Book Review: Free Statism & The Good Old IRA

By Danny Morrison,

By Danny Morrison,

Published by: Greenisland Press, 2022

Reviewer: Brian Hanley

ISBN 9783949573002

€17. £15.

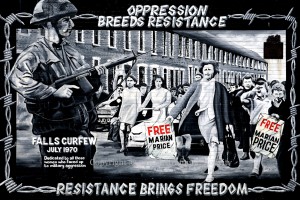

In the mid-1980s one of the major fault lines in southern Irish society concerned attitudes to the war taking place north of the border. After a period in the early 1970s, when there was widespread sympathy for northern nationalists, many if not most of the south’s population had grown disillusioned, estranged and fearful of any engagement with the issue at all.

An exception had been the period during the hunger strikes of 1980-81, but that too seemed to have passed by 1985. The republican movement was a factor in political life, though very much a minority one. Supporters of Sinn Féin were banned from RTE under Section 31 of the Broadcasting Act and while they held a handful of local council seats, had no representation in Leinster House.

Indeed it was not until 1986 that Sinn Féin dropped its long-standing abstentionist policy in the Republic; but in the 1987 general election the party polled just 1.8% of the vote. Sinn Féin’s vote dropped to just 1.2% in 1989 and three years later was only marginally higher at 1.6%.

Nevertheless the republican movement was visible, not least because the IRA’s armed campaign was never far from the headlines or day to day discourse. They were often the only people supporting, or at least defending this struggle; most mainstream politicians and commentators loudly and repeatedly denounced the IRA. Very often they did so by comparing them unfavourably to the IRA of the War of Independence, what was often referred to as the ‘old IRA’ (though that term was in use as early as 1922).

Hence in August 1984, when Fine Gael Minister for Justice Michael Noonan addressed the annual Béal na Bláth commemoration he not only asserted that ‘our generation of the Irish owes more to Collins than to any other hero’ but also demanded that the modern IRA ‘emulate’ Collins by ending its armed campaign.

A Troubled Context

The immediate republican response to this was an editorial in An Phoblacht/Republican News in which Mick Timothy dismissed the idea that there was any difference between the ‘old’ and modern IRAs. Timothy’s editorial formed the introduction to The Good Old IRA published by the Sinn Féin Publicity Department during 1985.

While often assumed to have been written solely by Danny Morrison, then Sinn Féin’s Director of Publicity, it was actually a collaborative effort with much of the research carried out by Brian McDonald, Hugo Reavey and Fintan McPhilips.

The original ‘Good Old IRA’ pamphlet was published in 1985 in response to criticisms from south of the border of the Provisional IRA campaign.

The main body of the pamphlet consisted of a listing of IRA actions between 1919-21. There were details of the shooting of informers, of dozens of cases where civilians (including women and children) were killed in cross-fire, and many killings of unarmed police and military. The Good Old IRA did not claim to be

‘a definitive list of IRA operations in the 1919–21 period. Indeed the majority of attacks on RIC, Black and Tans and regular soldiers are not included. Nor is the death of every civilian recorded. This list is morbid enough and is intended to illustrate a number of important points to confront those hypocritical revisionists who winsomely refer to the ‘Old IRA’ whilst deriding their more effective and, arguably, less bloody successors.’

The authors hoped that ‘even if these operations are shocking revelations to those who have a romantic notion of the past then the risk of their disillusionment is worth the price of finally exposing the hypocrisy of those in the establishment who rest self-righteously on the rewards of those who in yesteryear’s freedom struggle made the supreme sacrifice.’

Confronting criticism that the Provisional IRA campaign was largely being waged against Irish people, they argued that ‘the reality is that any colonial war native agents and informers, be they of the same or opposite race, religion, colour or creed, were struck down for being agents and informers. The same is true today.’

And far from claiming that the War of Independence possessed a democratic mandate, Mick Timothy’s introduction asserted that in fact ‘nobody was asked to vote for war’ in December 1918 and claimed that after those elections ‘there was still a year before the first RIC men were to be shot down.’

But did not the elections of May 1921 show a majority supported Sinn Féin? Timothy asserted that this was ‘not so … You forget, do you not, that just like the SDLP in Fermanagh/South Tyrone 60 years later, the other parties were ‘advised’ to stand aside on this occasion. In 124 constituencies, the Sinn Féin candidates were returned entirely unopposed. Not so much elected as selected, you understand.’ It was hard-hitting stuff and certainly an antidote to the rose-tinted view which many had of the ‘old’ IRA.

