‘To get up an anti-Fenian society in this country’: Ribbonism and republicanism in Ulster, 1850-1867.

Rival forms of popular Irish nationalism in 19th century Ulster. By Kerron Ó Luain

Founded in Dublin and New York on St. Patrick’s Day in 1858, the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB) left an enduring legacy. Shortly after its establishment its members came to be known as Fenians to both their supporters and detractors, and the ‘bold Fenian men’ are familiar to most readers of Irish history.

During the mid-nineteenth century the Fenians were a secular, Irish republican, conspiratorial movement who vowed to oppose British rule in Ireland by force of arms and who drew inspiration from the republicanism of the United States, France and from their United Irish antecedents of the 1790s.

Yet, what is less widely known is that in Ulster, when Fenians in that province began their organising and recruitment efforts in the 1860s, there already existed a not entirely dissimilar nationalist conspiratorial culture – whose practitioners sometimes double-jobbed as agrarian conspirators or agents of local Catholic defence – known as Ribbonism.

The Fenians were secular and Republican, while the Ribbonmen were Catholic and conspiratorial in character.

The head of the British Army in Ireland, Sir Hugh Rose, distinguished these two movements in the following manner in 1865:

‘Ribbonism is not too strong, separated as it is, to some degree from Fenianism – The one is of pure Irish, a religious growth, the other is of Irish origin, but tinged with Americanism, free thinking or free acting, and not subject to religious discipline and control.’[1]

While Rose over-emphasised the lack of clerical influence on the Fenian rank-and-file, he was correct in his analysis of Ribbonism as having been fervently Catholic in character; a fact borne out by its evolution into the conservative, clericalist Ancient Order of Hibernians (AOH) organisation later on in the nineteenth century.

At the behest of ‘Wee’ Joe Devlin of the Irish Parliamentary Party, the AOH, at the turn of the twentieth century, represented a formidable opposition to the IRB. But what were the mid-nineteenth century origins of this rivalry? And was the relationship between these two varieties of nationalism defined entirely by perpetual and outright hostility, or were there some surprising overlaps which have up till now had little light shed upon them?

Ribbonism’s origins

The Ribbon societies were Catholic secret associations that emerged during the nineteenth century and were strongest in North Leinster, North Connacht and Ulster. They were hierarchical in nature and centred on a Ribbon lodge whose place of meeting was often the local public house. The use of the term ‘Ribbon’ originated in the habit of Ulster’s faction fighters sporting ribbons to distinguish opposing combatants.

The Ribbon societies were Catholic secret associations that emerged to oppose ‘Orangeism’ during the nineteenth century and were strongest in North Leinster, North Connacht and Ulster.

The Ribbonmen’s primary outlook was anti-Orangeism; by extension they were infused with Catholic nationalist ideology which manifested in processions on religious feast days such as St. Patrick’s Day (17 March) and the Feast of the Assumption, or Lady Day (15 August), as well as in clashes with the Orange Order during the summer marching season. Within the Ribbon mentality the folk memory of dispossession intertwined with a militant, though sometimes ill-defined, Catholic nationalism and vestiges of 1790s Republicanism.[2]

Indeed, Ribbonism emerged from the culture and framework of the Defenderism of the late eighteenth century and as Tom Garvin has asserted ‘the old Defender net appears to have been reconstructed’ in the early nineteenth century when in 1816 delegates met in Carrickmacross, County Monaghan, and ‘agreed to set up a revived Defenderism’.[3]

Ribbon passwords found in Carrickonshannon in 1857 harked back to United Irish and Defender times and contained the line ‘they should remember 98’.[4] Above all, however, Ribbonism carried forward a sense of grievance towards Protestant ascendency and English governance and its networks of correspondence and association persevered for the greater part of the nineteenth century.

Between the 1860s and the 1880s Ribbonism – heavily influenced by developments in Irish emigrant communities abroad – evolved into the more open and public Hibernianism. The Ancient Order of Hibernians (AOH) shared the obsession for marching which the Ribbonmen had and utilised all the signs, symbols, regalia and ideology Ribbonism had displayed for a large part of the nineteenth century.

But the AOH was distinguished from Ribbonism by its attempt to locate itself in middle-class, ‘respectable’ society (while drawing on working-class support) and receive the approval of both government and the Catholic Church – both of which it managed to secure by the early twentieth century, both in Ireland and overseas. In the process of its absorption and evolution into Hibernianism and the Irish Parliamentary Party, Ribbonism cast off much of its conspiratorial baggage and became more forthrightly involved in mainstream party politics and electioneering.

In the two decades following the Great Famine of 1845-50, Ribbonism was mostly composed of small traders (especially publicans) and other lower middle class occupations in the towns, while small to middling farmers and agricultural labourers predominated in rural areas.

