Belfast Republicans and the Treaty Split of 1922 – Part 2

By Kieran Glennon

Part one of this article (see here) analysed the initial reaction of the Belfast IRA to the Treaty –

just like other IRA units around Ireland, they split on the issue and while the majority remained loyal to the pro-Treaty leadership in IRA General Headquarters (GHQ), a substantial minority did not, but instead gave their allegiance to the anti-Treaty IRA Executive.

Resentment and even violence built up between the two factions in Belfast and the pro-Executive side made an abortive attempt to intervene in the Civil War in the south after hostilities commenced at the Four Courts in Dublin.

Here, the focus switches to those who, while also opposing the Treaty, stayed with the pro-Treaty GHQ in Dublin and participated in the Civil War.

Moving south: the Curragh

With both the Northern Offensive and the arson campaign in Belfast having failed, internment beginning to have an impact and hostilities with the pro-Executive Brigade getting progressively worse, the pro-GHQ Brigade in Belfast was in a desperate position by late June. Henry Crofton was Quartermaster of its 2nd Battalion:

Q: Things were in a pretty bad state after the big round-up in May ’22 up there?

A: Yes.

Q: Was there any real organisation functioning?

A: Yes. That Battn. was functioning. I kept the 2nd Battn. going, myself and Seamus Timoney …

Q: Were you actually discharging the function of Battn. Q.M. on 1st July ’22?

A: Yes, I was.”[1]

Crofton was arrested on 8th July: “On that date I was actually getting ready dumping the guns in Belfast to go to Dublin to take part against the Irregulars as all my Batt. Officers & Brig. & Div. officers did a few days after.”[2] His arrest had dire consequences for the IRA: documents found in his possession led the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) to search a hall in Rathbone St in the Market area – this turned out to have been the headquarters of the Belfast Brigade since before the split.

With internment in force in the North, many Belfast Volunteers fled south to the National Army camp at the Curragh in August 1922.

There, as well as arms, ammunition, explosives and stolen police uniforms, the RUC found a treasure trove of documents. The IRA had been lucky enough to have in its ranks a number of machine-gunners who had been trained in the British Army, but the RUC was even more fortunate that the IRA had kept a written list of those men’s names and addresses. Within twenty-four hours, the eight houses on the list had been raided – at three, the men named no longer lived there, but the other five men were promptly interned. Another document named the officers of all the companies in the 2nd Battalion, specifying which of them was or wasn’t working.[3]

This intelligence victory for the RUC increased the pressure on the already faltering pro-GHQ Brigade. Meanwhile, morale among the nationalist population was crumbling in the face of the increasing levels of attacks by the RUC and Ulster Special Constabulary. On 20th July, a clearly despairing Séamus Woods, O/C of the pro-GHQ 3rd Northern Division, reported to GHQ:

“Unfortunately, however, the anti-Irish element of the population are taking advantage of the situation, and are giving all possible information to the enemy. Several of our dumps have been captured within the last few weeks, and in practically every case the raiding party went direct to the house … many Officers and men are forced to go on the run necessarily in their own areas. They find it difficult to get accommodation with the people now … The men are in a state of practical starvation and are continually making application for transfer to Dublin to join the ‘Regular Army.’”[4]

Some had not waited for permission to go south. Among the documents seized in the Rathbone Street raid were receipt books which included some cash amounts issued with no apparent reason, either by Crofton or by the 2nd Battalion Adjutant, Joe McPeake. Pat Thornbury, the O/C of the pro-Executive 3rd Northern, had a withering opinion about these payments:

“The QM of the 2nd was actually dishing out the funds to men of the Free State Army although between March and July they will be counted here as having service. Their service was recruiting. Someone said it was like a pilgrimage to Lourdes, getting in all sorts. And the QM of the 2nd Battalion was the man who paid their fares to Dublin. He joined the Free State Army.”[5]

On 27th July, Woods sent another plea to GHQ:

“… the Divisional staff feel they cannot carry on under the circumstances, nor can we in justice ask the Volunteers and people to support us any longer when there is not a definite policy for the whole Six County area and our position as a unit of the IRA under GHQ defined.”[6]

A meeting took place a few days later, on 2nd August 1922 in Dublin, involving Woods and Roger McCorley, as well as officers from the 2nd Northern, along with Michael Collins, Richard Mulcahy, Eoin O’Duffy and other senior GHQ officers. At this meeting, it was decided:

(1) That all IRA operations in the Six Counties would cease forthwith.

