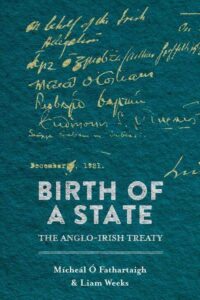

Book Review: Birth of a State, The Anglo-Irish Treaty

By Liam Weeks and Micheál O Fathartaigh

By Liam Weeks and Micheál O Fathartaigh

Published by Irish Academic Press, 2021

ISBN:9781788551595

Reviewer: John Dorney

Readers in Ireland (and many beyond) will need no reminding that December 6, 2021 marked one hundred years since the signing of the Anglo-Irish Treaty. The Treaty created the Irish Free State, the forerunner to today’s Republic of Ireland, while confirming the continued existence of Northern Ireland. The Treaty also, of course, ripped asunder a hitherto united Irish Republican movement and led to Civil War in the south in 1922-23.

In this book, a follow up to the volume they edited in 2018 – The Treaty – historian Micheál O Fathartaigh and political scientist Liam Weeks attempt to tell the story of the Treaty from its negotiation to its debate and passing the Second Dail, to its impact on party politics in independent Ireland; an attempt, they write, to present a comprehensive look at the Treaty in one volume.

They argue for the importance of the Treaty, noting that it is ‘under-appreciated’ and viewed as a ‘failure’ in popular consciousness, but the authors argue that it did lead to substantive independence and that in 1921 an all-Ireland sovereign republic was ‘never on the cards’ and that the Treaty was the inevitable result of ‘realpolitik’.

This should not be seen in moralistic terms, they argue, but Treaty should rather be viewed in a broader context, that of the treaties and new nation states that emerged after the ending of the Great War in 1918 and British Imperial policy.

The Treaty in international context

In this vein they suggest that the refusal of Eamon de Valera, President of the rebel Irish Republic declared in 1919, to approve the Treaty bears comparison with Phillip Schiedemann the President of the German Republic, who also refused to ratify the Treaty of Versailles in 1919.

Similarly, the partition of Ireland may bear comparison with that of India in 1947 and Palestine in 1948, which as the authors note created far more violent and to date insoluble conflicts than any seen in Ireland, which they suggest indicates that the fall out of the Treaty in Ireland ‘could have been very much worse’.

This book persuasively argues that the Treaty should not be viewed in moralistic terms but in those the realpolitik of the post Great War world

The Irish Free State, they note, for all of its problems, was one of only five democracies to survive the interwar period intact.

The comparisons with the new nation states of interwar eastern and central Europe such as Poland Czechoslovakia might perhaps have been explored in more depth. The League of Nations for instance, was committed to using plebiscites to determine boundaries, notably between Poland and Germany – a fact alluded to by the Irish Free State with regard to the Boundary Commission with Northern Ireland 1924-25, but which the Treaty of 1921 made no provision for.

The Treaty’s similarity with British Imperial peace-making in inter-war colonies and protectorates, notably Iraq and Egypt may also have deserved a look. Treaties concluded by Britain there in the 1920s, in a manner quite similar to Ireland, allowed for political self-government with a residual British presence, having secured British strategic, economic and military interests; the Atlantic ‘Treaty ports’ in Ireland, the Suez Canal in Egypt and the oilfields of Mosul in Iraq.

The book is more skilful, however in exploring how the Irish Free State fitted in to the increasing autonomy granted to fellow ‘white dominions’ of the British Empire; Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Newfoundland and South Africa. The chapter on this shows how, although the Irish Free State was quite unlike these British settler-colonies, in seeing itself as a suppressed nation striving for independence rather than a grateful child of Empire, its interests ran parallel to Dominions, especially Canada, which wished to govern their own affairs.

It is interesting that while many in the ‘loyal Dominions’ saw Irish nationalism as kind of ‘enemy within’ they nevertheless on the whole welcomed the Anglo-Irish Treaty, advancing as it did their aspirations for self-government within the Empire. Indian nationalists, like the Irish an outlier in rejecting imperial identity, unsurprisingly were particularly enthusiastic.

The authors are particularly interesting on Canada, noting that in 1922, despite having proudly served alongside Britain in the Great War, their Prime Minister refused Britain’s request to send troops to enforce the peace settlement on Turkey, setting an important precedent for the Dominion’s independence in foreign policy.

The Statute of Westminster in 1931, the authors note, which abolished the right of the Westminster Parliament to legislate for Dominions may not be celebrated in Ireland today but it marked the true achievement of Irish legislative independence.

