Belfast’s Lost 1798 Burial Ground

Belfast witnessed a series of public executions of United Irishmen, but where were their remains buried? This article explores the handful of references to a 1798 ‘felons plot’ and looks at some of the reported discoveries of human bones around the city centre to try and relocate the burial ground. By John Ó Néill

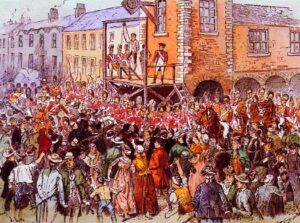

Over the course of 1797-1799 there were a number of public executions of United Irishmen in Belfast, with perhaps the best known being Henry Joy McCracken. At the time, individuals condemned to death also knew they (and their families and friends) would be subjected to additional punishments and humiliations.

These were likely to include public execution, having their head (or other body parts) cut off and displayed in public, the denial of formal burial or prescribed religious rites or an order that the remains be ‘handed to the surgeons for dissection’. The fate of McCracken’s remains became so storied precisely because they were given back to his family. But what of the fate of the other recorded executions in Belfast at the time, and where are they buried?

There were seven recorded executions of United Irishmen in Belfast in 1798, their burial place in some cases remains a mystery.

Belfast, as a centre for radical political thought in the 1790s was described as ‘…remarkable for its seditious practices…’[1]. While serious fighting took place in the adjoining counties of Antrim and Down during the 1798 Rebellion, Belfast was largely free of violence apart from executions, mainly public hangings. In the town centre, a court martial often sat in the Donegall Arms in Castle Place while the New Inn was often used to hold prisoners.

According to George Benn’s A History of the Town of Belfast (first published in 1823), there were seven executions of United Irishmen in Belfast in 1798-99. Based on contemporary newspaper reports the seven were William Magill, James Dickey, Hugh Grimes, Henry Byers and John Storey in June 1798, Henry Joy McCracken in July 1798 and George Dickson in May 1799. After Magill was condemned to death, the Belfast Newsletter reported that he “…was executed on a lamp-post opposite the Market-house, pursuant to sentence of Court Martial, for swearing soldiers from their allegiance.” [2]

There is no mention in the newspaper reports of what happened to Magill’s body. The United Irishmen had viewed Irish-raised regiments as a convenient source of trained soldiers and arms and repeatedly attempted to persuade soldiers to desert their allegiance to the British army and take the United Irish oath.

After James Dickey, Hugh Grimes, Henry Byers and John Storey were all hung on a temporary scaffold that was erected opposite the Market House, each was then beheaded and his head placed on a spike at the Market House. Dickey had requested, at the time of execution, that his body be given to his friends but it is not stated whether that happened. [3]

It also seems unlikely since press accounts state that their heads were to remain on the spikes at the Market House until 16 August 1798. Even then there is no mention of whether their bodies were given to friends. In 1799, George Dickson, the last of the seven, was hung opposite the Market House on 17 May, for treason and rebellion. There is no mention of either the display or disposal of Dickson’s remains.

But where were their remains interred?

As has been noted by Guy Biener, it was “…As a further humiliation, executed rebels were often denied burial in consecrated ground and their corpses were interred by the gallows, so that they could not be memorialised in accordance with funerary custom.”.[4]

As the gallows in Belfast had been erected at the Market House, burial there was seems impractical as it was in the middle of the commercial hub of the town. At least one set of human remains has been found near the spot, however.

‘Executed rebels were often denied burial in consecrated ground and their corpses were interred by the gallows’ Guy Biener.

On 1st May 1981, James Brannigan was repairing water pipes in front of No 6 Corn Market when he found some bones beneath the pipe. While working along the trench he encountered a skull and realised he had uncovered buried human remains. [5]

The bones were at a depth of over one metre from the modern surface, mainly overlain by masonry rubble but within the level of the estuarine muds that underly Belfast city centre. While the upper torso was reasonably well preserved, a report on the burial indicates that the key bones that might have identified death by hanging were actually missing.

