Albert Cashier, the woman who fought as a man for the Union.

By John Joe McGinley

By John Joe McGinley

There are over 400 documented cases of women disguising themselves as men to fight for both the Union and the Confederacy in the American Civil War. One of the most famous female soldiers of the American Civil War was Jennie Hodgers, an Irish-born immigrant, who enlisted as Private Albert Cashier and was who served in the Union Army during the conflict.

The story of Cashier is one of the most notorious, because Albert continued to live as a man long after the war and the secret was not discovered until just before his[i] death. This nearly lifelong commitment to a male identity, has led historians to now classify Cashier as a transgender man. (1)

Leaving Ireland for America

Albert Cashier was born Jennie Hodgers on December 25th, 1843 in Clogherhead, County Louth to Sallie and Patrick Hodgers.

Not much is known of her early life as the only documented account of her life was given when she was suffering from the onset of dementia in 1913.

Jennie Hodgers, originally of Co Louth, was forced by her uncle to pretend to be a boy, Albert Cashier to obtain employment in an all-male shoe factory

Jennie Hodgers left Ireland as a stowaway. On her arrival in America, she eventually moved to Illinois where her uncle forced her to pretend to be a boy to obtain employment in an all-male shoe factory. Albert Cashier was born.

Jenny, now living as Albert, finally settled in Belvidere Illinois and continued living as a man and worked as a labourer, farmhand, and shepherd for a farmer named Avery. (2)

Joining the Union Army

When the civil war broke out, Albert was still living in Belvidere and she witnessed many of the male inhabitants march off to defend the Union as part of the Fifteenth Illinois Infantry regiment.

Many of these men died at the Battle of Shiloh (also known as the Battle of Pittsburgh Landing) which was one of the first battles in the Western Theatre of the conflict, fought April 6th and 7th, 1862, in south western Tennessee.

Due to the escalating nature of the Civil War and the climbing casualties, President Abraham Lincoln sent out a call for 300,000 additional men to serve in the Union Army. Though born a woman Jennie Hodgers, Albert Cashier, still living as a man, joined many of his fellow citizens and took the train to Rockford to take part in fighting the Confederacy.

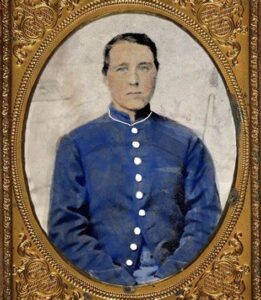

While living as the man, Albert Cashier, the Irish immigrant born as Jennie Hodgers, enlisted in the Union army in August 1862.

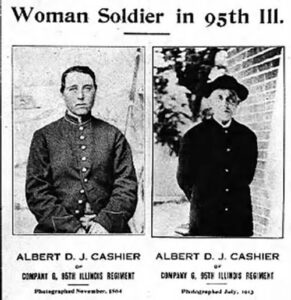

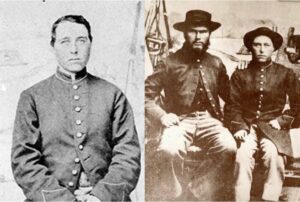

On the 6th of August 1862 Albert enlisted in the Union army as private Albert D J Cashier in company G of the 95th Illinois infantry regiment. Albert could not read or write so he marked an X on the enlistment papers and even passed a cursory physical examination.

Standing only 5 feet three inches tall, Albert was under nourished and slight, but this was not unusual for the time and many other Irish American soldiers were in similar shape. Albert was listed on the company roster as:

“Nineteen and small in stature” (3)

Other soldiers noted that Albert kept his own company and preferred to bathe alone.

However, Cashier was accepted in the regiment as “one of the boys” and considered to be a good soldier and excellent shot.

The 95th Regiment was mustered into Federal service at Camp Fuller, Illinois, on September 4th, 1862. A month later they made their way to Grand Junction, Tennessee, where it became part of General Ulysses S. Grant’s Army of the Tennessee, originally assigned to the 1st Brigade, 6th Division, XIII Corps.

Albert would participate in over 40 battles as the regiment travelled a total of 9000 miles across the landscape of war.

Albert would participate in over 40 battles as the regiment travelled a total of 9000 miles across the landscape of war.

In all the regiment marched 1,800 miles and was transported by riverboat and rail a further 8,200 miles. (4)

In May 1863, Private Cashier participated in the Siege of Vicksburg, during which time he was captured while performing a reconnaissance mission. He escaped by wrestling a gun away from her Confederate jailer and beating him senseless. Albert was pursued but managed to reach the safety of the Union lines.

