Book Review: Mary J. Murphy, Achill Painters – An Island History

By Mary J. Murphy

By Mary J. Murphy

Publisher: Galway: Knockma Publishing, 2020.

Reviewer: Patricia Byrne

The lure of Achill

On 30 October 1918 a young artist/illustrator and nationalist activist, Cesca Trench, died in Dublin at the age of twenty seven having fallen Achill, paintersvictim to the flu epidemic sweeping across Europe. Six months previously she had married Diarmuid Coffey, a member of the Irish Volunteers, whom she first met on Achill Island several years earlier while both attended Scoil Acla, one of a series of Gaelic League summer schools of the period which were focal points for cultural nationalism as part of the Irish Revival.

A century after Cesca Trench’s untimely death, as another pandemic Covid 19 enveloped the country, an unusual drive-in book launch took place at Dooagh, Achill, as wind gusts and rain descended on the attendees. It was the launch of Mary J. Murphy’s Achill Painters and the event was organised under the auspices of Scoil Acla, (the summer school having been revived in 1985) which was unable to host its usual summer programme of music, dance, literature and arts due to the Covid restrictions.

The book hinges on the life of Eva O’Flaherty (1874-1963), who was a magnet for artistic and creative networking on Achill in the first half of the twentieth century

The relationship of artists with Achill Island was particularly intense in the early decades of the twentieth century, especially through the figure of Paul Henry who spent almost a decade on the island from 1910 and whose idyllic landscapes became iconic in post-Independence Ireland. However, the artistic pull of Achill Island stretches back almost two hundred years and deep into the early nineteenth century.

Romantic painters such as William Evans produced island scenes in the 1830s and featured in the Irish travel books of Samuel and Anna Hall.

In Achill Painters – An Island History, Mary J Murphy doesn’t aspire to track or summarise two centuries of artistic activity on Achill. Rather, her particular focus is clarified on page 1, where she speaks of gathering ‘the stories of Belgian Expressionist Marie Howet & Art Doyenne Eva O’Flaherty’. The book hinges on the life of Eva O’Flaherty (1874-1963), who was a magnet for artistic and creative networking on Achill in the first half of the twentieth century, as well as on Marie Howet (1897-1984), the Belgian expressionist painter who visited the island on and off from 1929. Howet’s painting depicting a village scene in Dooagh, Achill, gives the book its striking cover image.

Eva O’Flaherty

Mary J. Murphy is also the author of Achill’s Eva O’Flaherty: Forgotten Island Heroine (2012) which details the founding of Scoil Acla in 1910 by Anita McMahon, Claude Chavasse, Darrell Figgis, Eva O’Flaherty, Emily Weddall and others.

Like other Gaelic League summer schools of the period, Scoil Acla attracted interest from a revolutionary generation, which included the Trench sisters, who aspired to a reimagined Ireland culturally and politically.

Scoil Acla’s early years also coincided with artists Paul Henry, Grace Henry and Robert Henri making Achill their home and being heavily influenced artistically by the island landscape and people. All three artists had spent time in Paris and were influenced there by the new movements in Naturalism, Realism and Impressionism.

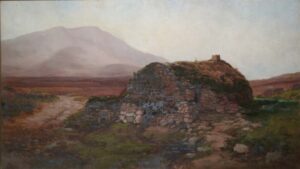

Alexander Williams’ Achill cottage set against the background of Slievemore evokes post-Famine scenes of absence, displacement and deprivation.

Eva O’Flaherty studied millinery in Paris, ran a millinery shop in London and, on moving to Achill in 1910, opened St Colman’s Knitting Industries which provided employment for local women for almost fifty years. Mary J. Murphy highlights the fact that Eva, alone among the Scoil Acla founding group and other artist visitors to Achill in that period, remained on the island to make her living and to improve the material conditions of the people, combining her business with skilful networking on the lines of an artistic salon at her home in Dooagh.

The author emphasises the Achill social activism not just of Eva O’Flaherty in her business venture, but also of Scoil Acla co-founders Anita McMahon, a journalist, and Emily Weddall, a nurse, who were prominent in supporting tenants during Achill land agitation in 1912 and 1913.

