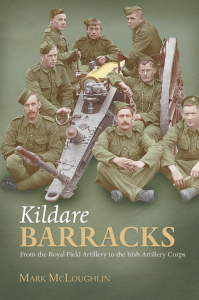

Book review: Kildare Barracks

Kildare Barracks: From the Royal Field Artillery to the Irish Artillery Corps

Kildare Barracks: From the Royal Field Artillery to the Irish Artillery Corps

By Mark McLoughlin

Published by Merrion, Sallins, 2014

ISBN: 9781908928474

Reviewer: Gordon O’Sullivan

“Amongst all the arts that adorne the life of man on earth…Yet none comparable to the art and practice of artillery, ‘The Arte of Shooting Great Ordnance’, London, 1587.

Kildare Barracks was integral to Kildare town for almost a century with the British Army arriving in 1902 and the Irish Army leaving in 1998. Two world wars, the Irish War of Independence and Civil War, the modernization of the army in the 1940s and 1950s and the transition to peacekeeping roles with the United Nations all occurred during that span of time. Mark McLoughlin, an experienced local history writer, positions Kildare Barracks: From the Royal Field Artillery to the Irish Artillery Corps not as a definitive history of the barracks but rather “a glimpse into the units and men” that served in Kildare barracks and a record of the lasting impression they left on their surroundings.

McLoughlin divides his book into two parts, the first chronicling the British garrison from 1902-1922 and the second covering the Irish barracks from 1922-1998. Through both a mixture of personal histories of the gunners stationed in Kildare Barracks and voluminous official records of their units, the author fully explores their military lives and experiences.

British Barracks 1900-1922

The construction of the barracks in 1900 had a huge impact on the town of Kildare and provided a period of considerable prosperity for its inhabitants. When the first units of the Royal Field Artillery, many of whom were veterans of the Boer War, arrived two years later to the modest wooden huts of the camp, they almost doubled the population of the town and substantially changed the religious composition of the townspeople. The barracks also had a physical impact on Kildare with drastic improvements in town water and sanitation services.

Their arrival also brought electric lighting in both the town and barracks which the town leaders were delighted about; allaying in part their concern that darkness would allow immoral behaviour with such a large military population nearby. Many of the gunners in their turn were shocked at the size and rural nature of their new station. McLoughlin is particularly effective here and creates a vivid sense of the changes wrought by the new camp. Some wonderful photos, both from the author’s own collection as well as archive sources, also complement this section of the book.

The British Royal Artillery garrison were generally popular locally due to the major economic boost they gave to Kildare town in their 20 years garrison there.

Most of these men went on to serve in the First World War as soon as it broke out in 1914 and the onset of hostilities caused great upheaval in both the barracks and the town. All leave was cancelled and the local railway station was taken over by military intelligence. Kildare Barracks was practically cleared as the gunners of the 15th Brigade Royal Field Artillery (RFA) were despatched for France in August as part of the British 5th Division.

Despite the unsettled political atmosphere in Ireland at the time, the town did support the gunners on their departure with the Kildare Observer reporting that “though it was 2 o’clock on Sunday morning, never the less a large crowd of Kildare Townspeople assembled to cheer them off and this was repeated on Monday morning at 7 o’clock.” Despite this show of support, the local Irish Volunteers still had to publicly defend the use of their band at the send-off. McLoughlin points out that the primary concern for the townspeople was not however the fate of the soldiers but the loss of business when the RFA left Kildare. It was a major economic blow for the town.

Troubled times

The murder of Lieutenant John Wogan-Browne and its potential destabilising effect on Anglo-Irish relations in 1922 gets its own chapter, perhaps not surprising when the author had previously won a prize for his writing on the subject. However McLoughlin’s concentration on Wogan-Browne is merited as this is perhaps the strongest chapter of the book, providing a fascinating insight into the tensions it caused during this period of transition to the new Irish Free State. The facts of the case are simply put.

During the period of the truce in early 1922, a British officer was shot dead near the barracks, causing Michael Collins to assure Winston Churchill he would find the killers.

