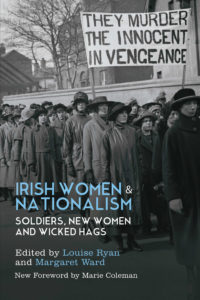

Book Review: Irish women and nationalism: soldiers, new women and wicked hags

By Louise Ryan and Margaret Ward (eds)

By Louise Ryan and Margaret Ward (eds)

Published by Irish Academic Press. (Newbridge, 2019)

Reviewer: Aaron Ó Maonaigh

Originally published in 2004, this collection of essays examines women’s contribution to the Irish nationalist movement over the course of the past four centuries. This timely republication no doubt gives a clear indication of the healthy status of the ever-increasing (if not long overdue) interest in areas of women’s history.

This collection of essays examines women’s contribution to the Irish nationalist movement over the course of the past four centuries

In the traditional narrative of Irish nationalism little recognition has been given to the part played by women. Their contribution was often relegated to a side note, gendered homely role, or condescendingly titled article in a larger volume focusing on the male experience.[1]

However, this collection brings to the fore the variety of roles – as combatants, prisoners, writers and politicians – played by women throughout Ireland’s revolutionary history.

Although the original volume was not purposely arranged thematically (it is somewhat structurally chronological), in its most recent foreword Marie Coleman identifies three such categorisations: women’s involvement in Irish rebellions (1641, 1798, 1916), literary focused essays (Annie M. P. Smithson, Rosamund Jacob, and Countess Markievicz), and lastly the more recent ‘Troubles’ in the North of Ireland.[2]

The multi-disciplinary background of the contributors gives this book a unique and interesting slant, eschewing the sometimes banal structure of mono-disciplinary works, and is perhaps its greatest strength. Using a wide range of sources, including archives and documents, newspapers and autobiographies, oral testimony and field research, the volume’s contributors examine sensitive and contested debates around women’s role in situations of war and conflict.

The volume’s contributors examine sensitive and contested debates around women’s role in situations of war and conflict.

Beginning with the less publicised participation of women in the nationalist uprisings of the 1600s and 1700s, and continuing to their active participation in the republican campaigns of the more recent twentieth century, the authors consider the evolving role of female militancy and the challenge this has posed to traditionally masculine imagery and structures; as well as the obstacles they faced in doing so.

For this reviewer, the most intriguing articles are those positioned in the earlier third of the volume. Andrea Knox reassessment of the involvement of Irish women in the rising of 1641 reveals a startlingly progressive society in which kinship, clan, and legal systems gave Irish women of landholding families significant political autonomy.

These so-called ‘Irish wives’ were frequently derided as ‘wild Amazonians’ by English authorities on account of the power that they wielded, particularly that which they exerted over their husbands. Making great use of the 1641 depositions, since digitised, Knox brings to life the female voice in a previously male-oriented passage of history. One could certainly gain scope for a research piece on the linguistic othering of Irish women based on the English reactions unearthed by Knox.

Continuing with the risings of 1798 and 1848, the second essay in the collection authored by Jan Cannavan traces the evolution of women’s rights. She contends that the reinvestigation of female participation in the aforementioned uprisings provides evidence which questions previously published theories regarding gendered pacifism. Cannavan’s essay reveals that not only were women active participants, particularly in the Wexford region in arming and fighting with the rebels, that this period marked a significant evolution in the sense of female nationhood.

Jan Cannavan’s argues that not only were women active, armed participants in the 1798 rebellion but that this also marked the evolution of female nationhood.

Co-editor Louise Ryan’s essay, the first of three literary based contributions, examines the portrayal of female revolutionaries through the prism of their male counterparts. Utilising the seminal memoirs of the Tan War poster boys Ernie O’Malley, Tom Barry, and Dan Breen (among others), Ryan found that ‘the male narratives emphasised the essential masculinity of republican men’, while downplaying the ‘essentially feminine’ supporting and non-combative roles of women.

The depiction of Irish women which emerges from these writings is one of sanctimony, homeliness, and nurture; all highly gendered characteristics.

At the time of writing, the now widely available Bureau of Military History witness statements where only in the process of initial release; and only then in hardcopy format by way of consultation at the National Archives. As Coleman notes, Ryan’s influential article laid the foundation for later work which benefitted from the subsequent release of the Bureau statements and its invaluable companion, the Military Service Pension statements, among other primary source documentation.[3]

Karen Steele’s article ‘Countess Markievicz and the politics of memory’ reappraises the enigmatic Countess’ literary contribution to the Irish Revolution (1912-1923), refocusing the spotlight on her intellectual merit, producing a notable riposte to Seán Ó Faoláin’s hatchet-job biography.

The third and final thematic section focuses on the conflict in the North of Ireland from 1969 to the Good Friday Agreement of 1998. Gender issues, prison experience, political activism, and female resistance all feature in the four articles which bolster this collection, the most innovative of which in this author’s view being Callie Persic’s article on the emergence of gender consciousness among a women’s group in a Ballymurphy housing estate.

This volume adds much in the way of understanding the vital role played by Irish nationalist women during some of the most seminal moments in Ireland’s history.

Persic’s source material for the aforementioned piece resulted from the author’s novel action research, which was conducted with the Belfast grass-roots group and airs a welcome plethora of female voices to an otherwise overwhelmingly male narrative. Bookending the collection, Margaret Ward gives a fascinating synopsis of the historiography of Irish women and nationalism, touching on many areas of success, while simultaneously offering plenty of food for thought with regard to prospective research topics.

With this collection of thought provoking essays the editors’ aim of contributing to a greater appreciation of Irish women’s engagement with and their role in Irish nationalism has most certainly been achieved.

This volume adds much in the way of understanding the vital role played by Irish nationalist women during some of the most seminal moments in Ireland’s history, while also offering a welcome scaffold upon which to build much new research and interpretation. It is essential reading for anyone interested in understanding this contribution and will intrigue the casual reader who may read on a chapter by chapter basis according to their own topics of personal interest.

Endnotes and references

[1] R. M. Fox, ‘How the women helped’ in Brian Ó Conchubhair (series ed.), Dublin’s fighting story, 1916-1921: told by the men who made it (Cork, 2009), pp 395-405.

[2] Marie Coleman, ‘Foreword to the New Edition’, in Louise Ryan and Margaret Ward (eds), Irish women and nationalism: soldiers, new women and wicked hags (Newbridge, 2019), pp ix-xx (xiii)

[3] See for example Eve Morrison, ‘The Bureau of Military History and female republican activism,1913–23’ in Maryann Gialanella Valiulis (ed.), Gender and power in Irish History (Kildare, 2008), pp 59-83.