Book Review: Into Action, 1960-2014 Irish Peacekeepers Under Fire

By Dan Harvey

By Dan Harvey

Published by Merrion Press,

Newbridge, 2017

ISBN: 9781785371110

Reviewer: Gordon O’Sullivan

“The Irish Defence Forces’ involvement in overseas peacekeeping service was to prove the single biggest development in their history”.

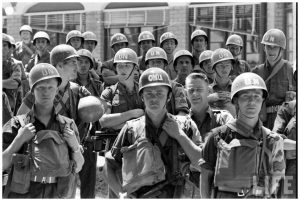

When Ireland sent troops to the Congo in 1960 to take part in its first armed United Nations peacekeeping mission, ONUC (the Operation des Nations Unies au Congo), it could never have been envisaged that nearly sixty years later its Defence Forces would have served some 85,000 individual tours of duty on 70 UN missions across almost every continent.

Irish soldiers have served 85,000 individual tours of duty on 70 UN missions across almost every continent since 1960.

While the Irish public now fully accepts and respects the Irish Army’s UN overseas service, it was in 1960 “an entirely ‘New Departure’”. Indeed, as Dan Harvey points out in his book Into Action, 1960-2014 Irish Peacekeepers Under Fire, participation in its first UN action was fully transformative for the Irish Defence Forces, “the single biggest development in their history”.

UN service has become in fact the only combat opportunity for the men and women serving in the Defence Forces and has proved a vital operational outlet for Irish soldiers, helping to create a modernised army able to deliver on its military mandates in the most demanding of circumstances.

Unfortunately, this service has not been without a significant human cost. With all the positives of UN military service have come the negatives of the deaths of eighty-six members of the Irish Defence Forces.

Eighty six members of the Irish Defence Forces have died on UN service.

It is with those engagements that took the lives of Irish servicemen that Dan Harvey, a veteran of UN peacekeeping missions, concerns himself in Into Action. He has selected the major firefights in which Irish troops were involved on UN service and explores in detail Irish soldiers battling Baluba tribesmen, Belgian mercenaries, Israeli-backed militias, rioting Kosovar Albanians, Chadian rebels, and Islamic militants in diverse locations ranging from the Congo to the Lebanon.

As the first armed UN mission undertaken by Irish soldiers and the overseas operation with the most sustained fighting overall, the Congo takes up a large portion of Into Action. Harvey, a former Lieutenant Colonel in the Defence Forces, describes the initial teething problems for what was a completely new experience for the Irish Army. While the Defence Forces had made its first contribution (50 unarmed officers) to peacekeeping in 1958 with UNOGIL in Lebanon, Irish soldiers were completely under-prepared, inexperienced and under-trained for what would be a baptism of fire in Africa.

Irish troops in the Congo were badly prepared for a peace-enforcing mission

After all, as Harvey astutely points out, “it was fifteen years since the ‘Emergency’ ended in 1946” and there had been no large-scale deployment of Irish troops in the ensuing period.

Certainly, the Irish public was not prepared for the worst possible beginning to Ireland’s peacekeeping adventures when “only three months after the first Irish contingent…were deployed amid a mood of national exhilaration”, nine soldiers of the 33rd Irish Battalion were killed in an ambush by Baluba warriors, the biggest loss of life the Irish Army has ever had in one action.

This ambush, near Niemba, “was a stark reality check and loss of innocence for Ireland” with over 500,000 people lining the streets of Dublin for their funerals.

Niemba was only the first of the fights that the Irish became embroiled in during their Congo mission. Harvey describes the now celebrated Siege of Jadotville in September 1961 in great detail. In his account of how 156 lightly armed Irish soldiers fought off 4,000 heavily armed Katangan Gendarmerie and mercenaries for six days until their eventual surrender, the author has little new to add to the excellent books on Jadotville by both Rose Doyle and Declan Power.

However, in what is one of the longest sequences in the book, Harvey skilfully marshals first-hand accounts to describe the final large scale Irish engagement in Congo at the Battle of the Tunnel in Elizabethville. He underlines the testing conditions the raw Irish soldiers experienced during their tour of duty, “shot at on touchdown, subjected to several attacks since and under constant mortar and sniper fire, the Irish had been heavily pounded for the last four days.”

Harvey served in the Lebanon and the chapter on the Irish experience there is the strongest section of the book.

The account of Irish involvement in Lebanon is the strongest section of Into Action and here Harvey deploys his own personal experience to best effect. Using evocative photos and pertinent chunks of first person accounts, Harvey attacks his account of the Irish Middle East missions with gusto, confidently asserting that “in terms of longevity and commitment, UNIFIL is by far the most important overseas mission ever undertaken by the Irish Defence Forces”.

The focus of the ‘Leb’ section is the village of At-Tiri in April 1980, where the DFF (De Facto Forces, an Israeli-backed Christian militia) attacked Irish troops reinforced by Dutch and Fijian peacekeepers. Over the next seven days, the peacekeepers were intent on not escalating the confrontation further while at the same time not backing down in the face of the DFF aggression.

Harvey considers that on this high wire act the “credibility of the UNIFIL mission…the will of the UN” depended. However, as the author describes it, the Christian militia had picked the wrong soldiers to try and provoke, “the discipline of no-escalation, despite provocation, is the hallmark of peacekeeping and the Irish were among the best.”

Dan Harvey has produced a very useful guide to the main engagements that the Irish Defence Forces have fought on UN service.

Amid all the flying shrapnel Harvey picks out some wonderful light moments, particularly the Irish piper playing ‘Wuthering Heights’ at dawn on a village rooftop, “a rendition loudly applauded by the other Fijian and Dutch UNIFIL reinforcements.” After seven days of standoff the Irish and UN troops finally prevailed and the DFF pulled out. One Irish soldier died in the fighting and two more were subsequently kidnapped and murdered by the DFF in retaliation for this battle at At-Tiri.

More recent UN engagements are given less space with shorter sections on deployments to Kosovo, Chad, and Syria. An account of how the Defence Forces helped defuse Kosovo’s ‘Mid-March Riots’ in 2004 is brief. Irish participation in the EU’s military mission, EUFOR, intervening in the civil war in Chad to protect refugee camps, is succinctly detailed with an interesting contribution from its former commander, Lieutenant General Pat Nash.

The section on Chad emphasises the positive effects of UN peacekeeping missions on the Irish army and shows how their military skills had been sharply honed over the decades of overseas service, “the Defence Forces were leaner, better equipped, prepared and more professional than ever before and it was all manifesting itself in Chad.” Conversely the army’s recent deployment to the Golan Heights during the height of instability in that region is given relatively short shrift despite a dramatic gun battle with Islamic militants.

While one could perhaps wish for a more in-depth teasing out of the arguments for and against Irish participation in military operations overseas, Dan Harvey has produced a very useful guide to the main engagements that the Irish Defence Forces have fought on UN service. In the process, he helps underscores why Irish people should be proud of both past and continuing Irish military contributions to United Nations peacekeeping efforts.