By the end of the nineteenth century, the Ribbonmen began to abandon plans for violent insurrection and become absorbed into the Ancient Order of Hibernians – a Catholic adjunct to the Irish Parliamentary Party.

The financial situation of its leaders was often quite comfortable, which led to accusations of self-enrichment from some quarters. Ribbonism was a fraternity of the politically and economically disenfranchised centred on the province of Ulster. The northern province was polarised on sectarian lines and religion often blocked social advancement for Catholics. Consequently, Ribbonism offered a leadership clique of ambitious Catholic men, outside of mainstream Protestant society, the opportunity to gain local standing as they ascended the society’s hierarchy.[5]

Its rank and file also valued the economic and social standing it bestowed upon them. Ribbonmen achieved this by acting as arbiters in trade disputes and by enforcing protectionist policies in local markets.[6]

They also facilitated emigration to Britain during the pre-Famine period for economic reasons, or if the Constabulary needed to be evaded, while unemployment benefit and funeral expenses were provided to members too. The key to receiving these benefits and being a part of the system which conferred them were the quarterly passwords, or as Ribbonmen termed them; ‘the goods’.[7]

The nature of post-Famine Ribbonism

The Great Famine accelerated the shift in Ribbonism away from being an insurrectionary body and towards becoming a benefit network. Ribbonmen had entertained notions of national rebellion up until the early 1840s, but after the leaders who advocated this were transported such plans were shelved.[8]

The Ribbonmen became in part a Catholic benefit society and in part a protection racket, extorting money from non-members.

By the 1850s and 1860s Ribbonism acted primarily as a mutual-aid and associational network, with centres of activity on the Ulster borderlands of South Armagh and around East Donegal especially where strong links were maintained with the industrial hubs of Scotland and Northern England.[9]

Along with this move away from rebellion came a drift towards respectability. Some Ribbonmen, when seized with what government would have alleged were ‘seditious’ documents during this period, bemusedly questioned the constabulary as to what the harm was in having them.[10] Magistrates, moreover, sometimes prevaricated over prosecuting Ribbonmen as the documents sometimes lacked any content that could be deemed seditious.

Elsewhere, common criminality, intimidatory practices and conspiracy prevailed. In Sligo in 1853, Michael ‘Captain’ Conlon, apparently a Ribbon lodge master, attempted to coerce Thomas McGarry into joining the Ribbon society by forcing him into paying a shilling and threatening that he could not leave the house in which they were drinking ‘until you treat me’, to which McGarry refused, whereupon Conlon physically assaulted him.[11]

Such association with the murky criminal underworld, and Ribbonism’s innate secrecy, earned the condemnation of the Catholic Church. Bishop of Down and Connor, Cornelius Denvir, writing to the Vatican in 1855, optimistically claimed he and his clergy had succeeded in persuading many Ribbonmen away from the networks during the early 1850s to the point that they had almost disappeared.[12]

Despite the selfish, secretive and criminal tendencies so despised by the clergy, Ribbon associational activity, crucially, occurred within an Irish nationalist context, and the Ribbon networks were not friendly societies in the same sense as their apolitical British counterparts examined by E. P. Thompson.[13]

Ribbonism and Catholic defence

Ribbonmen also continued in their role as defenders of the Catholic population in the face of Orange aggression into the post-Famine years, and so remained active in the communal riots which frequently broke out in Ulster during this period.

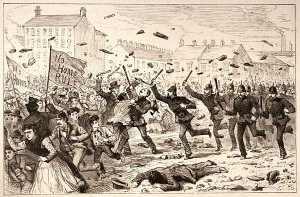

The most serious of these riots occurred in Belfast during 1857 and 1864, and there were hints of organised Ribbon activity among the Catholic crowds during both outbreaks.

The riots of 1857 saw the majority Protestant Sandy Row district square off against the majority Catholic Pound district, after tensions arising from the Orange Order’s Twelfth of July parades and inflammatory sermons by Protestant firebrand preacher Revered Thomas Drew. This sparked rioting for nearly a week, in July and again in August after more anti-Catholic preaching by Protestant evangelists such as Orange Order member Hugh Hanna.[14]

During bloody riots in Belfast in the 1850s and 60s, Ribbonmen were rumoured to have organised the defence of Catholic neighbourhoods.

