‘A Hard Bargain’ An Analysis of the Social and Economic Background of Kerry in the Early Twentieth Century

Life and work in County Kerry, 100 years ago. By Kieran McNulty

Sunday was “hiring–day” for the farmers and farm labourers gathered outside Saint John’s Church, Tralee when after 12 o’clock Mass the farmers would come along and test there prospective labourers to see if they were sound “in wind and limb” but most of all to drive a ‘hard bargin’ in getting their man as cheap as possible … After the “bargin” the farmer took away his man or boy for servitude covering a three-month, six-month or a year’s period.[1]

Paddy O’Brien, a former secretary of the Tralee branch of the Irish Transport and General Workers Union (ITGWU) [2]

This article is part of a wider research project I have undertaken over the last six years in relation to how the working-class of Kerry experienced the years 1913-23. Although this project is very much ‘a work in progress’, some of this research has already been published. It is therefore useful I would contend to analyse the social and economic conditions that prevailed in the county during this period, particularly by using the data from the Census of Ireland, County of Kerry, 1911 and Saorstát Éireann, Census of Population, 1926.

Between the Great Famine and Irish Free State’s first census in 1926, Kerry’s population had fallen from 293,880 to 149,171.

In the early twentieth century, Kerry was a predominantly rural society with an underdeveloped economy based largely on agriculture. From the time of the Great Famine to the First World War, Ireland’s population had fallen from in excess of eight million to 4.4 million[3] with the phenomenon of mass emigration becoming a recurring feature of the country’s demography during.

Similarly Kerry’s population had also been falling from 293,880 in 1841, to 149,171 in 1926.[4] Table 1 shows the decline in Kerry’s population during the years 1891-1926, but also reveals that by the early twentieth century this decline was beginning to slow down.

Table 1: Population Figures for Kerry – 1891-1926

| Year | Population | Decrease | Percentage Loss |

| 1891 | 179,136 | – | – |

| 1901 | 165,726 | 13,410 | 7.5 |

| 1911 | 159,691 | 6,035 | 3.6 |

| 1926 | 149,171 | 10,520 | 6.6 |

Source: Census of Ireland, 1911, County Kerry, (London, 1912), His Majesty’s Stationary Office;

Saorstát Éireann, Census of Population, 1926, (Vol. I), (Dublin, 1934), Department of Industry and Commerce,

(https://www.cso.ie/en/media/csoie/census/census1926results/volume1/C_1_1926_V1.pdf), (accessed 24 October 2019).

The evidence also indicates that urban development remained essentially uneven throughout the county with only 16.7 per cent of Kerry’s population living in towns with populations in access of 1,000.[5] Between 1891 and 1926 the phenomenon of urban growth was only witnessed as a consistent trend in the county’s largest town, Tralee as highlighted in Table 2:

Table 2: Population Figures for Tralee, Killarney and Listowel – 1891-1926

| Town | 1891 | 1901 | 1911 | 1926 |

| Tralee | 9,318 | 9,867 | 10,300 | 10,533 |

| Killarney | 5,510 | 5,656 | 5,796 | 5,323 |

| Listowel | 3,566 | 3,605 | 3,409 | 2,917 |

Source: Census of Ireland, 1911, County Kerry;

Saorstát Éireann, Census of Population, 1926,(Vol.1),

(https://www.cso.ie/en/media/csoie/census/census1926results/volume1/C_1_1926_V1.pdf), (accessed 24 October 2019).

By comparing the figures in Table 1 with those in Table 2 for the years 1891-1926, we can see that the population growth of Tralee, 13 per cent contrasts sharply with that of County Kerry which suffered a population loss of 16.7 per cent over the same period.[6] The major contributing factor to this population decline was the phenomenon of mass emigration.

Between 1901 and 1926 there were 88,094 births compared to 51,449 deaths in Kerry, a difference of some 36,595, yet the overall population of the county fell by 16,555.[7] In terms of gender, between 1901 and 1926 the male population of the county fell by 10,499, to 6,863.[8] One possible explanation for such a dramatic drop in the male population is the significant number of military deaths as a consequence of the First World War.

