Weapons of the Irish Revolution Part III – The Civil War 1922-23

John Dorney wraps up a three part series with a look at the weapons of the Irish Civil War. See Part I 1914-16 here and Part II the War of Independence here.

One of the paradoxes of the Irish Civil War, fought between pro and anti-Treaty nationalist factions, was that the IRA, which a year earlier had been almost out of ammunition, was now armed to the teeth.

As a result, areas such as counties Sligo, Wexford and Kildare saw far more fighting in the civil war than in the war against the British.

A return to arms

There were several reasons for this relative abundance of arms. In the beginning, no one in the IRA thought the truce would be permanent and the leadership, including those who later accepted the Treaty, was actively preparing for a resumption of war with the British.

Due to a massive rearmament during the truce both pro and anti-Treaty factions of the IRA were much better armed at the outbreak of the Civil War than before it.

During the truce the IRA managed to import a significant amount of arms; modern Mauser rifles (not the obsolete ‘Howth’ 1871 models used in 1916 but the G98 type used by the German Army in the First World War) of which several hundred were landed at Helvick County Waterford in November 1921 and more in April 1922, along with thousands of rounds of 7.92 mm ammunition (some of it armour piercing) and more 9mm handguns – most of which were sent to IRA units in the north[1].

Collin also imported another batch of Thompson submachine guns from America.

By October 1921, Richard Mulcahy, IRA Chief of Staff estimated that the IRA arsenal was already up to 3,295 rifles, 49 Thompson sub machine-guns, 12 machine-guns, about 6,000 pistols and 15,000 shotguns. A surge of post-Truce recruitment also saw the IRA’s membership rise from about 5,500 active fighters to a (probably nominal) total of 72,363 officers and men.[2]

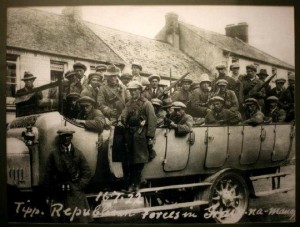

After January 1922 when the Dail accepted the Treaty and the IRA split, there were, effectively, now two rival armies seeking to fill vacuum created by the departing British. The IRA, particularly anti-Treaty elements, took advantage of the truce to seize large quantities of weapons off evacuating British forces.

In February 1922 IRA officer Ernie O’Malley took over Clonmel RIC barracks and took 600 rifles and thousands of rounds of ammunition. On March 29 an IRA unit under Sean Hegarty raided the British warship Upnor, which was docked off Cork, and got back to shore with 400 rifles, 40 machines guns, hundreds of thousands of rounds of .303 ammunition and numerous crates of high explosive[3].

And yet a third factor was that the British were committed to arming the Provisional Government’s new National Army with small arms – the standard British Lee Enfields, Lewis Guns and Webley revolvers.

A very significant amount of these arms and concordant ammunition, ended up in anti-Treaty hands – either because, like the garrisons of Waterford and Dundalk, the IRA units concerned changed sides once the Civil War broke out, or because in a murky scheme in the Spring of 1922, Michael Collins handed over British arms to anti-Treaty units in return for their passing arms to IRA units (pro and anti-Treaty) who were to attack across the new border into Northern Ireland.

Each of the four Northern IRA Divisions was to be given 500 rifles and 2-300 revolvers. Although in some cases arms failed to be delivered in these quantities and although the ‘Northern Offensive’ turned out to be something of fiasco, it seems certain a large quantity of weapons was sent north to the border in early 1922. [4]

The balance of weapons at the start of the civil war

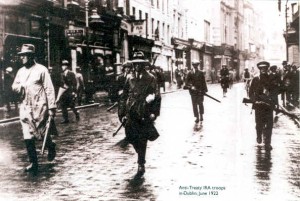

So when the Civil War broke out on June 28 1922, lack of arms was not the main problem faced by the anti-Treatyites or ‘Irregulars’. In County Limerick one guerrilla recalled ‘at Kilmallock…I saw one man with three guns…and two bandoliers of ammunition – about 1,000 rounds’[5].

IRA units in places as far apart as Cork, Sligo and Dundalk had armoured cars, rifles and machine guns in relative abundance, though they probably still did not have enough to arm their roughly 15,000 fighters. The Provisional Government at the start of the war estimated that the ‘Irregulars’ numbered about 12,900 with, between them about 6,800 rifles, as well as some machine guns and armoured cars[6].

The anti-Treaty IRA was far better armed in the war against the British but it still could not match the arsenal of Free State forces.