(2) That men who were unable to remain in the Six Counties would be handed over a barrack at the Curragh Camp, where they would be trained under their own Officers to such tactics as would be applicable to the nature of fighting in the Six Counties.

(3) That they would not be asked to take any part in any activities outside the Six Counties.”[7]

In short, southern military facilities would be granted to northern IRA men on the run but, even though by this stage the Civil War was underway in the south, it was not envisaged that the Provisional Government would tap this potential source of manpower for its own armed forces who were then engaged in putting down anti-Treaty resistance.

With this, the trickle from the north became a stream and by late August, the Curragh was home to 379 members of the 2nd and 3rd Northern Divisions, ostensibly training for a new campaign in the north.[8]

That campaign never materialised. By the late autumn of 1922, Collins was dead and the Provisional Government had decided to adopt a peace policy towards the Unionist government in the North.

However, it was not until late October that this decision was communicated to Woods, Mulcahy curtly informing him that “the policy of our Government here with respect to the North is the policy of the Treaty.”[9]

This sounded the death-knell for the pro-GHQ Belfast Brigade. One of its remaining officers in the city, Joe Murray, stated that:

“During the month of October 1922 I received instructions from the Brigade to close up our headquarters and offices and to find a permanent dump for arms and equipment and to consider that the war was postponed until we would see what would come out of the Treaty.”[10]

Staying in the south: the Free State Army

With the idea of a second northern offensive now permanently abandoned, those in the Curragh had fresh decisions to make – McCorley noted, “We held a meeting with the Divisional O/Cs and Staffs and we decided that any man was free to go where he wanted, either to go home to the North or join the Free State Army … There was no pressure brought to bear on us whatsoever.”[11]

Some of those who opted to go back north felt that the Provisional Government had behaved shabbily towards them: “Those who returned complain bitterly of their treatment, many of them tramped home from Dundalk, others travelled by train without tickets as the Free State did not pay their fare beyond Dundalk.”[12]

It was initially thought that the men in the Curragh would be retrained and sent back to the North, but October 1922 these polices were abandoned by the Provisional Government.

Frustrated by inaction, feelings among those in the Curragh had been running high even before Mulcahy’s abrupt memo to Mulcahy; Ernie O’Malley, who was the anti-Treaty IRA’s O/C Northern and Eastern Commands, wrote to Chief of Staff Liam Lynch:

“I am in touch with a man in the Curragh and I have informed Aiken that I could get a message from him to any of the officers there. In fact some of the Northern men there are disaffected and about 100 of them are disarmed and more or less semi-prisoners. I am in touch with them. If you could forward me [a] note I could get it through to Woods; he is in the Curragh.”[13]

To avert the prospects of a potential mutiny, those among the Belfast contingent in the Curragh who decided to join the Free State Army were dispersed among various barracks – some were kept in the Curragh, while other sizeable groups were soon stationed in Dundalk and at Wellington Barracks in Dublin.[14]

McCorley himself commanded a unit that was sent to break up a riot by Republican prisoners in Mountjoy Gaol in Dublin.[15]

Later, the northern IRA veterans were re-grouped into a single unit in the Free State Army, along with non-IRA recruits from Belfast, and sent to Kerry. Roger McCorley recalled:

“I was sent south to Kerry with a unit which consisted of half Belfast men and half 2nd and 3rd Northern men. We went to Kenmare until March. Then I was fed up. I came back to the Curragh. I wanted to get out of the army or get out of Kerry. The unit then was formed into the 17th Bn., sent to the workhouse in Tralee. Joe Murray, a Belfast man, was in charge of it then.”[16]

There was substantial recruitment for the Free State Army among Belfast nationalists in general, many of whom were ex-servicemen of the British Army. The Army Census conducted in November 1922 shows that a total of 680 men from Belfast had enlisted – but 501 or 74% of them had no documented involvement with the Belfast IRA.[17]

Nearly 700 Belfast men had already joined the National Army by November 1922 and ten had been killed in action, but most of these had not previously served in the IRA.

Ten natives or former residents of Belfast who had joined the Free State Army were killed during the initial months of the Civil War, but all of those deaths occurred before the breakup of the Belfast contingent in the Curragh and none of the men killed had any prior connection with the IRA in Belfast.[18]

However, four former members of the Belfast Brigade were killed during the Civil War.