On the 10th February 1922, Wogan-Browne, a serving British officer stationed at Kildare Barracks and member of a well-to-do Naas family, had collected the regimental pay of £135 from the Hibernian Bank in Kildare when he was held up by three men. In the ensuing tussle, Wogan-Browne was shot in the head and the robbers fled. This was an incident that shocked local opinion, the Kildare Observer commenting that “no incident that has occurred in County Kildare within living memory has occasioned more widespread horror and condemnation.”

McLoughlin chronicles the aftermath meticulously. All passes for traders to the barracks were cancelled and on the night of the funeral, British soldiers caused considerable trouble in the town. The murder also caused political problems forcing Michael Collins to send a telegram to Winston Churchill assuring him that “everyone, civilian and soldier has co-operated in tracking those responsible for abominable action.

You may rely on it that those whom we can prove guilty will be suitably dealt with.” Three local men were arrested for the murder but later released. This event heightened British fears of being attacked during this transition; they were particularly concerned about getting their families safely out of Ireland. Eventually, the barracks was handed over to the Provisional Government on Saturday 15 April 1922 and the short British stay in Kildare Barracks was over.

The barracks now became the headquarters and training camp for the new Civic Guard police but the febrile political atmosphere would not allow a calm beginning to Irish ownership. There was almost immediate dissension in the ranks of the new police recruits when they realised that some of their instructors were former RIC men.

In May 1922, new Civic Gaurd police units stationed at the barracks mutinied.

Tensions continued to rise until finally, on 15 May 1922, a mutiny ensued with the ringleaders demanding the expulsion of five of these former RIC men from the force. The following day, the mutineers went further and raided the armoury and barricaded themselves in. Soldiers from the Curragh and in the ensuing stand-off they threatened to storm the gates of the barracks.

Michael Collins had to step in and came down to Kildare to meet the mutineers, eventually agreeing to set up an enquiry into their demands. McLoughlin argues convincingly that this mutiny had a large impact on the civic guard’s eventual transformation into an unarmed force with strong links to the community.

Irish artillery barracks 1925-1998

It wasn’t until February 1925 that the barracks once more housed an artillery unit with the arrival of the new Artillery Crops of the Irish army. They came from the train station, according to one witness, “at full tilt with outriders on the lead horses urging them on, drivers shouting, whips cracking, horses galloping and gun and limber wheels crashing on metalled road.”

The Artillery corps was still of course dependent on horses, perhaps appropriately for a corps based in Kildare horse country, and gunners still had to wear spurs on duty throughout the 1920s and 1930s. McLoughlin contends that the Artillery was always the most prestigious element of the army with only the brightest and best men, a claim which should provoke some challenges from readers who have served in other sections of the Irish army.

The Irish Army artillery corps occupied Kildare barracks from 1925 until 1998.

Only when the Second World War was underway were the gunners finally allowed to remove their spurs as the horses finally departed during the Irish Army’s much needed modernization. This also meant a new building for Kildare Barracks in 1939, the first barracks to be purpose-built by an Irish government. This new barracks was renamed Magee Barracks in 1952, after gunner James Magee from the battle of Ballinamuck in September 1798.

Modernization of the guns themselves was also undertaken with the introduction of the 25-pounder field gun in 1949, a gun which had served the British well during the Second World War. Forty-eight guns were purchased and served the corps for sixty years. In 1980, most of the 25 pounders were replaced by the British 105mm light gun; it was mobile and could be carried by helicopter. This decision was taken by an army board after they had discarded the Russian 122mm on the grounds that “this is Catholic Ireland, we can’t be using communist guns!”

The end for the barracks was sudden. On 16 July 1998 the then Minister for Defence, Michael Smith, arrived on short notice and told the assembled men that the barracks was to close as soon as possible. On 24 September 1998 the tricolour was lowered and the gunners left Magee Barracks for the last time.

This book will be of interest to anyone with an interest in Kildare local history, the Irish army or the British army in the early 20th century

This book will be of interest to anyone with an interest in Kildare local history, the Irish army or the British army in the early 20th century and has laid firm foundations for further study in these areas. Mark McLoughlin has told the story of a national military institution and the personnel who passed through it with a commanding level of detail. While, particularly in the second part of Kildare Barracks, the narrative is sometimes overwhelmed by the number of lists and records provided, McLoughlin’s mining of local and national archives has provided some fresh insights on major events in Irish modern history.