Their problem was of course that they still could not match the arms the British supplied to the National Army. First there was the volume of arms. Between January and June 1922, when the Pro-Treaty authorities were trying to build up an army, principally from their supporters in the IRA, the British supplied them with nearly 12,000 Lee Enfield rifles, 80 Lewis machine guns 4,000 revolvers and 3,500 grenades.

This military aid increased exponentially after the Civil War broke out and the Provisional Government set about putting down the Republican ‘diehards’. Another 27,000 rifles, 256 Lewis light machine guns and 5 Vickers heavy machine guns were donated between early July and September alone. [7] With British aid the National Army swelled to 58,000 men by the war’s close and there was no difficulty in arming them.

The key difference, however, between the two sides was artillery. At the start of the war the Free State infantry were already slightly better equipped than the anti-Treatyites, but what enabled them to drive the republicans from Dublin, Limerick, Waterford and Cork as well as many other small towns around the country in July-August 1922 was their possession of field artillery, of which the British donated 8 18 pounder field guns by 1922. The Four Courts, the republican headquarters in Dublin, a fortress-like 18th century monolith might have held out indefinitely if it had not been bombarded by four 18 pounder guns in July 1922.

Artillery decided the war’s conventional phase in favour of pro-Treaty forces.

In Limerick city similarly, had weapons been confined to small arms, fighting probably would have dragged on inconclusively for weeks in protracted fire fights in the streets. But once the Free State forces brought a single 18 pounder artillery piece to bear on the anti-Treaty headquarters in the Strand Barracks, blasting a breach in its walls, the republicans abandoned their positions throughout the city within a day.

The anti-Treaty IRA never possessed any artillery. Liam Lynch their Chief of Staff tried repeatedly to import mountain guns from Germany, but could not get either the cash or the contacts in Germany together. It is difficult to see, in any case, how they could have got past the Royal Navy blockade.[8] The result was that, with some exceptions, the IRA could not take even a well defended barracks, let alone large towns, certainly after the late autumn of 1922.

Their attempts at improvised mortars, to compensate for lack of artillery, were largely a failure. In Kerry for instance in January 1923 a strong column led by Tom McEllistrim and John Joe Sheehy attacked the National Army post in Castlemaine, trying out an improvised ‘trench mortar that fired 12-15 shells at the Army post.’

Most of the shells did not explode at all and the only one to hit the barracks did no damage, leading the Kerry Volunteers to satirically name it, ‘the 6th commandment’, thou shalt not kill’.[9]

At the start of the civil war both sides had access to armoured cars but as the conflict went on, the armoured vehicles in the anti-Treatyites’ possession either broke down or were put out of action in combat. By contrast the Pro-Treaty forces received an ongoing supply of armoured vehicles from the British, with the result that by the winter of 1922 the Free State forces also had a marked superiority in armoured vehicles and mobility.

The impact of Civil War weapons

Peter Hart made the point that the Civil War’s relatively low casualties showed that it was not the availability of weapons, but the will to kill that upped the conflict’s body count. To some extent this is true, the early battles of the civil war were characterised by a great deal of shooting and relatively low casualties.

Casualties even in quite intense civil war engagements were usually low.

For instance in July 1922 a 400 strong National Army force under Sean McEoin, complete with an 18 pounder artillery piece, re-took the village of Collooney county Sligo after a bombardment and a protracted fire-fight. The fighting lasted the better part of a day and involved hundreds of fighters firing thousands of rounds and an artillery barrage, but produced only one fatality, an anti-Treaty IRA Volunteer[10]. There are numerous examples in these early days of fighters on both sides being reluctant to shoot to kill.

And yet the fighting of July-August 1922 was still probably (except for the Rising of 1916) the bloodiest compact period of the Irish revolution, with, by my estimate about 3-400 killed in action within about 8 weeks. The widespread availability of modern weapon and ammunition did make a difference.

In Tralee for instance on August 2nd, the Free State column took the town from its Republican garrison after some hard fighting that left 9 Pro-Treaty and 2 Anti-Treaty soldiers dead with a further 20-30 Free State wounded. One well-sited Lewis machine gun, in a mill overlooking a crossroads, alone killed seven of the National Army soldiers. The Free State troops, using mortars and armoured cars eventually stormed the mill and put the Anti-Treaty fighters into retreat. [11]

The Thompson submachine gun, now in quite wide use, could be deadly at close range. At the ‘Clones Affray’, a skirmish in February 1922 between the IRA and the Ulster Special Constabulary at Clones train station, one Volunteer raked the Specials’ train carriage with his submachine gun, killing 4 and wounding 13, in the space of a few seconds.[12]

