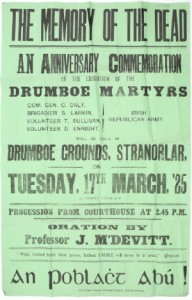

Today in Irish History, The execution of the “Drumboe Martyrs”, 14 March 1923

Kieran Glennon tells the story of the four Republicans executed in Donegal in 1923, by among others, his grandfather.

Four Republicans, who subsequently became known as the “Drumboe Martyrs”, were executed by a Free State firing squad in Donegal in March 1923. None of the four was from that county – all had come there as part of a joint campaign against the north involving both the Provisional Government and their anti-Treaty opponents.

Encapsulating the tragedies of the Civil War, not only were there personal ties between their leader, Charlie Daly, and his Free State opponent, Joe Sweeney, but the former may have previously saved the latter’s life. To add further poignancy, it is quite likely the men were executed in reprisal for a shooting that was not part of the civil war at all.

I should, at the very outset, clarify that the Tom Glennon referred to in this article, as a Free State officer, was my grandfather. While it is natural and understandable that some readers may fear that this will lead to family bias on my part, I hope the article will prove any such concerns to have been unnecessary.

Background

The Civil War in Donegal had an almost-uniquely northern dimension.

Firstly, two of the key protagonists’ involvement in the War of Independence had been in the north. Originally from Kerry, Charlie Daly had been appointed as a full-time IRA organiser in October 1920, responsible for Tyrone and the rural part of Co. Derry. He went on to command the 2nd Northern Division in this area until early March 1922, when he was removed due to his opposition to the Treaty. By mid-1922, he was Vice-Commandant of the Republican forces in Donegal.

On the other side, the Free State officer Tom Glennon was originally from Belfast. The month after Daly’s appointment as a full-time organiser in Derry-Tyrone, he had been appointed to an identical role in Co. Antrim, later becoming Officer Commanding of the Antrim Brigade until he was captured; his area of responsibility thus directly bordered Daly’s to the east. In November 1921, following his escape from internment in the Curragh, he was appointed Adjutant to the IRA’s 1st Northern Division in Donegal.

Secondly, and more significantly, the overwhelming majority of Republican forces in Donegal were from outside the county and were there directly because of the situation in the north. In April 1922, as part of their efforts to maintain unity in the IRA in the face of the split over the Treaty, Michael Collins and Liam Lynch had agreed on a joint military strategy to attack the Northern Ireland government.

None of those executed at Drumboe were from Donegal. They had come there to fight the Northern government.

The Provisional Government swapped British-supplied rifles with anti-Treaty units in Munster, the southern weapons then being smuggled into the north for use by local units of the IRA in staging an uprising in May.

For their part, the Republican Army Executive in the Four Courts agreed to send men from anti-Treaty units of the IRA in Cork and Kerry up to Donegal, under the leadership of Cork man Seán Lehane, in order to launch attacks across the border. By early July, Free State Chief of Staff Eoin O’Duffy estimated that 700 Munster Republicans were in Donegal 1; in addition, several hundred anti-Treaty members of Daly’s old division had fled west from Tyrone and Derry to avoid internment.

However, what had been planned as a united campaign against the north instead saw the first fatal clashes between pro- and anti-Treaty forces in the country. For reasons that have never been clearly established, the Free State commander in Donegal, Comdt.-General Joe Sweeney, refused to co-operate with Lehane’s forces. This led to increasing tensions in the county, culminating in a gun-battle between the two sides in Newtowncunningham on 4th May in which four Free State soldiers were killed. 2

Early stages of the Civil War in Donegal

The day after Free State troops began shelling the Four Courts in Dublin on 28th June 1922, Sweeney’s troops launched a swift offensive in Donegal, rapidly over-running and capturing Republican posts at Finner Camp, Buncrana, Ballyshannon, Bundoran and Carndonagh, taking several hundred prisoners in the process. 3

In the early stages of the civil war in Donegal, Free State forces rapidly overran the Republican positions

Co-ordination of Republican resistance was weakened by the fact that at the outset of the fighting, Lehane was in Dublin, taking part in unity negotiations following a split in Republican ranks at an Army Convention on 18th June; he did not return to Donegal until mid-July, having had to walk all the way from Sligo. In his absence, Daly withdrew much of the remaining Republican force to Glenveagh Castle in west Donegal, where he established a new headquarters.

