‘Without Law or Justice’: Class conflict in the Irish border counties 1920-23.

How social strife accompanied the Irish revolution in the north midlands region. By John Dorney.

At a meeting of evicted tenants at Cavan Town Hall in 1923 a Mr MacAbhareagh (McAvery) Chairman, told his listeners, ‘We need to recover the land from which our fathers and grandfathers were thrown off without law or justice’. He called for the division of ‘ranches’ and an end to the ‘system which makes Ireland a market garden for England’. [1]

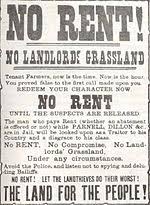

Many expected the Irish nationalist revolution to finish off the ‘land wars’ of the late 19th century, expropriate the remaining landlords and give ‘the land to the people’. In December 1921, all across the region ‘unpurchased tenants’ went on rent strike, demanding that the new [Provisional] Irish government buy out their landlords.

Nor was land the only social issue that caused violent conflict. The following year there were bitter strikes in the area, not between landlords and tenant farmers, but between farmers and their labourers. Shots were exchanged between them until finally the Army of the new Irish Free State settle matters in the farmers’ favour.

As state authority broke down in rural Ireland in 1920-21, a raft of social conflicts, both land and labour disputes, took on a violent intensity

On June 10, 1922 at a Labour meeting, Lyons, a Labour party candidate in the upcoming election declared that; Workers, ‘should have the advantages of education and to hold his own with the sons of the capitalists.’ He ‘stands by the principles of James Connolly and Jim Larkin. (Cheers) The great are only great because we are on our knees, let us arise’.[2]

These are not isolated examples. As state authority broke down in rural Ireland in 1920-21, undermined by both the political and military campaigns of the republican movement, a raft of social conflicts, some long dormant, some appearing for the first time, took on a violent intensity.

At the same time, class conflict in all its forms was sharpened when the boom years of the First World War for Irish farmers were followed with a savage recession from early 1921 onwards. With less ground to give on all sides, violence became more and more frequently used.

In the border region in particular, the land question also had particular sectarian and communal undertones, because so much of it had been traditionally owned by Protestants, now a minority in a predominantly Catholic and nationalist region, but a majority just over the new border in Northern Ireland.

Finally the re-imposition of ‘order’ by the forces of the Irish Free State in 1922-23 in the region tells us a great deal about the society and politics of the new Irish state.

It is often written that the Irish revolution had little or nothing to do with social class. Or conversely, some socialist accounts will have it that the period was a social revolution that was aborted at its birth by the counter-revolution of the Civil War. This article will argue that neither of these positions is quite right. The overthrow of British rule was not a class movement. The republicans were not disguised social revolutionaries and the Civil War was not a class war.

But class and class conflict, in complex ways, was an integral part of the turmoil of the period as it was experienced on the ground.

Farmers and landlords

The area in question – the counties of Louth, Longford, Cavan, Monaghan and Leitrim had a combined population of roughly 450,000 in 1911.[3] Though it had a number of fairly large towns, notably Dundalk – a working port – and market towns like Cavan, Monaghan and Clones, it was predominantly rural.

Most of the commerce in the towns also depended on agriculture, principally on the sale and export of foodstuffs and animals. The local authorities also depended disproportionately on farmers’ rates, giving them a powerful political voice.

As late as the 1880s, the region had been dominated socially and politically by the classic Anglo-Irish (usually Protestant) Landlords. ‘The land for the people’ was longstanding nationalist slogan since the 1880s. And indeed, a series of Land Acts brought in by the British government in response to land agitation or the ‘Land War’, culminating in the 1908 Wyndham Act, had greatly undermined the old landed class’s position. Many had voluntarily sold their holding to their tenants, who were subsidised by the British government to do so, with long term loans.

The old landlord class were still not a completely spent force in the north midlands and south Ulster region by the 1920s

The old landlord class were still not a completely spent force in the region by the 1920s however. Many had refused to sell up, or had received too low an offer. Agrarian activists estimated that there were 2,500 ‘unpurchased tenants’ in County Cavan alone, in 1922 who had been ’wronged and robbed by landlords’ and estimated that there were 100,000 unpurchased tenants in prospective Irish Free State[4].