Negotiations

The accounts of the Treaty’s negotiation are interesting and comprehensive. The authors defend Eamon de Valera’s strategy to hold himself back from the talks as a final arbiter, which could have worked, they argue, to extract final concessions from the British, but criticise him for allowing the talks to happen in London rather than on neutral ground and in failing to properly brief the Irish negotiating team of his intentions.

This contributed to the team and Michael Collins and Arthur Griffith in particular, losing faith in his leadership and going their own way.

The authors argue that the Irish negotiators could have done better on the issue of partition but extracted all that was possible in terms of the new Irish state’s sovereignty

Weeks and O Fathairtaigh argue that the Irish negotiators probably extracted as much as they could get with regard to the Free State’s sovereignty. The British were simply not prepared to allow the Free State to leave the Empire in 1921; such a precedent would have been viewed as too damaging for the Empire as a whole.

However, they criticise the negotiating team for not pressing home their moral advantage on redrawing the borders of Northern Ireland to allocate nationalist-majority areas to the Free State. Lloyd George, they argue knew that his case here was a poor one and might have given more ground on a Boundary Commission that would have had much more explicit terms to redraw the border including a plebiscite to consult the wishes of the inhabitants to border regions.

Lloyd George’s famous threat of war was indeed decisive in making the Irish negotiating team sign, but the authors argue that it was more than likely bluff and the Irish team should not have allowed themselves to be rushed into a decision.

The Debates

The chapter on ‘debating the Treaty’ notes the questionable democratic legitimacy of the Second Dail, being composed of just one party, Sinn Fein, all of whom had been elected unopposed in the election of May 1921 ostensibly to the Parliament of Southern Ireland (some, including the likes of Michael Collins, had also been elected in Northern constituencies, but only one TD did not also represent a Southern one).

There is a useful social profile of the 121 TDs who voted on the Treaty by age, political and military background, gender, religion and educational attainment.

The authors conclude that while the TDs by and large represented the membership of Sinn Fein, women (there were only 6 all of whom opposed the Treaty), Protestants (three, excluding converts to Catholicism who were 2-1 anti-Treaty) and both the upper and lower classes were all under-represented. The average TD was a Catholic of lower middle class origin, who was more likely than not to have had secondary education and far more likely than the general population to have been a member of the IRA and the Irish Republican Brotherhood.

The authors are also surely correct in noting that there was not a significant social or regional aspect to the Treaty split. At least not initially.

The methods of modern political science are used to analyse the debates, with various quantitive outcomes, including who spoke the most words (de Valera) whether the average TD made positive or negative arguments (negative), who used the most complex language (Erskine Childers, Michael Hayes, Eoin MacNeill and George Gavan Duffy for the record) and which words were most often used.

The Treaty debates are criticised as a missed opportunity to debate a new ‘social contract’ for an independent Ireland.

They note that while ‘Republic’ was uttered 1,200 times in the debates, ‘Ulster’ was mentioned a mere 113, indicating the priorities of the deputies. It was the sovereignty of the southern state rather than a united Ireland that took precedence in the debates.

The authors are critical of the debates themselves, calling them ‘fractious and bitter’ with the discourse ‘uninformed’ and many TDs taking the opportunity to ‘settle old grudges’ and lament that the debates compare unfavourably to, for example the American Constitutional Convention of 1787. No mention was made, they complain, of political philosophers such as Locke, Rousseau or Plato which might have informed a new ‘social contract’ and a ‘vision for a new democracy slipped from their grasp.’

The comparison with the United States’ founding debate seems unrealistic to this reviewer. The Irish deputies did have any liberty to debate the future form of the Irish state at the Treaty debates, merely whether or not to ratify the Anglo-Irish Treaty. And if they principally debated whether the Treaty would deliver substantive Irish independence that was because that was the sole content of the Treaty itself.

Some did bring up the social content of the prospective Irish state, Constance Markievicz for instance argued that a proposed upper house to represent Southern Unionists (rumoured to be in the prospective Free State constitution) would be a bulwark of ‘capitalists’ and ‘imperialists’ while pro-Treaty deputy Joe McGrath argued that the Treaty gave total freedom to enact the egalitarian Democratic Programme of 1919. However these debates inevitably lay in the future and were, not, probably could not have been, central to those over the Treaty.

IF the book has a weakness it is probably that it fails to get inside the mentalities of those involved in the Treaty debates. The substance of the pro-Treaty arguments as articulated by for example Arthur Griffith or Desmond Fitzgerald or Piaras Beaslai, that the Treaty delivered all the necessary attributes of sovereign statehood, of Richard Mulcahy that it was the best that could be achieved given the military situation, of Michael Collins and others that it was ‘freedom to achieve freedom’ are not forcefully articulated. Nor are the anti-Treaty ones, of Erskine Childers that that the Free State had no say in whether to enter future wars of Britain’s choosing, of Liam Mellows that the Treaty was an imposition by force of arms or Mary MacSwiney that it was a betrayal of the dead.