Defence of the Catholic Pound district demonstrated some organization. In the midst of the violence a Catholic Gun Club – accused by the Tory press of having been a Ribbon creation – was formed and one historian, Mark Doyle, has hypothesised that Ribbonmen formed an ‘organisational skeleton’ among Catholic rioters during 1857 due to the co-ordinated nature of the rioting from within the Pound community.[15]

There was further suggestion of Ribbon involvement in the rioting of August 1864, sparked by Protestant objections to a delegation of Belfast Catholics travelling to Dublin to attend the laying of the foundation stone on nationalist and Catholic leader Daniel O’Connell’s statue on the main street of that city. On their return, Sandy Row Protestants burned an effigy of the ‘Liberator’ and deposited its ashes in a coffin. The next day about 2,000 Protestants marched in procession at a mock funeral for O’Connell. Widespread rioting followed which lasted ten days and at least eleven deaths and 300 injuries were recorded as a result of the violence, which spread throughout much of Belfast.[16]

At least one report during the 1864 clashes in the metropolis noted that the Belfast Ribbonmen requested the assistance of their north Connacht brethren. Stipendiary magistrate P. C. Howley wrote from Sligo to inform Under-Secretary Thomas Larcom that he had heard:

from a reliable source that a communication has been made by the Ribbonmen of Belfast to their brethren in this town and county requesting their co-operation and aid in that city at the present juncture, and consequently many persons have left here privately with a view of taking party with their co-religionists.[17]

The Ribbon networks and agrarian crime

The phase of Ribbonism emerging from the shadows occurred primarily in the last quarter of the nineteenth century, and Foy has argued that 1872, the year in which the Party Processions Act of 1850 was repealed, marked a turning point as Ribbonmen could march in Ulster without being impeded by the police.[18] But in both the early 1850s around South Armagh and in the late 1850s and into the early 1860s in Donegal, Ribbonism was involved in conspiratorial agrarian violence.

Ribbon members in reality, bore more similarities to a protection network similar to the mafia than an agrarian secret society, like the Whiteboys of a previous generation.

Ribbonism’s links to agrarian violence – especially after the Famine – are often misinterpreted. The two phenomena are not always inherently intertwined as is often believed. Kelly has concluded that Ribbonmen attacked those who transgressed the land code not to redress a wrong felt by the wider peasant community, but instead to mete out retribution where individual Ribbon members had been slighted and thus, in reality, bore more similarities to a protection network similar to the mafia than an agrarian secret society.[19]

Despite this important finding having been made over a decade ago, many historians continue to portray Ribbonism as simply another in a long series of agrarian secret societies in the vein of the Whiteboys, but with some politico-religious vestiges.

The detection of these Ribbon agrarian crimes often occurred due to an increased surveillance by the police during phases where landlord-tenant conflict was most marked. As a result of the agrarian unrest of the early 1850s Ribbon lodges were detected in urban Dundalk in 1849 and in Drogheda, Belfast and Randalstown, Co. Antrim in 1851 and Downpatrick, Co. Down in 1852. In 1853 a number of other lodges were broken up which uncovered a network stretching from Slane, Co. Meath, to Mohill, Co. Leitrim, and back across South Ulster towards Monaghan and Louth.[20]

In the wake of these arrests, a series of Ribbon trials were held in which Hugh Masterson and another man named Gerald Farrell gave testimony. In one such trial in Dundalk it came to light that £70 had been collected to help the killers of a land agent named Robert Lindsay Maulever emigrate during 1851 and that the lodge in question had continued to meet regularly in the town up until August 1853.[21]

In places like Mid-Ulster, where pressure for land was not as intense as in South Ulster, and in urban Belfast where land conflict was obviously not a feature, countering Orangeism was the main Ribbon pre-occupation, outside of its primary function of association and mutual-aid. But on the Ulster borderlands where population density was high, lodges in towns such as Dundalk and villages such as Crossmaglen became involved in the agrarian struggles of the countryside.[22]

Ribbonism abroad

Because of its role in facilitating emigration and supporting migrants as a mutual-aid society Ribbonism became more prominent in industrial England and Scotland as the outflow of people leaving Ireland’s shores increased.

The Ribbonmen had a presence in both England and America.

It was reported by one Head Constable that there were three to four thousand Ribbonmen in Manchester in 1854, [23] far above the 700 estimate provided by Doyle for Belfast Ribbon society members during the same decade.[24]

By the 1850s and 1860s in the US, Ribbonism’s offshoot, the AOH, attended St. Patrick’s Day demonstrations and church consecrations in their thousands, and held annual conventions with delegates from Divisions across the Union.[25]

During 1855 in Sligo town a father and son, surnames Marron, were suspected of being Ribbonmen and of propagating the network in the area. Second Head Constable Lowe believed that Marron’s son, amongst many others, had returned from America to busy themselves in spreading the system in the county.[26] Lowe had picked up on a phenomena of crucial importance to not just Ribbonism, but also Fenianism later.

Reports of returned emigrants suspected of propagating Ribbonism and Fenianism reached the Castle from places like Cavan and Westmeath towards the close of the 1850s. But as early as 1854 Under-Secretary Thomas Larcom had received information, in which the sentiment rather than the detail was more important, that ‘over 20,000 men from all the States are already enrolled and ready at a moment’s notice, to take advantage of the slightest embarrassment of the Government, by means of the approaching European Wars, to sail for the invasion of Ireland’.

