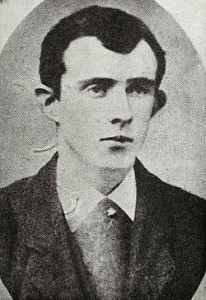

Thomas Clarke Treason Felony Convict J464

Shane Kenna tells the story of the arrest and harrowing imprisonment of Tom Clarke, one of the architects of the 1916 Rising, in 1883 for his role in Fenian bombing campaign in England.

The dynamite war

Between 1881 and 1885 Two Irish-American organisations ‘the United Irishmen of America’ under O’Donovan Rossa and Clan na Gael under Alexander Sullivan led a bombing campaign in Britain. Since 1881 the Clan followed a policy of active work, with teams of Irish-American dynamitards travelling to the United Kingdom to reconnoitre sites for dynamite attacks in British cities, in retaliation for British policy during the Land War in Ireland. While the cities of Liverpool and Glasgow were attacked by dynamitards, London suffered most.

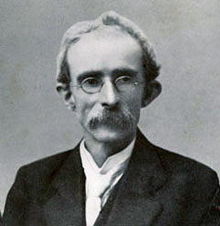

Clan na Gael sent a team including Tom Clarke, led by Dr. Thomas Gallagher to bomb London

The first Clan mission was headed by the Brooklyn resident Doctor Thomas Gallagher and consisted of James J. Murphy, John Kent, William Lynch and Thomas J. Clarke. Joined by Gallagher’s brother Bernard they set about establishing a bomb manufacturing factory in Birmingham, disguised as a paint and decoration shop under the ownership of Murphy. From Murphy’s shop in Birmingham nitro-glycerine explosive was manufactured and transported to London by means of rubber bags and fish stockings enclosed in large portmanteau’s and boxes, and it was planned to attack major symbolic political sites in London sometime in late April 1883.

Arrest

The Gallagher team was arrested in April 1883 following a major police surveillance operation in Birmingham, involving entering the premises at night to survey the materials. Lynch having travelled from Murphy’s explosive factory, had been followed by a Birmingham police sergeant to London and his lodgings raided where he was found to be in possession of nitro-glycerine, a number of photographs, a map of London, and an envelope bearing the name Mr. Thomas Gallagher. Fearing news of Lynch’s arrest, the Birmingham constabulary chose to search Murphy’s shop soon afterwards, where police had discovered over 170lbs of nitro-glycerine:

The team was cuaght in possession of nitroglycerine and maps of London

In a sitting room at the back of the shop… a quantity of nitric and sulphuric acid, and some books and papers connecting the occupant with the United States. In the scullery there was more of the same acids; while in the furnace, there was an earthenware vat containing a white fluid material in course of manufacture. There was a further supply of similar material in other parts of the room and premises.

Following an extensive search, an eager constable discovered a notebook signed by Tom Clarke and a letter giving his address at Nelson Square London. This gave the police a definitive lead and Scotland Yard was immediately informed of the development. With the net beginning to close around Clarke, the police moved into mobilisation under inspector John Littlechild. Littlechild waited for Clarke’s arrival at his apartment prior to raiding the accommodation, and at half past one Clarke arrived with Gallagher and as he turned the key to open his apartment door, Police swooped on the two men. On investigation Littlechild found Clarke had a large portmanteau in his room containing:

two India rubber cases, each about 2ft long… apparently full of something

Littlechild had found nitro-glycerine and Clarke was arrested. Gallagher could have reasonably argued that he knew nothing of the plot, but given the surveillance operation carried out he could not escape arrest and evidence began to mount against him. His brother Bernard and Curtin were later arrested and the Gallagher team were broken.

Trial and detention

On Monday 11 June 1883 Thomas Clarke stood trial with his colleagues, accused of attempting to levy war upon the Queen ‘in order to compel her to change her measures and counsel, and in order to intimidate and overawe both Houses of Parliament.’ Lynch had turned and offered his assistance to the prosecution to secure a conviction of the team, and his evidence indicated a number of targets the dynamitards had intended to attack including the Palace of Westminster. There is significant evidence however to suggest that Lynch was lying, as were the prosecution who denied the stringent surveillance of the team in Birmingham. According to them :

no one knew anything of the coming or going of these men: nobody who had to protect the law of this country knew of the arrival of these men from America or aught else.