Ironically some of the points raised in the ‘Good Old IRA’ echoed revisionist criticisms of Irish republican history.

The irony was though that many of the pamphlets assertions would have been roundly denounced by republicans if written by someone critical of the IRA. Indeed some revisionists would have agreed with what Timothy had to say about the 1918 election and nodded their heads at the numerous cases outlined where the ‘old’ IRA had killed for seemingly dubious reasons.

After all, as Gerry Adams once noted, the most famous revisionist of them all, Conor Cruise O’Brien, agreed that there was no ‘good old IRA’; indeed as far as O’Brien was concerned they ‘were just as bad in 1916 as they are today. Neither the methods nor the objectives have changed. Connolly or Pearse, if alive today, would surely be in the republican movement.’

Indeed the pamphlet was actually influential among those historians who sought to reconstruct the brutality of the republican campaign of 1919-21. Because it focused on violence The Good Old IRA ignored evidence of the mass support for independence.

Mass struggle and armed struggle

The underground Dáil administration, the general strikes, boycotts and civil resistance that were so crucial to republicans did not feature at all. It also ignored the 1920 local elections, in which Sinn Féin (along with Labour) secured large majorities over much of Ireland and which took place while an armed campaign was escalating.

There was no sense either of the unique global moment of which the struggle for independence was part. It was all of those things that meant the Ireland of the 1980s was very different to that of 1920.

This was not fundamentally a question of morality but of politics. The Good Old IRA depicted the IRA’s activities between 1919-21 in the worst possible light, in order to make the modern IRA’s war palatable by comparison. Some of the stories it reproduced actually originated as British atrocity propaganda and others remain contentious.

When published it certainly possessed a raw polemical power, though its novelty has been lessened by time. Nevertheless it is fair to say that the idea of a more ‘pure’ ‘old’ IRA is still a fairly common one. Indeed Micheál Martin has contrasted ‘the heroes who fought for Irish freedom in 1916’ with the ‘dirty and nasty’ campaign of the Provisional IRA.

Now the pamphlet has been republished as a book, Free Statism and the Good Old IRA with several extra chapters by Danny Morrison. The historical section survives largely intact, with new additions on the role of the Catholic Church, the IRA in Britain and the ‘disappearing’ of people by the IRA under the leadership of Richard Mulcahy. Some of this material draws on the work of historians such as Pádraig Óg Ó Ruaric, Andy Bielenberg and John Borgonovo, though they are not acknowledged.

However the book has a new focus, what Morrision calls ‘Free Statism … promotion of the idea that Ireland consists of twenty-six counties and that the nation stops at the Border.’

‘Free Statism’

He is angry about this and his prose reflects the very real sense of betrayal felt by generations of northern nationalists. Elements in the southern media and political establishment certainly do use the conflict to score partisan political points off Sinn Féin.

And it is condescending to young voters to assume they only support Sinn Féin because they can’t remember the Troubles. There needs to be a reckoning not only about collusion, but also the truth behind British involvement in bombings in the Dublin and elsewhere. I get annoyed too when ‘Ireland’ is used as short hand for the 26 counties.

But like it’s earlier version, Free Statism and Good Old IRA is a polemic, with all the strengths and weaknesses of that genre. Southern hypocrisy is skewered repeatedly, but there is little awareness displayed of either historical or political context. There are errors; it was WT Cosgrave, not Richard Mulcahy, who talked of ‘exterminating’ 10,000 republicans; the tricolour at Leinster House was lowered to half-mast after Kieran Doherty’s death in 1981 (this features in the relevant episode of RTE’s Reeling in the Years).

Like it’s earlier version, Free Statism and Good Old IRA is a polemic, with all the strengths and weaknesses of that genre

More importantly there are numerous omissions. In a book which is partly aimed at stimulating debate about the future of a united Ireland, there needed to be some sense of where the divisions between us (not just unionist and nationalist, but north and south) come from.

So Morrison denounces the Home Rule party for betraying nationalists by accepting (temporary) partition, but doesn’t explain how the same party could not only hold West Belfast in December 1918, but win five of its just six seats in nationalist Ulster in the midst of Sinn Féin’s landslide.