These were also the years in which the artist Grace Henry cut a forlorn figure over almost a decade when she lived with her husband on the island and where she appeared depressed and unhappy. She painted numerous night scenes and was bolder than her husband in experimenting with her painting style. After the Henry marriage ended, Grace Henry was overshadowed by her husband whose work was widely disseminated through posters, prints and photographs in the young Irish state.

Nineteenth Century

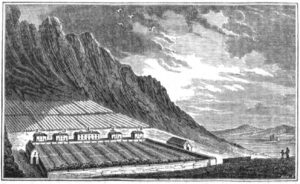

While Achill Painters largely focuses on the twentieth century, there are references to Edward Nangle and his Achill Mission Colony development which, together with the Great Famine, were the two dominant episodes in nineteenth-century Achill Island history. Initiated in 1834, the Colony provoked intense and often hostile responses over the next half-century, attracting many commentators and travellers to its settlement.

Edward Nangle himself contributed to the Achill artistic tradition, was very interested in tourism and, over the period 1871 to 1879, published a series of Achill Tourist Guides in the Achill Missionary Herald. Nangle’s descendant, Hilary Tulloch, had undertaken much research into drawings and paintings produced by Edward and his children, many during their annual summer stays at Dugort. She has linked woodcuts of the Colony which appeared in the Achill Herald to original Nangle paintings and suggests that Edward provided original drawings to the woodcut engravers.

A feature of the Great Famine legacy is that there are only a small number of contemporary paintings of the period with much of the visual record, relying on illustrated newspapers such as the Illustrated London News.

It was interesting that, in the 2018 Coming Home: Art & The Great Hunger exhibition presented at a number of sites in Ireland in partnership with Ireland’s Great Hunger Museum of Quinnipiac University, USA, the exhibited works and exhibition visuals featured Achill’s Deserted Village and island lazy beds prominently.

One such exhibit was Geraldine O’Reilly’s series of photo etchings of the Deserted Village – a series of over 70 roofless stone cottages on the slopes of Slievemore – while Alanna O’Kelly’s A Kind of Quietism also included a view of Achill lazy beds at the Deserted Village site.

The same exhibition included a painting ‘Cottage, Achill Island’ by Alexander Williams who came to Achill in 1873, built a house there and was the first artist to open up the island to a wide audience. Unlike the later work by Paul Henry, Alexander Williams’ Achill cottage set against the background of Slievemore evokes post-Famine scenes of absence, displacement and deprivation.

Oral History

Perhaps the main contribution of this book lies in its gathering of oral history, stories and personal anecdotes about the Achill artistic community through the decades. An important source for the author was the local historian and former Achill teacher John ‘Twin’ McNamara, who was involved in the revival of Scoil Acla in the 1980s and whose family had links with Paul and Grace Henry, while Anne Burke spoke at the book launch about her family’s friendship with Belgian artist Marie Howet from 1929 until her death.

While the book is richly illustrated with drawings and photographs, there are fewer reproductions of artistic pieces than might be expected, apart from the work of Marie Howet which features prominently.

The book acknowledges the contributions of the current community of Achill artists who live and work on an island where the economic prospects for them and their families are challenging. Several are involved in the organisation of the annual Heinrich Böll Memorial Arts Festival which continues to celebrate the creative arts in Achill, while the Heinrich Böll artist residence at Dugort draws creative people from far and wide to practice their art in Dugort, in the shade of Slievemore.

Summary

Artists have been drawn to Achill Island over the past two centuries, captivated by its splendid Atlantic landscape and ocean light as well as its people. (The author quotes the English writer L.A.G.Strong: ‘I know no place where there is as much light as Achill, where the very stones in the road are alive with light.’)

‘I know no place where there is as much light as Achill, where the very stones in the road are alive with light.’

These artists have held up a mirror not just to Achill Island but to the life of a nation as it transitioned from colonial rule through revolution into independence and the emergence of a new Irish state.

This book contributes to an understanding of the history of the bond between artist and Achill by compiling oral folklore, anecdotes and reminiscences, as well as delving into interpersonal networks through the various generations of Achill artists. In particular, the book further illuminates the unique role of Eva O’Flaherty in animating the artistic and cultural milieu of the island while employing her entrepreneurial skills to improve the material life of a community that has long suffered acute economic hardship.