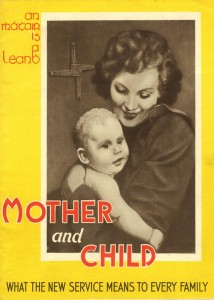

The Mother and Child Scheme – The role of Church and State.

Rhona McCord takes a fresh look at the clash of ideologies and interests in the Irish state over the Mother and Child Scheme in 1951.

The 2012 controversy arising from the tragedy of the death of a pregnant woman at Galway University Hospital was not the first time that the question of women’s health caused a controversy in Irish society. The campaign to introduce pro-choice legislation in the Republic of Ireland in 2012 bears some similarities to the attempt by Dr. Noel Browne in 1951 to introduce the famous Mother and Child scheme.

Attempts made by Irish governments between 1945-1953 to reform the health service to include health care for new mothers and their infants resulted in one of the country’s biggest controversies, subsequently known as the Mother and Child Scheme, of March/April 1951. This period was marked by what Maeve Wren described as ‘a series of titanic battles between bishops, doctors and politicians’ and ended with the quashing of the proposal.[1]

Failure to introduce the Mother and Child Scheme was due to a number of factors involving the vested interests of the I.M.A. (Irish Medical Association) and the ability of non-parliamentary lobby groups to influence government policy. The public controversy surrounding the abandonment of the scheme and the subsequent resignation of the then Minister for Health, Dr. Noel Browne is well documented and is a reflection of the weakness of Irish Governments in challenging the authority of the Catholic Church in this period.

Dr. Browne’s attempt to bring in progressive legislation to provide free maternity care was fiercely resisted by the Catholic Church and the medical profession. This article re-examines the events and poses two questions, firstly was this was a clash of Church and State or a successful intervention by the medical lobby to protect their vested interests? And secondly was this a defining moment in the decline of Catholic authority in the hearts and minds of ordinary people in the Republic of Ireland?

‘The most radical document ever produced on the Irish health service’ – Free healthcare and its opponents

The 1945 Departmental Committee on Heath Services, was set up to examine the Irish health service and make official proposals for reform. The Department of Local Government and Health, of which the Committee was part, was considered at the time to be a radical and innovative agency. In parallel with the introduction of the National Health Service in the United Kingdom, post-war Irish governments attempted to implement universal health care in the Republic of Ireland in the late 1940s and early 1950s.

The report written by the chief medical officer, Dr. James Deeney, has been described as, ‘the most radical document ever produced on the Irish health services’.[2] The report proposed the provision, on a phased basis, of a free medical service for the whole population. The scheme was to be administered by G.P.s as state-paid medical officers, mirroring the National Health Service (NHS) in the United Kingdom. The subsequent Public Health Bill, 1945, incorporated the main points of Deeney’s report. This was a blue print for medical reform in Ireland.

The year 1947 saw the establishment of a separate Department of Health with Dr. James Ryan, of Fianna Fáil, as the country’s first Minister for Health. Dr. Ryan put forward a Health Bill in 1947, which included the provision for a mother and child service, coinciding with the extension of the NHS into Northern Ireland. It was at this point that the IMA raised their objections.

Dr. Ryan was aware of the need for support from the medical profession – commenting in the Dáil after the passing of the second stage of the bill; ‘Having decided on whatever necessary changes would have to be made, a very big cog in the whole machinery would be the medical profession’. The issue of free medical care without a means test was the main bone of contention for the I.M.A. and they argued that those who were able to pay would be subsidised by the State.

Further debate in the Dáil, was covered by The Irish Times on June 11, 1947, giving a clear indication of the growing opposition from the medical establishment. Dr. T.F. O’Higgins of Fine Gael (from whom most of the opposition to the Bill came) commented, ‘the most efficient dispensary officers were working 15 hours a day already, and there were grave doubts whether they could carry out their new duties’.[3]

O’Higgins stated that ‘Every woman and every child up to 15 would become a free patient by law, and 60% to 70% of ordinary doctor’s income came from attendance on women and children.’[4]

There were also concerns about the financial implications of providing free health care. James Dillon said that the bill would ‘make it virtually impossible for young doctors to set up and start work side by side with the dispensary doctors as they did at present’.[5] At this point there were no references to the religious implications of the Public Health Bill.

Another aspect of the growing opposition to the bill was the question of socialization. The political ideology behind Aneurin Bevan’s welfare state was being referred to as ‘creeping socialism’ and for many politicians was the real issue. The Irish Medical Association would never accept the socialization of medicine, as it would have impacted negatively on their privileged position within Irish society. The idea of a no-means-test health service was always going to be rejected by the conservative forces in the country.

