Today in Irish History – August 31, 1913 – Labour’s Bloody Sunday

The first ‘Bloody Sunday’ in twentieth century Ireland, during the Lockout of 1913. By John Dorney See also Remembering the Lockout.

It was around half-past one on O’Connell Street, the wide boulevard right in the heart of Dublin city. The street was crowded, as usual on a Sunday, with strollers. The city was tense, as since that Tuesday the Irish Transport and General Workers’ Union had called a strike on the Dublin United Tramway Company, owned by William Martin Murphy.

There had already been fierce rioting between the strikers and the police. However the scene on O’Connell Street was peaceful. A planned meeting by James Larkin and the Transport Union on O’Connell Street had been banned by Dublin Castle the workers were holding a rally in Croyden Park Fairview, north of the city. Larkin himself was evading arrest, he had been charged with incitement to breach the peace.

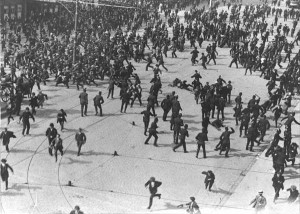

Police baton charged a crowd on Dublin’s O’Connell Street after arresting union leader James Larkin

Passersby noticed some commotion at one of the windows of the Imperial Hotel (itself part of Murphy’s business empire). It was Larkin, keeping a promise to his supporters to speak that day on Dublin’s main thoroughfare, in spite of the authorities’ directives.

Scarcely had Larkin begun to speak when he was arrested and all hell broke loose on the street below him. The police on O’Connell Street, roughly 300 strong, both the Dublin Metropolitan Police and detachments of the Royal Irish Constabulary, drafted into the city for the strike, had been nervously awaiting an outbreak of disorder. One sergeant mistook a surge in the crowd for an attack on the police.

Now they charged the crowd, mostly of curious onlookers. A watching MP Handel Booth said that the police, ‘behaved like men possessed. They drove the crowd into the side streets to meet other batches of the government’s minions, wildly striking with their truncheons at everyone within reach…The few roughs got away first, most respectable people left their hats and crawled away with bleeding heads. Kicking victims when prostrate was a settled part of police programme’.[1]

The Red Hand

The previous Tuesday, August 26, shortly after 9 am, Transport Union members in the Dublin United Tramway Company had pinned on their ‘red hand’ union badges and walked off the trams, telling passengers, many of them well-heeled Dubliners heading for the annual Horse Show, to get off and walk.

On June 26, Transport Union members in the Dublin United Tramway Company pinned on their ‘red hand’ union badges and walked off the trams, telling passengers, many of them well-heeled Dubliners heading the annual Horse Show, to get off and walk

It was the culmination of a bitter dispute over union recognition. William Martin Murphy had formed a Dublin Employers’ Federation with the aim of halting the growth of Larkin’s militant union, the ITGWU. He and his allies issued a pledge to workers to resign from the ITGWU and not associate with any member of it or be dismissed. Already by this date a significant number, 200, had lost their jobs. Larkin called the strike, at the request of his sacked members, seeking their re-instatment.

However, things did not go their way. Only around 200 out of 650 tramway workers had left their jobs. By the evening of August 26, the trams were already back in action. Murphy had a supply of strike-breakers on hand and the trams were guarded by large contingents of the Dublin Metropolitan Police.

Over the next four days, there was serious violence between them and the strikers as the workers tried to halt the running of the trams.

The dispute moreover was already escalating. Murphy’s Federation of Employers was issuing more widely the pledge to workers not to associate with the ITGWU and sacking those who would not take it. At the same time, Larkin pressured other unions not to handle the goods of companies who had locked out their workers, spreading the dispute still further.

Many other trade unionists were annoyed by Larkin’s handling of the affair, putting them in a position where they had to choose between their jobs and solidarity with fellow workers. Gary Holohan, for instance, who worked at Ringsend Power Plant thought:

This strike started with the building trades and spread from one trade to another. We escaped for a good while. Then the coal merchants became affected. At that time we were receiving our coal from Nicholls. The Chief Engineer offered to get a cargo of coal straight from England, and as the sailors were members of a Trades Union it appeared to be quite a reasonable arrangement, but the union was not satisfied.

When Nicholls sent the first motor lorryload of coal, the trimmer refused to take it in and he was dismissed. The other men were asked in turn and they all refused and were dismissed. Then the crane drivers and the engine drivers were called out in sympathy. Some went out and others stayed in. For the first couple of days there was no one but the two foremen to keep the power-station working, and they had to fire the boilers.

The engineers and fitters did not go on strike so I was not affected because at that time I was an apprentice member of the Amalgamated Society of Engineers. While I was in full sympathy with the men who were on strike, we thought it was ridiculous of Larkin to take them out instead of making the other arrangement.[2]

The dispute quickly escalated, so did the violence

Violence also escalated in the following days. At Ringsend bridge, fighting broke out between police and picketers trying to halt trams bringing some 6,000 spectators to a football match at Shelbourne Park between Shelbourne and Bohemians (the latter of whom, Larkin alleged, had a number of ‘scabs’ playing for them). By the day’s end sixteen men had been arrested and over 50 put in hospital, including two policemen.[3]

Along Brunswick Street (now Pearse Street) more rioting took place as strikers attempted to halt the trams going to and from the city centre. More rioting took place in and around the Customs House and union headquarters at Liberty Hall. A ‘mob’ of 4-500 people at Corporation Buildings in the north inner city repulsed a police charge, chanting, ‘down with the bloody police’ and (especially, apparently, the women), pelting them with stones from the upper floors of the building.[4]

Gary Holohan remembered that when a strike breaker arrived at the Ringsend Power Station, one striker, ‘followed him home with another fellow and I heard that they hit him on the head with a pot, with the result that he never returned to the power-station’. He himself also participated in rioting, ‘James Connolly sent down a supply of slings that were made in Belfast, and I remember having a crack at tram windows in Harcourt Street and making a run from police through one of the side streets until I reached the Fianna Hall in Camden Street’.[5]

James Larkin went into hiding, charged with incitement to breach the peace. His lieutenant, James Connolly was also arrested and told the authorities, ‘I do not recognise the English government in Ireland at all. I do not even recognise the King except when I am compelled to do so’[6]. A rally of the workers on O’Connell Street was proscribed by the British authorities, based in Dublin Castle.