However, this explanation is somewhat inadequate, especially when one considers that Kerry had the lowest recruitment rate of men into the British armed forces in comparison to all the other counties of Ireland, and most estimates put the loss of life of Kerry men at the front at around 500.[9]

Between 1901 and 1926 the female population of Kerry dropped by 5,909 leaving 72,308 females resident in the county,[10] 4,555 less than the male population. Freeman suggests the main explanation for this pronounced difference in the male/female population is the migration trends from 1884, in which in general, ‘the female excess has been increasingly marked’ when compared to males.[11]

The greater part of the ongoing population decline, despite high birth rates, was caused by emigration. Women left in even higher numbers than men.

This is shown most dramatically in the decade 1891-1901 when 21,169 females emigrated compared to 17,430 males.[12] The most likely cause of this difference was that emigration afforded relatively greater career opportunities for young Kerry females by comparison to their male counterparts and lessened the pressure on women to marry and become housewives. Tom Doyle argues that ‘poverty was widespread in Kerry at this time’ and asserts that, ‘emigration … served as both an escape route and a safety valve for people whose life chances/employment prospects were slim’.[13]

There were also severe consequences for the Irish economy due to emigration as Karl Marx noted, ‘[T]he gap which emigration causes here, and limits not only local demand for labour, but also the incomes of small shopkeepers, artisans, and tradespeople generally’.[14] In February 1920 the RIC Inspector General also commented, ‘… the present condition of the country is not such as to encourage the investment of capital in industrial enterprise …’[15]

Limited Employment Opportunities

As illustrated in table 4 below, the 1911 census reveals that five times as many males as females were ‘gainfully’ employed in Kerry. By the 1926 census, the ratio of male to female employment in Kerry had been reduced to a ratio of 3:1.

Table 4: Male /Female Employment in Kerry 1911-26

| 1911 | 1926 | |

| Total in Employment | 56,936 | 61,928 |

| Males in Employment | 47,427 | 46,323 |

| Male Workers as % of Total in Employment | 83.33 | 74.63 |

| Total Female Employment | 9,509 | 15,605 |

| Female Workers as a % of Total Employment | 16.67 | 25.37 |

Source: Census of Ireland, 1911, County Kerry, (London, 1912), His Majest’s Stationary Office.

Saorstát Éireann, Census of Population, 1926, Occupations, ( Vol. II), (Dublin, 1934), Department of

Industry and Commerce.

https://www.cso.ie/en/media/csoie/census/census1926results/volume2/C_1926_V2.pdf (accessed

1 November 2019).

In 1926 there was 2,684 people in Kerry classified as ‘persons described as out of work’ which, out of a workforce 64,612, gives overall unemployment rate for the county of 4.15 per cent compared to the national rate of 5.57 per cent. The male unemployment figure for Kerry stood at 2,339 or 4.8 per cent of the male workforce, while there were 345 unemployed females, or 2.16 per cent of the female workforce.[16]

As already noted, one reason for the county’s low level of unemployment was its prevalent high rate of emigration. In the early twentieth century there was very little industry in Kerry, apart from the small number of textile firms based in Tralee including Revington’s Woollen Mills and Galvin’s knitting factory.[17]

The other major commercial concerns were owned by Donovan’s, Kellerher’s, Latchford’s and McCowen’s’. They exported ‘Kerry’s agricultural produce through Tralee and nearby Fenit and imported coal, maize and other goods from abroad’.[18]

Donovan’s owned two commercial enterprises in the town one of which supplied materials to the building and furnishing trades. Billy Mullins was employed by this firm which he describes as having,

… two very large saw mills, coal yard, and traded in cement, glass, anything and everything for building contractors and furnishers. They carried all types of farm implements, including mowing machines: hay cars and rakes, ploughs and pulpers.[19]

In regard to working conditions in, November 1915 the Workers’ Republic reported that at McCowen’s who were involved in the production of flour; two workers were killed as a result of work place accidents. The paper exclaimed ‘[O]ne cannot find words expressive enough to condemn the arrant church-going hypocrites …’[20]

Industrial employment existed in Kerry but was very limited – mainly to drapery, meat processing and printing.

Excluding drapery, (312 employees), in 1911 there were 2,119 people employed in ‘textiles, fabrics and dress’ in Kerry, 1,123 of whom were males.[21] On the 1926 census this category appears as ‘makers of apparel’ and employment in this sector had declined markedly to 1,378.[22] Other industries in Tralee included two bacon factories;[23] a printing and publishing business and drapers firms including the Munster Warehouse Company.

Another significant commercial concern in Kerry was centred on the economic activity of Fenit Port on Tralee Bay.