Though Ribbonism was not serious about sending a naval expedition of Irish-American soldiers from the US to Ireland in the way the embryonic Fenian Brotherhood was in the mid-1850s, much of the impetus for Ribbon re-organisation between and the 1850s and 1880s – and its consequent transition into Hibernianism – emanated from the US and Britain where large numbers of Irish Catholics had settled and had their nationalist views reinforced by their experience of exile in the wake of the Great Famine.

Carrying forward nationalist sentiment

Although Irish Ribbonism was not as robust as its outgrowths in other corners of the globe, vibrant Ribbon networks persisted in the northern half of Ireland into the late 1850s and onwards through the 1860s.

In some parts of Ulster these provided fertile ground for Fenian ideas, while in other areas of the province Ribbonism’s already existing associational culture and staunchly Catholic ethos provided a formidable obstacle for republican emissaries.

The years 1856 and 1857 were relatively quiet in terms of Ribbon networks and activity being uncovered by the police. The agrarian struggles of the early 1850s had ended, but Phoenix Society and IRB organisation had not yet begun in earnest in Ulster and the constabulary do not appear to have been as focussed on detecting secret societies. Nevertheless, the sources reveal that Ribbon activity continued beneath the surface through these years.

In some parts of Ulster Ribbonism provided fertile ground for Fenian ideas, while in other areas of the province Ribbonism’s staunchly Catholic ethos provided a formidable obstacle for republican emissaries.

On 7 October 1856 the police entered the backroom of a public house in Ballinamore, County Leitrim, where they found seven men. On the floor near the men were the following passwords:

What is your opinion of England and France?

They will have war at first chance

The French are angry, you see it plain

Because of raised rebellion in Spain

The clouds are changeable

So the Church of England

May France and England disagree

And by the aid of America we will be free.

Such sentiments show that England’s difficulty being Ireland’s opportunity was not a concept confined to the Fenian leaders. Similar ideas existed within the lower-class nationalism of Ribbonism. Whether they emanated from there or were adopted is another question and further research on the continuity of such thought between the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries is certainly warranted.

Towards the end of 1857 more passwords were discovered in Ballinamore. They contained the usual strong nationalist flavour, this time alluding to Daniel O’Connell. Passwords nearly identical to these were found on Patrick Duffy in Belfast in 1858 and later on Thomas Healy in the village of Leitrim in 1859.[27] Thus Belfast and the west of Ireland continued to be linked by Ribbon networks right up to the end of the decade.

In the 1860s when the re-emergence of republicanism in Ulster was driven by the Fenian movement, the ambiguity of Ribbon politics – at once harking back to the United Irishmen of 1798, yet at the same time sectarian – allowed for some organisational and philosophical fluidity between the two strains of nationalism.

1858: enter the republicans?

In Ireland and America during the 1850s various republican organisations began to organise towards the objective of overthrowing British rule in Ireland through the use of physical force.

The US-based Emmet Monument Association funded Joseph Denieffe to carry out efforts to recruit in Ulster from 1856, while Jeremiah O’Donovan Rossa established the Phoenix National and Literary Societies in the south-west of Ireland the same year.

These strands were amalgamated into the IRB, or Fenian movement, upon its foundation in 1858 and from then on the Trans-Atlantic relationship in Irish republicanism was crucial in terms of manpower (and womanpower in the form of the Fenian Sisterhood), in the transmission of ideas, and in financing the build-up towards potential rebellion in Ireland.

The Irish Republican or Fenian Brotherhood was founded in 1858 but at first found it difficult to make inroads into Ulster.

The US-based Clan na Gael, for instance, which was particularly active from the 1870s onwards, through the years of the Land War of 1879-82 and into the revolutionary period of 1913-23 played no small part in the history of Ireland.

In Ulster in the mid-nineteenth century, at the close of 1858 an increase in working-class nationalist conspiratorial organisation took place in Derry City and appeared to be influence both by Ribbonism and the emergent Fenian movement. An ex-constabulary man named Michael McGawley became involved in what he believed to be Ribbonism in the city.

By March 1859 McGawley had divulged all he knew of the organisation to Sub-Inspector Thomas Kirk. Neal Gallagher, who propositioned McGawley about joining the Ribbon Society, stated that ‘it would be of benefit to him and protect him in Derry’. This was typical of other accounts of inductions into Ribbonism.

The following week the men met in Hogan’s public house where Gallagher informed McGawley that ‘his name and the Donnells were the names in this county that were destined to free this country’. They then left the public house and in the street opposite McGawley was sworn in and afterwards paid Gallagher a shilling for doing so.