One IRA man wanted to ‘plug’ Free State officers Sweeney and Glennon when they arrived for negotiations. It was Charlie Daly who stopped him.

There were immediate attempts to negotiate an end to the fighting. On the morning of 5th July, Sweeney and Glennon travelled under a promise of safe passage to meet Daly and some of his senior officers at Churchill, near his headquarters. Sweeney hoped to agree a basis on which the southern Republicans would leave Donegal; in the event, neither side was prepared to accept the conditions proposed by the other and the negotiations proved fruitless. However, it was the immediate aftermath of the meeting which was to prove poignant several months later.

According to Republican Mick O’Donoghue, Daly saved the lives of the two Free State officers:

“As Sweeney, Daly, Glennon, Cotter and I dallied at the door, Jim Lane… slouched in and beckoned me over. I went. ‘Jordan and some of the northern fellows outside are threatening to ambush Sweeney and plug him on the way back,’ Lane whispered to me. I was startled.

Knowing Jordan’s reputation for recklessness and bloodthirsty callousness, I would not put such a thing beyond him. We had given Sweeney a pledge of safe conduct and he had trusted in our word of honour … Approaching the group at the door, I called Charlie aside and asked the others to hold us excused for a few moments.

Briefly I told Daly what was afoot outside. He was appalled. The soul of honour himself, he could hardly believe that any Republican soldier could stoop to such treachery and disgrace and dishonour a pledge of safe conduct … Calling Lane, he ordered him to see that none of the Republicans moved out of Churchill until Sweeney had gone, and to stay side by side with Jordan to prevent him from any rash attempt to carry out his threat.” 4

Unaware that Daly had just prevented their deaths, Sweeney and Glennon left to return to their headquarters at Drumboe Castle.

The Free State offensive resumed the following day and they captured more Republican bases at Skeog and Inch Island in mid-July. By then, the Republican force at Glenveagh had been whittled down to eighty and Lehane decided to take his remaining men on the run. As the Republican column separated into ever-smaller groups to avoid detection and capture, the next three months saw a protracted game of cat-and-mouse with pursuing Free State forces.

Daly had already been ordered to evacuate his men from Donegal when he was captured

At the beginning of November, Republican GHQ bowed to the inevitable and ordered the evacuation of Donegal by their forces. Lehane sent the following despatch to Daly, whose tiny group was still hiding out in the northwest of the county:

“I have received an order from E. O Maille [Ernie O’Malley] authorising us to leave Donegal at once and withdraw our men. I believe our work here is impossible. We have to steal about here like criminals at night, and it gets on one’s nerves. In order that we may try and make arrangements, could you please bring your lads on towards Drumkeen and we will go that length to meet you … We will be able to talk things over there … Until I see you and the lads, good luck. Seán Ó Liatháin.” 5

Daly did not make it to the rendezvous – on 4th November, the usual sequence of weekly intelligence reports from Drumboe Castle to Free State GHQ at Beggars Bush was broken for a special message:

“A flying column of Irregulars were captured at Meenabaul, Dunlewy on Tuesday night, 2nd inst., by troops operating from Glenveagh Castle under Lieutenant-Commandant McBrearty. Charles Daly, late O/C 2nd Northern Division was in charge. He was acting as Deputy O/C 1st & 2nd Northern Divisions (Irregular).” 6

The capture and trial of Charlie Daly

Daly later admitted that the night they were captured, he and his men were too exhausted to even post a sentry:

“After their capture, Charlie wrote me and told me the reason that they did not put out a guard was that not a man was fit to stand on guard duty. They had travelled several miles over the mountains and were dead on their feet and so took a chance.” 7