The remains were that of 5 foot 6 inch adult male, 35-50 years old. The burial report by Ian Goddard from the Northern Ireland Forensic Science Laboratory notes that he considered the condition of the teeth unusual for someone who had a modern diet and so a date before the later nineteenth century was suggested. Apart from a reference to some broken animal bone, there is no mention of anything else associated with the burial that might suggest a closer date.[6]

The 1981 Corn Market burial is not the only known human remains from the vicnity of the executions.

In a paper in the Ulster Journal of Archaeology in 1861, a noted antiquary with an interest in Belfast’s early history, Canon John Grainger recorded the following discovery during work on replacing the culvert over the River Farset (which still runs along, and below, High Street):

“In Castle Place, a human skeleton as discovered. It appeared to be incomplete, but the whole may not have been observed by the workmen employed in the excavation. The portions distinctly recollected by the Clerk of the Works are, the lower jaw, a thigh bone and some ribs. The direction in which the remains lay seemed to be at about right angles to the cutting; and, as High Street runs East and West, this would be quite across the from the usual direction adopted in interments, and would countenance the supposition that the skeleton as that of a condemned person; which is also corroborated by the fact that executions did take place near the spot, namely opposite the old Market House, which occupied the place where Mr. McComb’s house now stands.”[7]

So, there are two least two known burials from this area, although neither is dated or had reported pathologies consistent with execution. And there are further human remains recorded from the vicinity.

A skull donated to Belfast Natural History and Philosophical Society by Robert Gunning, which was reportedly found “…when sinking the foundations of Mr Gunning’s buildings in Donegall Place.” Gunning’s buildings were constructed at the corner of Donegall Place and Castle Place in the early 1840s.

Yet another skull, reported to have been found at a depth of three feet in Castle Market in 1922, was more recently sampled and submitted for radiocarbon dating, returning a date around the 15th century AD.[8]

All of these locations – Corn Market, Castle Court on High Street, the corner of Castle Place and Donegall Place and Castle Market, circle the former Belfast Castle, itself of medieval date (similar to the radiocarbon dated skull). These are shown as red dots overlaid on the 1791 map of Belfast.

Another possibility is that some of the burials may be even earlier in date. In 1869, human remains were found when a sewer was being opened at the corner of Millfield and Francis Street. In 1903 evidence of further burials were identified off Cupar Street, again without any reference to artefacts or evidence of the burial rite that might help date the burial.[9] What these all have in common with the two burials in Castle Place is that all are located along the route of the River Farset. While none produced dating evidence, these burials may considerably predate the 15th century burial from Castle Market.

While this doesn’t preclude that the Corn Market and Castle Court burials may derive from executions (in 1798-99 or another date), although Grainger also states [10]: “… the regular place for such exceptional interments [executions] was at the ‘Long Bank’, behind Ann Street. Perhaps the skeleton may have been that of a suicide who had been buried (as customary) where four ways met; but this hypothesis would require a road to have existed corresponding to the present Castle Court, opposite to which opening the discovery was made…”.

The ‘Long Bank’ (‘The Bank’ on the 1791 map) was an embankment shown on seventeenth and eighteenth century maps of Belfast that extended out along roughly the same alignment as Corn Market, towards the south-east. This is marked on one seventeenth map as a ‘Sea Banck’. It was constructed at an unknown date to enclose the area on the west bank of the River Lagan, possibly to retain water to feed a tidal mill [the area later contained mill ponds and at least one contemporary landscape painting shows the long bank partially underwater]. The route of the Long Bank was subsequently obscured by the development of the Market district by Sir Edward May in the early 1820s.[11]

May’s association survives in the names of May Street, May’s Field, May’s Market and more. The earlier landscape of the area was largely obliterated by May’s regular, rectilinear street grid apart from one or two echoes. Cromac Street, which crossed the Blackstaff at the southern limit of the Market area, was an existing routeway that was so well established it had to be incorporated into May’s grid. The upper end of Cromac Street meets modern Victoria Street at an angle, just southwest of the former alignment of the ‘Long Bank’.