Similarly during Frank Aiken’s successful assault on Dundalk barracks in August 1922, Todd Andrews, who was there, wrote of the assault that two groups of ten men attacked the northern and southern gates of the barracks. Five in each group carried a ‘mine’ and five carried Thompsons. When the mines were exploded the machine gunners rushed into the breach and ‘silenced’ the Free State sentries.[13]

A third example is the attack on Wellington Barracks, Dublin in November 1922 when a an IRA squad of 3 men, one armed with a Thompson and a 100 round drum, the rest with handguns, on an overlooking rooftop sprayed over 100 National Army soldiers lined up on the parade square – they manage to hit 22 in just five minutes of firing, killing one and seriously injuring 14.[14]

The most effective weapons of the anti-Treaty guerrillas were automatic weapons and improvised mines.

Nevertheless, the Free State forces’ superiority in small arms and ammunition grew more and more marked and more important as the Civil War went on. In a typical engagement, such for instance at Leixlip in December 1922, National Army troops ‘suppressed’ with rifle and machine gun fire – i.e. kept stuck under cover in one place – an anti-Treaty unit and engaged them until they ran out of ammunition and then took them prisoner. The National Army detachments were often supported by Rolls Royce armoured cars mounted with Vickers belt-fed machineguns. The options for the guerrillas were either to run or surrender. [15]

Small wonder perhaps that only around 500 IRA Volunteers died in the war but as many as 12,000 were imprisoned.[16]

Weapons and ammunition could certainly be taken from Free State forces – 400 rifles and 4 Thompsons at Dundalk in August 1922 for example, along with nearly 45,000 rounds of ammunition, and 110 rifles and two Lewis guns, with 20,000 rounds in a raid on Kenmare the following month. [17]. But ammunition was difficult to replenish and by the end of the civil war many rifles were stored in dumps for lack of ammunition.

National Army seizures of weapons also greatly depleted the anti-Treaty stocks as the war went on. For instance in Dublin by the end of the war, both IRA Brigades (city and south county) could between them muster about 250 men (not all of them active) and about 50 rifles (with about 25 rounds each), 90 handguns and two Thompsons and a small amount of explosives. These were split into small dumps around the city and county. It was enough to continue a minor harassing campaign against a Dublin garrison of about 3,000 National Army troops – with 5,000 more nearby in the Curragh, but no more than that.[18]

However, there was one sense in which the National Army’s abundance both of arms and of inexperienced recruits was a mixed blessing. Their weapons safety was often appalling. For instance, out of 93 Free State personnel who died violently in Dublin city, 33 men, or over a third, died either in firearms accidents while cleaning their weapons or were shot by their own nervous or careless comrades.[19] If this pattern was repeated around the country (as seems likely), then perhaps 200 of the roughly 800 National Army and other members of the Free State forces who died in the civil war may have been the victims of firearms accidents.

Adapting guerrilla tactics in the Civil War

As the Civil War went on the IRA found that the conventional infantry weapons of rifle and light machine gun were of less and less use for their brand of guerrilla warfare. Lack of training and perhaps ruthlessness meant that IRA marksmanship was usually abysmal.

In urban areas they typically needed weapons that were easily concealable, and by the end typically they were held by women sympathisers and only carried for ‘jobs’. For instance in April 1923, in Dublin a woman named Josephine Evans was arrested at 29 Georges Place at safe house where the Active Service Unit came to collect their weapons. She had 2 ‘Peter’ [C96 Mauser] automatic pistols, 2 revolvers and one Winchester rifle with stock cut off. [20] As they had been against the British, the IRA’s urban guerrillas’ main weapon was the improvised hand grenade and the pistol.

By the end of the war the anti-Treaty IRA had lost much of its weapons and ammunition.

Even in open country the improvised explosive or ‘mine’, remotely detonated, was found to be a much better bet than the rifle. The mine, unlike the rifle, was capable of inflicting large amounts of casualties at minimal risk to the attackers. The mine probably inflicted the majority of the National Army’s dead and wounded in combat.

To take just one of many examples, in November 1922, at Carrickmacross County Monaghan, an area where the anti-Treaty guerrillas generally accomplished very little, a remotely detonated mine totally destroyed a troop lorry, killing or wounding all ten soldiers aboard at no loss to the 12 man IRA ambush party, who afterwards collected the troops’ arms and ammunition.[21]

‘Mines’ were also a staple of the IRA’s attack on fortified positions – Aiken’s attack on Dundalk is the best example but one could also instance the capture of Clifden, Connemara, in October 1922, the report of which was circulated to all IRA units as a textbook example of how to use ‘mines’.