A look at rent disputes in late 1921 for instance shows that, many estates were still held by largely Protestant landlord families, often with close ties to the British military officer corps, who often elsewhere, with their estate managed by agents. For instance the Portland estate in County Monaghan was owned by a Captain Maxwell and managed by his agent McNorris Croddard. Similarly Major Purdon owned the Purdon estate in County Cavan and the Logan Ellis Estate in Bawnboy was also possessed by an old style landlord family and managed by agents Ross Todd and Co. based in Dublin.[5]

So the demand for the end of ‘landlordism’ and for tenant purchase – which was still seen by nationalists as reversal of the ‘conquest of Ireland’ was still a live issue during the independence struggle.

That said, the land struggle had meant that by the 1920s, the stronger, more prosperous farmers had mostly been freed from paying rent and tensions rose between them and small farmers and the landless.

Though it had zones of good land, the region was mostly too hilly and boggy for extensive tillage agriculture and by far the most profitable activity was raising live cattle for export. This meant that inevitably big farmers tried to consolidate their holdings into larger ‘ranches’ while smaller farmers tried to hold on to or expand their family holdings.

These tensions had already led to one period of intense agitation – the so-called ‘Ranch War’ of 1906-1909, in which small farmers or landless men had driven away the ‘ranchers’ offending cattle and re-divided holdings until evicted by the police. A great deal of untapped bitterness and personal grudges lay dormant in the region after decades of land struggles.

The collapse of British state power would bring both of these land struggles; landlord vs tenant and small farmer vs ‘rancher’ to a violent head.

Labourers

The weakness of an economy based on cattle export and small farms was two-fold. Firstly it did not supply enough jobs and secondly it often did not supply enough food, at least, not enough locally, at prices that the poor could afford.

Famine scares occurred periodically after bad harvests. It also left agricultural workers disproportionately dependent on casual labour and thus condemned to poor pay and conditions.

Famine scares occurred periodically after bad harvests. Agricultural workers were dependent on insecure casual labour

A peculiar feature of this in the whole of Ulster was the ‘hiring fair’ where on market days, young agricultural labourers would hire themselves out for six months to farmers.

To give a typical example, in November, 1921, there was a Hiring fair, at Ballybay, Monaghan. Applicants, who would line up in the market square to be inspected for their physical fitness, were informed that, ‘term time starts now’ and were offered six month contracts as servants or labourers, but were warned that as result of declining agricultural prices, ‘Wages will fall substantially’ from the previous year. The following were the wages on offer for a six month deal.

Ploughman £14-16

Farm hand, £10-12

Girl, £8-13

Boy ‘half time’.[6]

These were not terribly out of line with the national average for unskilled work. By David Fitzpatrick’s estimate, unskilled workers in Ireland expect to make an average of £25 a year in 1911, but prices of food had doubled since that time.[7].

During the years of the Irish political revolution in 1918-23, the workers’ movement also emerged as force to be reckoned with – particularly in the form of the ITGWU trade union. They fought for union recognition, regular contracts and to defend wage levels. In some cases they dreamed too of a new ‘Workers’ Republic’.

The years of the First World War (1914-1918) and up to late 1920, saw a great surge in farmers’ profits as Britain imported more and more food from Ireland, with other trade routes cut off. But the years from 1921 to 1923 saw a slump as demand in Britain dried up completion resumed from other suppliers such as Canada. In this context farmers and other employers made a concerted effort to drive down wages of their workers.

By 1922 and 1923 (the years of the civil war) when combined with bad harvests and disruption caused by political upheaval and guerrilla warfare, levels of destitution across the region had reached crisis point. Independent reports warned of acute malnutrition among small farmers and labourers, reporting that they were ‘living hand to mouth’. Every drop in prices affects their daily fare’, and that their ‘Lack of nourishing diet’ had made them ‘Incapable of sustained physical effort made by people past generations’.[8] In Leitrim there were dire warnings of imminent famine.[9]

This, as well as the unions’ attempt to regularise casual labour, resulted in some of the bitterest labour disputes of the period across the region, many of which were ultimately ended by force, state or otherwise.

The political context – rival monopolies of force

None of the above conditions would probably have caused the levels of violence and disruption that they did had it not been for the concurrent nationalist revolution.

After their victory in the 1918 election Sinn Fein rapidly set about undermining the British institutions of state, setting up their own courts (the Dáil Courts) and police – usually members of the Irish Volunteers (soon known as the Irish Republican Army or IRA) to replace the existing courts and the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC).