None of the historical maps that cover this area identifies a burial plot, nor is it referenced in street directories or valuations. However it is briefly mentioned in some later sources.

In 1910, F.J. Bigger noted in the Ulster Journal of Archaeology, that “The late Henry S. Purdon, M.D., records the burial of many ’98 victims in May’s fields, a short distance beyond the termination of May Street. Here was a narrow strip of ground, with a row of graves, known as the croppies’ burial ground.”.[12]

Purdon, like Mary Ann McCracken and others associated with events in 1798, was a key figure in Belfast Charitable Society, so his authority on a burial ground appears credible. A more recent, letter by W.S. Corken, to the Irish News (2 January 1971) about Henry Joy McCracken also states that “…the burial place of the ’98 men – his companions – was in May’s Market where the spot was known as ‘The Felons Plot’. The whereabouts of this sacred spot is unknown today in the Markets.” The name ‘Felons Plot’ given by Corken doesn’t feature in the Bigger/Purdon account and suggests there were, or are, other (now lost) references to this burial ground.

The location of a ‘Felons Plot’ somewhere in the Market is also consistent with a more general tradition of associating executions with the area. John Holness, a local historian and prominent unionist and Orangeman, gave a talk in Hewitt Memorial House in January 1930 on ‘Streets and Placenames in History’ with special reference to Belfast. In that he noted that “…Cromac Street had gloomy connections as the name originally meant ‘the way to the gallows’.” [13].

While not using direct quotes, Holness may be referencing an earlier source, the Belfast Naturalists Field Club’s Guide to Belfast and Adjoining Counties which provides an account of place names around the city, including “Ballycromoge – leaving a reminiscence in Cromac Street, and probably derived from cromog (a gallows). “A name indicative of public execution,” says Joyce (“Irish Names,” p.212), “is almost certain to fix itself on the spot, of which we have instances in the usual English names – Gallows Hill, Gallows Green, &c.”

Taking the Bigger/Purdon and Corken accounts, this missing ‘Felons’ Plot’ lies somewhere beyond the eastern end of May Street (which, at the time, was only built up as far east as Cromac Street), within May’s Market and along the former route of the Long Bank (see modern map with the position of the Long Bank shown).

A wider review of reports of human remains from Belfast city centre (such as around the former Belfast Castle) has identified a number of locations which appear to have been used as burial grounds but were never documented as such. Some of these may be seventeenth century in date, others may well be earlier. [14] Research on these is ongoing, along with other potential candidates to the ‘Felons Plot’.

Is it really believable that a 1798 burial ground in Belfast could be completely forgotten? In a letter from August 1798 (quoted in Robert Madden’s….), Mary Ann McCracken wrote that, “At this disastrous period, when death and desolation are around us, and the late enthusiasm of the public mind seems sinking into despair, when human sacrifices are become so frequent as scarcely to excite emotion, it would be a folly to expect that the fate of a single individual should excite any interest beyond his own unhappy circle.” [15]

Some former United Irishmen after 1798, tried to quietly obscure their former political allegiances, and never publicly marked the passing of those killed. One result was that, none of the nineteenth century maps indicate the actual position of a graveyard.

In the letter, she is articulating the isolation and anxiety felt by the defeated United Irish, and that preceded what Guy Biener has called ‘social forgetting’ the process by which memories of events like 1798 became obscured and confused. As Biener notes, some of those who had been active United Irishmen before 1798 subsequently tried to quietly obscure their former political allegiances, neither openly discussing events nor revealing their former sympathies by publicly marking the passing of those killed during the rebellion.

True to this ‘social forgetting’, none of the nineteenth century maps or other official documents indicate the actual position of a graveyard. Nor may there have been an attempt to formally mark the location as, as noted above, the space isn’t recorded on nineteenth century street directories or valuations.

Neither is there any suggestion in the courts or police reports of public or collective acts of commemoration at a site along the former route of the Long Bank. However, a small number of possible locations remain under consideration and it is hoped that further research may finally identify the location of the Felons Plot in the near future.