McGawley reported that he had been at other lodge meetings where small urban traders predominated, and that on 2 March 1859 a meeting was to have taken place with what he described as a deputation from Inishowen. McGawley further described some of the details of the society to the Sub-Inspector:

In any conversation had with members of the society they were to use every means that could possibly be resorted to, to upset the Government of Ireland and that the Americans would assist. That Patrick Gallagher and James Joyce instructed the members that they were to provide me arms.

McGawley also recounted the oath to the Sub-Inspector, which contained clauses to ‘never be satisfied with any other but a republican [government] for the Irish nation’ and not to purchase goods from Protestants so long as they could attain such from Catholics.[28]

The above episode at first reading appears to have been a curious admixture of Ribbonism and a nascent Fenian separatism. The oath and objectives mark it as the earliest example of Fenianism in Ulster. However, other traits are typically Ribbon, most glaringly its anti-Protestant character. The sources do not tell us whether this organisation was affiliated with the IRB which had been formed in the south by Fenian leader James Stephens some six month previously, or whether it was an American Fenian import.

The IRB did not make significant gains in the north until the early 1860s. Perhaps the most likely reason for the activity in Derry were that Fenian ideas had reached the city and been adopted by the traditional bearers of lower-class nationalism there, the Ribbonmen.

Seeing as how such ideas were really only the more developed expression of the Ribbon passwords which had cropped up through the mid to late 1850s in various locations this seems a plausible explanation, although McGawley’s credibility as an ex-constabulary member ought to be questioned too.

The Belfast Ribbonmen

A Ribbon meeting broken up in Belfast towards the close of 1858 revealed that Ribbonmen who had been affected by arrests during 1851 had regrouped and a vast network of up to twenty lodges existed in the city.

As had been the case in Belfast before, their main purpose was association for economic and social benefit with the secondary purpose of countering Orangeism. But, significantly, the notion of Irish American assistance for rebellion seen in their passwords chimed well with the budding Fenian movement:

We expect a war between England and France

Yes, the Irish brigade is on the advance

Let each man fill his station

The navies are making preparation.

When the constabulary once again moved on the networks through the use of informants, Patrick Cairnes, who had acted as secretary for one of the Belfast lodges, fled to New York where he conversed with the eminent Fenian John O’Mahony. O’Mahony later wrote that:

‘The news he brings is highly encouraging. The Ribbonmen throughout the North are fully determined to join the Phoenixes, as they call them. In Belfast they have 20,000 stand of arms. Their organisation extends through all Ulster and much of Connacht and Meath.’[29]

It is not necessary to accept all of Cairnes’ claims as truthful, merely to note that as a prominent Belfast Ribbonman he was sympathetic to the budding Fenian movement.

More discoveries of Ribbonism were made in 1860 in both Dundalk and Donegal, and in Westmeath and Donegal again in 1861 and 1862. Furthermore, an elaborate network that linked Fermanagh, Armagh and Newcastle upon Tyne was uncovered in 1863 and 1864. Post-Famine Ribbon survivals, then, were to have a significant bearing on the birth of the northern IRB.

Enter the republicans proper

When Carlow native John Nolan, a key figure in northern Fenianism, entered the headquarters of the IRB in Dublin during 1862 and explained to the leadership of James Stephens and Thomas Clarke Luby that he had been propagating Fenianism in the north for some time, both men registered surprise.

This was indicative of the low priority which had been placed on spreading IRB circles in Ulster by the southern leaders in the early years. Why this was remains a mystery.

But, with the exception of Belfast where the Repeal movement of the 1840s had been strong, the more prosperous and commercialised Dublin, Munster and South Leinster regions had since O’Connell’s time been the traditional hubs of popular nationalism in the country.

Perhaps the Fenian leaders initially sought to focus their efforts in those areas where success would come more readily, rather than in Connacht which exhibited lower levels of politicisation or Ulster where Orangeism, and indeed Ribbonism, may have blocked the way.

Perhaps as a result of this oversight, the only attempt that had been made in Ulster prior to 1862 was on an individual basis by Nolan, unbeknownst to the key Dublin and Munster figures. Formal efforts appear to have been stepped up following the encounter.[30]

Afterwards, Fenianism began to register on the radar of the administration in the north. In 1863 Sir Henry John Brownrigg, Inspector General of the Irish Constabulary, noted in one of the earliest mentions of Fenianism in Ulster by officialdom that:

It must always be borne in mind, that, wherever there is Ribbonism there is an agency which may be turned to ill account at any time of excitement. Accordingly in the County of Down, Ballinahinch District, a society is said to be springing up under the name of the Fenian Brotherhood, composed of the lower class of farmers, their servants, labourers etc., all reputed ribbonmen under the guidance of a national school teacher.[31]

Frank Roney

Around the same time, an iron moulder and Fenian Head Centre for Belfast, Frank Roney, who had already built up a force of 1,000 IRB men in Belfast by 1861 after being sworn in by John Nolan, embarked upon organising missions to South Ulster where he found that Ribbonism around Armagh and Monaghan in particular was split into two factions.