Frederick Engels once wrote that the state essentially exists to prevent class warfare,

‘it became necessary to have a power, seemingly standing above society, that would alleviate the conflict and keep it within the bounds of ‘order’ …. This public power exists in every state; it consists not merely of armed men but also of material adjuncts, prisons, and institutions of coercion ….”.[10]

If the state and its instruments of coercion are supposed to ‘keep conflict within the bounds of order’, what happens when there are two or more rival ‘bodies of armed men’ trying to do this in the same place at the same time?

In fact, the rival attempts of the British and republican systems to impose their own ‘monopoly of force’ meant that law and order began to break down altogether. A coordinated IRA action crippled the ability of the RIC to police rural areas effectively. On Easter weekend 114 rural RIC Barracks were burnt across the country by the IRA, including those at Baileboro, Standone, Crosskeys (partially) in Cavan, five more in County Longford, 9 in Meath, 2 in Leitrim and 3 in Fermanagh. Several more were later destroyed in Monaghan. Income tax records were also destroyed.

Law and Disorder

From early 1920 there were frequent complaints in the region of a rise in crime. The proliferation of lethal weapons also did not help matters. In March 1920 Cavan Assizes (courts) warned that crime was up because of the ‘impunity’ with which burglars can operate and the widespread use of revolvers in robberies.[11]

There were a series of murders in the region that may or may not have been related to the political conflict. In November 1919, for example, a father and son, Farrelly were arrested for the murder of Thomas Carroll in November 1919 at Eighter, Co. Cavan. The motive was apparently a land dispute but the deceased was also accused of being an informer. On April 17, a farmer, Francis Curran, (66) was shot dead at Carrigallen, Monaghan, the motive was again unknown.[12]

The normal policing and courts system collapsed in the face of of Republican insurgency after 1919 leading to both a rise in crime and in violent land disputes.

Sinn Fein and the IRA aspired to keep ‘order’ themselves and their courts and police – styled the Irish Republican Police, in effect competed with the Royal Irish Constabulary. For instance, after the murder of another farmer Mark Clinton, who was shot dead, apparently in a land dispute, in May 1920 in County Meath, 6 men were later arrested , two by the RIC and 4 by the IRA.[13]

By August the ‘Sinn Fein Courts’ were up and running. At Cootehill, for example, one Bernard McDonald was convicted of assault and threatening language towards his neighbour in a land dispute and fined.[14]

Some locals responded to the upsurge in crime by forming vigilante groups. Notices signed ‘Rory of the Hills’ [a traditional name used for clandestine land agitators] were posted in Ballyconnell, county Cavan threatening ‘death to burglars’ if stolen money was not returned.[15]

But the biggest obstacle to the republicans keeping order was that the British forces, both police and military, tried systematically to dismantle their efforts. One of the first IRA Volunteers to be killed in the region was James Cogan of Oldcastle County Meath who was shot dead by British soldiers while escorting prisoners whom the IRA had arrested for cattle stealing.[16]

By September the Dáil Courts were suppressed all across the country by British forces. The Courts staff were arrested and their documents seized. At Carrigallen and Arva for example, joint British Army and RIC raids smashed in the doors with hatchets and seized their documentation.[17]

The re-assertion of British state authority did little to help the law and order situation however. With an active guerrilla insurgency underway across the region, the RIC could devote little time to fighting ‘ordinary’ crime. Indeed in many cases, state forces were perpetrators of crime.

The Auxiliary Division in particular often robbed households they were supposedly raiding for IRA suspects. The Ryan family of Leitrim, for instance were later awarded £103 for having been robbed at gunpoint by Auxiliary policemen. Michael Flynn of Annaghbradigan was beaten by Auxiliaries, who also took £96 from his home. Thomas Moran, a vintner was robbed and threatened at gunpoint and robbed of £25.[18]

And yet another source of mayhem came from the newly formed Ulster Special Constabulary – the unionist-dominated, armed, auxiliary police of Northern Ireland, formed in July 1920. In January 1921 the RIC shot dead a Special Constable, McCullough of Belfast, in Clones as he and 15 other ‘Specials’ were looting the premises of J O’Reilly’s Off License, another was wounded and the rest arrested.[19]