References

[1] This was the phrase used by the Monaghan Militia, when protesting its own loyalty after seventy-five of its own members admitted taking the United Irishmen oath and four were executed. See McSkimm, S. Annals of Ulster 1790-1798. (1906, Cleeland).

[2] Belfast Newsletter, 11 June 1798

[3] Belfast Newsletter, 29 June 1798. In his The Town Book of Belfast (1892, Dalcassian), Robert Magill recounts being told by a 104-year old witness that she remembered seeing the blackened heads on spikes in at the Market Hall (see p.324).

[4] See p.153 in Biener, G. ‘Severed Heads and Floggings: The Undermining of Oblivion in Ulster in the Aftermath of 1798.’ In The Body in Pain in Irish Literature and Culture (2016), .pp.77-97. See also Biener, G. Forgetful Remembrance: Social Forgetting and Vernacular Historiography of a Rebellion in Ulster (2020, Oxford UP).

[5] This account is based on a report in the Belfast Telegraph, 1 May 1981

[6] The Corn Market burial is included in Goddard, I. ‘Some Finds of Human Skeletal Material’, Ulster Journal of Archaeology, Vol. 44/45, (1981-2), p.206-7.

[7] See pp.115-6 in Grainger, J. ‘Results of Excavations in High Street’, Ulster Journal of Archaeology, Vol. 9 (1st Series), (1861), 113-119.

[8] See p.124 in the ‘Descriptive Catalogue of the Skulls and Casts of Skulls from various Irish Sources collected by the Late John Grattan, Esq.’ Proceedings of the Belfast Natural History and Philosophical Society (1873-4), p.121-126. Gunning’s buildings burned down in 1848 (see Banner of Ulster, 26 December 1848). This Castle Market skull was described as follows “Queen’s University, Belfast, found in 1922 and labelled as follows: — Human Skull found 6 feet 6 inches below street level and three feet below bed of marine shells in estuarine clay at Castle Market, Belfast, Oct., 1922. The skull is that of an adult male and is of the river-bed type.” It was subsequently sampled and radiocarbon dated to AD 1410-1500 (date quoted as 91% probability). For more see Delaney, M. And Woodman, P. ‘Searching the Irish Mesolithic for the humans behind the hatchets’, in Roche, H, Grogan, E., Bradley, J., Coles, J. And Raftery, B. (eds) From Megaliths to Metals, (2004, Oxford), pp.6-10. The skulls and some medieval finds in the vicinity are discussed in Ó Néill, J. ‘A Medieval Ring Brooch And Other Nineteenth-Century Discoveries At High Street, Belfast’, Ulster Journal of Archaeology, Vol. 65 (2006), pp.63-66.

[9] The discovery of buried human remains at the corner of Francis Street and Millfield was reported in the Belfast Weekly News, 9 October 1869, while the human remain found buried off Cupar Street human was reported in Northern Whig, 31 October 1903.

[10] See pp.115-6 in Grainger 1861.

[11] For more on the maps and May’s development in Belfast, see Gillespie, R. and Royle, S. Irish Historic Towns Atlas, No 12. Belfast, Vol. 1 to 1840. (2003, Dublin).

[12] F.J. Bigger ‘Notes’ Ulster Journal of Archaeology, Vol 16 (1910), p.96. For the Corken letter see Irish News, 2 January 1971.

[13] Holness’s talk was reported in the Belfast Telegraph, 25 January 1930. See also p.143-4 of Belfast Naturalists Field Club Guide to Belfast and Adjoining Counties (1874, Belfast).

[14] See Ó Néill, J. New Burying Ground and Burial in Nineteenth Century Belfast in Olwen Purdue (ed) First Great Charity of This Town: Belfast Charitable Society and its Role in the Developing City (2022, Irish Academic Press), pp.180-199.

[15] Letter as quoted on p.501 in Robert Madden’s The United Irishmen: Their Lives and Times (1843, Madden). See also Biener 2016; Biener 2020.