The so-called ‘old’ faction was wedded to anti-Protestantism and according to Roney the ‘new’ faction (effectively a British-based Hibernian network), led by a figure named Nolan of Manchester, ‘held that religion was no bar to Irish brotherhood’. For Roney, the IRB ‘was Irish and Nation; the Ribbon society was sectarian and Catholic, and was banded to fight the Orangemen’.

Roney claimed that in Armagh he was successful in weakening and ultimately destroying the old faction of Ribbonism, the county Delegate being the last to be sworn in as a Fenian. In Monaghan, however, a conference between the ‘old’ and ‘new’ factions ended in failure when Roney and some of his Armagh IRB comrades were attacked with a barrage of ginger ale bottles on their way home.

Later on, Roney succeed in overcoming some of the animosity toward the new-fangled republican ideology in Monaghan when he won over prominent local Ribbonman James Blayney Rice to Fenianism sometime in 1862 or 1863. Rice appears to have used his local status and knowledge of pre-existing Ribbon structures to bring a not insignificant portion of Monaghan and Cavan Ribbonmen into the Fenian fold.[32]

Southern recruiters into the fray

It was not until 1864 when southern IRB emissaries made their way north in the hopes of extending recruitment into the northern province. To this end, Fenian leader O’Donovan Rossa made a number of tours of Ulster.

He encountered many of the same problems that Roney had. In the area outside Newry one group of Ribbonmen expressed opposition to the IRB after they learned that there were Protestants within their ranks. When it was explained to them that the United Irishmen Lord Edward Fitzgerald and Robert Emmet were Protestants, the Ribbonmen claimed they had been agents of the English, which provoked a row in the room and Rossa walked out.

In Cavan, Rossa was blocked by a parochial mentality when he came across some members of the Ribbon Society near Cootehill who would not be sworn into the IRB due to their suspicion of him as an outsider, rather than from any ill will towards Protestant Fenians.[33]

Fenian organisers were dismayed at the level of anti-Protestant sentiment among northern Ribbonmen, even towards United Irish heroes of 1798.

In 1865, Edward Duffy, the great organiser of northern and Connacht Fenianism, registered some success in swearing in Ribbonmen. Duffy had contacts within Donegal Ribbonism and on one occasion at a fair in Stranorlar was said to have recruited a considerable number of Ribbonmen into the IRB.[34]

Knowledge of many of these episodes of Ribbon and Fenian rivalry emanate from the personal accounts and memoirs of Fenians written many years after the events. Contemporary government and press sources are lacking in this regard in that after the onset of hysteria over the IRB threat to the British establishment (known as ‘Fenian fever’) in the run up to the rebellion of 1867, many reports began to conflate any sort of conspiratorial or nocturnal group with the IRB.

A few perceptive exceptions existed, such as the report during 1864 by The Enniskillen Mail that ‘several more arrests have recently been made in Fermanagh for what is popularly termed Fenianism, but which is probably no more than the old Ribbonism’.[35]

Ribbonmen or Fenians?

One of the most insightful series of correspondence came from County Cavan between 1866-67 where Ribbonmen at once adopted Fenian symbolism and displayed antipathy towards IRB organisational advance. In November 1866, John B. O’Reilly, a school teacher in Virginia, County Cavan, wrote to the Lord Lieutenant:

‘to offer my services to get up an anti-fenian society in this country, as I am sure I can do it to a very large extent as I am well liked in the country for miles around me, and I can lead the young men as I like’.

O’Reilly continued, ‘my lord, we had a society here called the Ballags but it is going to the bad for the want of some little help’.[36] County Inspector Patton noted that the constabulary had always looked on Reilly as being a ‘Ribbonman’ and ‘indeed his father whom he had quarrelled with . . . on one occasion tarred him with Ribbonism before the constabulary’.[37]

Not long after, on 1 January 1867, the police passed O’Reilly’s home and heard shouting and loud noise inside. ‘We are all true Irishmen, we will all free Ireland’, ‘let us sing that song by [Fenian leader] Charles J. Kickham’. The police entered as the men were about to leave and found O’Reilly, Patrick O’Reilly, John McMahon (son of a publican) and James Reilly (shoemaker).