These misrepresentations of fact, which were intended to engage the fears of the public and the jury, succeeding in securing a conviction as on Thursday 14 June when the jury found Gallagher, Clarke, Murphy and John Kent guilty, sentencing to life imprisonment. Bernard Gallagher was acquitted while Lynch, for his services, was rewarded with exoneration. Clarke recalled:

we were hustled out of the dock into the prison van, surrounded by a troop of mounted police, and driven away at a furious pace through the howling mobs that thronged the streets from the Courthouse to Millbank prison. London was panic stricken at the time.

At Millbank Clarke and his fellow dynamitards were placed in temporary detention and were then convoyed to Chatham and Portland prisons respectively. Clarke now facing the darkest period of his life recalled:

Had anyone told me before the prison doors closed upon me that it was possible for any human being to endure what Irish prisoners have endured in Chatham Prison, and come out of it alive and sane, I would not have believed him.

In prison the Fenians were maked out as ‘special men’ , kept in contact solitary confinment and forbidden to speak

Immediately Clarke learned silence was rigidly enforced and the convict should reflect on what he had done. Under no circumstances was he to make contact with fellow dynamitards, and if he did punishment would be severely enforced. Clarke recalled how, to escape this monotony, dynamitard convicts determined to keep in contact with each other. Using lead in the pivots of their cell doors, they made makeshift pencils and wrote messages on regulation brown paper. In the dreary, dark and dull atmosphere of prison, this kind of communication with his fellow Irish prisoners was something he could look forward to and enjoy, despite the punishment it would bring if discovered.

Clarke recalls the harrowing story of dynamitards being treated with contempt and anger within the walls of Chatham and Portland, finding they were treated as ‘special men.’ This title, reserved specifically for the dynamitard convict was terrifying given that it entailed strict rules and stricter punishments. These ‘special men’ found gaolers and wardens treated them as they pleased, often relinquishing ordinary rules for prison regulation, and implementing an unvarying system of persistent harassment:

we treason felony prisoners were known as… the ‘special men,’… kept, not in ordinary prison halls but in penal cells- kept there so that we could be more conveniently persecuted, for the authorities aimed at making life unbearable for us. The ordinary rules regulating the treatment of prisoners, which, to some extent, shield them form foul play and the caprice of petty officers, these rules as far as they did that, were in our case set aside… This was a scientific system of perpetual and persistent harassing… harassing morning, noon and night, and on through the night, harassing always and at all times, harassing with bread and water punishments, and other punishments with ‘no sleep’ torture and other tortures. This system was applied to the Irish prisoners and, to them only, and was specially designed to destroy us mentally or physically – to kill or drive insane.

Insanity

As a result of the treatment dynamitards received in prison, many broke under the strain, drifting into psychosis and lunacy. Clarke recalled his fear of looming insanity when he noticed a constant ringing, which he feared to be in his head. Much to his delight he discovered this ringing was coming from a fresh telegraph wire outside which he had not seen. Clarke expressed joy that he was not losing his mind on that occasion, but the thought continued to haunt him for some time particularly as he noticed:

one by one, I saw my fellow prisoners break down and go mad under terrible strain – some slowly and by degrees, others suddenly and without warning. “Who next” was the terrible question that haunted us day and night – and the ever recurring thought that it might be myself, added to the agony.

As a result of the treatment dynamitards received in prison, many broke under the strain, drifting into psychosis and lunacy

Dr. Gallagher had collapsed under the mental strain and refused to work claiming to be God. He could not hold his food and began vomiting intensely reducing himself to an extremely low state. Clarke spent sleepless nights in his cell listening to Murphy ‘fight against insanity, cursing England and English brutality form the bottom of his heart, and beseeching God to strike him dead sooner than allow him to lose his reason.’ Clarke discussed his fears with the Catholic Chaplin who while listening attentively, dismissed the matter, fearing the Prison authorities would cause trouble with his Bishop. Clarke, while disheartened, was not to be beaten and wrote to John Redmond MP detailing the treatment of his friends. He learned his letter had been suppressed by the Prison authorities. Redmond however later came to visit the dynamitards and Clarke discussed his fears, finding the MP would approach the Home Secretary to examine the men’s condition.