A canal linked the Basin dock area in Tralee to the Bay allowing marine traffic to navigate all the way to the edge of Tralee.

According to Paddy O’Brien, a former secretary of the Tralee branch of the Irish Transport and General Workers Union (ITGWU) when, the ‘smaller lighter steamers’ reached the Basin ‘dock and warehouses … it was then that the extremes of slave labour were revealed with men working into the small hours for a pittance’.[24]

The only other significant employment in Kerry at this time was in the fishing industry which had been in decline since the late nineteenth century and tourism.[25]

Agricultural Workforce

However, the single largest source of employment in Kerry was in the agricultural sector. As Table 5 below shows by 1926 agriculture employed 40,631 people, almost two thirds of the workforce.[26]

This increase is partly explained by the various agricultural reforms during the early twentieth century including the The Land Purchase Act 1903, commonly known as the Wyndham Act, enacted on 14 August 1903, and according to Bill Holohan ‘allowed for tenants in Ireland to purchase their estates from the landlords, with State assistance and subsidies’.[27]

Despite this increase however, the numbers of male as a proportion of the total number of workers employed in agriculture in Kerry actually fell sharply from 94.25 per cent in 1911, to 80.64 per cent by 1926, while there was an almost four fold increase in the numbers of females employed in this sector, mirroring the rapid growth in the female workforce in general throughout Ireland.

Table 5: Agricultural Workforce in Kerry 1911-26

| Employment Category | 1911 | 1926 |

| Total in Employment | 56,936 | 61,928 |

| Agricultural Workers | 34,366 | 40,631 |

| Agricultural Workers as a % of

Those in Employment |

60.35 | 65.79

|

| Male Agricultural Workers | 32,381 | 32,875 |

| Male Agricultural Workers as % of

Those in Employment |

56.82 | 53.19 |

| Male Agricultural Workers as % of

Total Agricultural Workers |

94.25 | 80.64 |

| Female Agricultural Workers | 1,985 | 7,756 |

| Female Agricultural Workers as % of

Total in Employment |

3.68 | 12.52 |

| Female Agricultural Workers as % of

Total Agricultural Workforce |

5.75 | 19.08 |

Source: Census of Ireland, 1911, County Kerry, (London, 1912), His Majest’s Stationary Office.

Saorstát Éireann, Census of Population, 1926, Occupations, ( Vol. II), (Dublin, 1934), Department of

Industry and Commerce.

https://www.cso.ie/en/media/csoie/census/census1926results/volume2/C_1926_V2.pdf

(accessed 1 November 2019).

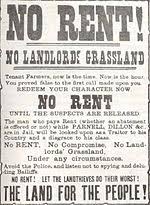

At the beginning of 1919 the simmering tension between labourers, organised by the ITGWU and farmers arising suddenly ignited into a violent conflict.[28] By the spring the County Inspector made reference to ‘the killing of animals’ and how, ‘bands of 50 to 80 men were roaming the county calling on farmers’ houses and taking out labourers who had not joined with them – some intimidation was used [resulting in] two cases to be tried by court martial’.[29]

Nearly two thirds of Kerry’s workforce worked in agriculture. Relations between farmers and labourers were often tense.

By the end of 1919 the focus of the farm labourer’s movement in Kerry was shifting to the demand, supported by the Transport Union, for ‘an extra acre’ of land to be granted by the farmers to each of the labourers who worked for them.

In Lixnaw on 25 January 1920, a meeting of ‘a very large and enthusiastic’ crowd was held to establish a committee of farm labourers.[30] When the farm labourers’ demands were rejected a virtual war developed, with the labours organising a boycott, sending threatening letters to farmers’ homes and burning their houses and crops. The farmers retaliated by shooting into the labourers’ cottages at night.[31]

Sinn Féin established Arbitration Courts and a Land Commission in an attempt to settle these disputes. These bodies however, invariably sided with the farmers. An example of the class bias common to many in Sinn Fein is displayed by the Minister for Home Affairs, the North Kerry T.D, Austin Stack, who declared that republicans were not about to allow ‘the mind of the people [to be] diverted from the struggle for freedom by a class war …’[32] Nevertheless Connor Kostick claims that the struggle of the rural labourers was ‘creating a climate of revolutionary change much deeper than that created by Sinn Féin’.[33]

Work, Gender and Class

In 1911 female workers made up less than one sixth of the county’s total labour force. Their position improved somewhat by 1926, when they accounted for a quarter of all workers in Kerry. In 1911 the largest number of females engaged in work outside the home was employed as domestic indoor servants (DIS’s), as maids, servants, housekeepers and similar occupations. Table 8, below, shows that in 1911 the DIS sector of Kerry’s economy was composed largely of female workers, and also illustrate just how important this sector of employment was for these workers.

