‘Likely to cause disaffection to His Majesty’, the Seizure of Irish newspapers, September 1919

By Mark Holan

At midday Sept. 20, 1919, as “squally,” unseasonably cold weather raked across Dublin, “armed soldiers wearing trench helmets” joined by “uniformed and plain clothes police” made simultaneous raids on three printing works that published six anti-establishment newspapers.[1]

Their targets:

- Fainne an Lae, the Irish language Gaelic League gazette edited by Colum Murphy, and Nationality, seperatist Sinn Fein’s official organ edited by Arthur Griffith, at Mahons Printing Works, 3 Yarnhall St.

- New Ireland, edited by Patrick John Little, and The Irish World, overseen by Patrick Sarsfield O’Hegarty and Seán Ó Murthuile, at the Wood Printing Works, 13 Fleet St.

- Voice of Labor, a socialist sheet edited by Cathal O’Shannon, and The Republic, a three-month-old paper edited by Darryl Figgis, at Cahill & Co., Ltd., 40 Lower Ormond Quay.

British government authorities in Ireland wielded suppression powers over papers and printing works they deemed were “used in a way prejudicial to the public safety” or potentially bothersome to King George V, as quoted in the headline.[2]

British government authorities in Ireland wielded suppression powers over papers and printing works they deemed were “used in a way prejudicial to the public safety” or potentially bothersome to King George V, as quoted in the headline.[2]

These officials–headquartered at Dublin Castle, a 10-minute walk from all three print works–ordered the seizure of the offending papers and the dismantlement of key parts of the printing presses to stop more copies from being published.

Their power came from the Defense of the Realm Act, sometimes called “Dora.”

Authorized in August 1914 at the start of the Great War, the law was ostensibly aimed at restricting what papers could publish about military activity. Within months, however, the IRB’s Irish Freedom, Griffith’s Sinn Fein and James Connolly’s Irish Worker were suppressed. After the April 1916 Easter Rising “an increasing proportion” of directives from the government censor at Dublin Castle referred “to purely Irish [political] affairs.”[3]

Dozens of Irish newspapers were suppressed during the Irish revolutionary period. Ironically, the Sept. 20 raid fell on the fifth anniversary of John Redmond’s speech to Irish National Volunteers at Woodenbridge, County Wicklow, when had encouraged them to enlist in the British forces during the war.

At the Wood presses on Fleet Street, Little and Ó Murthuile were “forced to remain spectators of the raiding operations, but were refused admission to the works until the military and police had departed.” Three of the firm’s female employees also were prevented from leaving the premises to make their intended bank withdrawal to pay the staff.

At Mahons, “a Sinn Fein flag was hoisted amongst the large crowd which had assembled outside the building” as the soldiers and police departed from the works. At Ormond Quay, “a large crowd collected at the rear of the buildings, but were moved on.”[4]

Before the raids

Since January 1919, when separatist parliament, Dail Eireann began to deliberate at the Mansion House, Dublin Castle had tried to manage the Sinn Fein weeklies and the mainstream press. On April 29, five months after the armistice, the censor reminded editors that Dora remained in effect because

“it is impossible for the Government to permit any section of the Irish Press to be used as an instrument of incitement to organized or other defiance of the law, or for the purpose of inflaming public opinion to a pitch in which acts of lawlessness become possible. There is sufficient reason to fear that [if] there were no effective legal restrictions upon publication, attempts might be made to secure publicity for matter of this description.”[5]

The Castle issued a similar directive on Aug. 28, when it also announced the censor was being discontinued. Irish editors braced for worse. Young Ireland, another of Griffith’s papers, predicted: “The latest move is merely a subterfuge to embark on a wholesale campaign of closing down not only the Sinn Fein papers, but any publication committed to the demand that Ireland be granted the right of self-determination.”[6]

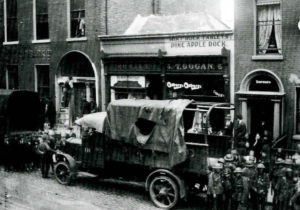

Alongside the suppression of the Dail as an illegal assembly the British seized a series of separatist printing presses

Days later, the Castle outlawed the Dail and declared that a fledgling loan drive to support the separatist government was seditious.

Minister for Finance Michael Collins had asked newspapers to publish notices of the £250,000 loan drive. In part, the content said:

“The proceeds of the Loan will be used for propagating the Irish case all over the world; for establishing in foreign countries Consular Services to promote Irish Trade and Commerce; for developing and encouraging the re-afforestation of the country; for developing and encouraging Irish industrial effort; for establishing a National Civil Service; for establishing Arbitration Courts; for the establishment of a Land Mortgage Bank, with a view to the re-occupancy untenanted lands, and generally for national purposes”.