After the truce of July 1921, the republicans again made a concerted attempt to re-establish their own Republican Courts. Austin Stack the Dáil Minister of Home Affairs wrote to local IRA commander and TD Paul Galligan on September 26 to impress on him the importance of re-establishing the courts[20]

The justice of the Irish Republican Police was often rough and ready – tying a youth to the railings of the Cathedral in Cavan town, for instance, to shame him for petty crime. And they also faced competition from the still functioning RIC even after the Truce. There were several instances where the RIC arrested IRA or IRP personnel carrying out policing duties and some cases where both the IRP and the RIC arrested different people for the same crime.[21] Dáil Courts at Castleblayney and Lisnaskea were also broken up and their officers arrested.[22]

New states

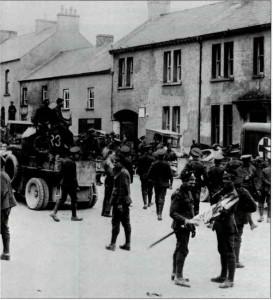

It was only after the signing of the Anglo-Irish Treaty that the British forces first withdrew to barracks and then in a process from February to April 1922 withdrew from the region altogether and Irish forces took their place. From early 1922 there now also existed a ‘hard border’ running through the region for the first time, with the IRA in possession of the southern side and the Ulster Special Constabulary on the other in Northern Ireland.

By this time though, the IRA had split over the Treaty into antagonistic factions. The Provisional Government set up under the Treaty actually reconstituted the old courts system (replacing the revolutionary Dáil Courts) in early 1922 in an effort to quell growing social disorder. But in the subsequent period of Civil War between pro and anti-Treaty factions there was very little effective law and order from any source.

Personal land disputes often ended in violence, sometimes with the intervention of undisciplined local IRA members.

In January 1922, for instance, a farmer Patrick Conlon, 59 years old, the owner of 20 acres in County Meath, who was described in the local press a ‘most respectable man’ was shot dead by armed raiders.[23] On February 11, 1922, at Carrickmacross, Monaghan, the farm of James Shelvin was seized by a Thomas Daly on behalf of his deceased father. Shelvin went to the newly installed IRA garrison in Carrickmacross, who arrested an IRA officer, Thomas Duffy for the illegal land seizure and imprisoned him in the barracks.[24]

The legacy of decades of land agitation had left a poisonous tangle of local disputes over land, which, in the border zone in 1922, sometimes had a sectarian tinge.

The legacy of decades of land agitation had left a poisonous tangle of local disputes over land, which, in the lawless conditions of 1922-23, often exploded into violence. Sometimes, though by no means always, in the border zone, this had a sectarian tinge. In April 1922 for instance, before the onset of Civil War, 20 armed men evicted a Protestant family, the Elkins, in favour of a Catholic one, the McMahons, who had been evicted from the holding 65 years previously.[25]

There was also the added social pressure caused by Catholic refugees from the violence in Northern Ireland, who sometimes pressured the IRA into displacing Protestant farmers to accommodate the northern refugees. In May 1922, three refugees from Belfast were convicted of intimidating Protestant farmer, Robert Crawford, who they told to ‘go back to the six counties’.[26]

During the Civil War, which broke out in late June 1922, between pro and ant-Treaty factions, the problem of social disorder only got worse.

According to (pro-Treaty) National Army Intelligence, a major part of the local ‘Irregulars’ or anti-Treaty IRA, appeal lay in their taking sides with evicted or otherwise aggrieved farmers in land disputes. Citing a case in November 1922 in which ’17 armed Irregulars’ visited a farmer named Byrne in Cavan and forced him to sign over his land to one of their supporters, the Army concluded, ‘The Irregulars are taking advantage of the present state of the country to annex a farm for one of their supporters’.[27]

The Anglo Celt newspaper noted that people were trying to reclaim land ‘where their fathers were evicted’. ‘As soon as normal conditions are restored in the country it is hoped to introduce new land legislation under which genuine evicted tenants will receive special consideration’.[28]

The Civic Guard (later Garda Siochana) police were introduced into the area in September 1922 but, being unarmed, were all but helpless against republican guerrillas, armed robbers and other armed bands until well after the Civil War was over. What order there was, was mainly imposed by the Army. The Pro-Treaty National Army in mid 1923 deployed a unit known as the Special Infantry Corps which to the region at the end of the Civil War to deal with social disorder. A National Army report of the summer of 1923 stated that the Special Infantry Corps was ‘having a very bad effect on the civil population in most districts where it is stationed’.[29]

It was against this background – a four year period where no one group was capable of establishing its own law and authority in the region that class conflict took on such intensity.