Dublin native Joseph Foster had worked as a carpenter in the shipyards until the expulsions at the start of the Pogrom in July 1920. A member of B Company, 1st Battalion of the Belfast Brigade, since before the Truce of July 1921, he joined the Free State Army in Dublin in July 1922 and was stationed in Clonmel, Co. Tipperary. On 18th January 1923, he was killed in an ambush at Ninemilehouse, near Clonmel.[19]

James Montgomery from the ‘Bone had been a member of A Company, 2nd Battalion and had been arrested in connection with the killing of District Inspector Oswald Swanzy in Lisburn in August 1920. He enlisted in the Free State Army in the Curragh in August 1922 but was killed accidentally on 23rd April 1923 while searching for anti-Treaty IRA near Monasterevan, Co. Kildare – a fellow-soldier discharged his rifle by mistake.[20]

A member of the pro-Executive Brigade was also killed during the Civil War, but it is unclear whether the killing was due to the Civil War. On 30th December 1922, Hugh O’Connell from Cairns St in the Lower Falls went to Dundalk for the day with his wife and baby. He had been in the town the previous summer, presumably with the pro-Executive Brigade column; he told his wife he had “to meet with some of the boys that were Irregulars” and arranged to meet her later; his body was found with a fatal gunshot wound later that evening.[21]

None of these were the first member of the Belfast IRA to be killed in the Civil War – that was Joe McKelvey, O/C of the 3rd Northern before the split, who was executed by the Free State government in Mountjoy Jail on 8th December 1922, in reprisal for the IRA assassination of Sean Hales TD.

Quantifying the split

So, more Belfast men died defending the Treaty than opposing it in 1922-23. But what does this tell us about the political sympathies of Belfast Republicans?

Ordinarily, measuring the extent of the split in the IRA over the Treaty would be relatively straightforward. Brigade Committees were set up across the country to assist in the process of verifying applications for military service pensions; one of the ways in which they did so was by compiling nominal rolls of IRA members, down to company level, for each of two “critical dates” – 11th July 1921, marking the start of the Truce, and 1st July 1922, at the start of the Civil War. Anyone listed for the second date was assumed to be a member of the Executive Forces.

But for Belfast, the process of measurement is enormously complicated by the actions of its Brigade Committee, who wove a web of evasions, deceptions and half-truths, possibly with the intention of obscuring the degree to which the IRA in the city had been affected by the split.

Quantifying the split in the Belfast IRA is complicated by the fact that it did not strictly follow the lines southern pro vs anti-Treaty divides along which nominal rolls were later assembled.

The Committee initially set up was composed of a mixture of pre-Truce officers who had not gone to the Curragh and pro-Executive officers, with the pro-Executive members in a minority.[22] There was a subsequent proposal to add a number of “Corvin nominees” to ensure balance between the two sides, although it is unclear if this was acted on.[23]

A few examples will illustrate the fog of confusion which they created:

- C Company of the 1st Battalion – described by Hugh Corvin as being “antagonistic” (to the pro-Executive Brigade) – was entirely written out of the nominal roll for the second date; instead, it was described as having merged with E Company of the same Battalion to form a new combined C&E Company – but only 6 of its 113 pre-Truce members were listed as being pro-Executive Brigade members.[24]

- The 2nd Battalion was described as having no Battalion Staff at all on 1st July 1922 – a mere five days after its O/C Séamus Timoney wrote the second of his angry reports to his Brigade O/C and a week before the arrest of its Quartermaster, Henry Crofton. Its B Company was described as being “only skeleton” although a list of its officers was included and there were enough active members on either side of the split to engage in the shooting incident over arms dumps that erupted in Ballymacarrett in late June.[25]

- A 3rd and 4th Battalion were reported to have been formed after the Truce but then dissolved before 1st July 1922, so no nominal rolls were provided for them. However, when the absence of nominal rolls threatened to derail a particular pension applicant’s claim, it suddenly became possible to provide a nominal roll listing 93 men of A Company of the 4th Battalion, of which he had been an officer.[26]

Having navigated the Brigade Committee’s smoke-and-mirrors illusion, and supplementing their lists from other sources, it is possible to say the following.[27]

Prior to the Truce, there were 1,220 male Republican combatants in Belfast – 1,075 IRA and 145 Fianna; a minimum of 268 more joined after the Truce, giving a combined total of 1,488.[28]

By the summer of 1922, 32 of them had been killed in the north and at least 52 were in prison, having been either arrested or interned.

The latter figure is without doubt an underestimate, as not all arrests were reported in detail by the newspapers; in addition, many men named in newspapers’ court reports as facing what appear to be IRA-related charges do not appear on any IRA membership lists. Many more IRA members would go on to be interned in the autumn and winter of 1922. For the present purposes, neither those killed nor those in prison are counted as being part of the split.[29]

While a majority remained loyal to GHQ in the initial split of March-April 1922, this did not mean that the majority also served in the Free State Army.

