The death of Thomas Keating: A Civil War Killing in Waterford

By David Prendergast

On April 11th 1923, Thomas Keating, the 30-year-old guerrilla commandant of the Waterford IRA 2nd Battalion, was trekking through the foothills of the Comeraghs to his family’s farm in Kilrossanty.

Unfortunately for him, the mountains of South Tipperary and West Waterford were swarming with up to one thousand National army soldiers, seeking to eliminate the few remaining shards of the shattered IRA resistance. The day prior, April 10th, the military had shot and killed Liam Lynch, Chief of Staff of the IRA forces, in the Knockmealdowns.

Keating had been in the South Tipperary area as part of the wider security detail for the Executive meeting that Lynch was trying to reach. Following the body blow of Lynch’s death to the Anti-Treatyites, Keating retreated to Sliabh gCua where he sheltered alongside his O/C Mick Mansfield[1]. From there, the pair parted ways, and Keating went to a safe house at Ryan’s of Knockalisheen in Fourmilewater[2]. He planned to begin his journey home the following morning.

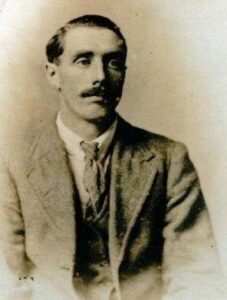

Thomas Keating, leader of the anti-treaty IRA guerrillas in West Waterford, was shot in the Comeragh mountains on April 11, 1923.

Keating’s home during the War of Independence had been a key safehouse and communication centre in the West Waterford area. The family were a staunch Republican outfit as their father, Michael, had been arrested and briefly jailed in Kilkenny for Land League membership in 1881. All of Keating’s eight siblings had taken part in varying degrees of activities against the British but it was Keating’s younger brother Pat that had been a true force of reckoning.

Such was the prominence of Pat’s role in the majority of Waterford IRA attacks on British forces, there was a significant reward was offered for his capture: £1,000 alive or £400 dead.[3] Because of this, the family home where Keating still resided was a continuous target for British raids and harassment. When Pat was killed in the Burgery Ambush in March 1921, he was buried three times within a two month period to keep his body from falling into British hands.

Following Pat’s death, Keating stepped into his brother’s role as commandant of the Comeragh Battalion. When the country slipped into a Civil War, due to the celebrity of the family’s name in West Waterford, and their steadfast determination to continue fighting and win the Republic that Pat had died for, Keating became a high value target for Free State forces in the area. When he was finally tracked down and snared in the final weeks of the conflict, his controversial death, which remains contested today, would mark one of the darkest chapters of the conflict in Waterford.

War Weary

Like all his fellow IRA comrades in April 1923, Thomas Keating was war-weary after a brutal winter. Public sympathy had receded, food became harder to source, and home was more and more challenging to visit. Most nights were spent out in the open with nothing but disused cattle feed sacks as blankets.

Not twelve months before, Keating had enjoyed a heavily fortified position at the old famine-era workhouse in Kilmacthomas. The site consisted of a dining hall, a chapel, a two-story hospital, a three-story dormitory, and two single-story buildings at the site entrance[4].

Keating had occupied the workhouse at Kilmacthomas until August 1922, after which he had been on the run in the mountains.

It had been designed to house up to 600 people, and thus it was an excellent military position to command.

He managed to hold it until late August, when he finally abandoned it due to mounting pressure coming east from Waterford city and west from Dungarvan. Despite orders from GHQ to burn all abandoned headquarters, Keating left the workhouse intact following pleas from the local priest and convent[5]. This was a sign of his mild character in the early days of the Civil War, before the bitter phase of executions and reprisals got a stranglehold on the war.

In just a few short months, he would threaten to burn down a local dance hall[6] and become a suspect in the burning of Protestant-owned mansions, Comeragh House and Rockmount House (the former destroying all personal papers of the explorer John Palliser’s expedition that mapped Western Canada for the British government between 1857-60)[7].

Refuge in the mountains

Following his withdrawal from the Kilmacthomas workhouse, Keating took to the nearby Comeragh mountains. He had lived and worked there as a farmer until his younger brother Pat’s death in the ‘Tan War’ dragged him into the armed struggle for a Republic. Here, Keating waged a largely spasmodic guerrilla campaign against the National army. Intelligence reports dated October 6th 1922 noted that his column had all but been destroyed due to mass arrests[8].