Female participation in the workforce rose from one sixth to one quarter between 1911 and 1926.

By 1926 the numbers of females engaged as DIS’s in Kerry remained largely the same as in 1911, however, the female workforce had grown significantly in this period, while the male workforce engaged as DIS’s virtually disappeared. The numbers of female workers employed as DIS’s in Kerry decreased from almost half, to just over a quarter as a proportion of the total female workforce.

One reason for such a large representation of females employed in domestic service during the early twentieth century was that this type of work was seen as a natural extension of women’s traditional sphere of influence in the home.

Table 8: DIS Workforce in Kerry 1911-26

| 1911 | 1926 | |

| Total in Employment | 56,936 | 61,928 |

| Total DIS’s | 4,576 | 3,998 |

| Total DIS’s as a % of Total Employment | 8.04 | 6.46 |

| Total Male DIS’s | 343 | 85 |

| Total Male DIS’s as a % Total of DIS’s | 7.50 | 2.13 |

| Total Male DIS’s as a % of Total Male Employment | 0.96 | 0.18 |

| Total Female DIS’s | 4,233 | 3,913 |

| Total Female DIS’s as a % Total DIS’s | 92.50 | 97.87 |

| Total Female DIS’s as a % of Total Female Employment | 44.44 | 27.62 |

Source: Census of Ireland, 1911, County Kerry, (London, 1912), His Majest’s Stationary Office.

Saorstát Éireann, Census of Population, 1926, Occupations, ( Vol. II), (Dublin, 1934), Department of Industry and Commerce.

(https://www.cso.ie/en/media/csoie/census/census1926results/volume2/C_1926_V2.pdf ), (accessed 1 November 2019).

However, in the category of professional workers women were also disproportionately represented in comparison to men. In 1911 females accounted for – 971 out of 1,894, ‘all persons engaged in professional occupations’ (teachers, nurses etc.) representing 10.21 per cent of all female workers as compared to 1.95 per cent of all male workers.[34]

The 1926 census records a total of 2,010 workers engaged in the ‘professional occupations (teachers, &co.)’ of which females constituted a majority, 1,114,[35] but significantly this sector now only represented 7.10 per cent of all female workers as opposed to 1.93 per cent of all male workers. Again this was due mainly to the large numbers of women engaged in what was traditionally regarded as women’s work, the caring professions of teaching and nursing which accounted for significantly higher numbers of women than men.

By contrast in the upper middle class occupations women were grossly under represented. Of the 98 people employed in the legal profession in Kerry in 1911, none were female, and the same is also true of the county’s chartered accountants, civil engineers and surveyors.[36] By 1926 of the 68 doctors in the county only five were female and out of five barristers, only one was female.[37]

Women did however; make gains in the area of wealth creating enterprises. The 1911 census records a total of 659 ‘persons engaged in commercial occupations’, representing 1.16 per cent of Kerry’s workforce, of which only 73 are listed as female.[38] Apart from underlining the gross under-representation of women in the commercial sector, these figures also point to the underdeveloped capitalist economy of the county.

However, the 1926 census recorded a total of 2,800 people, or 4.52 per cent of the county’s workforce recorded engaged in ‘commercial, financial and insurance occupations’ of which 1,003 were females.[39] The census also registered 4,273 people as employers, or 6.90 per cent of the county’s workforce, of whom 805 were female, and included small businesses for example shopkeepers and hairdressers.[40] In 1911 middle class occupations, those engaged in work of a professional, or commercial nature (with the exception of shop assistants, bar workers, etc.) accounted for only 4,651 workers or 8.17 per cent of Kerry’s workforce.[41] By 1926 employment in this sector had only increased marginally.

Housing

The housing crisis was also a cause of the low standard of living experienced by the majority of the people in Kerry at the beginning of the twentieth century as is revealed in tables 9-10.

