The Man Who Saved Howth – sea mine defused in 1946

By Terence O’Reilly

By Terence O’Reilly

In the cold pre-dawn hours of the 12th March 1946, the village of Dalkey was suddenly rocked by a massive explosion on its seafront. The sky was lit by a brilliant blue flash visible from Drumcondra and the thunderous blast was heard in Clontarf. Hundreds of windows were shattered and tiles stripped from roofs. With daybreak, the villagers surveyed the devastation.

Over two hundred buildings were affected, ranging from broken windows to structural damage. Mercifully there were no human fatalities. Soon windows were being boarded up and debris being cleared from the streets.

A small group of Irish army officers were noticed at the shoreline under the Cliff Castle Hotel, grimly observing the damage done to the Maiden Rock that had absorbed the worst of the blast. For them, the cause of the explosion was obvious. During the Second World War, which was termed ‘The Emergency’ in the Irish Defence Forces, the Royal Navy had laid over six thousand naval mines in the Irish Sea. Stormy weather could separate them from their moorings and they would drift into shipping lanes.

Many were intercepted by the newly formed Marine Service, and by the vessel ‘Fort Rannoch’ in particular, who would sink the lethal devices with accurate rifle fire. Many however made it to the Irish coast, where most were dismantled or detonated by specialist teams of the Army Ordnance Corps. In January 1941 alone, nearly thirty mines landed on the south east coast; four soldiers were killed by one exploding on Cullenstown Strand. Thirty three civilians were killed during the war years by such devices exploding against rocks or cliffs, including a lighthouse keeper on the Tuskar Rock.

Ten months after the surrender of Nazi Germany, many mines were still in place and were often set adrift in bad weather. The standard British naval mine at this time contained a five hundred pound charge of Amatol, a lethal mix of TNT and ammonium nitrate. Dalkey had been extremely lucky.

That night, another naval mine was washed ashore at the coastal railway line near Kilcoole, County Wicklow. Rail services on the east coast were suspended and a mine disposal team from Portobello Barracks (later renamed Cathal Brugha Barracks) in Dublin was tasked with dealing with the mine. Leading this unit was Captain Patrick McCourt. A graduate of UCD in 1935, he had volunteered for the Defence Forces during the 1940 call to arms and completed the exacting Ordnance Officers Course.

Mentored by the redoubtable Commandant Martin Kelly, McCourt opted to serve on in the Army Ordnance Corps after the conclusion of The Emergency in 1945. The highly trained mine disposal team toiled throughout the night and it was not until the early hours that the mine was finally disarmed. McCourt thankfully returned to his home in Howth at five in the morning and was soon fast asleep. It was the morning of 13th March 1946.

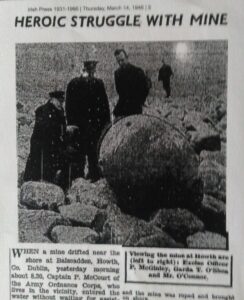

Captain McCourt’s sleep was short lived. At eight-thirty he was awoken by local Gardaí knocking urgently on his door. They had grim news: a third mine was at that moment rolling in the surf on the East Pier.

McCourt dressed hurriedly and pausing only to grab a small toolkit, raced to the scene and assessed the situation. Unlike the other two mines, this one was within thirty metres of the houses on Balscadden.

Furthermore, the mines five hundred pound Amatol charge had a blast range that put Abbey Street and Harbour Road in danger. Although Gardaí were already bravely evacuating the inhabitants of nearly sixty houses to a place of safety, an explosion could have taken place any second with consequences more devastating than the North Strand Bombing of May 1941. Clambering across the slippery rocks, McCourt waded waist-deep into the freezing water and began grappling with the mine.

Already sleep-deprived, he was soon exhausted from physically restraining the big device in rough water and hypothermic from the waves that regularly submerged him. But after thirty minutes of struggle, he succeeded in unbolting the top cover and defusing the mine.

Only the immediate danger was past – the detonator remained operative and was physically impossible for one man to remove. It was at this time that McCourt was joined in the water by the rest of his team from Portobello Barracks. It took this unit three further hours to secure the naval mine, lift it above the shoreline and remove the detonator. The mine was declared safe and later dismantled. At noon the anxious townspeople were told that they could return to their homes.

McCourt soon received wide acclaim from such organisations as the RNLI and a few weeks after the incident, his grateful neighbours presented him with a handsome gold watch at a ceremony at Howth Parish Hall. For his part, McCourt said that “he had only done his duty as a soldier.”

A keen hillwalker and swimmer, Patrick McCourt was to spend the rest of his life in the Army. After reaching the rank of Lieutenant-Colonel, he died in January 1975 just a short time before his retirement date. His obituary spoke of an expert and respected officer who was good company and could be “flexible and compassionate where a case of human weakness or personal misfortune was concerned. Many are the stories told of his “‘helping lame dogs over stiles.’ And the lame dogs never forgot his kindness.”

In an annual report being compiled in the same month of the near disaster in Howth, Defence Forces Chief of Staff Lieutenant General Daniel McKenna commented:

I should like to record my appreciation of the invaluable work done by ordnance officers during the past six years in the salvaging, dismantling and destruction of sea mines as they approached our coasts. During that time, practically a thousand mines have been rendered harmless by these officers – a task which, in each case, was not without its element of personal risk – and in most cases the work had to be carried out under very unfavourable conditions. The fact that in no case of dismantling was there loss of military or civilian life is sufficient testimony of the efficiency and thoroughness with which these officers and their staffs carried out their onerous and important duties both day and night as the presence of these mines were reported off our shores.

Sources:

THE IRISH DEFENCE FORCES 1940-1949 (The Chief of Staff‘s Reports) Michael Kennedy & Victor Laing Irish Manuscripts Commission (2011)

Donal McCarron, Step Together, Ireland’s Emergency Army, Irish Academic Press 1999

An Cosaintóir – Irish Army newspaper

(Evening Herald) Mine Explosion Heard Across Bay 12 March 1946, Mine Alarm in Howth 14 March 1946, 219 Houses Damaged 23 March 1946, Howth Gift for Army Officer 6 April 1946

(Irish Press) Dalkey Rocked by Explosion 12 March 1946, Heroic Struggle with Mine 14 March 1946