Keating was nearly killed in late October when he was recognized after dark on the streets of Kilmacthomas. However, the National army soldier’s rifle jammed six times during the resultant chase[9]. Though increasingly isolated, Keating and his remaining men turned their attention to a hybrid war of propaganda and critical infrastructure attacks.

December 1922 was a particularly momentum-filled month for Keating, which saw trains derailed and burned at Durrow (twice), Ballyvoile and Kilmeadon, in addition to the felling of trees and mining of roads[10]. Safely harboured in the Comeraghs, Keating’s knowledge of the mountains from his years as a farmer and sheep herder made him a challenging foe to anticipate and apprehend.

Journey Home

On April 11th 1923, Thomas Keating began his journey home. Passing through Bleantis, Kilbrien, he met up briefly with fellow Active Service Unit commandant Jack O’Mara and Volunteer Tommy Cullinan. By around 11:00 am at Skeheens, he encountered his sister Marcella[11].

An active member of Cumann na mBan, Marcella was in the mountains partaking in intelligence work as the Free State army continued its roll through the Comeraghs from Lismore to Rathgormack[12].

Skeheens offered a direct route across the mountains to Keating’s home in Kilrossanty. At this point in his journey, he was roughly ninety minutes from home. Yet instead of continuing with Marcella, he gave her a garment to carry back for him. He had one more job to do, it seemed. It was then he veered off course from Kilrossanty.

By mid-afternoon, he was in Coolnasmear, a small townland on the outskirts of Dungarvan, at the home of his cousin Catherine Walsh and her husband, James[13]. In his company at this point was Patrick Landers, a veteran of the Great War and War of Independence, and currently serving as an IRA dispatch carrier[14].

Leaving his cousin’s house, Keating continued alone on foot, now seemingly aiming to once more get over the mountains and back home to Kilrossanty. However, ascending the rising foothills of Coolnasmear that slowly build toward Cruachan Hill, he was felled by a single bullet near a place called the “Wood Road[15].” A party of National soldiers had been waiting for him, and he was gunned down immediately upon coming into sight and captured without a struggle.

The fatal shot

The shot that brought down Thomas Keating was reportedly fired from roughly half a mile away, or 880 yards[16]. It was a long shot but not impossible, fired from a downward trajectory at a moving target. The rifle was likely a Lee Enfield with .303 ammunition, which was the standard weapon of pro-Treaty forces. This weapon had a maximum range of 2,000 yards, but its effective range was 550[17].

An 880-yard range also required the shooter to account for a 325-inch drop[18]. In other words, this was a challenging shot to pull off intentionally. That said, according to weapons expert Kieran McMullen, it could be made by a well-trained marksman[19].

Keating was shot from long range, the bullet entering his hop and exiting through his abdomen.

The bullet entered Keating through his left side, struck his right hip bone, and exited the front of his abdomen. Given the shot was fired 330 yards outside the rifle’s effective range, the bullet’s velocity would have been reduced by the time it struck Keating, and this caused it to flatten out when hitting his hip bone.

Wartime ammunition used compressed paper, wood fibre, or ceramic in the nose. In that sense, it tended to fold in half when it hit something reasonably solid. This would cause the lead rear to separate from the copper jacket, sending it on its own path through the body[20]. This is what happened in Keating’s case and the deformed copper jacket caused three lacerations to his intestines as it ricocheted through his stomach.

When the bullet struck, Thomas Keating may have felt like he had been suddenly hit with the stroke of a cane or experienced an intense heavy blow[21]. Every shooting victim reacts differently, and the amount of pain he felt would have depended on a degree of factors. These include the kind of wound left by the bullet and his emotional and physical state at the time.

Keating was shot sometime before 3.00 pm, yet, it was after 8.00 pm before he was seen by a medical doctor.

When Ernie O’Malley was shot multiple times by Free State troops in November 1922, it felt like being hit by a “heavy rock” and a “sledgehammer[22].” That said, when the stomach or an organ is wounded (in Keating’s case, both), pain is usually trumped by stress and alarm at the injury. More commonly, this is known as shock. Generally, the more serious the wound, the more significant the shock[23]. The gravity of Keating’s injury means he would have almost immediately gone into shock upon being shot down.

With stomach and organ wounds, the body’s transition to crisis mode is fast. Keating’s abdomen would have swelled and become irritable, tender, and inflamed[24]. While a bullet wound to the stomach has an unfavourable prognosis, Keating was not in a position from which he couldn’t recover. Still, to have any hope of surviving, he would have to be seen by a doctor directly after the infliction or within an hour or two at most[25]. Past that timeline, it is a zero-moment point – the point of no return. Sadly for Keating, it was (conservatively) a minimum of at least five hours before a medical doctor could see him.