While a majority remained loyal to GHQ in the initial split of March-April 1922, this did not mean that the majority also served in the Free State Army – more men remained in the anti-Treaty or ‘Executive’ Belfast Brigade.

In total, 179 or 12% of Belfast Brigade members eventually joined the Free State Army. This includes 35 who had been listed as pro-Executive Brigade members on 1st July 1922; the fact that they later joined the pro-Treaty army in the Civil War does not necessarily imply a change of allegiance, it simply reflects the fact that everyone included in the nominal rolls at that date was counted as a pro-Executive member.

Far more men remained members of the pro-Executive Brigade in Belfast than joined the Free State Army – 480 or 32% of the total. Interestingly, this number was almost equally divided between those who had pre-Truce records and so-called “Trucileers” who joined afterwards, as the violence in Belfast continued: 237 had been in the IRA or Fianna prior to the Truce, 243 had not.

Equally significantly, all but 25 of the 268 who joined the IRA after the Truce remained with the pro-Executive or anti-Treaty Brigade. These newer members had, according to one (admittedly bitter) long-standing IRA officer, more primitive motivations for joining: “I would say that about two-thirds of these recruits – possibly three-fourths – joined the I.R.A. for sectarian reasons only, to fight defensively or offensively against the Orange gangs. Few of them had any concept of Irish-Ireland principles.”[30]

The largest single group were those who dropped out of the Belfast IRA rather than take a side in the Civil War.

The Fianna all but vanished in 1922. Of its 145 known members, 7 were killed, 14 joined the Free State Army and 2 “graduated” to the pro-Executive Brigade, but the other 122 had no further involvement with any organisation.

The same can be said about what is by far the largest group in the study – 617 or 57% of the 1,075 men who were in the IRA before the Truce had dropped out of activity by the summer of 1922, joining neither the Free State Army nor the pro-Executive Brigade. This number includes men who initially went to the Curragh but, once it became clear that there would be no second northern offensive, opted to return home rather than joining the Free State Army.[31]

Combining this group with the Fianna who also dropped out, 61% of the men and boys who had been involved in the War of Independence in Belfast prior to the Truce were no longer active by the time of the Civil War.

Cumann na mBan

Before the IRA held its Army Convention at the end of March 1922, Cumann na mBan held its own convention in Dublin on 5th February. Mary MacSwiney proposed a motion rejecting the Treaty and re-affirming the organisation’s allegiance to the Republic – an anonymous “Belfast delegate” supporting the motion said: “Mrs Wyse-Power has said she has seen the army of occupation leaving Ireland. It is not. It is being drafted into the Six Counties. We want a Republic. Nothing else.”[32]

The motion was carried, with 419 delegates voting in favour and only 63 against:[33]

“The counties were taken alphabetically beginning with Antrim and our delegate’s name was called first. Her ‘Ní tóil’ was flung into the assembly in a voice that could have been heard at the Cave Hill. ‘Up Belfast!’ said my neighbour on the gallery. The other Belfast and County Antrim delegates were as emphatic.”[34]

While not as numerically decisive as the Convention vote, Belfast Cumann na mBan split on similar lines with a clear majority that we know of aligning themselves with the pro-Executive Brigade in Belfast. In the absence of nominal rolls of Cumann na mBan members – none were submitted for Belfast to the Military Service Pensions (MSP) Board – this assessment is based on the twenty-seven Belfast women for whom files have so far been released from the Military Service Pensions Collection (MSPC).

The majority of a sample of 27 Belfast Cumman na mBan women whose military pensions have been released, sided against the Treaty

Of those, seven were no longer active in Belfast at the time of the Treaty split, mainly due to moving elsewhere, although one Republican woman took an explicitly neutral stance on the Treaty – Mary Hannan, whose vows as a nun precluded her from officially joining Cumann na mBan.[35]

Six of the women remained active until “the big round-up” in May 1922, after which they had no further involvement with Cumann na mBan, so it can be inferred that they were associated with the pro-GHQ Brigade in Belfast.[36]

Similarly, Winifred Carney was arrested in July 1922; following her release three weeks later, her remaining involvement was with the Republican Dependents Fund rather than with Cumann na mBan.[37]

However, the remaining thirteen women claimed for and were awarded service with Cumann na mBan up to and including various points in 1923 and for some of those, it is clear from their MSPC files that they were actively involved in assisting the pro-Executive Brigade in Belfast and beyond.[38]

Easter Rising veteran Nell Corr stated that she had “Helped in despatch of arms to Dundalk on two occasions.”[39] Nellie O’Boyle was also very active in relation to the Louth column:

A: …I also carried fire arms to Dundalk on several occasions when they wanted stuff.