The opponents of free health care described it as ‘creeping socialism’.

Eamonn McKee, in a study of the Mother and Child scheme for Irish Historical Studies, argued that vested interest was at the heart of the controversy and the vested interest was primarily that of the I.M.A.[6] McKee also noted that the ‘socialisation’ argument was often applied to discredit progressive initiatives, ‘References by the Department of Finance to ‘socialisation’ were part of the usual array of arguments deployed when confronted by a major initiative involving increased outlay by the exchequer and further recruitment to the ranks of the civil service’.[7]

McKee took the argument further to suggest that the Mother and Child controversy did not represent a clash between Church and State simply because they were not fundamentally opposed, he said ‘In a Catholic country, with a government resolutely committed to its Catholicism, the perspectives of church and state are similar. To characterise the issue as one of church versus state is to ignore this and fail to see the logic not only of the lack of protest before health legislation was enacted but also its easy resolution in 1953”[8]

The Catholic Hierarchy’s position

The Catholic hierarchy did not voice any public opposition to the scheme until it came to a head during the administration of the first inter-party government (a coalition of Fine Gael, Labour, Clan na Poblachta National Labour and Clann na Talmhan, which came to power in 1948) under the leadership of Fine Gael’s John A. Costello. The inter-party government had inherited the Mother and Child scheme and none of its leading players could have predicted the trouble it would cause them. Costello as a staunch Catholic was against anything which would undermine the Church’s moral authority while most of his party colleagues were opposed to a no means test scheme.

When the idea of free health care did resurface, the Catholic hierarchy decided to write to Taoiseach John A. Costello to voice their concerns about the scheme, Costello, for unclear reasons, decided to delay in passing these concerns on to the minister for Health, Dr. Noel Browne.

The Catholic Hierarchy objected to the provision for advice on family planning, claiming this was the Church’s prerogative.

This decision created enough confusion between Browne and the Archbishop of Dublin, Dr. John Charles McQuaid, to heighten tensions between the two men. Costello compounded this by making a decision not to pass on to the bishop a memorandum written by Browne addressing the concerns raised by the Church.

McQuaid’s objections were threefold; the first concerned ‘morality’ – the scheme intended to discuss family planning with women, which McQuaid believed was the remit of the Church and that the State was not entitled or qualified to interfere in. Secondly, McQuaid rejected the increased role of the State in the life of the individual, which he described with some exaggeration as a step towards totalitarianism. Finally, in an argument that mirrored the concerns of the medical profession, he objected to the fact that the scheme proposed no means test.

The hierarchy argued against the no-means-test element of the scheme because it was, ‘not sound policy to involve the whole community on the pretext of relieving the 10% from so-called indignity of the means test’. Barrington argues that this is when the Church over-stepped its authority, ‘These objections were hardly within the sphere of the bishop’s moral authority and echoed the arguments of the medical profession in resisting Dr. Browne’s scheme’.[9]

When Noel Browne pushed ahead with the introduction of the scheme he was still largely unaware that McQuaid was still dissatisfied. Noel Browne was a new comer to party politics and a first time minister. He was a medical doctor, trained at Trinity College and had worked briefly in the NHS; he firmly believed that money should not change hands between a doctor and patient.

As a survivor of Tuberculosis he was personally inspired to tackle the issue. He allocated a significant amount of department resources into the building of sanatoria for the treatment of T.B.[10] Browne, regularly used radio as a means of communicating with the public, it was on his return from a radio interview to promote the scheme when he was handed a letter from the Archbishop. The letter communicated to him in ominous terms that the scheme as proposed by him was unacceptable to the Catholic hierarchy.[11]

Michael McInerney the author of a retrospective feature in The Irish Times in 1967 explained the hierarchy’s position ‘They felt bound to consider, however, whether the proposals were in accordance with Catholic moral teaching, and considered that the powers being taken were in direct opposition to the rights of the family and of the individual and were liable to great abuse’.[12]

The ideological issue of State control was the root of their fears. The Church feared that state power was a step towards socialism, as McInerney explained ‘The right to provide for the health of the children belonged to the parents not to the State. The State had the right to supplement not to supplant’.[13]

Browne’s response

The validity of the Church’s argument was challenged by Browne in his autobiography when he argued that, ‘The very existence of the existing free no-means-test schemes within our own social, education and health services, as well as the British N.H.S. in the North, patently gave lie to the bishop’s condemnation of the scheme’.[14]