‘The North let us down’

Fifty years later the Belfast-born Seán MacEntee lamented bitterly that in that election ‘the majority of the Nationalists had let us down. West Belfast, South Down, North-East Tyrone and South Armagh had cut themselves off from Republican Ireland. The nationalists of West Belfast had chosen ‘Wee Joe’ Devlin instead of Mr. de Valera, a choice that particularly had disastrous consequences for the people and for Ireland.’

While a long-serving Fianna Fáil minister might well be accused of being self-serving here, such views were not rare among republicans. In October 1934, An Phoblacht, no less, carried an article by a ‘Northern Republican’ who asked rhetorically ‘Who let the North down?’ and concluded that ‘The North let itself down.’ [See here An Phoblacht 1925-1935 27-10-1934]

Asserting that ‘Self pity’ was the ‘prelude to senility’ they alleged that ‘the nationalist people of the north are well advanced in their dotage.’ The article suggested that ‘up to the early part of 1920 the number of active Volunteers in the North-East was infinitesimal. It was only the sectarian riots in Belfast and Derry which drove large numbers into the ranks of the Republican Army. It was a gesture of self defence and nothing more …’

Worse, it then claimed, ‘when the “Treaty” came, nowhere was it supported with more scurrility and venom than in the Six Counties … To crown all, the number which joined the “Free State” army from the North-East was far in excess (in proportion to the relative geographical dimensions) of those who joined in the rest of Ireland.’

Republicans of the late 1920s blamed northern nationalists for their support of Home Rule nationalists and Free State forces during the Civil War

Other republicans made similar claims. Todd Andrews would write that the Anti-Treaty IRA’s resistance in Kerry was ‘finally crushed by troops drawn specially from the ‘tough’ men of the Dublin and Northern units.’

Kieran Glennon in his study of the Belfast pogroms has noted that the ‘difficulty for modern Republicans in trying to don the mantle of the original Belfast Brigade is that to do so, they must ignore the fact that the overwhelming majority of the men in whose footsteps they would claim to walk-in particular, the most influential officers and leaders-subsequently joined the Free State army and fought against Republicans in the Civil War.’ New research by Glennon himself is complicating this picture further but the significant role of northern IRA men in the Free State forces is not addressed in the book at all.

Prior to the Civil War thousands of nationalists fled south seeking refuge. They initially received a positive welcome. But there were discordant voices. One republican, Laurence Nugent, complained bitterly about how demanding the refugees allegedly were, claiming that the Belfast women ‘insisted on having milk hot from the cow morning and evening.’

Worse still, on the ‘formation of the Free State Army the men of the Belfast refugees joined up.’ In Nugent’s view “They bit the hand that fed them.” Another IRA man, Patrick Kelly described how a group of Belfast refugees who ‘objected to eating porridge for breakfast’ had raided shops in O’Connell St and that the IRA had to recover the stolen goods at gunpoint. What is significant about these claims is that both men were Anti-Treatyites, yet seem to have had little sympathy for northern nationalists.

This suggests that the divisions between northern and southern nationalists are not a new phenomenon. Morrison notes how the Unionist threat of rebellion, back by British Conservatives, helped destroy the prospect of Home Rule.

This is true, but contemporary republicans tended to see the emergence of the UVF as a positive development. I would be interested in Morrison’s views on why the leading Tyrone IRB man Patrick McCartan lent his car to the UVF to aid them in moving weapons after the Larne gunrunning (something publicly boasted about by Roger Casement).

It is also relevant to a discussion of partition to note that some republicans believed unionists had a claim to self-determination. Fr. Michael O’Flanagan, vice-president of Sinn Féin from 1917, suggested that while ‘geography has worked hard to make one nation out of Ireland, history has worked against it. The island of Ireland and the national unit of Ireland simply do not coincide … if the North East really wishes to stay out, by all means stay out until the majority of its people become convinced that they can best pursue liberty and happiness by coming in.’

While Morrison mentions in passing differences between northern and southern republicans, he misses how significant this was. This is important, because otherwise we won’t understand how southern republicans responded to partition the way they did.

