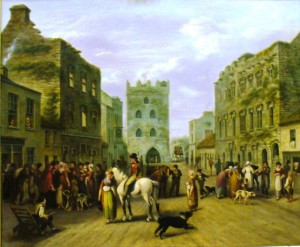

James Fitzgerald at Kilmallock – The Protestant Reformation fails in Ireland

Kilmallock 1600. An episode of the failure of the Protestant Reformation in Ireland. By John Dorney

In the summer of 1600, at the height of the Nine Years War, an English military party accompanied by Miler McGrath, the Protestant Bishop of Cashel and Master Job Clarke of the Council of State, made their way into the town of Kilmallock in county Limerick.

With them was sickly young man of 30, James Fitzgerald. He was the son of the last Earl of Desmond, Gerald Fitzgerald, who had been killed in 1580, after rebelling against the encroachment of the English state into Munster– ending some 400 years of Fitzgerald or Geraldine power in southern Ireland.

In 1600 there were two rival Earls of Desmond – James Fitzthomas Ftizgerald, backed by Hugh O’Neill and James Fitzgerald, ‘the Tower Earl’ backed by the English

James Fitzgerald had been ten at time of his father’s death in the Desmond Rebellion and had spent 16 years in the Towerof London. He was slight and in perpetual poor health, but he had one advantage for the government, he had been brought up in England and was a Protestant.

Since October 1598, there had been a rebel Earl of Desmond, committed to the war of Hugh O’Neill against the English and Protestant dominance in Ireland; James FitzThomas Fitzgerald, derided by his enemies as the Súgán (‘straw rope’ ie fake) Earl.

The Annals of the Four Masters record that,

‘As the country was left in the power of the Irish on this occasion, they conferred the title of Earl of Desmond, by the authority of O’Neill, upon James, the son of Thomas Roe, son of James, son of John, son of the Earl; and in the course of seventeen days they left not, within the length or breadth of the country of the Geraldines … which the Saxons had well cultivated and filled with habitations and various wealth, a single son of a Saxon whom they did not either kill or expel. Nor did they leave, within this time, a single head residence, castle, or one sod of Geraldine territory, which they did not put into the possession of the Earl of Desmond, excepting only Castlemaine’.[1]

In order to try to win back the support of the Fitzgeralds’ kin and dependants, George Carew, the Lord President of Munster took James, the son of the Earl from the Tower and re-introduced him as a new, loyal Earl of Desmond.

It was a bold and somewhat desperate move. The English Undertakers or colonists, who had possessed themselves of confiscated Geraldine land were not impressed, fearing, “that in after times he might be restored to his Fathers Inheritances, and thereby become their Lord, and their rents (now paid to the Crowne) would in time be conferred upon him”.[2]

At the crisis point of the Nine Years’ War, George Carew was prepared to disregard them in the interests of the state.

‘A trial of dispositions and affections’

But first, as with a modern marketing campaign, Carew had to test his audience’s response. His secretary, Thomas Stafford, recorded, “For the President to make trial of the disposition and affection of the young Earl’s kindred and Followers, at his desire consented that he should make a Journey from Moyalla into the County of Limerick. And to Master Boyle his Lordship gave secret charge, as well to observe the Earl’s ways and carriage, as what men of quality or others made their address unto him ; and with what respects and behaviour they carried themselves towards the Earle, who came to Kilmallock upon a Saturday in the Evening.”[3]

James Fitzgerald seemed to offer peace and stability so at first was ecstatically welcomed in Kilmallock

At first, the new Earl seemed wildly popular. The townspeople of Kilmallock flocked to catch a glimpse of him,

“all the Streets, Doors and Windows, yea the very Gutters and tops of the Houses were so filled with them, as if they came to see him, whom God had sent to bee that Comfort and Delight, their souls and hearts most desired, and they welcomed him with all the expressions and signs of love, every one throwing upon him Wheat and Salt; an ancient Ceremony used in that Province, upon the Election of their new Majors and Officers, as a prediction of future peace and plenty.”

Like a modern day celebrity, James Fitzgerald was mobbed everywhere he went in the town. When he went for supper to the house of one George Thornton,

“The Earl had a Guard of Soldiers, which made Lane from his lodgings to Sir George Thornton’s House, yet the confluence of people that flocked thither to see him was so great, as in half an hour he could not make his passage through the crowd; and after Supper he had the like encounters at his return to his lodging.”[4]

Why was James Fitzgerald so popular in a province where he had not been since he was a child? One reason was that FitzThomas, the rebel Earl, was widely seen as an upstart. James was clearly the legitimate heir to the Desmond title, and in early modern society such things mattered.

But also, the people of Kilmallock must have pined for some peace and stability. In 1570, during the first Desmond rebellion, James Fitzmaurice Fitzgerald had burned Kilmallock, making it, ‘an abode of wolves”. John Perrot, the Lord President of Munster claimed that no one could walk in safety a mile outside the town for fear of the Geraldine guerrillas.[5]

No one wanted a repeat of those dark days.

But the late 16th century also saw a Catholic religious re-awakening in the Munster towns, in which the population increasingly refused to conform to the established Protestant Church of the English Kingdom of Ireland.