The authors may object that this would merely reproduce material found in their previous volume The Treaty. That may be so, but the reader will struggle to understand the emotional intensity of the split that, as the authors note, shaped much of the politics of independent Ireland.

This is also a strangely bloodless retelling of the Treaty split. No mention is made, for example that nearly 10% (12) of the TDs who voted on the Treaty died in or as a result of the ensuing Civil War. Several, including passionate anti-Treaty advocate in the debates, Liam Mellows, were executed by firing squad, and many more were imprisoned. The bitterness so caused was very real in independent Ireland and not merely histrionics or political stunt.

Similarly while it is true that questions such as the Oath of Allegiance to the constitution of the Free State (as yet undrafted) and to the British monarch took up more time than partition, this should be seen in a context where both pro and anti-Treaty sides were against partition and where Michael Collins, one of the authors of the Treaty, as well as arguing publicly that the Treaty itself would end partition, was already preparing to use clandestine force to end it. Moreover a significant number of anti-Treatyites, including Belfast born Sean McEntee did bring up the partition at length in the debates.

Noting that 24 TDs did not speak in the debates, the authors speculate that many ‘had little of substance to add’. One such TD Peter Paul Galligan is characterised as ‘drapers assistant from Cavan’. ‘Better to be thought a fool’ the authors speculate quoting Oscar Wilde, ‘than to open your mouth and remove all doubt’. He deserves better than this characterisation.

Galligan, did indeed work at one point as a draper’s assistant in Dublin prior to the 1916 Rising in which he was sent to command rebel forces in Enniscorthy. But in late 1921, fulltime revolutionary activist would be a better job description. He had since been imprisoned on three occasions, twice in solitary confinement and shot and wounded on his arrest in 1920. He was also one of the first Sinn Fein MPs elected in a by-election in Cavan in early 1918.

In 1921, Galligan was one of the few senior Republican figures whose release was insisted upon by the Irish side at the time of the Truce with the British in July of that year. That he did not speak in the Dail debates was not due to ignorance but to his closeness to both Michael Collins, his President in the Irish Republican Brotherhood and Eamon de Valera whom he voted to remain as President of the Republic even after voting for the Treaty.

The 18 Articles

The forensic examination of the Treaty’s 18 articles in the book’s penultimate chapter is useful and interesting, though to this reviewer’s mind, it does call into question whether the Treaty was such an exemplary settlement to ‘The Irish question’.

The authors note that had the Treaty been carried out to the letter, the Irish Free State could not issued its own passports, raised an army or navy over a certain quantity, remained neutral in any war that involved Britain and would have had to pay a very significant monetary debt to the British Empire. Moreover, the authors note that the framing of the Treaty and Oath of Allegiance meant that legally ‘Ireland would remain British’ – a startling echo of anti-Treaty arguments in the debates of 1921-22.

That all of these clauses were ultimately broken or amended by agreement may vindicate Michael Collins’ argument that the Treaty was a ‘stepping stone’ but surely cannot be used to argue for the excellence of the Treaty as a document in its own right. As, for instance, Harry Boland argued in the Dail debates, it was only by breaking the agreement that Irish aspirations for sovereignty could be reached.

The forensic examination of each of the Treaty’s 18 articles is useful and interesting.

Moreover, as the authors argue, had the result of the Boundary Commission in 1925 been known at the outset; i.e. that it would not shift the border at all, the Treaty may never have been passed. The Treaty’s provision for a Council of Ireland and possible incorporation of Northern Ireland under the Dublin government, they note, created the ‘erroneous’ interpretation that partition might be reversed under its terms. In fact, this was a political impossibility given the determined resistance of the Ulster unionists and their close alliance with the Conservative Party.

Given all of this, the anti-Treaty case, while not vindicated, becomes at least more comprehensible than the irrational fanaticism it is sometimes depicted as. The pro-Treaty case in fact involved very substantial revisions to the 1921 document also.

The authors conclude that the Treaty was a ‘let down’ for Irish nationalist and republicans in 1921 but that their hopes were ‘always going to be dashed’ and that one hundred years on ‘the time has come to commemorate, if not celebrate’ the Treaty.

This is a useful, well researched, accessible and interesting book should inform any mature reflections on that Treaty.