A book with a large number of nationalist songs which the men had all joined in singing was discovered. Some of the songs included ‘The Shan van Vocht’ (an old 1798 song which foretold the salvation of Ireland by the French), ‘O’Donnell Abou’ (a song written in the mid-nineteenth century about the Nine Years War and in praise of Gaelic Chieftain, Hugh O’Donnell) and ‘Dear old Ireland’ (also a song of the mid-nineteenth century, written by constitutional nationalist T. D. Sullivan).[38]

Whether O’Reilly’s motivation in offering to assist government was financial or a means of protecting his Ribbon territory from IRB encroachment is not clear, but the presence of Fenian song and sentiment in his Ribbon lodge-cum-Fenian circle is significant as an example of the overlapping nature of Ribbon and IRB nationalism at the grassroots level during these early years.

However, away from small rural homesteads, the merger of Ribbonism and Fenianism seemed to have been most successful in the condensed urban environment of Belfast. The northern capital had been the stronghold of Ulster Fenianism from early on.

In March 1864 Terrence McCann and Patrick Lynch were arrested on a charge of Fenianism. As a result James Magee of Co. Down was also arrested and some documents found including ‘a prayer book in which was a piece of paper containing passwords, also the oath and obligation of the Fraternal Society dedicated by St Patrick’.

During the trial which followed the Belfast Newsletter stated that the facts would go to show that the men were connected with both the Fenian Brotherhood and the Ribbon Society.[39] Yet, more convincing evidence detailing the interaction of the two movements in the towns and cities remains elusive.

Better Orangemen than Ribbonmen?

The Fenian John O’Leary asserted that ‘it was easier both in 1848 and in Fenian times to make a rebel of an Orangeman than of a Ribbonman’.[40] In fact, O’Leary had exaggerated slightly. Although the Fenians certainly managed to swear in some Protestants, there is little trace of genuine Orangemen being converted to the republican cause. By contrast, the Fenians had varying levels of success in winning over Ribbon recruits in Ulster. In some places they had foundered due to the suspicion of non-members, staunch ethno-religious loyalty, conservatism and factionalism of Ribbonism.

Despite their differences, the basic nationalist ideology held by many Ribbonmen was enough to propel some towards the the more sophisticated republicanism of hte Fenians.

But elsewhere the basic nationalist ideology already held by many Ribbonmen was enough to propel some of them toward the advanced nationalism and republicanism of the Fenians, or at any rate into the IRB organisation even if they may not have fully embraced Irish republicanism on an ideological basis.

Some of the key figures of the later Easter Rising, Tan War and Civil War period of 1916-23 such as Seán Mac Diarmada, Rory O’Connor, and Liam Lynch received their elementary education in nationalism from Ribbonism’s successor organisation, the Ancient Order of Hibernians. Elsewhere, and especially in Ulster, the AOH and IRB became bitter – and often deadly – rivals. James Connolly, for instance, detested the AOH for sectarianising nationalism as he saw it, and compared the organisation to an ‘ulcer’ on the Irish body politic.

Nevertheless, due to the focus placed on its counter-revolutionary, clericalist and sectarian proclivities, the AOH, and prior to that the culture of Ribbonism from whence it sprang, has been too readily overlooked as a catalyst in moving some of its adherents towards more radical republican positions. To gain a picture of the history of republicanism in Ireland the entire milieu of nationalist culture in which it developed must also be taken into serious consideration.

Hobsbawm, in his Primitive Rebels book which appeared first in the 1960s, delineated a progression between the reactionary and inarticulate peasants and labourers of Southern Europe in the nineteenth century and more modern, progressive political formations.[41]

Though the abovementioned Tom Garvin picked up the slack in the Irish context during the 1980s, there still remains much work to be done to see if Irish republicanism had a equivalent trajectory.

References

[1] Commanding General in Ireland Sir Hugh Rose to Lord Lieutenant John Wodehouse, Curragh, 27 Aug. 1865 (Bodleian Library Oxford, Kimberley Papers, Ms Eng C 40 30, 164-7).

[2] Tom Garvin, ‘Defenders, Ribbonmen and others: underground political networks in pre-Famine Ireland’ in Past & Present, no. 96 (August 1982), pp 133-55.

[3] Tom Garvin, The evolution of Irish nationalist politics (2nd edn., Dublin, 2005), p. 42.

[4] Copy of Passwords found on Andrew Spollen, Carrickonshannon, 18 Feb. 1857 (N.A.I., CSORP 1858, 8812).

[5] Jennifer Kelly, ‘An outward looking community?: Ribbonism and popular mobilisation in Co. Leitrim 1836-1848’ (PhD thesis, Mary Immaculate College, University of Limerick, 2005), passim.

[6] Jennifer Kelly, ‘The Downfall of Hagan’: Sligo Ribbonism in 1842 (Dublin, 2008), pp 14, 25-28, 128-129.