Following his capture, Thomas Keating was transported to a nearby farmhouse belonging to a Wade family. Here he was given makeshift medical aid by the parish priest of Kilgobinet, Fr. Michael Burke[26].

Critically, rather than next be transported to Dungarvan hospital, a mere eight kilometres away, Keating was to be paraded as a prisoner on a celebratory pub crawl across West Waterford by his captors. Their drinking tour included stops at Bohadoon, Brown’s Pike, Millstreet and Cappoquin. Upon entering Cappoquin, Keating was tied in a standing position on the back of the Crossley tender to be made an example of[27].

Keating was shot sometime before 3.00 pm. Yet, it was after 8.00 pm before he was seen by a medical doctor, Dr William White, in Cappoquin. Dr Michael F. Moloney later joined this physician, and an ambulance was sequestered to move him immediately to Dungarvan hospital.

In the late hours of April 11th, Keating was finally admitted to Dungarvan hospital. A journey of approximately eight kilometres had instead taken roughly 69 kilometres. This was the end result of the National soldiers’ drinking spree. Dr John C. Hackett, who would fruitlessly operate on Keating, told the medical inquest into the death that he was in a “very collapsed condition” when he was finally brought in[28].

By one o’clock on the morning of April 12th, Keating was dead.

A problem of sources

The opening section of this article, detailing Thomas Keating’s journey to his doom in Coolnasmear, is based on the oral history of the event as recorded by Keating’s nephew John Quinlan. It was pieced together by Keating’s siblings in the event’s aftermath.

Aside from newspaper reports on the medical inquest into Keating’s death, there appear to be only seven other existing primary source documents referencing the circumstances around the shooting of Keating. However, all these only amount to general summaries and, combined, average a mere 36 words.

These include military service pension applications from Catherine Walsh, Patrick Landers and Thomas Keating (submitted posthumously by his family), army reports by Lt. Michael Thomas Baldwin and Captain Thomas Joseph Stokes, a Bureau of Military History statement by Mick Mansfield, and Lena Keating’s (Thomas’ sister) unpublished family history.

So, aside from John Quinlan’s oral family history of the shooting, that leaves just one major source of primary documents that extensively deal with the shooting of Thomas Keating to compare it against – the newspaper accounts by the Cork Examiner and Waterford News (the only papers that report on the subject in any significant detail). These present the Free State version of events that led to the shooting and capture of Keating, as testified by two unnamed National soldiers at the medical inquest into his death.

The National Army’s account of Keating’s shooting claimed that he opened fire on them and was afterwards hit by a ‘blind shot’.

The Free State’s case was essentially this. A party of four soldiers uncovered Keating at a safehouse in Coolnasmear. Upon being discovered, Keating fled with Landers into the nearby hillside. He was called on to surrender but met this order with fire from a Peter the Painter handgun (fitted with a hollow wooden stock to enable it to be positioned as a rifle) and then disappeared into a rocky gulley. Eventually, he was flanked by a second nearby party of soldiers and dropped by a un-aimed, blind shot[29].

Some minor differences exist between the two versions. For instance, the National soldiers state that Keating was uncovered at a safehouse and was chased alongside a companion. In contrast, Quinlan’s oral history says that Keating had left the safehouse and was alone. Those aside, the major difference between the versions is the most chilling. In one, Keating is shot cleanly in a fair gunfight that he initiated, having been given multiple occasions to surrender. In the other, he is cut down in cold blood by a marksman’s bullet without warning.

‘In execution of their duty’

So, how does one decipher where the truth lies? One thing of interest regarding the Free State version is that it contains one obvious glaring mistruth. Testifying before the jury, the superior officer in charge of the band of soldiers that shot, captured and delayed medical assistance to Thomas Keating for a minimum of five hours states: “I did everything I could for the man[30].” As this is untrue, it casts a large shadow over the remaining testimony.

The circumstances of the Free State evidence also weigh heavily against its favour of being the whole truth. The two National soldiers testifying were doing so in front of a jury that was seeking to determine whether the military should be found guilty of any wrongdoing in the death of Keating.

As Anti-Treaty TDs elected in June 1922 boycotted the Dail, and the press was heavily censored, the legal avenue of medical inquests into the death of IRA Volunteers was one of the few weapons at the IRA’s disposal to highlight Free State killings, such as that of Keating[31]. Should a National soldier be found culpable of murder in Keating’s death (i.e. deliberately killing an unarmed man who posed no threat to them), they would be committed to stand trial before the criminal courts – a legal consequence of a verdict of ‘murder’ by a jury at a coroner’s court.