A vivid description of the arrest was given some time later by one of his former officers, Séamus McCann from Derry:

“Donegal was very much for the Treaty with the result it was very hard to operate, the column having to walk long distances to get to friendly houses. Charlie and his little party were getting it tough, with a large, well-equipped army on his tail. They could only spend one night in any townland. They had just arrived in the townland of Dunlewy and were dead beat. They had just lay down with their boots on when the house was surrounded by a large force of military. Charlie reached for his rifle half asleep. But before he could do so he received a blow from a rifle butt. Charlie and his little band were taken prisoner and lodged at Drumboe Castle.” 8

According to Free State officer Denis Houston, a large force of Free State soldiers acting on a tip-off had arrived at Meenabaul near Gweedore at 7:15pm on the evening of 2nd November and had gone to search the house of John Sharkey:

“I saw Francis Ward and Daniel Coyle both of whom I recognised in the kitchen and three other men who were strangers to me. They were put under arrest and then the soldiers proceeded to another room off the kitchen. A man opened the door of the room whom I recognised as Charlie Daly. He was put under arrest and immediately stated he accepted responsibility for all of the men arrested and that he was in charge.” 9

Two other Republicans were arrested in another house nearby.

Although the required documents were initially prepared at the end of November, the court martial did not finally convene until 18th January 1923, some two and a half months after the men’s arrest. The prosecutor was a Mr. Cunningham and the court was made up of Deputy Divisional Commandant Joe Seán McLoughlin and State Solicitor William McMenamin. The third member of the court was Tom Glennon: he was now going to hear the case against the man who – probably unknown to him – had saved his life after the abortive peace meeting in Churchill the previous July.

The six men arrested by Houston were each charged with being in possession of three rifles, a revolver, 300 rounds of .303 ammunition, six rounds of .45 ammunition and a German egg bomb “without proper authority”. The other two Republicans were charged with being in possession of three rifles, three revolvers, three bandoliers of .303 ammunition and a pouch of .45 ammunition “without proper authority.”

The eight republicans were found guilty of bearing arms, ‘without the proper authority’ but heard nothing of their sentence for over three months.

The only likely outcome was that all eight would be found guilty which, given the charges, the evidence and the provisions of the Public Safety Act passed the previous October, meant possible death by firing squad. Daly might have sought a lighter sentence by appealing to his past friendship with Sweeney (they had been in university together) or by pointing to his saving of Sweeney’s and Glennon’s lives at Churchill and subsequently going out of his way to get medical aid for two Free State soldiers wounded in an action at Drumkeen in mid-July. But he did not. These actions would suggest that Daly’s nature as an officer was too honourable to even contemplate such a course.

The Republicans were found guilty by the court martial, but no sentence was passed at first. Three weeks after the trial, one of the men, Tim O’Sullivan from Kerry, wrote in a letter to a long-term girlfriend: “Nothing strange here only that we were court-martialled on Jan. 18th and we got no account of it since. We are as happy as the flowers in May.” 10

Rumours that death sentences would be handed down did spread as both Donegal County Council and Dunfanaghy Rural District Council discussed the issue at their respective meetings during February – the latter passed a motion calling on the government “to exercise their prerogative of mercy and not to inflict the extreme penalty in these cases.” 11

The eight men – Daly and O’Sullivan from Kerry, Dan Enright also from Kerry, Seán Larkin and James Donaghy from Derry, Dan Coyle and Frank Ward from Donegal and Jim Lane from Cork – remained in a cell together in Drumboe Castle, still unaware of their fate but prepared for the worst. Daly was visited regularly by C.S. Sweeney, one of the Free State soldiers wounded at Drumkeen: “Eleanor [C.S. Sweeney’s wife] was indignant but C.S. took the view that Daly could have dropped both him and Harkin in a bog hole.” 12

C.S. Sweeney may not have been the only Free State soldier sympathetic to the plight of Daly and the others. In his autobiography, written ten years later, Peadar O’Donnell, the prominent Donegal Republican, referred to a soldier named Dan McGee as “…the one man in Tirconaill who was a volunteer in enemy uniform. This youngster had just failed to effect the release of Daly, Larkin, Enright and O’Sullivan.” 13

The “Drumboe Martyrs”

Although they had been found guilty of possession of weapons and ammunition, the “Drumboe Martyrs” were shot in reprisal for the killing of a Free State officer.