Q: How many trips did you make to Dundalk?

A: Four.

Q: Who did you take them to?

A: First into Anne Street Barracks. There was a flying column sent from Belfast to Dundalk and they did not get through as the bridges were blown up.”[40]

Katherine McNearney’s opposition to the Treaty was perhaps the most strident among the women of Belfast Cumann na mBan. When applying for a pension in the 1930s, she came to the question on the form that asked whether she had applied previously under the older 1924 Military Service Pensions Act – her response was forthright: “On principle as a Republican I would not apply for pension or assistance to the then styled government whose interests did not serve my country or the people.”[41]

Summary and conclusions

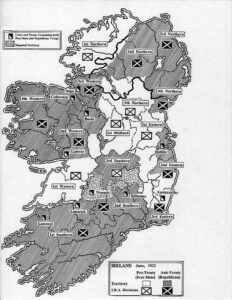

Maps showing the Civil War split of the IRA into pro- and anti-Treaty Divisions often assign the 3rd Northern to the anti-Treaty side, perhaps on account of the prominent role played by its former O/C, Joe McKelvey. The reality was more nuanced.

By the spring of 1922, there were two 3rd Northern Divisions in Belfast, both opposed to the Treaty and both seeking to overturn its provisions in relation to partition. Where they differed was in relation to how to achieve that objective.

The strategy of the pro-Executive Brigade in Belfast, like that of their counterparts in the south, was rooted in Republican ideology: they sought to continue the fight to achieve a 32-county Irish Republic – the one that had been proclaimed at Easter 1916 and again in January 1919 had never been established in tangible terms in Belfast.

The approach of the pro-GHQ Brigade was more pragmatic. Like their pro-Executive counterparts, they looked to the south for moral and material support and after the IRA Convention of March 1922, they viewed the pro-Treaty GHQ in Dublin as the more promising source of such support. Their loyalty to GHQ reflected a logistical preference, not a shared ideology.

By the spring of 1922, there were two antagonistic 3rd Northern Divisions in Belfast, both opposed to the Treaty, but one loyal to the pro-Treaty IRA leadership and the other cleaving to the anti-Treaty Executive.

The pro-Executive Brigade was the more fractious of the two Brigades in Belfast. Apart from the operation to disarm police in Millfield at the end of May, its most notable actions were episodes in which it either veered close to or actually became involved in shooting incidents with other units of the IRA, in Belfast and Louth. However, its impact on the Unionist government was negligible – that government’s fear of it was based more on what the IRA as a whole stood for rather than anything the pro-Executive faction actually did.

The make-up of the pro-Executive Brigade is striking in two respects: first, the almost-even divide in its ranks between pre- and post-Truce recruits, and second, the fact that an overwhelmingly large majority – 91% – of the latter “went Executive.” The cruder motivations attributed to these Trucileers may explain the abortive attempt to attack the 12th July parade. If that attack had proceeded as planned, the likely repercussions for nationalists, in the form of loyalist retaliation, would have been catastrophic.

For its part, the pro-GHQ Brigade staked everything on the May Northern Offensive, a plan that was both grandiose and delusional and which had been concocted in Dublin primarily to suit the interests of its Dublin architects. Deprived of support from outside Belfast and battered within Belfast by the Unionist response to the offensive, in terms of both the Special Powers Act and the Special Constabulary, the RUC intelligence success in early July proved the final tipping point that drove an already weakening pro-GHQ Brigade to break and run for the Curragh.

While more Belfast men fought on the pro-Treaty than anti-Treaty side in the Civil War, the idea that the majority of the Belfast IRA did so is in need of revision.

There they could engage in face-saving preparations for a second offensive that never came, while they slowly discovered that the post-Collins Provisional Government was exclusively focussed on events south of the border.

A misconception exists (for which this author is partially culpable) that the majority of the Belfast IRA went to the Curragh and subsequently joined the Free State army.

This may be due to the fact that for a long time, the majority of first-hand Republican accounts available for Belfast in this period were those provided to both the Bureau of Military History and to Ernie O’Malley by former pro-GHQ Brigade officers, many of whom did in fact have subsequent military careers. But they were not representative of the wider Belfast Brigade. This selection bias was reinforced by the fact that collections such as the Mulcahy Papers in UCD Archive naturally only contain documents relating to the pro-GHQ Brigade.