After the Battle of Vicksburg, in June 1863, Cashier contracted chronic diarrhoea and entered a military hospital, somehow managing to evade detection as a woman.

Throughout the war Albert corresponded by letter with the family of his old employer and they once asked her if she had bought a dress for her sweetheart.

In the spring of 1864, the regiment was also present at the Red River campaign under General Nathaniel Banks, and in June 1864 at the Battle of Brice’s Crossroads in Guntown, Mississippi. This was to prove the deadliest engagement of the war for Albert and his comrades. In scorching heat, the regiment was called upon to support the Union lines under heavy Confederate pressure. While many men fell out of the ranks due to heat exhaustion, many more fell to rebel bullets.

After the 95th formed its battle line their commander Colonel Humphrey was killed. Command devolved onto Captain William H. Stewart of Company F, but after a few minutes he was shot through both thighs. Then Captain Elliot Bush of Company G took command, but he too was killed. Finally, Captain Almon Schellenberg took command and managed to hold the regiment together as Confederates swarmed around both left and right flanks.

The 95th held the line for about two hours but the Confederate assault was too much and the 95th Illinois, along with the rest of the Union forces, fled from the battlefield. The Battle of Brice’s Crossroads cost the 95th Illinois regiment one-third of its strength in killed, wounded, and missing. (5)

During 1864, the 95th pursued Confederate General Sterling Price during his Missouri raid.

In December 1864, they fought at the Battle of Nashville, the last major battle in the Western Theatre.

They were then sent to the Gulf of Mexico, where the regiment ended its military service by taking part in the siege and capture of Spanish Fort and Fort Blakely in March 1865.

Cashier served a full three-year enlistment with his regiment until they were all mustered out on August 17th, 1865 after losing a total of 289 soldiers to death and disease. (6)

Even well after the war Albert’s comrades remembered the slight soldier as a brave fighter, admired for heroic actions and undertaking dangerous assignments, yet never receiving a scratch.

Life as a man after the war

While Albert’s war service is an astounding story, his life afterwards is even more intriguing.

While Albert’s war service is an astounding story, his life afterwards is even more intriguing.

Albert had escaped the war without serious injury, allowing him to keep his biological gender a secret. He was mustered out of the Union Army along with the remainder of her regiment on August 17th, 1865.

The woman born as Jennie Hodgers had served three years and 11 months as the man Albert Cashier, in the ranks of the Union army. He had marched the length and breadth of America, fought in over 40 battles and earned a reputation among fellow troops as a brave soldier who was a crack shot and tenacious under fire.

The surviving men of the 95th returned home to Illinois and received a hero’s welcome.

Albert returned to Belvedere continuing to live as a man. His secret still undiscovered.

In 1869 Cashier moved to Saunemin Illinois. There Albert worked as a farmhand as well as performing odd jobs around the town and can be found in the town payroll records. Cashier lived with his employer Joshua Chesbro and his family in exchange for work.

Albert earned a reputation among fellow troops as a brave soldier who was a crack shot and tenacious under fire. After the war he continued to live as a man.

In 1885, the Chesbro family had a small house built for Cashier. Albert continued his identity as a man, and held many different jobs, including church janitor, cemetery worker, and street lamplighter. Cashier also voted in elections at a time when women did not have the right to vote.

Albert applied for a veteran’s pension in 1899, but did not complete the process until 1907, since it required a medical exam. Somehow, Cashier convinced the examining board not to divulge his secret and the pension was finally granted. (7)

Despite a reputation for being an eccentric, Albert was well liked and in later years took to having his meals with the neighbouring Lannon family. The Lannons discovered their friend’s gender of birth when Cashier fell ill, but decided not to make their discovery public.

Albert’s secret revealed.

Albert often carried out odd jobs for State Senator Ira Lish and in November of 1910, he was at work picking up sticks in the Senators driveway. Cashier was hit by the reversing Senator’s car and broke his leg. Senator Lish later claimed he did not see Albert due to her slight frame.

Taken to hospital a doctor discovered his birth gender while examining his leg. Albert implored the doctor and the shocked Senator to protect her long-held secret and they agreed to help him. It must be remembered this was a soldier with a pension who had voted in numerous elections. Had the secret been revealed, not only would the pension be revoked, but Albert would be charged with electoral fraud.