The Home Office agreed to the demand and doctors were sent into the hospital to examine Gallagher and Whitehead. However, they found the two were feigning insanity and looking for special treatment. This resulted in further punishment for the two dynamitards, worsening their mental situations and as these situations worsened, it was continuously noted that their declining health was a result of their efforts to feign insanity.

The convicts successfully publicised their sufferings, by means of letters and visits from Irish politicians. The resulting public outcry was deafening and despite a growing publicity campaign in the United States and Ireland regarding their degrading treatment, continued pleas and petitions for their release were ignored.

In Ireland an Amnesty Association was formed to lobby the government demanding immediate action and succeeded in persuading the Home Office to allow an American doctor, St. John Gaffney, to examine Gallagher and Murphy. Gaffney found them clinically insane. The government disagreed and a further British doctor examined the men overruling Gaffney pronouncing them reasonable. For a further three years they stayed in this condition, continuously degrading.

Release

Tom Clarke was released from prison in 1898 after 15 years in prison. His health never fully recovered.

By 1896 Dr. Gallagher was released from Portland and emerged a physical and mental wreck. The government had finally concluded that further incarceration would result in his death. Arriving in America it was noted he was:

a raving maniac… not one of his friends would have known him. The handsome, stalwart Irishman of thirteen years ago had become almost an old man. His form still strong, is bent and emaciated. His sunken cheeks are covered with a closely clipped grey beard, and his hair has become but a narrow rim of white about his bald head. His deep set eyes gleam with the restless light of an unbalanced mind.

Murphy returned to Cork, where he promptly disappeared from his family. He was finally discovered dishevelled searching for a boat to America. Both were incarcerated in insane asylums. Thomas Clarke remained imprisoned and was the last of the dynamitards to be released. He recalled that his prison life had never been so lonely and now lived in strict silence alone with his thoughts he found his imprisonment to be like ‘a sailor’s rope that had no end to it.’ As Clarke lay his cell, the one inspiration in his prison life was his love for Ireland:

The struggle for Irish freedom has gone on for centuries, and in the course of it a well trodden path has been made that leads to the scaffold and to the prison. Many of our revered dead have trod that path, and it was these memories that inspired me with sufficient courage to walk part of the way along that path with an upright head.

In September 1898, Thomas J. Clarke was released on license from Portland Prison. The medical officer concluded that his health had deteriorated resulting from long imprisonment. He had chronic arthritis in the left knee and had developed a heart murmur, despite the fact he was only thirty-seven years of age. He soon after moved to America marrying the niece of fellow dynamite internee John Daly’s, Cathleen and becoming secretary to John Devoy in Clan na Gael.

In 1907 he finally returned to Ireland where he opened a tobacco shop in Parnell Street and became actively involved in rebuilding the Irish Republican Brotherhood with Seán MacDiarmada and Bulmer Hobson. He later sat on the IRB military council planning the Easter Rising of 1916 and took part in the insurrection in the General Post Office, afforded the honour of being the first signature to Easter proclamation.

In 1916 Clarke’s was teh first signature on the proclamation of the insurgents’ Irish Republic

Clarke was to be President of the insurgents’ Republic, but refused military honours and stood aside for Patrick Pearse to assume to the role. On 3 May 1916 he was executed by firing squad in Kilmainham Gaol Dublin. Prior to his execution his wife Cathleen was allowed visit him in his cell in the prison. He told her he was relieved to be executed, as he dreaded a return to prison. Giving her a note to the Irish people his epitaph read:

I and my fellow prisoners believe we have struck the first successful blow for Irish freedom. The next blow, which we have no doubt Ireland will strike, will win through. In this we die happy.

Further reading

Clarke, Thomas, Glimpses of an Irish felons prison life (Dublin, 1922)