Between 1593 and 1595 the size of congregations attending the Protestant services at Cork Cathedral fell from over 1,000 to less than 10 people. Protestant Christenings, marriages and burials services in the city also dried up in the same years. The early 1590s also saw the founding of Irish seminaries in Catholic Europe at Salamanca, Lisbon and Douai. [6]

According to Sir John Dowdall who fought as an officer of foot in Munster, (writing in 1595) they, “do transport them [priests] from Spain to Ireland and from Ireland to Spain again, and likewise to France which swarm up and down the whole country, seducing the people and the best sorts, to draw them from God and their allegiance to the Prince”.[7]

The Munster towns were the site of a Catholic re-awakening in the 1590s

Kilmallock even had its own martyr. In 1579, the Lord President Drury had hanged Patrick O’Healy, Catholic Bishop of Mayo in Kilmallock on a charge of treason.[8]

‘Loud and Rude Dehortations’

So the big test for James Fitzgerald’s popularity came on Sunday, the day after he arrived in Kilmallock. Thomas Stafford recalled with dismay,

“The next day being Sunday, the Earl went to Church to hear divine Service ; and all the way his Country people used loud and rude dehortations to keep him from Church; unto which he lent a deaf ear; thus after Service and the Sermon was ended, the Earl coming forth of the church, was railed at, & spat upon by those that before his going to Church were so desirous to see and salute him.”

When Fitzgerald went to the Protestant service in Kilmallock on Sunday, his popularity evaporated

It was obvious that Carew’s experiment in introducing a Protestant Earl of Desmond was a failure.

“After that public expression of his Religion, the Towne was cleared of that multitude of strangers, and the Earl from thenceforward, might walk as quietly and freely in the Towne, as little in effect followed or regarded as any other private Gentleman.”

The conclusions, to Thomas Stafford at least, were obvious;

“This true relation I the rather make, that all men may observe how hateful our Religion and the professors thereof, are to the ruder and ignorant sort of people in that Kingdom: For from thence forward none of his Fathers followers, (except some few of the meaner sort of Free-holders) resorted unto him ; … But the truth is, his Religion, being a Protestant, was the only cause that has bred this coyness in them all : for if he had been a Romish Catholic, the hearts and knees of all degrees in the Province would have bowed unto him.”

And so, being without supporters in Munster, James Fitzgerald, known to contemporaries as the ‘Tower Earl’, was discarded as an instrument of English policy. He returned to London, where he died, penniless in 1601.

Winning the war, losing the peace

The English won the Nine Years War. Munster, in particular had been somewhat lukewarm towards Hugh O’Neill’s campaign for, as he put it, “the great questions of the nation’s liberty and of religion”.[9]

But, in so far as the state was Protestant and it required its subjects to conform to this religion, the English lost the peace.

It was not that Catholics in late 16th century Ireland were particularly pious in the conventional sense. In fact Catholic clerical observers were not that impressed with piety in Ireland.

Father Fitzsimon, a Jesuit operating in Ireland, expressed this in 1598 in a letter to Claudio Aquaviva, the General of the Jesuits, “Religion does not strike firm roots here; people by a kind of general propensity, follow more the name, than the reality, of the Catholic Faith and thus are borne to and fro by the winds of edicts and threats”.[10] But it seems clear that by this time most of Ireland’s indigenous communities, both Gaelic and Old English, regarded themselves as committed Catholics and moreover, were hostile to Protestantism.

In 1603, not long after O’Neill’s final surrender at Mellifont, the Old English towns of Munster, including Waterford, Cork and Limerick, rebelled against the state’s religious policies. They expelled Protestant ministers, imprisoned English officials, and seized the municipal arsenals, demanding freedom of worship for Catholics.

They refused to admit English commander Mountjoy’s army when he marched south, citing their ancient charters from 12th century. Mountjoy retorted that he would, “cut King John his charter with King James his sword”, and arrested the ringleaders, ending the revolt.

The effect of the episode though, was to show just how estranged the Old English Irish towns had become from the Protestant state.

As James, the Tower Earl, might have told his English sponsors, the battle for religious affiliation in the south of Ireland had been won by the counter reformation. In an age when states and monarchs felt they could not tolerate dissenting religions among their subjects, it was an ominous sign for the English in Ireland in coming century. [11]

References

[1] Annals of the Four Master pp 2082-2083

[2] PacataHibernia p 165

[3] Pacata Hibernia p 163-164

[4] Ibid.

[5] Colm Lennopn Sixteenth CenturyIreland, The Unfinished Conquest, p 215

[6] Padraig Lenihan, ConsolidatingConquest,Ireland 1603-1727

[7] Maxwell, Constantia, Irish History From Contemporary Sources (1509 – 1610), George Allen & Unwin Ltd., London 1923, p146.

[8] Lennon p 316

[9] McCarthy Daniel The Letter Book ofFlorence MacCarthy Reagh, Tanist of Carberry, p227

[10] P Maxwell, 150

[11] John McCavitt, The Flight of the Earls, p53