The narrative is further complicated by the fact that a lot of men from Belfast and elsewhere in the north did actually join the Free State Army. As noted above, the Army Census conducted in November 1922 shows that a total of 680 men from Belfast had done so by that point, but most of them had had no involvement with the IRA. This sizeable non-IRA contingent from Belfast probably coloured perceptions and may have been assumed to have been Belfast IRA men who had gone to the Curragh.[42]

However, with the release in recent years of MSPC files, including those of pro-Executive Brigade members and the nominal rolls, as well as the results of the Army Census, there is now enough new evidence to tell a more accurate story.

It is true that far more Belfast Republicans were involved on the pro-Treaty than anti-Treaty side as combatants in the Civil War.

Several members of the pro-Executive Brigade were involved in the Civil War at an individual level – Pat Thornbury and Joseph Billings took part in the fighting around O’Connell Street in Dublin in early July, while Michael Carolan became the anti-Treaty IRA’s Director of Intelligence.[43]

But given the involvement of both IRA and Cumann na mBan members, the mobilisation of the Louth column in July 1922, which attempted to make its way south to aid their beleaguered comrades in Dublin, was clearly the most significant contribution en masse of the pro-Executive Brigade after the start of the Civil War.

Yet this column only involved around thirty men, roughly a sixth of the number that would ultimately join the Free State Army.

Nevertheless, within Belfast, more than two-and-a-half times as many remained involved with the pro-Executive Brigade – at least until internment intervened later – than transferred into the Free State Army: 480 as against 179.

But without a doubt, the largest group among IRA and Fianna members in Belfast was those who simply dropped out in 1922 – 739 of those active before the Truce had no involvement after the Northern Offensive. They may well, as Woods claimed, have been loyal to GHQ, but none of them were loyal enough to join GHQ’s new army.

Nor was it the case that they had no appetite for what proved to be a debilitating split. It simply marked a grudging acceptance on their part that the War of Independence on which they had originally embarked had, by the summer of 1922, finally been defeated in the north.

The leadership of the pro-GHQ Brigade of the Belfast IRA would take several more months to recognise that fact. Arguably, the pro-Executive Brigade never did.

References

[1] Statement to Advisory Committee, 19th April 1940 in Henry Crofton, Pensions & Awards files, Military Service Pensions Collection (MSPC), Military Archives (MA)A, MSP34REF00106.

[2] Henry Crofton to Secretary, Minister for Defence, November 1927, ibid.

[3] Nominal Roll of “Specialists”, 2nd Battalion, 1st Brigade, 3rd (Northern) Division; List of Commissioned Officers in Battn. working; List of Commissioned Officers in Battn. not working; all in Internment of Henry Crofton, Public Record Office of Northern Ireland (PRONI), HA/5/961A.

[4] O/C 3rd Northern Division to Chief of Staff, 20th July 1922, Mulcahy papers, UCD Archives Department (UCDAD), P7/B/77.

[5] MSP Assessor interview with Patrick Thornbury & Hugh Corvin, in Michael Carolan, Pensions & Awards files, MSPC, MA, MSP34REF20261. Thornbury was mistaken in one respect: after his release from internment, Crofton joined the Gardaí – it was McPeake who joined the Free State Army, serving until the 1930s.

[6] O/C 3rd Northern Division to Chief of Staff, 27th July 1922, Mulcahy papers, UCDAD, P7/B/77.

[7] File on Pension Claims by Northern IRA Personnel, Ernest Blythe papers, UCDAD, P24/554.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Commander-in-Chief to O/C 3rd Northern Division, 20th October 1922, Mulcahy papers, UCDAD, P7/B/287.

[10] Joseph Murray statement, Bureau of Military History (BMH), MA, WS0412.

[11] Roger McCorley interview with Ernie O’Malley in Síobhra Aiken, Fearghal Mac Bhloscaidh, Liam Ó Duibhir & Diarmuid Ó Tuama (eds) The Men Will Talk To Me: Ernie O’Malley’s Interviews with the Northern Divisions (Kildare, Merrion Press, 2018), p103.

[12] Memo from Secretary, Ministry of Home Affairs to Cabinet Secretary, 5th February 1923, File on reports of recruits leaving Northern Ireland to join Irish Free State Army, PRONI, HA/32/168.

[13] Assistant Chief of Staff to Chief of Staff, 3rd September 1922, Moss Twomey papers, UCDAD, P69/40.