‘Clean’ vs’ ‘dirty’ war

In comparing the IRA of different generations he would seem to be on firmer ground. After all, Micheál Martin is simply wrong to believe that the ‘old’ IRA never killed civilians or ‘disappeared’ alleged informers. It certainly did.

There are several examples in the book of the likes of Frank Aiken and Seán MacEoin’s involvement in political violence. But Morrison underestimates the impact of the modern IRA’s war. In the new edition Brian McDonald suggests that shortly before his death the legendary Cork IRA leader Tom Barry had expressed support for the Provisional IRA.

That may well be true. But in 1977 Barry had refused to add his name to an appeal for republican prisoners because of the IRA’s killings of northern businessmen. Barry told veteran activist Sighle Humphries that ‘the men who were carrying out the recent killings … could not be called IRA’ and that the ‘organisation was losing support from all quarters and they had only themselves to blame.’

Micheál Martin is simply wrong to believe that the ‘old’ IRA never killed civilians or ‘disappeared’ alleged informers

Barry could have changed his mind but what is clear is that the IRA’s actions impacted on potential supporters in ways that cannot be explained simply by ‘Free Statism.’

During the 1980s for example, Christy Moore was one of the few popular personalities to express support for the IRA. But in 1991 he explained that ‘I can no longer support the armed struggle. Its reached a point of futility. It doesn’t seem possible to carry out an armed struggle against the enemy. It’s an armed struggle in which too many little people are blown away.’ Moore described how incidents like ‘Enniskillen … thinking of how Tom Oliver was killed and how a kitchen porter was used in a proxy bombing ’ had forced him to re-evaluate his support.

If someone as well informed as Moore thought this way, then surely it is not surprising that large numbers of ordinary people felt the same? In the early 1990s the writer and activist Michael Farrell described how as ‘there have been more atrocities, completely indefensible actions and killings of civilians, a lot of people (in the south) have got very alienated by them and they have a sort of defence mechanism which is to turn off.’

Farrell accepted that ‘censorship contributes to that … but some aspects of the violence you could explain till the cows come home and it would still turn people off.’ Danny Morrison will rightly respond that violence was not the sole responsibility of the IRA. But in 1985 for example, when The Good Old IRA was originally published, 57 people died as a result of the conflict. 47 of them killed by republicans, five by loyalists and five by state forces.

Numbers of dead alone don’t tell you everything about a war, nor do they explain the myriad forms of oppression visited on those living in the six counties. They are however how most people in the ‘Free State’ would have related to the conflict, a seemingly never ending cycle of violence, in which republicans, most of the time, seemed to lead in terms of deaths inflicted.

Morrison himself has recalled canvassing in Strabane during the 1980s and meeting a voter who told him they were impressed by ‘the way you talk about the national question … but I cannot support those bombs.’ Hence he admits that there ‘was a ceiling on the support for Sinn Féin as a result of moral quandaries that people had over the armed struggle per se or aspects of the armed struggle.’ That ceiling was even lower south of the border.

While picking apart the day by day reality of the ‘old’ IRA will illustrate many dreadful things, no matter how deep you dig, you will not find the Tan War’s version of Bloody Friday, Claudy, Birmingham, La Mon, Enniskillen or Frizzell’s fish shop. Even allowing for the hypocrisy of those who claimed a moral superiority for the ‘old’ version, the reality of the modern IRA’s campaign in the 1980s was enough to alienate most people. And there were also marked differences between the two eras.

No matter how deep you dig, you will not find the Tan War’s version of Bloody Friday, Claudy, Birmingham, La Mon, Enniskillen or Frizzell’s fish shop

The ‘old’ IRA fought against an Empire which was at the height of its power. The modern IRA’s campaign took place in period in which the United Kingdom was in dramatic decline. The modern IRA waged recurring bombing campaigns against commercial and public property, destroying the north’s urban centres again and again. The ‘old’ IRA was never likely to bomb the centre of Dublin or Cork (in fact the British forces destruction of Irish towns was a major propaganda weapon for republicans.)

The ‘old’ IRA was a mass movement of over 100,000 volunteers, though very poorly armed. The modern IRA was much smaller but by the late 1980s at least, exceptionally well equipped. The Tan War IRA achieved more with less because it was part of a popular revolutionary movement and British rule in Ireland had no legitimacy for the majority. Partition ensured that the modern IRA represented a minority of a minority.