[7] John Belchem, ‘”Freedom and Friendship to Ireland”: Ribbonism in early nineteenth-century Liverpool’ in International Review of Social History, no. 39 (1994), pp 33-56.

[8] Garvin, ‘Defenders, Ribbonmen and others’, p. 149

[9] Kerron Ó Luain, ‘The Ribbon societies of counties Louth and Armagh, 1848-1864’ in Seanchas Ard Mhacha, xxv (2014), pp 140-1.

[10] For instance, in the case of Redmond O’Hanlon, a Ribbon leader apprehended near Crossmaglen in 1864 Sub-Inspector Holmes to Inspector General, Crossmaglen, 20 April 1864 (N.A.I., CSORP 1864, 16011).

[11] RM Knox to Larcom, Tubbercurry, 9 Aug. 1853 (N.A.I., CSORP 1853, 7207).

[12] Bishop Denvir to Propaganda, 19 Nov. 1855, cited in Ambrose Macaulay, Patrick Dorrian: bishop of Down and Connor, 1865-1885 (Dublin, 1987), p. 183.

[13] E. P. Thompson, The making of the English working class (London, 1963), p. 418.

[14] Dictionary of Irish Biography (http://dib.cambridge.org) (20/08/2014).

[15] Mark Doyle, Fighting like the devil for the sake of God: Protestants, Catholics and the origins of Violence in Victorian Belfast (Manchester, 2009), pp 63, 68.

[16] Ibid., passim.

[17] RM Howley to Larcom, Sligo, 17 Aug. 1864 (N.A.I., CSORP 1864, 18255)

[18] Michael Thomas Foy, ‘The Ancient Order of Hibernians: an Irish political-religious pressure group 1884-1975’ (MA thesis, Queen’s University, Belfast, 1976), pp 10-15.

[19] Kelly, ‘Popular mobilisation’, p. 207.

[20] See for example, newspaper clipping entitled ‘County Meath Assizes’ in Sub-Inspector to Castle, 6 April 1853 (N.A.I., CSORP 1853, 3688).

[21] Belfast Newsletter, 19 Aug. 1853.

[22] Kerron Ó Luain, ‘Popular collective action in Catholic Ulster, 1848-1867 (PhD Thesis, Queen’s University Belfast, 2016), pp 58-66.

[23] Head Constable to Inspector General, Manchester, 26 April 1854 (N.A.I., CSORP 1854, 14596).

[24] Doyle, Fighting like the devil, p. 63.

[25] The Waterford News, 27 April 1860; The New York Herald, 17 March 1871.

[26] 2nd Head Constable W. R. Lowe to Sub-Inspector J. R. Gibbons, Cliffony, 3 Nov. 1855 (N.A.I., CSORP 1855, 9984).

[27] Resident magistrate H. G. Curran to Larcom, Strokestown, 21 Dec. 1857 (N.A.I., CSORP 1857, 10668).

[28] Sub-Inspector Kirk to Larcom, Buncrana, 7 March 1859 (N.A.I., CSORP 1859, 2409).

[29] Jeremiah O’Donovan Rossa, Rossa’s recollections, 1838-1898: memoirs of an Irish revolutionary, ed. Seán Ó Lúing (Connecticut, 2004), pp 302-303.

[30] Brian Griffin, ‘The Fenians in Ulster, 1858-1867’ in The Irish Sword, xxv, no. 101 (Summer, 2007), pp 281-3.

[31] Ribbonism (N.L.I, Brownrigg’s Report on the state of Ireland in the year 1863, MS 915, pp 68-9).

[32] Frank Roney, Irish rebel and California labour leader, ed. Ira B. Cross (Berkeley, 1931), pp 60, 75, 95.

[33] Seán Ó Lúing, ‘A contribution to a study of Fenianism in Breifne’ in Breifne: Journal of Cumann Seanchas Bhreifne, iii, no. 10 (1967), p. 159.

[34] Brian Mac Cafaid, ‘Fenianism and County Donegal’ in Donegal Annual, vii, no. 2 (1967), p. 142.

[35] Enniskillen Mail report carried in Belfast Newsletter, 9 April 1864.

[36] John B O’Reilly to Lord Lieutenant, 2 Nov. 1866 (N.A.I., Fenian F-files, 2322).

[37] County Inspector Patton to Inspector General, 20 Nov. 1866 (N.A.I., Fenian F-files, 2322).

[38] Constable Ruddock to Sub-Inspector, Virginia, 3 Jan. 1867 (N.A.I., Fenian F-files, 2322).

[39] Belfast Newsletter, 1 April 1864.

[40] John O’Leary, Recollections of Fenians and Fenianism, vol i (London, 1896), p. 111.

[41] E. J. Hobsbawm, Primitive rebels: studies in archaic forms of social movements in the 19th and 20th centuries (London, 1965), passim.