‘The Land for the People’

At first, it seemed as if the ‘new land war’ that accompanied the nationalist revolution, would pass the north midlands region by.

An editorial in the Anglo Celt said that land agitation was confined for now to the west; counties Clare, Kerry, Roscommon, Westmeath and was cautious in endorsing it:

‘Many claims to land are frivolous and unjust. When the fight is won, the Dail will make every effort to see that justice is done. No citizen will have to leave these shores in search of his livelihood.’[30]

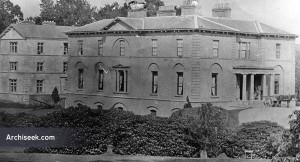

The spring and summer of 1921 saw a wave of ‘Big House burnings’ – that is destruction of landlord’s mansions, in the region. Among the mansions gutted by fire were Gola House in County Monaghan, Ravensdale House County Louth, Lanesboro House County Cavan and Shanton House at Ballybay County Monaghan. In this case, however it was the IRA that was behind the arson attacks and the motivation appears to have been to deny the Big Houses ad garrisons for British troops, rather than to settle land or rent disputes.[31]

It was only during the lapse in hostilities, after the truce of July 11, 1921, that land agitation really took off in the region.

After the truce and Treaty of 1921, there was a concerted rent strike by tenant farmers across the north midland region.

Late 1921 saw a revolt of farmers all across the north midlands who had not purchased their land in previous Land Acts. It began on the Portland Estate of one Captain Maxwell in Monaghan in November, where tenants declared that with agricultural prices down by 50%, they were demanding an 85% reduction of rents and warned of ‘defensive action’ if their offer was rejected or there was any attempt to collect rent.

In late December, rent strikes spread to three more landed estates: in Bawnboy Cavan, on the Logan Ellis Estate – tenants demanded a reduction in rent to 10s and the same on the Montgomery Estate. On the Rothwell Estate, they demanded a reduction of 5s. On the Purdon estate (owned by Major Purdon), they demand that rent be cut by 8s.[32]

While initially these appear to have been militant tactics designed to lower rent at a time of falling incomes for farmers, after the Anglo-Irish Treaty was signed on December 6, 1921, and with an independent Irish government in prospect, the strikes rapidly became a tactic to force the remaining landlords to sell up.

On the Coolamber estate in Longford for instance, owned by a Mr Stanley. Tenants declared that they had tried to buy their holdings since 1908, without success. But, they stated, ‘times and conditions have altered in Ireland…We cannot raise our offer without bringing obloquy for ourselves and being unjust to other tenants. We do not consider that you have made any sincere effort to give us the benefits of the Land Acts. We are the only tenants in Longford still paying rent to a landlord’. They resolved that no rent would be paid until purchase is agreed.[33]

While the same farmers’ unions voted motions to approve the passing of the Treaty, it was also clear that they expected Irish independence to mean the end of landlordism. They argued, ‘Each person should get an equal chance in a free Ireland to compete for a decent living at least’, and called on the Dail to, ‘make completion of land purchase the first act of the Irish parliament’. ‘In future when the country is flourishing we will also have to look into land for labourers and town tenants’. ’[34] Copies of the resolution were sent to local Sinn Fein TDs Paul Galligan, Sean Milroy and Arthur Griffith.

By late February 1922 the rent strike had spread to dozens of estates across Monaghan Longford and Cavan.[35]

The pressure on landlords, particularly if they had been outspoken unionists increased in this period in which the IRA and republicans generally were left in control of much of the countryside. The Mountray estate, in Monaghan, for example was put up for sale in February 1922 after the violent re-instating of evicted tenants. One Thomas McKenna, for instance, was shot in arm when he tried to buy land off evicted tenants.[36]

At the Farnham estate on County Cavan, the tenants resolved not to pay and back rent and stated that Lord Franham had, ‘declared war on the tenants’. At the Ballyhoe estate, in Monaghan, the landlord Colonel Murray refused an offer by the Tenants association one year’s rent as a purchase price. He was informed, ‘There won’t be another’.