In order to capture the three National Army barracks in the town, teams of engineers, under covering fire from rifles and Lewis guns placed petrol tin mines by the walls and detonated them via an electric cable. The Free State garrison of over 100 surrendered when the walls of the main barracks collapsed.[22] These improvised explosives were also widely used to blow up the houses and businesses of the republicans’ political enemies, particularly Senators, though simple arson was also used for this.[23]

The use of mines was considered by Free State troops to be a terror tactic, a cowardly form of warfare. The bombs could horribly mutilate a body without giving the victim any chance to fight back.

In Kerry their use unleashed the most hellish atrocities of the war in March 1923 when in reprisal for the killing of five soldiers in a booby trap bomb at Knocknagoshel, 8 IRA prisoners were tied to mine at Ballyseedy and blown up by vengeful National Army soldiers, the first of three such massacres by Free State troops in Kerry.[24]

By the end of the war Frank Aiken, by now IRA Chief of Staff (after the death of Liam Lynch), was reporting that they needed to rethink their whole way of guerrilla warfare for the future, in which explosives (the ‘mine’) and other heavy weapons would be key rather than small arms.

In a letter to Ernie O’Malley in June 1923 (after the ceasefire), he wrote, ‘if we have to fight another war against the [Free] Staters it will have to be short and sweet and our men will have to be trained in taking the offensive in large bodies… I believe the rifle and revolver is out of date as an offensive weapon and that the rifle should only be on protection for special corps of engineers. The use of explosives, gas and fire, may be concentrated on, also trench mortars’.[25]

National Army Intelligence similarly reported that by the end of the Civil War the anti-Treatyites were contemplating ‘a general mining campaign’, ‘to blow up businesses of government sympathisers’ and (in Dublin) to carry out selected assassinations in the streets.[26]

Indeed many anti-Treaty IRA operations in the Civil War involved no combat at all, whether they were assassinations of lone troops or politicians, or burning of houses or destroying of infrastructure.

In caricaturing the anti-Treaty campaign, pro-Treaty Minister Ernest Blythe said

‘It was almost magnifying it to call it a war at all. Except in one or two cases in Kerry, the Irregulars never put up a decent fight. They got behind a hedge and shot a man and came in the dead of the night burned a house. They weren’t around to fight the Black and Tans but suddenly they were great heroes… ‘Any fellow who went out with the gun and the petrol tin [for arson attacks] deserved the firing squad and none got it except who deserved it’. [27]

Did arms decide the Irish Civil War? To an extent, yes. The Free State was armed and funded by Britain and this, for better or for worse meant that the anti-Treatyites could not win a conventional military victory. However the republicans’ guerrilla campaign, which targeted the infant state’s infrastructure and economy as much as its military forces could conceivably have brought down the Treaty settlement.

That it did not was, the members of the government such as Ernest Blythe argued, down to the Cabinet’s steely use of executions and counter-terror. More widely though, as many guerrillas ruefully noted, their campaign was never as effective as the one against the British had been because it lacked the same degree of popular support.

In this sense the Free State’s superior weapons only created the necessary conditions for the republicans’ military defeat. As Eamon de Valera and the anti-Treaty leadership realised in the wake of the Civil War, it was through politics, not guerrilla warfare that republican objectives would be advanced in the future.

Conclusions

The Irish Revolution was very far from being bloodiest internal conflict or nationalist revolution to take place in the wake of the First World War. Nevertheless, weapons did matter, both symbolically and in how they were used.

‘It was almost magnifying it to call it a war at all.’ Ernest Blythe.

Combat, of relatively restrained sort though it admittedly was, also mattered. The ability to impose one’s will on a political adversary ultimately depended on it. Political violence and sabotage by itself was not enough.

But in conclusion it would not be right to present the Irish Revolution as a time of manly heroism and epic battles. It was undoubtedly at its opening driven along by the same militaristic enthusiasm that was sweeping all of Europe. But by its close most people were sick of guerrilla war and political violence.

Local candidates for respectively the Farmers’ Party and the Labour Party in the election of August 1923 made the point that most had simply had enough of armed revolution by that time. One Farmers’ Party candidate thought that it was ‘high time for the parties to this miserable dispute to settle the bloody conflict…no more jail and bullet…the people have been ground down long enough with militarism’. A Labour man thought, ‘the revolver has taken the place of the shamrock as the national emblem’, while another declared, ‘ the spade produces, the gun does not, muzzle the guns!’[28]

Frank Aiken’s decision to order the IRA to ‘dump arms’ in May 1923 marked the welcome end for most people, of the decade of the gun.

