Film Review: No Stone Unturned

Directed by Alex Gibney

Directed by Alex Gibney

2017

Reviewer: John Dorney

This film, on limited release in Ireland, should be causing mass outrage. And yet it isn’t.

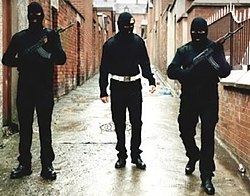

It is the story of the shocking events in a small pub in the village of Loughinisland County Down, in June 1994, when a team of gunmen from the loyalist UVF burst into a small bar, where 15 men were watching Ireland play Italy in the World Cup, fired off a full magazine from a VZ.58 rifle (a Czech derivative of the AK 47) and shot 11 men, killing six.

The men had been targeted because Loughinisland, a tiny crossroad village was largely Catholic and because those watching the Republic of Ireland team on television were assumed to be nationalists. Ostensibly, the shooting was retaliation for the INLA’s killing the previous week of three UVF commanders in Belfast.

It was, along with the Greysteel massacre and the Shankill Road bomb, one of the worst atrocities of the tail end of the Troubles. Less than two months later the Provisional IRA declared a unilateral ceasefire and the loyalists followed suit roughly two months after that. No one, despite the pledges of the then Northern Ireland Secretary Patrick Mayhew and the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) police force, was ever prosecuted.

The facts of the killings at Loughinisland are troubling enough. However, as the film shows over its two hours, still more troubling was the police response. One detective at the scene assured the widow of the pub owner Adrian Rogan, that the RUC ‘would leave no stone unturned’ in the search for the killers. As Clare Rogan acidly comments in the film, ‘they never even lifted a stone, never mind turned it.’

The film goes on to lay out a barely believable, were it not so well documented, litany of evidence, showing that elements of the RUC, in particular the Special Branch, systematically destroyed evidence relating to the killings, including the perpetrators’ car, which was abandoned in a nearby field and the interview notes of subsequent interrogations.

It turns out, according to the film, that one of the team of three killers was an informant for the RUC and that the force even had advance notice of the attack, though they did not believe it would go ahead on the night in question.

And even more shockingly, the film goes on to name the killers, one of whom it says was a serving British soldier, who still lives a short distance away from Loughinisland. It seems that his wife wrote to a local SDLP councillor naming her husband as the main shooter on June 18, 1994.

Irish libel laws are extremely strict, so this review will not repeat any of the names mentioned.

Be under no illusion, the Northern Ireland conflict was brought to an end by hundreds of dirty little compromises. Some loyalists still claim that loyalist hardliner Billy Wright ,killed by the INLA in prison in 1997, was the victim of state collusion with Republicans. Some Republicans allege that the high casualties among the IRA in Tyrone in the 1990s at the hands of British Army ambushes were the result of a deal done with high ranking Republicans to show the futility of continuing the ‘Long War’.

And whether such claims are credible or not, the ‘Dirty War’ was extremely murky. Republican Danny Morrison in this film acknowledges that the IRA officer charged with killing informers in the 1980s and 90s was in fact a British informer (a contention Republicans long denied).

Still, it is profoundly shocking to see, in this film, such open collusion on the part of the RUC with loyalists in the 1990s. All the more so, given that the targets of loyalists in this period, as at Loughinisland, were usually totally innocent of paramilitary activities.

According to one RUC detective, not Special Branch, interviewed for the film, the entire interrogation of the main suspect for the Loughinisland shootings, consisted of RUC officers encouraging him to kill a suspected IRA member, on whom they supplied details.

The suggestion here is that the RUC, and perhaps even some higher up in the British state, were hand in glove with the loyalist project to terrorise the Catholic community into calling for the IRA to call off its armed campaign. While the RUC did jail many loyalists in this period and while many police officers carried out their duties professionally, the thesis of widespread collusion with loyalists must now be given the most serious attention.

The film itself has done some remarkable research into the Loughinisland killings, though one must wonder if such open disclosure of names, dates and addresses of paramilitaries has not potentially put some innocent lives in danger.

Some minor criticisms; the historical overview of the origin of the Northern Ireland conflict is rather fuzzy, claiming that ‘Ireland declared independence in 1922 and as part of the deal, Northern Ireland remained in the United Kingdom’. Neither of which is quite true – Irish Republicans declared independence in 1919, Northern Ireland was created in 1920, the Anglo Irish Treaty of 1922 merely copper-fastened partition.

Nor does the film explain how Protestant and unionist dominance of Northern Ireland ultimately sparked the renewed conflict. This might have been helpful in explaining the composition of the RUC and how collusion with loyalists may have come about.

Also the reenactments of the shooting seem almost in bad taste. News footage might have done the job better.

Nevertheless, this film is a remarkable and unsettling piece of work. It probably should not surprise us that it took an outsider, an American, to make this film. What is a little surprising is that it is not causing a greater scandal both north and south of the border in Ireland.

But perhaps time has moved on. Perhaps both the public and the political class deem it better to let sleeping dogs lie. And perhaps it is. The RUC is gone now, replaced by the Police Service of Northern Ireland. British troops in Northern Ireland are confined to barracks. Paramilitaries on both sides have to large degree disarmed. And yet, without some kind of reckoning, the risk is that the events detailed here could some day happen again.