By Sunday, some of the cooler heads in the ITGWU such as William O’Brien and PT Daly, anxious to avoid more violence, called off the rally and instead called for a march to Croyden Park and a rally there, where it was less likely they would have to confront the police.

Larkin, however was never a man to back down from a fight, or to heed cool heads. Wearing a beard as a disguise, he was smuggled into O’Connell Street and appeared at the balcony of the Imperial Hotel, provoking his own arrest, the police baton charge and mayhem in the street below.

Labour’s Bloody Sunday

According to Ernie O’Malley, who was merely passing by that day when the police charged; ‘Police swept down from many quarters, hemmed in the crowd and used their heavy batons on anyone who came in their way. I saw women knocked down and kicked. I scurried up a side street; at the other end, the police struck people as they lay injured on the ground, struck them again and again. I could hear the crunch as heavy sticks struck unprotected skulls.’[7]

At least two people were fatally injured in the first weekend of the strike and as many as 600 injured

Stephen Prendergast, a member of the nationalist youth organisation the Fianna, whose leadership supported the strikers, was in Croyden Park that day, but his account of another riot on O’Connell Street shortly afterwards gives us an idea of what it must have been like to be on the receiving end of the police batons that day;

Suddenly the cry was heard, “a baton charge”, and immediately there was utter confusion. The whole Street, or the people who were, unfortunately, traversing it, was set in motion. People ran hither and thither, the police on their heels chasing them. No time to ask questions, how or why this happened? I found myself, like other folk, running away from a group of policemen who were behind us wielding their batons.

I made to get into one of the side streets and away from the excitement and, of course, the batons. But at every point that I tried to breach there was a sturdy posse of police in possession to drive us back into O’Connell. St, and worst luck for some, into the line of fire of the police batons.[8]

Returning strikers learned with horror of the police action on O’Connell Street and the following two days saw some of the most intense violence of the strike. For Prendergast, ‘ Returning home in the evening, I heard stories of the scenes that had been enacted in O’Connell St. on that afternoon. Larkin was true to his boast that he would be in O’Connell St. dead or alive. The following day’s paper gave lurid sensational accounts of the day’s proceedings. That day became known as “Bloody Sunday” among the working class’[9]

According to Larkin’s son (also James):

Sunday, August 30th [31st in fact], was a day of bloody and prolonged terrorism, commencing with the batoning of thousands in O’Connell Street by the members or the Dublin Metropolitan Police, assisted by hundreds of R.I.C. men specially imported into the city and made drunk for the brutal campaign. But the workers fought back, with stones, bottles, hurleys and their bare fists, and on the Inchicore tram line so fierce was the battle that soldiers of the West Kent Regiment were finally called out.

In the three days from the 30th August to the 1st September no less than thirty battles took place between the workers and the police. It was out of these battles and turmoil that the Irish Citizen Army was born, when workers carrying hurleys marched alongside their bands and processions or stood round their meetings as protection against the vicious police attacks. [10]

Estimates of the casualties from the weekend’s rioting ranged from 450 up to 600. Two trade unionists John Byrne and James Nolan were beaten to death. There may also have been further fatal injuries. According to Seamus Kavanagh, a member of the Fianna, ‘One of our Fianna boys, Patsy O’Connor, got a smack of a baton on the head, as a result of which he died subsequently’.[11]

That night police, allegedly drunk and certainly out for revenge, broke into the tenements at Corporation buildings, in the north inner city where many strikers lived and where the police had been driven off the night before, smashing what few possessions the residents there had, including the ubiquitous religious statues and icons. [12]

A newspaper photographer happened to be on O’Connell Street during Sunday’s baton charge. His famous picture of the police scattering the crowd immediately made headlines far beyond Ireland. One of the places it reached with the following day’s newspapers was the conference of the British Trade Union Congress, who, outraged at the treatment of Dublin workers, and urged on by a delegation from the Irish unions pledged financial support to the strikers.

By September 2, The Irish Times was reporting; ‘Prospect of a Serious Struggle’. They were right. Already by then, 6,000 men were involved in the dispute.[13] By late September some 20,000 men and women in Dublin city and County were either on strike or locked out. The scene was set for the most famous and most bitter strike in modern Irish history.

References

[1] Padraig Yeates, Lockout, Dublin 1913, p61-65

[2] Gary Holohan Bureau of Military History (BMH) WS 308

[3] Yeates Lockout, p48-49

[4] Yeates Lockout p52-56

[5] Gary Holohan BMH WS 308

[6] Yeates Lockout p45

[7] Ernie O’Malley On Another Man’s Wound p27-28

[8] Stephen Prendergast, BMH WS 755

[9] Stephen Prendergast, BMH WS 755

[10] James Larkin Jr. BMH WS 904

[11] Seamus Kavanagh BMH 1670

[12] Yeates, Lockout p72

[13] Irish Times, September 2, 1913