In 1911, as illustrated in table 10, the number of families living in single room accommodation in Kerry stood at 2,466, though by 1926 this figure had fallen by 45.19 per cent to 1,352. According to the 1911 census, on Francis Street, 203 people were living in 20 houses.[42]

Thomas Dillon describes how the rooms families were forced to live in ‘often … had no furniture and the family would have slept on the flour with straw for their bedding’.[43] While emigration was a significant factor in the relatively dramatic decrease in this population cohort during these years, other factors were also at play including the gradual replacing of slum housing with public housing thus relieving the county’s chronic housing crisis.[44]

While the accommodation crisis in Tralee had eased by 1926 there still remained 209 families living in one roomed accommodation in the town.

Tables 9 –11: Number of families occupying dwellings of less than five rooms, 1911-26.

Table 9: National

| One Room | Two Rooms | Three Rooms | Four Rooms | |

| 1911 | 51,451 | 148,887 | 181,123 | 100,887 |

| 1926 | 46,902 | 111,814 | 175,242 | 131,207 |

Table 10: Kerry

| One Room | Two Rooms | Three Rooms | Four Rooms | |

| 1911 | 2,466 | 9,626 | 8,608 | 3.,655 |

| 1926 | 1,352 | 6,638 | 9,052 | 5,799 |

Table 11: Tralee

| One Room | Two Rooms | Three Rooms | Four Rooms | |

| 1911 | 268 | 506 | 254 | 300 |

| 1926 | 209 | 440 | 479 | 343 |

Source: Source: Census of Ireland, 1911, County Kerry, (London, 1912), His Majest’s Stationary Office.

Saorstát Éireann, Census of Population, 1926, Housing, ( Vol. IV), (Dublin, 1929), Department of Industry and Commerce.

(https://www.cso.ie/en/media/csoie/census/census1926results/volume4/C_1926_Vol_4_entire.pdf),

(accessed 6 November 2019).

Health

Though poor housing conditions inevitably led to the rapid spread of contagious diseases including Tuberculosis (TB), in some respects Kerry’s population enjoyed better health relative to the majority of the rest of the nation’s population. From the Central Statistics Office survey, Life in 1916 Ireland, we learn that Kerry had an infant mortality rate per 1,000 population of 51.0 whereas the rate in Dublin City was 153.5.

To some extent the most extreme effects of poverty endured by the working-class were alleviated with the passing of a range of welfare acts. Despite this, in 1916 Kerry had one of the highest death rates in the country, with 2,003 deaths, 12.5 per 1,000.[45] Even with the passing of the Tuberculosis Prevention (Ireland) Act (1908), the general health condition of Kerry’s population continued to remain of a low quality.

Kerry had one of the highest death rates in Ireland, with tuberculosis among the main killers.

Between 1901 and 1911, 130,000 people in Ireland died from TB, and although Kerry’s average annual death rate for the years 1923-6, 11.9 per 1,000 population, was relatively low when compared to other counties, it is still high by modern standards.[46] In 1916 alone 280 people in Kerry died of TB, making the disease the single biggest cause of death in the county, above bronchitis and pneumonia (230).[47]

The scale of the TB pandemic is illustrated by the report of the chief county tuberculosis medical officer, Maurice Quinlan, for the year ending February 1914. During the year the medical officer ‘covered over 15,000 miles’ across Kerry and examined a total of 234 cases of TB only 90 of whom were covered by health insurance and only just ‘ten have been cured’, figures broadly in line with the national averages, but significantly higher than those of Britain or Europe.[48] In summing up his report on T.B. in Kerry, the chief medical officer made the following observations:

Because T.B. in its onset is insidious and because change from health to ill health and death is slow and gradual and we have become familiarized with the presence of T.B. in our midst … we hitherto have not made any serious resistance to the enemy, but rather have taken the fate of our relatives, friends and neighbours attacked by the disease, as inevitable … And the pity of it all is, that practically all this is preventable and curable and also it is not hereditary – but is contagious. Health education is vital. For the last sixty years deaths from this disease have come down steadily and surely in all European countries except Ireland.[49]

In the early twentieth century in the United Kingdom, of which Ireland was then a part, there was a two tier health system. For the wealthy there was private health care ‘paid for by upper and middle-class philanthropists and staffed by doctors who treated patients for free’,[50] but for the poor there was only the workhouse.