Though such cases were rare – most juries in contested cases returned a verdict of ‘shot during execution of military duty – they were an avenue of hope for republican families. For example, in November 1923, a Free State soldier in Mayo was charged with the March 1923 murder of an anti-Treaty prisoner, Nicholas Corcoran through the victim’s medical inquest (that said, the soldier, a Sgt. Boyle, would eventually be acquitted)[32].

That said, the system was rigid and only sought to uncover the victim’s identity and the medical cause of their death. For example, at the medical inquest into the death of Harry Boland in 1922 (who, similarly to Keating, was denied medical treatment after being shot and taken into Free State custody), the family’s solicitor refused to call any witnesses to confirm the identity of Boland[33]. This strategy was to prolong the hearing and force the coroner to call witnesses, allowing the Boland’s solicitor to explore more evidence.

This was not a tactic deployed by the Keating family’s solicitor, John F. Williams of Dungarvan. Keating’s younger brother Michael identified the body[34]. Nor is it known if Williams disputed the National soldiers’ testimony. Nor do the newspaper reports mention if any witnesses were presented to dispute this exact narrative of the army’s shooting of Keating.

An attempt was made to locate the original coroner’s report resulting from the medical inquest. However, it could not be found. A search of the Military Archives and the National Archives proved fruitless. An enquiry to Waterford city and county archivist Joanne Rothwell confirmed that Co. Waterford coroners’ reports remain unlocated today[35].

Additionally, Rothwell advised that she had previously searched the courthouse archives of Waterford, Lismore, Dungarvan and Youghal. She has also contacted previous coroners. Thus, at this time, they appear lost to history. An attempt was also made to locate any information the Williams firm may still hold on record from the inquest. However, this too ended in a cul de sac.

For his part, John Quinlan says that Keating’s siblings requested a copy of the medical inquest from the coroner’s court multiple times and even tried to have another inquest opened for their brother, but all to no avail. The family never received a copy of the report, leading them to believe it had been destroyed[36].

In the end, the jury at the coroner’s inquiry ruled that Keating had died as a result of shock, consequent of his bullet wound, and returned a “Not Guilty” verdict for the army, declaring that he had been fairly killed in battle[37].

As for Quinlan, he says: “My version, and the Keatings’ version – this is the true version[38].”

Memory

Sadly, Free State atrocities were a common thread at this stage of the conflict. While a total of eighty-one IRA Volunteers were officially executed during the war, many more were unofficially disposed of through means of kidnapping, being shot after they had surrendered, being shot under interrogation, or being tied to landmines and blown up. In a sense, Thomas Keating’s denial of appropriate medical care was just another means of conducting an unofficial execution.

Following Keating’s death, his body lay in rest at St Mary’s church in Dungarvan. Due to the Catholic Church’s hard-line stance against the IRA, only one Mass was permitted for Keating. John Quinlan recalls that Keating’s mother was allowed only ten minutes with her son’s body before being taken away by the military[39].

However, in an early sign of reconciliation between the Free State and IRA, the newly formed Civic Guard mounted a guard of honour as Keating’s coffin exited the church. Keating was buried in the republican plot in Kilrossanty churchyard, alongside his brother Pat, John Fitzgerald and fellow Civil War victims John Dobbyn and John Walsh.

In an early sign of reconciliation between the Free State and IRA, the newly formed Civic Guard mounted a guard of honour as Keating’s coffin exited the church

At the end of the month, just over two weeks after Keating’s death, Frank Aiken was elected Chief of Staff of the IRA. Aiken immediately ordered a suspension of offensive operations and handed the reins of authority over to Éamon de Valera to pursue peace negotiations with the Free State government. Keating came that close to surviving the conflict.

Sadly, Keating’s death did not bring an end to the Civil War experience for his family. Shortly after his death, a group of National soldiers occupied their neighbour’s house and physically prevented the Keating family from leaving their home for several days[40]. After this incident, further hurt was visited upon the family when it was their turn to hold the station Mass in their house. They were unexpectedly skipped over for this and were informed by the priest that “he could not hold the Station in a house used for harbouring rebels[41].”

A muted story

Thomas Keating was 30 years old at the time of his death. Pat McCarthy has likened him to Liam Lynch: “In Waterford, Keating embodied the flame of resistance as much as Lynch had done on a national level[42].”

