‘A long and oddly intertwined history’ – Irish nationalism and Zionism

Aidan Beatty explores the historical links between Irish and Jewish nationalism

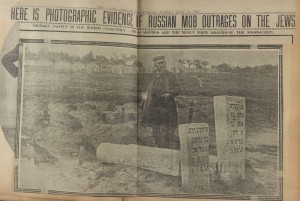

In Easter 1903, the city of Kishinev, in what is now Moldova, was gripped by a four-day anti-Jewish riot. In the grand scheme of Jewish history, the Kishinev Pogrom was hardly the most violent of events; only forty-seven Jews were killed.

In modern Jewish political history, however, the Kishinev Pogrom was of great importance, as its violence led to a huge upsurge in support for Zionism, a movement that had argued since its founding in the 1880s that Jews could have no future in the Diaspora.

The Pogrom would also become a major international event, confirming, for many Westerners, a stereotypical vision of Russian barbarism as well as the view that Russians Jews were in a perilous situation and faced an uncertain future.

The Kishinev pogrom of 1903 converted many Jews to Zionism and also convinced Irish radical and journalist Michael Davitt of the justice of the cause of Jewish nationalism

It was in this context of widespread international attention that William Randolph Hearst’s New York American newspaper announced, in May 1903, that ‘Michael Davitt will go to Russia as the “American’s” special commissioner to investigate the massacres of the Jews.’

The paper went on to claim that ‘no man is better fitted than this liberty loving Irishman to give to the world a true story of the butchery that has been done and the ruin that has been wrought by the fanatics.’[1] In his subsequent book on the Kishinev Pogrom, Within the Pale: the true story of anti-Semitic persecutions in Russia (1903), Davitt declared ‘I have come from a journey through the Jewish Pale, a convinced believer in the remedy of Zionism.’[2]

In his journalistic investigations, Davitt also claimed to have seen something very familiar among the Jewish population of the southern regions of the Russian Empire. He compared the Tsarist police to the RIC and talked of how the Russian Jews are ‘hemmed in and hedged about by penal laws,’[3] a most unambiguous term indeed for an Irish nationalist to use!

Davitt was clearly projecting his own Irish nationalist beliefs onto the plight of Russian Jewry, and saw both the Irish and Jewish nations as facing a shared oppression and a shared lack of political sovereignty.

From Balfour to Black and Tans

Indeed, Zionism and Irish Nationalism have had a long and oddly intertwined history. When the British government announced their support for Zionism in early November 1917, it was in the form of a letter from Foreign Secretary Arthur Balfour to Lord Rothschild, a leading member of the British Jewish community;

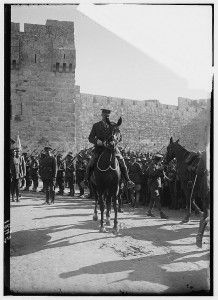

Balfour, of course, had cut his political teeth as Chief Secretary for Ireland and was a staunch opponent of any Irish political autonomy. Shortly after issuing the Balfour Declaration, the British government invaded Palestine and, by December 25, had captured Jerusalem, securing what David Lloyd George was to call ‘a Christmas present to the British people.’

This lustre would soon wear off, though, as Palestinian opposition to British rule and Zionism escalated, starting with the Nebi Musa riots of Easter 1920. Finding themselves in control of an increasingly volatile country, the British called in Hugh Tudor.

A veteran of the Second Boer War, Tudor had recently finished his posting in Ireland as head of the Black and Tans and many ex-Tans were to join him in Palestine, as he established Britain’s police force there. These men probably felt a bizarre sense of déjà vu during the Arab Revolt of 1936-39 when a popular guerrilla campaign caused the British to lose control of much of the country. Indeed, one of the finest studies of British Palestine aptly calls this the period of ‘Ireland in Palestine,’[4] and this sense of déjà vu would soon intensify, as some old names popped up in the most unlikely of places.

In 1939, as war loomed in Europe, the British government, desperate to pacify this strategically important Imperial holding, issued a White Paper that greatly limited immigration into Palestine. Such a halt to Zionist immigration had long been a central Palestinian demand, but from a Jewish perspective this was abominable; as Hitler’s control of Europe extended across the continent, access to one of the last Jewish refuges was being cut off.

Many of the British police force in Mandate Palestine were veterans of counter insurgency in Ireland.

While the mainstream Zionist leadership felt they had no choice but to side with the British during the war against Nazism, more radical nationalist elements felt Britain should be attacked regardless. Many of these latter forces coalesced around Avraham Stern, and became known as LEHI (Lochamei Herut Yisrael, Israel Freedom Fighters).