Tenant farmers expected the new Irish government to buy out the remaining landlords and resolved to pay not rent until this was done.

Rent strikes in pursuit of land purchase were also declare on the Maxwell, Harman and Mongomery estates. At the latter, Tenants resolved to pay no rent until purchase was agreed, and cited the ‘collapse of cattle agricultural prices’. ‘It is humanly impossible to pay the excessive rent demanded’.[37]

On April 13, the tenants association, representing all the unpurchased tenants of Cavan, representing nine estates and 2,500 families, declared, ‘This is not a case for the courts, we won’t meet the landlords there’. ‘By our resolution we will stand or fall together’.[38] In a nationwide conference held in Dublin on April 19, which claimed to represent 100,000 tenant farmers nationwide, the tenants resolved that the new Irish government must complete compulsory land purchase and that in in the meantime they would not pay any rents in arrears. The Cavan delegation declared ‘We have been wronged and robbed by landlords’.[39]

Patrick Hogan, the Provisional government Minister for Agriculture replied that he wanted to meet the farmers and that he sympathised with their grievances, but the the infant Irish state could not afford another land act; ‘Land purchase is essential for the prosperity of the agricultural industry. It is the first thing that must be done’. But, ‘the government needs £3-4 million a year [to pay for it] and it does not have it’.[40]

Fighting the Civil War, after June 1922, distracted the Free State government from land reform and most other issues until well into the following year. By then, however, it was apparent, in the border region and elsewhere, that providing an orderly means of land reform was the only way of ending much of the endemic violence across the country and to reassert government control.

Free State military forces were still being used to collect unpaid rates, debts and even rents. From February 1923, the Special Infantry Corps was raised and deployed to areas where farms had been illegally seized by the IRA and others, particularly in the west and in County Cork, to restore them to their owners. Cattle that had been grazing on occupied land were seized by the troops and sold off in Dublin. In Roscommon the Free State troops fired over the heads of a crowd trying to prevent the impounding of animals.[41]

On February 10 1923 at Shercock Cavan, a landlord sued 55 tenants for non-payment of rent, the judge, the newly established Free State courts suggest that the tenants, due to the ‘bad times’ should pay 70% of the rent due.[42]

However, as the government knew, collecting rents for landlords was a most hazardous thing for a nationalist government to do. A meeting of unpurchased tenants in Ballybay, Monaghan – 100 delegates, representing farmers on rent strike since early 1922 – heard that the troops and police had been used to collect landlords’ rent. One Father Maguire declared, that while shouldn’t be ‘armed resistance’, it was ‘terrible for government to lift money for absentee landlords who never spend a penny in the country’. [43]

Some such landlords caved in to popular pressure. In April 1923, for instance in County Cavan, Lord Farnham agreed to sell to his tenants. Others though waited to see what action the new Irish government would take in the aftermath of the Civil War.

Mollifying the small farming class, the bedrock of pro-Treaty support, was necessary for the survival of the pro-Treatyites, especially as they had called a general election for August of 1923.

In June the Agriculture Minister Patrick Hogan tabled a Land Bill under which 70,000 tenancies, containing about 300,000 people, with a rental value of £800,000-£1 million would be compulsorily purchased from the remaining landlords.[44]

This was not a redistribution of land as many agrarian radicals had hoped for, rather it simply meant that farmer would be freed from paying rent on his existing plot. Undoubtedly this land act however did help to shore up support for the Free State. Anti-Treaty Republicans such as Patrick Smith in Cavan criticised the Act as it had tenants pay 70% of back rents. He declared in a rally in Cavan town, ‘Tenants have to pay 70% of rent due’… A real government of the people by the people would say to the landlords, “you never owned the land of Ireland, you have no right to it. The land belongs to the people of Ireland”.[45]

Similarly the Labour candidate in that election argued that, ‘the land is not being well used… ‘Ranches should be broken up and divided among the people’[46]

However, by their own lights, the conservative pro-Treatyites had not only settled the national question but the land question as well. And most of those who owned land probably agreed with them.