References

[1] Testimony of Pax Whelan, Waterford IRA in Uinsean MacEoin, Survivors, 1980, p114

[2] The Thompson Gun in Ireland http://thompsongunireland.com/Michael%20Collins%20TSMG.htm

[3] John Borgonovo, The Battle for Cork, July-August 1922, p21

[4] Cited in Matthew Lewis, Frank Aiken’s War, p136-137

[5] Joseph Campbell As I was Among the Captives, Joseph Campbell’s Prison Diary 1922-1923, Cork 2001

[6] Michael Hopkinson, Green Against Green, p126

[7] Hopkinson, Green Against Green p127

[8] Hopkinson, Green Against Green p236

[9] Tom Doyle, the The Civil War in Kerry p251-252, Ernie O’Malley’s interview with Tom McEllistrim in ‘The Men Will Talk to Me’ Kerry Interviews by Ernie O’Malley, p209. One Free state solider was killedin the action however. Volunteer Ferguson.

[10] Kathleen Hegarty, They Put the Flag A-Flyin’ The Roscommon Volunteers, 1916-1923, p317

[11]Niall Harrington, Kerry Landings, p130-131

[12] Anglo Celt February 18, 1922

[13] Andrews, Dublin made Me, p261-265

[14] For the IRA report on the action see Twomey papers UCD p69/77 OC IRA Dublin 1 Bde to CS and p69/29 OC Dublin 1 Bde to Ernie O’Malley. For the National Army report see Military Archive, Cathal Brugha Barracks, cw/op/07/01 The National Army thought the IRA had used a Lewis gun too and told the press there were up to 40 attackers armed with rifles and machine guns for this version see here https://www.theirishstory.com/2010/06/09/wellington-barracks-dublin-1922-a-microcosm-of-the-irish-civil-war/ But in fact the IRA reports show that their squad had only eleven men, broken up into 4 parties and only two of these did any firing (90 rounds with the Thompson and 15 with a ‘Peter’ automatic.

[15] See here https://www.theirishstory.com/2015/01/08/a-damn-good-clean-fight-the-last-stand-of-the-leixlip-flying-column/#.VRiGTfzF_To

[16] The number of anti-Treaty IRA fighters killed n the Civil War has yet to be definitely determined. The Last Post, The Republicans’ roll of honour lists about 400 names for 1922-1924. Its seems likely that this is something of an underestimate it is not clear by how much.

[17] For Dundalk attack see here https://www.theirishstory.com/2013/08/14/today-in-irish-history-august-14-1922-the-anti-treaty-ira-attack-on-dundalk/#.VV0lvblVhHw, Ernie O’Malley reported to Liam Lynch that Aiken had taken over 100,000 rounds but Aiken reported less than half that, see Twomey papers p69/29 for Kenmare, see Michael Hopkinson, Green Against Green p206-207

[18] Dublin 2 Brigade (South County) reported its inventory in May 1923 after the dump arms order. Twomey papers P69/22 Dublin 1, (city)’s inventory was reported by National Army intelligence on May 2 1923. National Army archive cw/ops/07/16. Dublin 2 was slightly better off for ammunition with 1,000 .303 rounds and around 1000 different caliber handgun rounds, while Dublin 1 (the more active Brigade) had only about 300 .303 rounds and a limited quantity of ammunition for either the handguns or the Thompsons, which both took .45 rounds but of different types.

[19] See here https://www.theirishstory.com/2012/06/19/casualties-of-the-irish-civil-war-in-dublin/#.VV0umLlVhHw

[20] National Army Civil War archive, Cathal Brugha Barracks (CW/OPS/07/03).

[21] Anglo Celt November 18 1922. Of the ten wounded soldiers the local paper reported that one, Conlon died of his wounds the day after but it seems likely there were more.

[22] Twomey papers p69/77 AG to all Brigade OCs 11/12/22

[23] See here https://www.theirishstory.com/2011/06/21/the-big-house-and-the-irish-revolution/#.VV0teLlVhHw and here https://www.theirishstory.com/2013/10/10/let-it-be-under-our-thumb-the-history-of-the-seanad/#.VV0tn7lVhHw .

[24] See here https://www.theirishstory.com/2011/03/14/march-1923-the-terror-month/ Ultimately 24 prisoners were killed in revenge fro the mine attack at Knocknagoshel, some in more ‘mine’ atrocities, others summarily shot.

[25] Anne Dolan, Cormac O’Malley Eds , No Surrender Here, Ernie O’Malley’s civil war papers p378

[26] National Army Intelligence Reports, Dublin Command 1923, CW/07/16

[27] Anglo Celt August 4 1923.

[28] As reported in the Anglo Celt May 12, 1923 and August 18 1923