At 1:40pm on 11th March, a brief radio message was despatched from Drumboe Castle to GHQ in Dublin: “Captain Bernard Cannon killed in attack in Creeslough Post last night. Particulars later.” 14 At first sight, this might seem to be the outcome of an attack by Republicans, but the reality is murkier. Ernie O’Malley noted that Republicans believed there had been a fight among the Free State soldiers in the barracks:

“Both Peadar O’Donnell and Joe Sweeney discussed the shooting of Cannon in my presence. Frank O’Donnell, Peadar said, told Cannon’s father the man who had shot him and he was Free State. Joe Sweeney said he investigated the shooting but found that Lt. Cannon had been shot through the skylight of the front door.” 15

In a separate interview, O’Malley talked to Sweeney alone, who told him:

“One of our officers, Lt. Cannon, was killed in the barracks at Creeslough. The barracks had been fired at. He went into the hall and was shot dead … I was talking to Peadar and Frank O’Donnell about the shooting of Lt. Cannon. They are positive none of their men were there that night. Nor was there a row in the barracks that night which I thought there might have been for I examined the scene. Outside, behind a wall, we found a box of cartridges.” 16

At the inquest into the dead soldier’s death, a Sergeant Gallagher told how he had been out on patrol, after which the soldiers returned to the barracks. At around 11pm that night, shots were fired at the barracks and he went into the hall, where he saw Cannon had been hit; he dragged him into another room and said an Act of Contrition which the officer repeated, but Cannon died ten minutes later. Gallagher said the shooting at the barracks continued for another hour. 17

But Cannon may have fallen victim not to the Civil War but to the violent lawlessness that accompanied it. In the absence of the disbanded RIC and with the Garda Siochána only recently-established, responsibility for maintaining law and order fell to whichever military group controlled a particular area. As everyday policing could not be their main priority, parts of Donegal – in particular, the east of the county, with its sizeable but vulnerable unionist community – descended into semi-anarchic chaos during the Civil War, with frequent reports of armed robbers preying on the population. According to local historian, Fr. John Silke, the attack on the barracks was mounted by locals after the Army’s arrest of some men in the village:

“On Saturday, March 10, the date of the village monthly fair, the barrack was providing hospitality for the night to a number of men who had imbibed well, if not too wisely and whom the Army patrol had rounded up. Shots were fired at the barrack from across a stone wall on the other side of the then Ferry’s Bar and Baird’s forge … the inexperienced captain unwisely opened the door and was shot.” 18

It is thus very possible that the denials of responsibility by both Sweeney and the O’Donnell brothers were well-founded and that the dead officer was actually killed by friends of the arrested drunks who were neither Republicans nor Free State soldiers.

Daly and his men were shot for the killing of a Lt. Cannon – who was probably killed by armed local criminals

By that time, the conduct of the Civil War was increasingly bitter. The attack on Creeslough barracks came less than a week after the infamous series of atrocities in Kerry, (in which 24 prisoners were killed in a two week period) but whether there was any connection between those events and the fact that three of the prisoners in Drumboe Castle were from Kerry can only be speculated on. However, when Sweeney reported the fatality at Creeslough to GHQ, the reply was unequivocal:

“We reported it and back came an order to execute four men, one of them Larkin. I sent a wireless message back for confirmation. The same message came back later. Then I sent a message direct to the A/G [Adjutant-General] Gearóid O’Sullivan. Larkin’s name came back again. He was from the Six Counties and I didn’t want to shoot a man from the Six Counties. I was very fond of Charlie Daly. He had been tried shortly after he was arrested but the sentence was confirmed.” 19