The hierarchy argued that the mother and child scheme interfered with the Church’s social teaching on matters of family planning and that free health care in certain countries included a gynaecologist and abortion service. At a meeting with Cardinal Dalton of Armagh, Browne pointed to the contradiction of the Church’s opposition ‘The Cardinal made no attempt to answer the one crucial and pertinent question that I put to him, about the use of Aneurin Bevan’s National Health Service by Catholics in Northern Ireland’.[15]

This contradiction existed because the Church’s motive for getting involved in the conflict was not as straightforward as they would have liked people to believe. McKee argued that there was a link between the medical profession, the hierarchy and the government he suggested that it ‘was from Ely House in Dublin that such a thread emanated: the headquarters of the Knights of St. Columbanus’.[16] McKee suggests that vested interest groups in high positions conspired with the hierarchy to use the Church to derail the scheme.

The Church’s objections were intertwined with some medical vested interests in opposing the Mother and Child Scheme.

He explained ‘What brought the hierarchy into the conflict was the successful demonstration of the innate connection between the survival of private practitioners in public health and the safeguarding of Catholic morality and social teaching.’[17] It was ultimately a combination of the forces of the Church, medical profession and weak government personnel, which resulted in the derailing of the scheme and the controversial resignation of Dr. Browne.

In reality it was the combined power of the Catholic Church and the Irish Medical Association, which succeeded in blocking the Mother and Child scheme. Both parties were able to exploit the differences within the five-party-coalition. The inexperience of the government and the difficulties that arose from attempting to balance the divergent groups within the coalition proved a destabilizing factor.

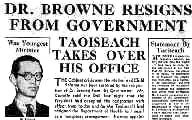

The resignation of Noel Browne

The fact that Browne could not get support from within his own cabinet made it made it impossible for him to take on the Church and the medical profession. His party leader Sean McBride knew this but made no attempt to back him. In a letter to The Irish Times in April 1951 McBride said that he had pointed out the difficulties to Browne ‘in addition to the opposition of the medical profession, he was faced with opposition from the hierarchy, the obstacles to the implementation of his proposals would be insurmountable.’

The fact that Browne could not get support from within his own cabinet made it made it impossible for him to take on the Church and the medical profession. His party leader Sean McBride knew this but made no attempt to back him. In a letter to The Irish Times in April 1951 McBride said that he had pointed out the difficulties to Browne ‘in addition to the opposition of the medical profession, he was faced with opposition from the hierarchy, the obstacles to the implementation of his proposals would be insurmountable.’

McBride was being somewhat disingenuous. As the leader of Browne’s party, Clan na Poblachta, he had stepped back from the conflict and left Browne isolated, leading to much bitterness between the two men. It was McBride himself who called for Browne’s resignation, which Browne submitted, and in doing so ignited the biggest public debate on Church-State relations since independence.

Browne felt most let down by his government colleagues and party Sean McBride.

The debate, which began in the Dáil with Browne’s resignation, soon took on a new dimension when he turned over correspondence from his department and the bishop’s house to R.M. Smyllie, the editor of The Irish Times. A total of 16 letters were handed over by Browne. Smyllie was prepared to take on the risks involved in publishing the correspondence, he is on record as saying ‘I’ll go to jail and publish’.[18]

In his resignation speech Browne did not cast blame on the Church but rather on the behaviour of his own government colleagues ‘I as a Catholic accept unequivocally and unreservedly the views of the hierarchy on this matter, I have not been able to accept the manner in which this matter has been dealt with by my former colleagues in the government’.

In the debate which followed on the 17th of April, former Clan na Poblachta TD, Peadar Cowan, took issue with the weakness of the government in allowing the Catholic Church to dictate policy; ‘The most disquieting feature of this sorry business is the revelation that the real government of the country may not in fact be exercised by the elected representatives of the people, as we believed it was, but by the Bishops, meeting secretly and enforcing their rule by means of private interviews with ministers and by documents of a secret and confidential nature sent by them to Ministers and to the Head of the alleged Government of the State. As a Catholic, I object to this usurpation of authority to the Government by the bishops’.

The legacy of the Mother and Child Scheme

The public debate following the publication of correspondence in The Irish Times raged for years afterwards and raised many questions about the role of both Church and State. The nature of the Irish State and the weakness of its democratic institutions were highlighted along with the authoritarian power of the Catholic Church in Ireland.