Some of the new additions to the text are less convincing then they seem to think they are. There is really no comparison between the very limited IRA campaign in England during 1920-21 and that of the 1970s. The Tan War republican leadership was very conscious of the need to enlist British popular sympathy and was quite successful in doing so.

And while it is true that the Catholic hierarchy often condemned republicans between 1916-21, they also condemned the British, usually in more forceful terms. More importantly republicans had no desire to clash with the church. That is why Seán T. O’Kelly could assure the Vatican in 1921 that the movement he represented were ‘Catholics as deeply religious as any others in the world … as practicing Catholics we have never allowed our national movement for independence to be contaminated by anti-religious or other dangerous movements condemned by the Church.’

Censorship and revisionism

In contrast Morrison’s account of life for northern nationalists after partition is one that most people in the south would probably agree with. In fact until the 1960s the traditional nationalist view of Irish history was the one taught in southern schools. Until 1972 at least sympathy with northern nationalists was general across southern society.

The generation of civil servants, policemen and politicians who clamped down on republicans after the early 1970s were products of a nationalist education system not a revisionist one. Why the south moved from sympathy to distance and even hostility is a complex issue, but there is more to it then censorship and revisionism. Numerous cliches about media hostility to republicans are cited, but the picture was far more diverse than this.

The Kevin Myers who poured abuse on republicans in the 1980s was the same Kevin Myers who resigned from RTE during 1972 in protest at Section 31. When Morrison claims that republicans ‘always sought dialogue’ he is being disingenuous. The IRA reiterated on numerous occasions that it would not settle for less than British withdrawal. As late as 1987 they stated that ‘the British will only be talked out of Ireland through the rattle of machine-guns and the roar of explosives.’

Danny Morrison himself was adamant in 1988 that ‘there’s going to be no IRA ceasefire. The only point in the IRA having a ceasefire or a permanent truce is if it is to facilitate British disengagement.’ But the context changes, as Morrison is well aware.

That is why the casual dismissal in The Good Old IRA of electoral mandates does not seem so clever now that Sinn Féin actually possesses them. If it was true, as republicans argued in the 1980s that ‘the IRA does not need an electoral mandate for armed struggle’ then what is to stop other republicans claiming the same today? Why can’t what Morrison refers to as ‘dissidents’ publish their own ‘Good Old (Provisional) IRA’?

No doubt the arguments about IRA’s, old and new, will continue. Indeed they resurfaced in November 2020 when Sinn Féin TD Brian Stanley tweeted that ‘kilmicheal (1920) and narrow water (1979)’ were ‘the 2 IRA operations that taught the elite of (the) British army and the establishment the cost of occupying Ireland.’

Republicans are right to ask whether they were abandoned by the south; but they might also ask why southern opinion shifted so decisively from sympathy with the northern struggle to hostility.

During the ensuing controversy Mary Lou McDonald suggested that what she called Stanley’s ‘ill judged … mistake’ had been his attempt ‘to draw historical comparison between something that happened in the ‘20s and something that happened in the ‘70s.’

But surely the whole point of The Good Old IRA was to draw those same comparisons? As it happens the media reaction to Stanley’s tweet was hysterical; people’s views on Warrenpoint were far more complex at the time than the condemnations suggested. They usually are. And they change over time. There is far more (rhetorical) support for the armed struggle now then there was when it actually taking place.

We live in an Ireland in which at least some young nationalists believe that the Cranberries Zombie is a rebel song. (It was actually written as a critique of the IRA after the Warrington bomb of 1993). So it might seem obvious that shooting a policeman in 1920 is exactly the same as shooting one in 1980. But the world in which the ‘old’ IRA operated was much more conducive to their success than that of the modern version. The most violent period of the War of Independence was effectively over after two years.

That war had a definable outcome which most of those living in the new Free State endorsed. The modern IRA’s war lasted for over 25 years and the result, a compromise which did not deliver a united Ireland, was empathically not what republicans had argued that all the violence, inflicted and endured, was for. Sinn Féin’s Declan Kearney has written about the need to have ‘uncomfortable conversations.’

These conversations should include the issues raised in Danny Morrison’s book. Republicans are right to ask whether they were abandoned by the south; but they might also ask why southern opinion shifted so decisively from sympathy with the northern struggle to hostility and ponder if the IRA itself played any part in that.