[14] See https://www.militaryarchives.ie/collections/online-collections/irish-army-census-collection-12-november-1922-13-november-1922

[15] John Dorney, The Civil War in Dublin, The Fight for the Irish Capital (Kildare, Merrion Press, 2017), p200. After the Civil War, McCorley became the Defence Forces’ first Provost Marshal or head of the military police.

[16] Roger McCorley interview with Ernie O’Malley in Aiken et al, The Men Will Talk To Me, p104.

[17] See https://www.militaryarchives.ie/collections/online-collections/irish-army-census-collection-12-november-1922-13-november-1922 The figure of 680 includes men who were not included in the Army Census but whose enlistment is confirmed by other documents e.g. their MSPC files.

[18] William Carson, Pensions & Awards files, MSPC, MA, 2D242 (killed in Tralee, Co. Kerry, 3rd August 1922); Edward McEvoy, Pensions & Awards files, MSPC, MA, 2D93 (killed at Ferrycarrig, Co. Wexford, 9th August 1922); William Purdy, Pensions & Awards files, MSPC, MA, 2D40 (killed in Abbeyfeale, Co. Kerry, 11th August 1922); Cyril Lee, Pensions & Awards files, MSPC, MA, 2D378 (killed near Macroom, Co. Cork, 27th August 1922); Michael Magee, Pensions & Awards files, MSPC, MA, 2D244 (killed in Castleisland, Co. Kerry, 11th September 1922); Bernard Gray, Pensions & Awards files, MSPC, MA, 2D289 (killed at Coachford, Co. Cork, 18th September 1922); Charles Flynn, Pensions & Awards files, MSPC, MA, 2D326 (killed in Limerick, 19th September 1922); Daniel Hannan, Pensions & Awards files, MSPC, MA, 2D68 & 2D425 (killed at Farranfore, Co. Kerry, 27th September 1922); Charles Kearns, Pensions & Awards files, MSPC, MA, 2D298 (killed in Cork city, 9th October 1922); Bernard Conaty, Pensions & Awards files, MSPC, MA, 2D360 (killed near Carrickmacross, Co. Monaghan on 21st November 1922). Eight other Free State Army soldiers from Belfast with no links to the IRA were either killed in action, killed accidentally or died of non-combat illnesses during 1923.

[19] Nominal Roll, 3rd Northern Division, 1st Brigade, 1st Battalion, MSPC, MA, MSPC/RO/403; https://census.militaryarchives.ie/pdf/Clonmel_2_Southern_Division_Page_44.pdf ; Joseph Foster, Pensions & Awards files, MSPC, MA, 3D261 & RGU13632.

[20] James Montgomery, Pensions & Awards files, MSPC, MA, 3D51.

[21] Drogheda Argus & Leinster Journal, 6th January 1923.

[22] P. Fox (Secretary) to MSP Board, 30th April 1936, in Nominal Roll, 3rd Northern Division, 1st Brigade GHQ, MSPC, MA, MSPC/RO/402.

[23] “Suggested Bde. Cttee. per J. Keenan”, 13th September 1939, in ibid. Hugh Corvin had succeeded Thornbury as O/C of the pro-Executive 3rd Northern after the latter was captured in October 1922.

[24] Nominal Roll, 3rd Northern Division, 1st Brigade, 1st Battalion, MSPC, MA, MSPC/RO/403.

[25] Nominal Roll, 3rd Northern Division, 1st Brigade, 2nd Battalion, MSPC, MA, MSPC/RO/404.

[26] Nominal Roll, 3rd Northern Division, 1st Brigade, 4th Battalion, MSPC, MA, MSPC/RO/406.

[27] In November 1926, a group of nine former 3rd Northern Division officers reviewed a list of applicants under the 1924 Military Service Pensions Act to determine who had or hadn’t served in the pre-Truce IRA; of those who they said had, thirty-two were not in the nominal rolls – these are included in the total. The fact that they applied for pensions under the 1924 Act does not automatically mean they were members of the Free State Army, although that was one of the qualifying conditions of that Act – their applications may well have been rejected and until their files are released, we cannot say for sure whether they did join it. In addition, Belfast-based recipients of 1917-21 campaign medals who are not mentioned in any other list are assumed to have had pre-Truce service. Special Investigation of Six County Cases, MSPC, MA, SPG10 A2; medal awards can be searched by county at: http://mspcsearch.militaryarchives.ie/search.aspx

[28] The absence of nominal rolls for all of the 3rd Battalion and nearly all of the 4th Battalion means the figure of 268 is hugely under-stated.