The Workers against the farmers

However, not everyone saw the end of the Irish independence struggle in simply land for the farmers. In August of 1921, Huston, an organiser for the Irish Transport and General Workers Union (ITGWU) told a public meeting in Cavan town; ‘Workers should not vote for farmers or landlords. ‘The farmers will not pay a living wage’. We want public services controlled directly, absolutely by the people, for the people’.[47]

As early as January 1920, farmers in Cavan proposed to set up ‘Freedom Force’ following the proposal of Farmers Union branch in Enniscorthy, Co Wexford, to fight strikers. By January 28 of 1922, with the Treaty signed and British state forces withdrawing from the territory of the new Free State, some farmers were warning of all-out class warfare with their labourers. Houses had been burned they reported and produce burnt by ‘disorderly labour, hooligans’.

A 1922 Monaghan Farmers’ Union report of labour trouble stated that – ‘The farmer goes to work with a revolver in one hand for the time to come’.

A Monaghan Farmers’ Union report of labour trouble stated that – ‘The farmer goes to work with a revolver in one hand for the time to come’. A Priest, Fr Murphy warned that ‘Farmers may have to fight labour’ and urged the government to ‘put down a firm hand’.[48]

This was not empty rhetoric, as many strikes ended in violence. On August 5 1922 for instance, at Anny, Co. Monaghan, a Farmers Union member James McGinnity was shot dead during a labour dispute with his labourers. On September 9 1922 a farmer was stabbed by a worker with a pitchfork at Shercock, Co Cavan. And on February 3 1923, during strike at Arva quarry, 40 men paraded with farm implements for self defence.

Though this militancy was sometimes put down to the influence of radical agitators, in fact, as the local newspaper editorial argued, labour militancy was the result of acute hunger and hardship. Wages, which had been falling since 1921, were insufficient to buy bread and farmers were selling the best meat to England. ‘No one expects farmers to be philanthropists but why can’t farmers union in each district kill a certain number of sheep, cows and bulls and sell them at the right prices? They would have ample meat at a reasonable price.’[49]

Meanwhile the local ITGWU branch in Ballyconnell, Co Cavan proposed radical land reform that went well beyond land purchase by tenant farmers. They proposed; breaking up of grazing ranches between ‘cottiers, landless men and men who fought for Ireland in the late war [i.e. IRA men]’. They also wanted ‘direct labour on the roads’ that is for labourers working on the roads to be directly employed, rather than hired by contractors.[50]

Unlike the huge strikes of agricultural labourers in Counties Kildare and Waterford in 1923, which were put down by battalions of government troops in the Special Infantry Corps, there was no spectacular end to the strike wave in the north midlands. Rather, after the deployment of Special Infantry troops to police strikes and the establishment of police barracks, the violence around strikes gradually fizzled out by mid 1923.

The workers did not always lose these disputes. In Baileboro, Cavan for instance, workers successfully resisted an attempted to cut their wages to 24 shillings a week with wages eventually being set at 33 shillings a week for labourers, Gangers at 40s a week and carters’ wages were settled at 12 s per day.[51]

Aftermath

In the election of August 1923, although the wounds of the Civil War were still extremely raw, there was also a straightforward dimension of class conflict in the positions of Labour Party and the Farmers Party in the region. The former called for ‘Employment for the unemployed. Houses for the homeless. Land for the landless’. Patrick Sheridan, the Cavan Labour candidate stated; ‘He stands for the ideals of James Connolly. He is a Cavan man. He is a worker’.

While the Farmers Party called for ‘state loans to small farmers. Oppose ‘unreasonable interference with farmers’. ‘Oppose nationalisation in all its forms’. Reduce rates’. [52]

Meanwhile the ruling pro-Treaty Cumann na nGaedheal party did not address class issues at all in its manifesto stating its priorities were; ‘Establish National Finance and Education on a sound footing. Restore the national language. Complete the organisation of National Defence. Demobilise surplus forces. Secure Citizens against return to terrorism and violence.’

In truth, except for the land question, the Irish revolution settled little of a social nature.

The anti-Treaty Republicans denied they were on the side of radical labour and appealed almost solely to unfulfilled nationalist goals, betrayed in their eyes by the pro-Treatyites, ‘We are not against the farmer or the labourer we are in no way antagonistic to their claims. We stand for complete independence not of 26 but of 32 counties. No foreign constitution, no foreign king’.[53]

In truth, except for the land question, the Irish revolution settled little of a social nature. Workers had won the right to organise but much of their organisation, especially in rural areas was in disarray by 1923. Under the Free State there was to be no wholesale redistribution of land, as some had wanted. The ‘ranches’ so deplored by agrarian activist were mainstays of the Free State’s economy.