In Kerry the republican revolutionary and feminist, Gobnait Ní Bhrudair despite the best efforts of the Catholic Church and the medical establishment and both the British Government and the Free State regime [51] finally managed to rase financial support for a hospital for Tralee where the town’s workhouse was converted into Saint Catherine’s Hospital. [52]

There was also Killarney Mental Hospital communally known as Killarney lunatic asylum which contained many people who were not in any way mentally ill while those who were genuinely unwell often suffered what we would regard today as serious human rights abuses. [53]

In 1911 in an attempt to improve this situation, the Government introduced a form of health insurance linked to dispensary doctors. On foot of Maurice Qunlan’s report Kerry County Council passed a resolution ‘calling for effective measures to be taken to make sure that everyone in the county is covered by the health insurance scheme’.[54]

Religious Affiliation

In terms of religious observance, the 1911 census recorded 155,322 people, or 97.2 per cent of Kerry’s population as Roman Catholic with the remainder as those belonging to the Protestant faiths, 4,255 of which the Church of Ireland representing by far the largest denomination.[55] By the time of the 1926 census Catholics accounted for 98.4 per cent of Kerry’s population with Church of Ireland numbers falling dramatically from 3,725 in 1911, to 2,051 by 1926.[56] These population trends are broadly in line with those of the Twenty Six Counties as a whole.[57]

Kerry’s Protestant population was small and fell dramatically between 1911 and 1926.

Numerous explanations have been put forward in regard to the rapid fall in the Protestant population in these years, including sectarian violence and deaths at the Front during the First World War.

However, historian Diarmaid Ferriter is sceptical of this line of argument. He points out that their, ‘decline, however … had begun with the Land War of the nineteenth century and especially the Wyndham Act of 1903, and entered its last days when the First World War began’.[58] Another possible reason for the fall in the Protestant population was that many felt distinctly uncomfortable under the dominant influence of the Catholic Church in the new Free State as Kieran Allen has observed,

After independence, the Catholic Church acquired a special role in enforcing moral control over the population … Once the counter-revolution was successful; [the government] cemented the alliance with the bishops by passing sectarian legislation that brought the state into conformity with a Catholic ethos.[59]

While there was a significant exodus of Protestants from Kerry and indeed Southern Ireland in general, both during and after the ‘Troubles’, it also needs to be stressed that there were a multiple possible explanations for this phenomenon.

Conclusion

http://www.mayolibrary.ie/en/LocalStudies/Emigration/Family/

Kerry situated in the remote south westerly corner of Ireland, in the early twentieth century consisted of a sparse, declining and predominantly rural population that was overwhelmingly Roman Catholic. The prospects for social and economic advancement for the majority of the county’s population were limited.

For male workers employment opportunities lay predominately in agricultural labour. The only other viable alternative for these young men was emigration.

The prospects for Kerry’s female population were, if anything, even more limited. The choice facing most women, often after a period as domestic servants, was either marriage and thereby giving up all hope of paid employment or else to also emigrate which they did in even greater numbers than the males. Kerry’s economy was also significantly underdeveloped by western European standards.

Consequently all the comparable major socio-economic factors provide compelling proof that the working-class and peasantry, by far the majority of Kerry’s population, suffered a depressed standard of living resulting in a poor quality of life and for females this was even more so the case. Therefore the only realistic choice for the majority of Kerry’s population was either a life of poverty or emigration.

References

[1] This article is a revised version of an article, The Social and Economic Background of Kerry in the Early Twentieth Century, Saothar 46, 2021. It is just over two thirds the length of the original article, fresh detail has been added and some the empirical data has been corrected in the light of further research.

[2] Liberty, June 1981.

[3] Gearóid Ó Tuathaigh, Ireland Before the Famine, 1798-1848, (Dublin, 1984), Gill and Macmillan, p. 129;

Joseph Lee, The Modernisation of Irish Society, 1848-1918, (Dublin, 1984), Gill and Macmillan, p. 1.

[4]. Saorstát Éireann, Census of Population, 1926, (Vol. 1), (Dublin, 1934), Department of Industry and Commerce, p.25.

https://www.cso.ie/en/media/csoie/census/census1926results/volume1/C_1_1926_V1.pdf (accessed 24 October 2019).

[5] Ibid., p. 13.

[6] Census of Ireland, 1911, County Kerry, p. 2, Saorstát Éireann, Census of Population, (Vol.1), p. 25.

https://www.cso.ie/en/media/csoie/census/census1926results/volume1/C_1_1926_V1.pdf (accessed 24 October 2019).