When concluding the impact of Keating’s death on the family, Lena Keating wrote: “To the family this second death was even more tragic than the first. Pat had been shot by the British but Thomas had now been killed by Irishmen, some of whom had been former colleagues and had been given refuge in Thomas’s own home in Comeragh[43].”

John Quinlan summarises the ultimate tragedy that was the Irish Civil War when commenting on the prolonged nature of Keating’s death in Free State custody: “That was an awful atrocity to do to a man that you’d fought with twelve months ago[44].”

Unfortunately, due to the atrocities of the Civil War, and the bitterness that remained in Irish society following the conflict’s conclusion, for decades afterwards Keating’s larger story has mostly been muted. Instead, his contribution to Ireland’s fight for freedom has been reduced to a footnote regarding his death. This is in sharp contrast to his brother Pat’s role in the War of Independence. The Bureau of Military History’s objective was only to gather first-hand witness accounts from 1914 to 1921. Therefore, while the BMH is an excellent resource to help craft a complete picture of Pat’s heroics during the War of Independence, for Keating, whose main armed action took place in the Civil War, and who died in such contested circumstances, it is near absent.

References

[1] Interview with Brendan Mansfield, 11 Feb. 2023.

[2] Interview with John Quinlan, 16 Sept. 2022.

[3] MA MSPC 1D220A, Thomas Keating.

[4] J.G. Crotty, ‘Kilmacthomas Union: the administration of Poor Law in a County Waterford workhouse, 1851-1872’ (BA, UCC, 2007), p. 6.

[5] Tommy Mooney, The Déise divided: a history of the Waterford Brigade IRA and the Civil War (2021), p. 107.

[6] MA CW/OPS/10/05, box 27, report from Area IO, Kilmacthomas, 12 Dec. 1922.

[7] Emily Ussher, ‘The true story of a revolution’, https://www.ireland.anglican.org/cmsfiles/images/aboutus/AOFTM/2022/April/RCB_Library_MS70.pdf (accessed 24 Aug. 2022).

[8] Mooney, The Déise divided, p. 118.

[9] CW/OPS/10/05, box 27, report from Area IO, Kilmacthomas, 24 Oct. 1922.

[10] E.g. MA CW/OPS/10/05, box 27, report from Area IO, Kilmacthomas, 8 Dec. 1922.

[11] Interview with John Quinlan, 16 Sept. 2022.

[12] MA MSP34REF47312, Marcella McCarthy.

[13] Interview with John Quinlan, 16 Sept. 2022.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Interview with John Quinlan, 16 Sept. 2022.

[16] Cork Examiner, 17 Apr. 1923, p. 8.

[17] Andrew Nahum, Paths of fire: the gun and the world it made (London, 2021).

[18] Email from Kieran McMullen, 14 Sept. 2022.

[19] Ibid.

[20] Ibid.

[21] Sir Thomas Longmore, A Treatise on Gunshot Wounds (San Francisco, 1862), p. 44.

[22] Ernie O’Malley, The Singing Flame (Cork, 2012), p. 238.

[23] Ibid, p. 45.

[24] Ibid, p. 95.

[25] Park Roswell (ed), A Treatise on Surgery by American Authors, Vol. 2 (London, 2017), p. 343.

[26] Seán and Síle Murphy, The Comeraghs, gunfire and civil war: a history of Waterford’s Déise Brigade IRA, 1914–1924 (Dungarvan, 2020), p. 157.

[27] Interview with John Quinlan, 16 Sept. 2022.

[28] Cork Examiner, 17 Apr. 1923.

[29] Ibid.

[30] Ibid.

[31] Seán Enright, The Irish Civil War: law, execution and atrocity (Newbridge, 2019), p. 12.

[32] Dominic Price, The Flame and the Candle: War in Mayo, 1919-24 (Cork, 2012), p. 257-258.

[33] Enright, The Irish Civil War, p. 12.

[34] Cork Examiner, 17 Apr. 1923.

[35] Email exchange with Joanne Rothwell, 17 Feb. 2022.

[36] Interview with John Quinlan, 16 Sept. 2022.

[37] Cork Examiner, 17 Apr. 1923, p. 8.

[38] Interview with John Quinlan, 16 Sept. 2022.

[39] Ibid.

[40] Walsh, ‘The Keatings of Comeragh’, p. 8.

[41] Ibid.

[42] Pat McCarthy, The Irish Revolution, 1912–23: Waterford (Dublin, 2015), p. 120.

[43] Walsh, ‘The Keatings of Comeragh’, p. 8.

[44] Interview with John Quinlan, 16 Sept. 2022.