Even while Sweeney was arguing with GHQ, the eight prisoners in Drumboe Castle still had no idea what had happened – as late as 12th March, two days after Cannon’s death in Creeslough, O’Sullivan wrote to a fellow Republican who had been arrested in Listowel: “We were court-martialled here on the 18th January. The charge was unlawful possession of arms and we have heard no account about it since.” 20

The following afternoon, four of the men – Daly, O’Sullivan, Enright and Larkin – were informed that they would be executed the next morning. That evening, in a final letter to his mother, Enright wrote: “The sentence of death is just after being passed upon me, but I am taking it like a soldier should.” 21 Although all eight had been found guilty, O’Sullivan wrote in a farewell letter to his friend Maurice O’Connor that “My other four comrades are spared for the present, Dan, Charles, Sean Larkin and I being pulled out.” 22

A few hours before dawn, Daly wrote a last letter to his own mother: “We got the news about four this evening. Though ‘twas rather sudden it was not altogether unexpected; besides we had never lost sight of the possibility of our C.M. ending at death.” 23

‘It is an awful thing to kill a man you know in cold blood’: Joe Sweeney

Daly’s cousin was Dr. Charles O’Sullivan, Bishop of Kerry and although he disapproved of Daly’s actions, it was perhaps through his contacts that Archbishop Patrick O’Donnell of Raphoe diocese called on a meeting of diocesan clergy to plead for the lives of the condemned men. A phone call was made to Minister for Defence Richard Mulcahy but the plea for clemency fell on deaf ears. 24

While Mulcahy was unyielding, Sweeney was torn over the death sentences:

“The terrible thing then was that Daly had to be executed. We had received word from Dublin that anyone captured carrying arms was to be court-martialled and sentenced to death. I had to do the job myself, to order a firing party for the execution, and it was particularly difficult because Daly and I had been very friendly when we were students, and it is an awful thing to kill a man you know in cold blood, if you’re on level terms with him. Trading shots with a man in battle is one thing, but an execution is something else altogether. I wasn’t present at the execution myself but to make sure there was no foul-up the firing party were all picked men and they were told that they were to put them out of pain as quickly as possible. At that time you had this barbarous system where the Provost-Marshall had to go along afterwards to deliver the coup de grace through the heart. I didn’t agree with it but they were orders and you had to do it.” 25

C.S. Sweeney visited Daly again on the evening of 13th March – “Daly told [him] that while Larkin had a death wish, he himself did not want to die.” 26 But after a visit from a priest who heard his confession, Daly reconciled himself to his fate and found great solace in his religious beliefs; his final letter to his mother is couched almost entirely in spiritual terms: “I am now within a few short hours of death and writing you with perfect calmness, all I think of is Eternity and I am ready to go out at 7 o’clock and face the firing squad with confidence and hope in God’s great mercy for the salvation of my soul.” 27

At 8am the next morning, Daly, O’Sullivan, Enright and Larkin were taken into the woods outside Drumboe Castleand shot: “[Comdt.-General Joe Sweeney] went off before the executions, which were left, according to C.S. Sweeney, to a firing party made up of ex-British Army veterans, with Comdt. Sheerin as detail officer.” 28 Later that day, a terse statement from GHQ simply stated that “All four accused were found guilty and sentenced to death. The findings and sentences were duly confirmed in each case.” 29

A week after the executions, Fr. McMullan, the Free State army chaplain at Drumboe Castle, wrote to Fr. Brennan, parish priest of Daly’s home village of Castlemaine in Kerry, paying tribute to how Daly had faced his death:

“I felt, too, that he was a tower of strength to the others all of whom like him met their deaths like true heroes. It was touching to see his generosity of nature, no word of complaint or recrimination, every man acted for the best and according to his lights so that those who differed from them were just as right and well intentioned as himself, such was his creed. He was emphatic in his appreciation of the kindness and consideration shown by all, those offices and men in whose custody he was, and this he expressed to me not only that night, but more than once before.” 30

‘I was a soldier, not a politician’: Tom Glennon

It seems likely that the attack on Creeslough barracks which led to the death of Captain Cannon was – without being properly investigated – simply presumed to have been carried out by the most obvious suspects. As a result of this mistaken attribution, the men subsequently known as the “Drumboe Martyrs” were then executed in reprisal for a killing which had not even been committed by Republicans.