[7] Census of Ireland, 1911, County Kerry, pp.1-2, 76; Saorstát Éireann, Census of Population, Vol.1), p. 133-4.

https://www.cso.ie/en/media/csoie/census/census1926results/volume1/C_1926_V1.T6.pdf (accessed 25 October 2019).

[8] Census of Ireland, 1911, County Kerry, pp. 1, 2, Saorstát Éireann, Census of Population, 1926, (Vol. 1), p. 10. https://www.cso.ie/en/media/csoie/census/census1926results/volume1/C_1926_V1.T6.pdf (accessed 25 October 2019).

[9] Kieran McNulty, ‘Working Class Radicalism in Tralee’, 1914-1918, Saothar 42, 2017, pp. 43-52.

[10] Census of Ireland, 1911, County Kerry, pp. 1, 2, Saorstát Éireann, Census of Population, 1926, (Vol.1), p. 10. https://www.cso.ie/en/media/csoie/census/census1926results/volume1/C_1926_V1.T6.pdf (accessed 25 October 2019).

[11] Freeman, The Changing Distribution of Population in Kerry and West Cork, p. 30.

[12] Census of Population, Kerry, 1911, p. 167.

[13] Tom Doyle, The Civil War in Kerry, p. 14.

[14] Karl Marx, Capital: A Critique of Political Economy, (New York, 1906), The Modern Library, p. 775.

[15] PRO London/NLI, CO (Colonial Office Papers for Ireland) 904/105, RIC Inspector General’s (IG) Report for Ireland, February 1920, p. 279.

[16] Saorstát Éireann, Census of Population, 1926, Industrial Status, ( Vol.VI), (Dublin, 1931), Department of Industry and Commerce, p. 26.

https://www.cso.ie/en/media/csoie/census/census1926results/volume6/C_1926__Vol_6_entire.pdf (accessed 27 November 2019).

[17]. Billy Mullins, Memoirs of Billy Mullins: Veteran of the War of Independence, (Tralee, 1983), Kenno Ltd., p. 189.

[18] Crean, ‘The Labour Movement in Kerry and Limerick’, p. 31.

[19] Mullins, Memoirs of Billy Mullins, pp. 189-90.

[20] Workers’ Republic, 20 November 1915.

[21] Census of Ireland, 1911, County Kerry, pp. 82-93.

[22] Saorstát Éireann, Census of Population, 1926, Occupations, ( Vol. II), (Dublin, 1934), Department of Industry and Commerce, p. 20. https://www.cso.ie/en/media/csoie/census/census1926results/volume2/C_1926_V2.pdf (accessed 1 November 2019).

[23] Liberty, June 1981.

[24] Liberty, June 1981; see also Mullins, Memoirs of Billy Mullins, p. 189

[25] Freeman, The Changing Distribution of Population in Kerry and West Cork, p. 37.

[26] Saorstát Éireann, Census of Population, 1926, Occupations, (Vol.II), pp. 144-45. https://www.cso.ie/en/media/csoie/census/census1926results/volume2/C_1926_V2.pdf (accessed 1 November 2019).

[27] Bill Holohan, Solicitor & Senior Counsel, https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/land-purchase-act-wyndham-enacted-14-august-1903-allowed-bill-holohan/ [accesses 21 December 2021].

[28] Kieran McNulty, ‘War and the Working-class in Kerry 1919-1921’ in Saothar 45, 2020), pp. 87-97; Kieran McNulty, ‘Working-Class Radicalism in Tralee, 1914-1918’, in Saothar 42, 2017, pp. 43-52.

[29] CO 904/108, March 1919, pp. 699-700.

[30] Kerryman, 31 January 1920.

[31] J. Anthony Gaughan, Austin Stack: portrait of a separatist, (Dublin, 1977), Kingdom Books, pp. 134-5.

[32] Mike Milotte, Communism in Ireland: the pursuit of the workers’ republic since 1916, (Dublin, 1984) Gill and Macmillan, p .32.

[33] Conor Kostick, Revolution in Ireland: Popular Militancy 1917-1923, (Cork, 2009), Cork University Press, p. 124.

[34] Census of Ireland, 1911, County Kerry, p. 82.

[35] Saorstát Éireann, Census of Population, 1926, Occupations, (Vol.II), pp. 144-5. https://www.cso.ie/en/media/csoie/census/census1926results/volume2/C_1926_V2.pdf (accessed 1 November 2019).

[36] Census of Ireland, 1911, County Kerry, p. 82.