When Zionist guerrillas confronted British forces in Palestine in the late 1930s and 40s, it was to Ireland and the IRA that they look for inspiration

The parallels with Ireland during the previous world war were clear, and Stern duly proceeded to translate P.S. O’Hegarty’s The Victory of Sinn Féin into Hebrew.[5] O’Hegarty’s unwitting influence on Zionists is perhaps best hinted at by the fact that Yitzhak Shamir, a future Israeli prime minister but an underground LEHI activist in the 1940s, chose the nom de guerre ‘Michael’, in homage to Michael Collins.[6]

Similarly, Avsahlom Haviv, a member of ETZEL (Irgun Tzvai Leumi, The National Military Organisation), a slightly more moderate group than LEHI, quoted George Bernard Shaw during his trial for violent anti-British actions, and accused the British of ‘drowning the Irish Uprising in rivers of blood… yet Ireland rose free in spite of you.’[7]

That the radical right-wing of Zionism was so attracted to Irish nationalism must have been another odd experience for those veterans of the Irish War of Independence now serving in the Palestine Police.

De Valera and Zionism

It was not only the most radical Zionists, however, who saw a parallel with Ireland. Moderate Zionists also took a strong interest. This was partly because of Ireland’s presidency of the League of Nations, under whose auspices British rule in Palestine was supposedly granted.

It was not only the most radical Zionists, however, who saw a parallel with Ireland. Moderate Zionists also took a strong interest. This was partly because of Ireland’s presidency of the League of Nations, under whose auspices British rule in Palestine was supposedly granted.

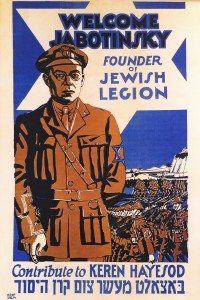

Even if the League of Nations remained something of a paper organisation this did create the amusing situation that Britain was, in theory, answerable to a body headed by a de Valera appointee. It also meant that Ze’ev Jabotinsky, a right-wing Zionist, though one who was never as radical as his followers, was in Dublin in early 1938, seeking diplomatic support for his movement.

He was introduced to de Valera by Robert Briscoe, himself of Jewish background as well as a supporter of right-wing Zionism. Jabotinsky visited the Dáil, met leading members of the small Dublin Jewish community and at the end of his visit pronounced that ‘I have always been an admirer’ of de Valera, ‘and I think he has a most striking personality.’ [8] Indeed Robert Briscoe, in his 1958 autobiography, provides a fanciful account of Jabotinsky’s meeting with de Valera. The Taoiseach was apparently skeptical of the justness of the Zionist project, a situation that his visitor had a readymade response:

‘”Mr. de Valera” said Jabotinsky, “I have been reading Irish history. As a result of the great famine of 1847 and 1848, I believe the population fell from eight million to four million. Now supposing it had been reduced to fifty thousand and the country had been resettled by the Welsh, Scots and English, would you then have given up the claim of Ireland for the Irish?”

Irish Taoiseach Eamon de Valera met with Zionist activist Ze’ev Jabotinsky through Jewish Fianna Fail activist Robert Briscoe in 1938

When de Valera replied that the Irish would never relinquish Ireland, Jabotinsky said neither could the Jews give up their claim to Palestine. Briscoe records that ‘I am not sure, but I think the Chief was convinced by these arguments. Certain it is that I was.’[9]

When the 1937 Royal Commission on Palestine recommended partitioning Palestine, Zionists had another reason for taking an interest in the course of Irish history. Judah Leb Magnes, head of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem and a leading figure in bi-nationalism, a utopian strand of Zionism that sought to create a harmonious Jewish-Arab state, went so far as to seek out Eamon de Valera’s thoughts on partition.

Magnes’ original letter does not appear to have survived (it is not included either in de Valera’s papers in UCD nor in Magnes’ papers in the Central Archive for the History of the Jewish People at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem), but de Valera’s extant reply gives an intimate précis of his views on partition, draws an overt comparison between Ireland and Palestine and suggests that Magnes saw things similarly:

I do not know the Palestine problem as you know it, but from a knowledge of what partition means in Ireland now, and what I am convinced it will mean in the future, I have reached the same conclusion as you have, namely: only by negotiation and free agreement between Jew and Arab… can there be a satisfactory solution. I regard partition as perhaps the worst of the many solutions that have been proposed. [10]

Indeed, when de Valera was visited at this time by the leading British Zionist Prof. Selig Brodetsky, Robert Briscoe warned him ‘not to advocate partition of Palestine, explaining how the Chief would react to that word.’[11]

Using an analogy with Ireland, de Valera advised against partitioning Palestine between Arabs and Jews

In any case, Palestine was partitioned just over a decade later, and the following year the then Minister for External Affairs, Sean McBride, announced to the Dáil: ‘Our common suffering from persecution and certain similarities in the histories of the two races create a special bond of sympathy and understanding between the Irish and Jewish peoples.’[12]

Similarities and differences

But,of course, just as there are comparisons to be made between Zionism and Irish Nationalism, there were also many differences.

