant: Carew offers us a history of Irish archaeology in a transformative period. Whilst cultural historians in Ireland have written extensively on education, language, literature and theatre, there has hitherto been little work which places Irish archaeology in a historical context.

Whilst the influence of the politics of Irish nationalism on Irish historiography has been extensively documented and debated, Carew sheds considerable light on its influence on Irish archaeology, and in turn the writing of early Irish history. Carew also considers another difficult topic: that of race. Surprisingly little has been written on the place of race and ethnicity in Irish nationalism.

As Carew suggests however, in the early twentieth century, constructions of Irish nationhood and nationalism were heavily predicated upon notions of European heritage and culture, and above all, whiteness. Some of the passages on Adolf Mahr, and on the eugenic beliefs of the Harvard Mission make for quite uncomfortable reading, especially when we consider the broader international context to Ireland in the 1930s.

Nonetheless, Carew tackles these topics courageously, and make good stimulating food for thought in the present day, as the issues and problems of nationalism figure heavily in the political landscape.