The controversy highlighted the sectarian nature of politics in southern Ireland. The hierarchy’s argument against public health often referred to doctors who were outside the remit of Catholic teaching. A remark by McBride referring disparagingly to Dr. Browne being photographed with a member of the Protestant clergy was particularly disturbing, a remark for which he subsequently apologised. Perhaps the most obvious point is the fact that the state, in submitting to the Catholic Church on a matter of social policy, handed the Ulster Unionists a propaganda winner, ‘Home Rule’ was indeed ‘Rome Rule.’

Noel Browne and the Mother and Child Scheme remained popular despite their failure in the 1950s.

Although a significant strand of uncompromising Catholics supported the Church’s stance on the Mother and Child scheme, most working class people did not. Over time people began to feel that they had been cheated out of a free health scheme by the interference of the Catholic Church. Ireland had one of the highest infant mortality rates in Europe at the time and a health system similar to the N.H.S would have gone some way in tackling this and other health issues associated with poverty.

Support for Noel Browne grew over generations in the poorest communities, where he became a hero, particularly for his work on the eradication of T.B. Gene Kerrigan reflects on this fact in his childhood memories, talking of the lives he saved including his aunt Eileen who survived TB, ‘A quietly committed Catholic, through the years she would never hear a word against Noel Browne, however the bishops rubbished him. He saved my life, she said, and she knew whose side he was on.’[19] Although there were only small public demonstrations supporting Browne, letters to the national and local newspapers reflected a growing animosity towards the Church and their role in derailing the scheme.

For the Catholic Church, which was already in decline, this controversy was a turning point, one incident, which in retrospect can be pointed to as the moment perhaps when they began to lose the hearts and minds of their flock. Four years later, when Archbishop McQuaid ordered his flock not to attend a friendly football match between Ireland and Yugoslavia at Dalymount Park, he was largely ignored.[20]

This was, it has to be said, primarily due of the love of the game, but never the less his authority was in decline and his role in obstructing the Mother and Child Scheme and the controversy that lingered for years afterwards played a significant role in that decline.

The late 1940s and early 1950s saw some progressive advances to Ireland’s medical services with the establishment of the Department for Health, the reduction of rates of Tuberculosis, the opening of sanatoria and a significant hospital building programme launched by Noel Browne. The idea of a free health service similar to Britain’s N.H.S was generally supported by the public but the opposition by non parliamentary and vested interest groups was too strong for the government of the day to overcome. Fianna Fáil on their return to power re introduced a watered down version of the Bill, in 1953. But the opportunity to introduce free universal health care had been lost and two-tier health system developed from then on. When the medical card was introduced in 1970 it was based on an income threshold giving effect to what Browne was opposed to, a means test.

The controversy that raged over the abandonment of Noel Browne’s no-means-test Mother and Child scheme exposed the weakness of Irish democratic institutions to assert their authority in the face of the combined power of the Catholic hierarchy and the Irish Medical Association.

The debate at that time raised serious questions about the right and ability of the Church to dictate government policy. However, unlike today’s debates on women’s health, it rarely questioned the right of the Catholic Church to dictate moral teaching. Nevertheless, the controversy that followed represented a turning point in the relationship between the bishops and their flock.

References

[1] Maeve Ann Wren, Unhealthy State, Anatomy of a Sick Society (Dublin, 2003) p. 45.

[2] Ruth Barrington, Health, Medicine and Politics in Ireland 1900-1970 (Dublin, 1987) p. 165.

[3] The Irish Times, 7 May 1947.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Eamonn McKee, ‘Church-State Relations and the Development of Irish Health Policy: The Mother and Child Scheme, 1944-53’ in Irish Historical Studies, vol. 25 no. 98 (November 1986) p.166.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Ibid, p. 186.

[9] Barrington, p. 217.

[10] For more on Dr. Noel Browne see Noel Browne Against the Tide (Dublin, 1986), John Horgan, Dictionary of Irish Biography at www.dib.cambridge.org and John Horgan Noel Browne a Passionate Outsider (Dublin, 2000).

[11] Michael McInerney, The Irish Times, 10 October 1967.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Noel Browne, Against the Tide (Dublin, 1986) p.165.

[15] Ibid. p. 169.

[16] McKee, p. 176.

[17] Ibid, p. 185.

[18] McKee, IHS p.190

[19] Gene Kerrigan, Another Country, Growing up in 50’s Ireland (Dublin, 1998) pp. 76-7.

[20] For more on this see Daire Whelan Who Stole our Game: the fall and fall of Irish Soccer (Dublin, 2006).