[29] For those killed, see https://www.theirishstory.com/2020/10/27/the-dead-of-the-belfast-pogrom-counting-the-cost-of-the-revolutionary-period-1920-22/#.Yge2LN_P2Ul For a partial list of those arrested, see Special Investigation of Six County Cases, MSPC, MA, SPG10 A1. Some, but not all, of those arrested prior to 1st July 1922 were included in the nominal rolls for that date, again illustrating the flaws in the lists compiled by the Brigade Committee – here, they are counted as being in prison rather than members of the pro-Executive Brigade.

[30] Séamus McKenna statement, BMH, MA, WS1016.

[31] A final tiny group of six men who had post-Truce involvement in the IRA also dropped out, joining neither the Free State Army nor the pro-Executive Brigade.

[32] Minutes of the Cumann na mBan Special Convention, Material relating to Constance de Markievicz, Padraic Pearse and others, NLI, Ms 49,851/10. My thanks to Mary McAuliffe for highlighting that this document can be viewed on the NLI website.

[33] Margaret Ward, Unmanageable Revolutionaries (Dublin, Arlen House, 2021), p288.

[34] Elizabeth Corr, “A Belfast Visitor’s Impression”, quoted in Margaret Ward, Gendered Memories and Belfast Cumann na mBan, 1917-1922 in Linda Connolly (ed.), Women and the Irish Revolution (Newbridge, Irish Academic Press, 2020), p65.

[35] Teresa McDevitt, Pensions & Awards files, MSPC, MA, MSP34REF11023; Theresa McKenna née Shevlin, Pensions & Awards files, MSPC, MA, MSP34REF21100; Emily Velentine, Pensions & Awards files, MSPC, MA, MSP34REF56551; Brigid McGeown, Pensions & Awards files, MSPC, MA, MSP34REF63325; Mary Russell, Pensions & Awards files, MSPC, MA, MSP34REF24769; Alice Kerr, Pensions & Awards files, MSPC, MA, MSP34REF14525; Mary Hannan, Pensions & Awards files, MSPC, MA, 34SP10713.

[36] Amy Murphy, Pensions & Awards files, MSPC, MA, MSP34REF16261; Elizabeth Delaney, Pensions & Awards files, MSPC, MA, MSP34REF26212; Elizabeth McClean, Pensions & Awards files, MSPC, MA, MSP34REF27554; Mary McClean, Pensions & Awards files, MSPC, MA, MSP34REF27555; Agnes O’Boyle, Pensions & Awards files, MSPC, MA, MSP34REF57567; Alice Flynn, Pensions & Awards files, MSPC, MA, MSP34REF57942.

[37] Winifred Carney, Pensions & Awards files, MSPC, MA, MSP34REF56077.

[38] Rose Black, Pensions & Awards files, MSPC, MA, MSP34REF22470; Mary Hackett, Pensions & Awards files, MSPC, MA, MSP34REF23258; Kathleen McCorry, Pensions & Awards files, MSPC, MA, MSP34REF24001; Nora McCarthy née Quinn, Pensions & Awards files, MSPC, MA, MSP34REF24338; Maggie Fitzpatrick, Pensions & Awards files, MSPC, MA, MSP34REF26214; Alice McKeever, Pensions & Awards files, MSPC, MA, MSP34REF51358; Annie McKeever, Pensions & Awards files, MSPC, MA, MSP34REF51359; Frances Cooney, Pensions & Awards files, MSPC, MA, MSP34REF57444; Bridie O’Farrell, Pensions & Awards files, MSPC, MA, MSP34REF8038; Elizabeth Corr, Pensions & Awards files, MSPC, MA, MSP34REF10854.

[39] Nell Corr, Pensions & Awards files, MSPC, MA, MSP34REF10855.

[40] Nellie Neeson née O’Boyle, Pensions & Awards files, MSPC, MA, MSP34REF11037.

[41] Katherine McNearney, Pensions & Awards files, MSPC, MA, MSP34REF51183.

[42] See https://www.militaryarchives.ie/collections/online-collections/irish-army-census-collection-12-november-1922-13-november-1922 The figure of 680 includes men who were not included in the Army Census but whose enlistment is confirmed by other documents e.g. their MSPC files.

[43] Patrick Thornbury, Pensions & Awards files, MSPC, MA, MSP34REF07497; Joseph Billings, Pensions & Awards files, MSPC, MA, MSP34REF01089; Michael Carolan, Pensions & Awards files, MSPC, MA, MSP34REF20261.