After falling ill in 1910, Albert’s gender of birth was discovered

Everyone decided that no good would be served by making his biological gender public knowledge.

Albert never recovered fully from the accident, and within months, the Senator and the doctor agreed that he needed institutional care, because he was now unable to work or look after himself.

On May 5th, 1911, he was moved from Saunemin to the Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Home in Quincy, Illinois, where he was admitted as a man. While the staff was aware of Cashier’s double life, they never broke their confidence.

In 1913, the US government attempted to charge Private Albert Cashier with defrauding the government to receive a pension, but his war comrades rallied around him.

Cashier remained a resident of the home until March of 1913, when due to the onset of dementia, he was sent to a State hospital for the Insane at East Moline, Illinois. This required a court hearing, and although her gender was not referred to at the hearing, word soon got out and the excited press broke the sensational story. (8)

The US government then decided to charge Private Albert Cashier with defrauding the government to receive a pension.

An investigation was launched, but luckily her comrades from the 95th Illinois rallied and testified that this was not Jennie Hodgers but Albert Cashier, a small but brave soldier.

Man or woman, this soldier had indeed shown bravery on dangerous missions. In the end, Albert/Jennie was awarded veteran status and a pension for life.

However, at the hospital, Albert was forced to wear dresses for the first time in more than 50 years. Cashier fought back for a long time before finally giving in.

Death and remembrance

Many of Albert’s former comrades, although initially surprised at the revelation of his long-held secret, were supportive of Cashier, and protested at his treatment at the state hospital.

Many of Albert’s former comrades, although initially surprised at the revelation of his long-held secret, were supportive of Cashier, and protested at his treatment at the state hospital.

Albert was now 67 years old frail and in advanced stages of dementia, he was unaccustomed to walking in women’s clothing, one day she tripped and broke her hip.

Unfortunately, he never recovered from the injury and spent the rest of her life bedridden.

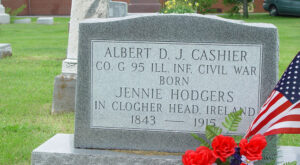

Albert Cashier died at the Watertown State Hospital on October 10th, 1915. He was given an official Grand Army of the Republic funerary service in East Moline on October 12th and was buried with full military honours.

In death Albert abandoned her dresses and wore the Union uniform, of which he was so proud, with casket draped with an American flag.

Albert’s tombstone showed his male identity and military service. “Albert D. J. Cashier, Co. G, 95 Ill. Inf.

Albert’s tombstone showed his male identity and military service. “Albert D. J. Cashier, Co. G, 95 Ill. Inf.

It took W.J. Singleton, executor of her estate, nine years to track Cashier’s identity back to Jennie Hodgers. The people of Saunemin have not forgotten their brave soldier of the Civil War. On Memorial Day, 1977, they erected a larger monument that bears both her names, near the first one at Sunny Slope cemetery in Saunemin, Illinois. (9)

What distinguishes Albert from most of the other women who fought in the American Civil War is that his secret was not discovered during the conflict.

Even in the cases where these women were found out as soldiers, there does not actually seem to have been much uproar. They were mostly just sent home or allowed to serve as nurses in field hospitals.

The situations in which they were found out were often medical conditions; they were injured, or they had fallen ill from dysentery or chronic diarrhoea.

As for Albert, no matter if called Jennie Hodgers or by her chosen name for over 50 years, Albert Cashier, one thing is certain. He or she was a true patriot, an upright citizen and a person loved and respected by those who touched her life.

John Joe McGinley May 2021

Sources:

- Bonnie Tsui, she went to the field, women soldiers in the Civil War.

- The Irish Times, 10th 2018

- Bonnie Tsui, she went to the field, women soldiers in the Civil War.

- Irish Central Albert Cashier October 2020

- Edwin C Bearss. “Protecting Sherman’s Lifeline: The Battles of Brices Crossroads and Tupelo 1864”. 1971

- Thomas Yoseloff, A Compendium of the War of the Rebellion. 3 vols. New York: 1959.

- “The Handsome Young Irishman of the 95th IL Infantry”. eHistory, Ohio State University. Retrieved August 3, 2018.

- Bonnie Tsui, she went to the field, women soldiers in the Civil War.

- For Love of Freedom”. Saunemin Historical Society. July 2012.

[i] Note: when referring to Jennie Hodgers, this article will use the pronoun ‘her’. When referring to Albert Cashier it will use ‘him’.