The sexual puritanism of Irish nationalism, directly influenced by conservative Catholicism, was largely absent in Zionism. Moreover, Zionism in its formative years was far more comfortable with socialist ideology, and the early history of the movement is peppered with such names as Poalei Tzion [Workers of Zion] and Achdut HaAvoda [Unity of Labour], as well as the Kibbutz movement.

This stands in stark contrast to contemporary Irish nationalists, who often liked to claim they were above such narrow ideologies (even if to make such a claim is, of course, inherently ideological!).

Zionism lacked the sexual puritanism common in early 20th century Irish nationalism and was more influenced by socialist ideas. It was also much more successful in reviving Hebrew than Irish nationalists were in reviving Irish

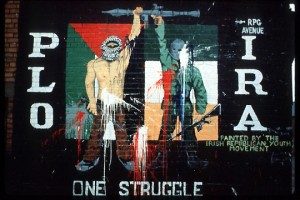

It is ironic, then, that since the late 1960s, as Zionism has drifted ever rightward, Irish Republicanism has been going in the opposite direction, taking on more explicitly socialist and anti-Imperialist tones, and discovering a newfound support for Palestinian nationalism along the way.

In 2002, for instance, during the height of the Second Intifada, An Phoblacht, declared that: ‘Sinn Féin President Gerry Adams has expressed support for the beleaguered Palestinians and their leader… Ariel Sharon’s time in power has been marked by repressive actions akin to the worst years of British oppression in Ireland.’[13] This is a far cry, indeed, from Michael Davitt’s support for Zionism a hundred years earlier, or the one-time declaration that ‘Israel represents the triumph of Sinn Féin.’[14]

Perhaps the most obvious difference, though, is how successful the revival of Hebrew has been, in contrast with the stark failure of the Irish language revival. By the 1940s, not only was there a relatively rich Hebrew print-culture in Palestine, but Hebrew had also become a thriving vernacular language, with a well developed slang, often drawing, surprisingly, on Yiddish or Arabic.

At a certain point, Zionist leaders accepted that a vernacular language cannot be state-controlled, grammatically pure, or free from loan-words or foreign influence (no matter how problematic that foreign influence is from a Zionist perspective) and this was to be a major reason for the success of the Hebrew revival.

Since the 1960s Irish republicans have identified more with the Palestinian cause, accusing Israel of, ‘repressive actions akin to the worst years of British oppression in Ireland’

The failure of Irish nationalists to accept anything like this, either before or after 1922, was to be a key element in their failure to revive the language. They continued to view Irish as a repository of a pure Gaelic culture, free of English influences, and so continued to obsess over notions of linguistic purity.

But linguistic purity, like racial or national purity, is a myth. Irish nationalists failed to recognise that all vernacular languages are constantly in flux, constantly borrowing from other languages, and rarely grammatically pure. Rather than protect and revive the language, the Irish state, thus, ultimately smothered it.

Aidan Beatty is pursuing a PHD at the University of Chicago on a comparison between Irish nationalism and Zionism.

[1] New York American, 13 May 1903, in TCD Michael Davitt Papers MS9670 Press Cuttings, September 1902-May 1903.

[2] Michael Davitt. Within the Pale: The True Story of Anti-Semitic Persecution in Russia (New York: Barnes and Noble, 1903) 86.

[3] Ibid, 233-234, 82. Emphases added.

[4] Tom Segev. One Palestine, Complete: Arabs and Jews Under the British Mandate (New York: Henry Holt, 2001) 415

[5] Colin Shindler. The Land Beyond Promise: Israel, Likud and the Zionist Dream (London: I.B. Tauris, 2002) 31

[6] Colin Shindler. Letter: ‘Sinn Fein [sic] and the Zionists’ The Guardian, 23 May 2003.

http://www.guardian.co.uk/theguardian/2003/may/23/guardianletters

[7] Shindler, ‘Land Beyond Promise’ (2002) 31.

[8] Irish Independent, 8 & 12 January 1938.

[9] Robert Briscoe; Alden Hatch. For the Life of Me (Boston MA: Little, Brown & Co., 1958) 264-265.

[10] CAHJP Judah Leb Magnes Papers P3/2424, Letter to Judah Leb Magnes from Eamon De Valera, 10 September 1937.

[11] Briscoe, ‘For the Life of Me’ (1958) 266.

[12] Shulamit Eliash, The Harp and the Shield of David: Ireland, Zionism, and the State of Israel (London: Routledge, 2007) 102. Quoted in Peter Hession. ‘Advanced Nationalism and Zionism: Contradictions and Explanations’, paper presented at Irish and Jewish Identities: Links and Parallels, Conference, University of Chicago, 22 February 2011.

[13] ‘Defend Palestine’, An Phoblacht, 4 April 2002. http://www.anphoblacht.com/contents/8600

[14] Sinn Féin, 16 Mar. 1912, p. 2. Quoted in Hession ‘Advanced Nationalism’ (2011).