[37] Saorstát Éireann, Census of Population, 1926, Occupations, (Vol. II), pp. 77-8. https://www.cso.ie/en/media/csoie/census/census1926results/volume2/C_1926_V2.pdf (accessed 19 November 2019).

[38] Census of Ireland, 1911, County Kerry, pp. 82-5.

[39] Saorstát Éireann, Census of Population, 1926, Occupations, (Vol.II), pp. 74-5. https://www.cso.ie/en/media/csoie/census/census1926results/volume2/C_1926_V2.pdf (accessed 21 January 2020).

[40] Saorstát Éireann, Census of Population, 1926, Industrial Status, (Vol. VI), p. 26.

https://www.cso.ie/en/media/csoie/census/census1926results/volume6/C_1926__Vol_6_entire.pdf (accessed 27 November 2019).

[41] Census of Ireland, 1911, County Kerry, p. 82.

[42] Census of Ireland 1901/1911, National Archives, Census of Ireland, 1911, as cited by Thomas Dillon, Lecture given at Kerry County Library, Tralee on 28th April 2016 as part of the Letters of 1916 event, Poverty and War: County Kerry and the letters from 1916, (NUI Maynooth, 10 April 2018), http://letters1916.maynoothuniversity.ie/wp-post/poverty-and-war-county-kerry-and-the-letters-from-1916 (accessed 6 October 2021).

[43] Dillon, Lecture given at Kerry County Library, 2016

[44] Kerry People, 1 April 1922.

[45] Census of Ireland, Kerry, 1911, p. 160, Life in 1916 Ireland: stories from the statistics, table 3.3 Infant mortality rates, 1911, https://www.cso.ie/en/releasesandpublications/ep/p-1916/1916irl 9 (accessed 23 January 2020).

[46] Maurice Quinlan, Chief County Tuberculosis Medical Officer, Medical Report, 14 Feb., 1914, Kerry County Council Minutes, 1913-18, pp. 159-60; Saorstát Éireann, Census of Population, 1926, Population, Areas, and Valuations of each Electorial Division and each large Unit of Area, ( Vol. I), (Dublin, 1928), Department of Industry and Commerce, pp. 131-6. https://www.cso.ie/en/media/csoie/census/census1926results/volume1/C_1_1926_V1.pdf (accessed 28 November 2019).

[47] Census of Ireland, Kerry, 1911, p. 160; Life in 1916 Ireland: stories from the statistics, table 3.7 Deaths and death rates, 1916. Rates 1911, https://www.cso.ie/en/releasesandpublications/ep/p-1916/1916irl (accessed 23 January 2020).

[48] Quinlan, Medical Report, Kerry County Council Minutes, 1913-18, pp. 159-60, pp. 159-60; Saorstát Éireann, Census of Population, 1926, Population, Areas, and Valuations of each Electorial Division and each large Unit of Area, (Vol. I), p. 72.

[49]. Quinlan, Medical Report, Kerry County Council Minutes, 1913-18, pp. 159-60.

[50] theconversation.com/what-was-healthcare-like-before-the-nhs-99055 [accessed 21 December 2021],

[51] Margret Ward, Unmanageable revolutionaries: women and Irish nationalism, (London, 1995), Pluto Press, p. 34.

[52] Owen O’Shea and Gordon Revington, A Century of Politics in the Kingdom, (Newbridge, 2018), Merrian Press, p. 34.

[53] Radical Ruins, 8 November, 2017, http://aftersantacruz.blogspot.com/2017/11/feminist-and-revolutionary.html [accessed, 21 August, 2020].

[54] Kerry County Council Minutes, 1913-18, p. 160.

[55] Census of Ireland, Kerry, 1911, p. 113.

[56] Census of Ireland, Kerry, 1911, p. 153; Saorstát Éireann, Census of Population, 1926, Part I.-Religions, Part II.-Birthplaces, (Vol. III), (Dublin, 1929), Department of Industry and Commerce, p. 10.

https://www.cso.ie/en/media/csoie/census/census1926results/volume3/C_1_1926_V3.pdf (accessed 24 November 2019).

[57] Ibid, pp. 1-15.

[58] Diarmaid Ferriter, A Nation and not a Rabble, pp. 289-91.

[59] Kieran Allen, 1916: Ireland’s Revolutionary Tradition, (London, 2016), Pluto Press, pp. 112-3.