Wages for agricultural labourers remained low and the distress of the unemployed or small farmer was largely eased only by large scale emigration. For all that there was no desire for further armed revolution. The Farmers Party pleaded for ‘No more jail and bullet’ while Labour declared, ‘The spade produces, the gun does not, muzzle the guns![54]

References

[1] Anglo Celt November 23 1922

[2] Anglo Celt June 10, 1922

[3] Population figures are taken from the 1911 census, online here.

[4] Anglo Celt April 21 1922

[5] Anglo Celt November 25, December 31, 1921

[6] Anglo Celt November 13, 1921

[7] https://www.irishexaminer.com/viewpoints/analysis/cost-of-living-rose-in-1916-as-price-of-great-war-was-felt-by-irish-people-376678.html

[8] Based on the report of an Agricultural Commission to County Cavan, reported in Anglo Celt, March 24, 1922,

[9] Anglo Celt, April 22, 1922. One June 24 of that year, farmers in distress in Leitrim appealed to the new Irish government for ‘food and provisions’ to prevent hunger. Ibid, June 24, 1922

[10] Frederick Engels (‘The Origins of Private Property the Family and the State’, 1884)

[11] Anglo Celt march 13 1920

[12] Anglo Celt March 13 and April 17, 1920

[13] Anglo Celt May 1920

[14] Anglo Celt August 14, 1920

[15] Anglo Celt May 29 1920

[16] Anglo Celt July 27, 1920

[17] Anglo Celt September 25 1920

[18] The Anglo Celt, Report of compensation hearings at Carrickonshannon, January 21, 1922

[19] Anglo Celt January 29, 1921

[20] Peter Paul Galligan Collection [CD 105], Military Archives, Cathal Brugha Barracks, Dublin 6.

[21] Anglo Celt November 17, 1921 for instance IRP arrested youths for drunkenness at Carrickmacross fair. The RIC arrested them Francis Keenan, Peter Corrigan. Dispute between DI Mansel and IRP officer Lonergan, IRA Liason officer called. The two Volunteers were charged with false imprisonment.

[22] Ibid and Anglo Celt November 26, 1921

[23] Anglo Celt January 27 1922

[24] Anglo Celt February 11,1922

[25] Anglo Celt April 29, 1922

[26] Anglo Celt May 12 1922

[27] National Army Reports, Eastern Command, cw/ops/07/01

[28] Anglo Celt October 28, 1922

[29] National Army Dublin Command Intelligence Report Number 16 cw/ops/07/16

[30] Anglo Celt May 22, 1920

[31] Further details are in John Dorney, The Burning of Big Houses Revisited, The Irish Story.

[32] Anglo Celt December 24, 1921

[33] Anglo Celt December 31, 1921

[34] Anglo Celt, December 24 1921 and January 3 1922

[35] Anglo Celt, November 1921–March 1922

[36] Anglo Celt February 4, 1922

[37] Anglo Celt February 11, 1922

[38] Anglo Celt April 13, 1922S

[39] Anglo Celt April 19 1922

[40] Ibid.

[41] Dooley, the Land for the People, p51

[42] Anglo Celt 10 February 1923

[43] Anglo Celt March 17 1923

[44] Anglo Celt June 2, 1923

[45] Anglo Celt August 18, 1922

[46] Ibid.

[47] Anglo Celt August 13 1921

[48] Anglo Celt January 28 1922

[49] Ibid.

[50] Anglo Celt February 25 1922

[51] Anglo Celt April 14, 1922

[52] Anglo Celt August 11, 1923

[53] Ibid. In the elections itself In Cavan the Farmers Party candidate, Baxter topped the poll, followed by the Republican Patrick Smith and the former unionist JJ Cole came third. Transfers were enough to get Cumann na nGaedheal candidate Sean Milroy over the line while Sheridan the Labour candidate, polled well but finished fourth. In Monaghan, Ernest Blythe of Cumann na nGaedhel topped the poll, followed by Dr McCarvill,e a Republican and another pro-Treatyite Pat Duffy.

[54] Anglo Celt May 12, 1923, August 18, 1923