In the aftermath of the Civil War, Joe Sweeney tried to block out all memory of the events:

“It’s very hard to describe a war among brothers. It was fierce and it was atrocious. You had family against family and brother against brother, and I’ve tried to wipe it out of my mind as much as possible because it is not pleasant to think about.” 31

Similarly, Tom Glennon kept his memories to himself and never spoke in later life about his experiences in either the War of Independence or the Civil War. Once – and only once – his son tried to broach the subject of the Civil War, asking his father what he had thought of the Republicans’ position on the Treaty. His father brought the conversation to an abrupt end, declaring “I was a soldier, not a politician.”

Notes

- Report on 1st Northern Division, 3rd July 1922, Mulcahy papers, UCD Archives, P7/B/106. Historian Robert Lynch estimates that the Munster Republicans in Donegal numbered “at most one hundred” (Donegal and the Joint-IRA Northern Offensive, May-November 1922, Irish Historical Studies, Volume XXXV, No. 138, November 2006) but in view of the number of prisoners subsequently captured by Free State troops, this estimate seems too low.

- Derry Journal, 5th & 8th May 1922

- Ibid, 3rd July 1922

- Michael O’Donoghue statement, Bureau of Military History, Military Archives, WS 1741

- Seán Lehane despatch to Charlie Daly, undated, O’Malley papers, UCD Archives, P17a/76

- Donegal Command Intelligence Report,4th November 1922, Military Archives, CW/OPS/06/11

- Martin Quille letter to Paddy —, undated, in James Quinn, The Story of the Drumboe Martyrs, (McKinney & Callaghan, 1958), p49

- Seamus McCann letter to Fr. David, Capuchin Franciscan monastery, Letterkenny, undated, O’Donoghue papers, NLI, Ms 31,315

- Abstract of evidence for court martial, O’Malley papers, UCD Archives, P17a/191

- Timothy O’Sullivan letter to Helena Maye, 9th February 1923, O’Mahony papers, NLI, Ms 44,055/1

- Derry Journal, 21st February 1923

- Fr. John Silke, The Drumboe Martyrs, Donegal Annual, Volume 60 (2008)

- Peadar O’Donnell, The Gates Flew Open (Mercier, 1932), p159

- Donegal Command radio report, Military Archives, CW/OPS/06/12

- Joe Sweeney & Peadar O’Donnell interview, O’Malley notebooks, UCD Archives, P17/b/98

- Joe Sweeney interview, O’Malley notebooks, UCD Archives, P17b/97

- Derry Journal, 16th March 1923

- Silke, The Drumboe Martyrs

- Joe Sweeney interview, O’Malley notebooks, UCD Archives, P17b/97

- Timothy O’Sullivan letter to Michael McElligott, 12th March 1923, in Quinn, The Story of the Drumboe Martyrs, p45

- Dan Enright letter to his mother, 13th March 1923, in Quinn, The Story of the Drumboe Martyrs, p50

- Timothy O’Sullivan letter to Maurice O’Connor, 13th March 1923, in Quinn, The Story of the Drumboe Martyrs, p43

- Charlie Daly letter to his mother, 14th March 1923, O’Donoghue papers, NLI Ms 31,315

- Silke, The Drumboe Martyrs

- Joe Sweeney, interviewed in Kenneth Griffiths & Timothy O’Grady, Curious Journey (Hutchinson, 1982), p305-306

- Silke, The Drumboe Martyrs

- Charlie Daly letter to his mother, 14th March 1923, O’Donoghue papers, NLI, Ms 31,315

- Silke, The Drumboe Martyrs

- Derry Journal, 16th March 1923

- Fr. McMullan letter to Fr. Brennan, 21st March 1923, in Quinn, The Story of the Drumboe Martyrs, p27

- Sweeney, interviewed in Griffiths & O’Grady, Curious Journey, p306