“It was cleverly worded, and not one of the objects set forth in it were, or could possibly be construed as being in any way illegal from the British angle,” recalled Kevin R. O’Shiel, a Sinn Fein separatist who narrowly missed election in 1918. “Nevertheless, all the papers that published that advertisement were at once suppressed by an Order of the British Military Authorities.”[7]

“It was cleverly worded, and not one of the objects set forth in it were, or could possibly be construed as being in any way illegal from the British angle,” recalled Kevin R. O’Shiel, a Sinn Fein separatist who narrowly missed election in 1918. “Nevertheless, all the papers that published that advertisement were at once suppressed by an Order of the British Military Authorities.”[7]

The Cork Examiner and Evening Echo of the city were suppressed a few days before the six Dublin papers. In an example of the irregular way that Dora was administered, however, authorities lifted the sanctions on the Cork papers even as they raided the republican titles for the same reason.

Press reactions in England & USA

The September raids raised the eyebrows of London editors, including those at The Times, the Westminster Gazette, and the Daily News. “A feeling of uneasiness at the sweeping suppression of newspapers in Ireland is beginning to be manifested in the English press,” reported the Freeman’s Journal, which had not published the loan prospectus but would itself be suppressed by three months later. “

“Since the rigorous action of the British authorities in Ireland under the Defense of the Realm Act, which is still operative in Great Britain, it is now recognized that, whatever the political merits of the case may be, the liberty of the Press, of which Englishmen are so proud, is at stake.”[8]

The British press was uneasy at the suppression of freedom of the press in Ireland, the American papers were openly hostile to it.

Wire service accounts of the suppressions were widely published on the front pages of American newspapers. “Many persons were injured during the raids,” United Press reported[9], though most accounts do not mention any physical confrontations.

News of the suppressed republican papers reached the front page of The Irish Press on Oct. 25. Máire de Buitléir, said to have suggested the name Sinn Fein to her friend Griffith, filed the dispatch from Dublin. Her perspective well-suited the Philadelphia weekly, which had direct ties to the Dail through editor Patrick McCartan:

There are few things about which the average Britisher boasts so loudly as he does regarding the freedom of the press of those living under the glorious British constitution. Doubtless he will not cease to boast while the military and police continue to raid the offices of Irish newspapers, destroy the machinery, break up the type and threaten with pains and penalties the publishers and editors, if they are to resume publication. …

The immediate result of the suppression of the journals printing the prospectus of the national loan was a boom in shares.

People were so indignant of this muzzling of the press that they determined to show what their opinion was by subscribing promptly and generously to the loan. I have heard of dozens of cases in which people have double the amount which they had intended to give, and I know of several touching instances in which poor workingmen and women have put all their savings into the loan.[10]

Afterward

More Irish newspapers were suppressed in October 1919. Near the end of the month, Dublin Castle compiled a list of 43 titles it had acted against since May 1, 1916. Sinn Fein produced its own list for the same period, which contained the names of 51 publications.[11]

Young Ireland and a few other papers sympathetic to the republican cause “carried on a precarious existence in 1919-1921, but the publication through normal channels of books, pamphlets or journals upholding the authority of Dail Eireann or commenting on the news of the day in a spirit openly favourable to Sinn Fein became almost impossible.”[12]

Fainne an Lae resumed publication as Misneach Nov.22, 1919, a month after New Ireland began to publish from Scotland as Old Ireland.[13] Patrick Little recalled:

I went to Glasgow, and … continued there until the 1st February, 1920. It was the Socialist Press, who published my paper for me. … I brought the journal back to Dublin, and, from the 7th February until the 6th March, 1920, I published with Cahill [on Lower Ormond Quay; he was at Wood Printing Works in September 1919]. It was again suppressed … so, I went to Manchester, and published the paper with the National Labour Press, starting on the 13th March, 1920. … In the issue of October 9th, 1920, ‘Old Ireland‘ published the official report of the results of the First Dáil Loan, amounting to £271,849, signed by Michael Collins.[14]

Though outlawed in Ireland the rebel Irish Bulletin was published throughout the War of Indpendence.

In November 1919, The Irish Bulletin became the official publication of Sinn Fein. It contained summaries of the public and secret session of Dail Eireann, its ministries and reports of the Irish Volunteers. The twice-weekly–typewritten, not typeset–was copied off of a Gestetner machine, then bundled into packets and parcels disguised as laundry, groceries, or stuffed into a child’s pram for circulation, mostly outside of Ireland.[15]

As the conflict grew more violent in 1920, the Irish press “became extremely guarded in its news and comments.” Dora was incorporated into the more draconian Restoration of Order Act, August 1920.

In the most troublesome areas, where martial law was imposed, British police and military officers “assumed control of the local press, not only censoring proofs, but compelling the editors to insert matter unfavorable to Sinn Fein” and the republican cause.[16] The Castle also seized foreign papers sympathetic to the Irish cause.

Such efforts, however, had become largely self-defeating. One American correspondent in Ireland observed that among Irish papers suppressed and then allowed to resume publication, “it is the custom to come out in the next issue with a blast against the government which makes the previous ‘libel’ read like a hymn of praise.” [17]

References

[1] “More Papers Suppressed”, Freeman’s Journal, Sept. 22, 1919. Weather from Freeman’s Journal, Sept. 20, 1919.

[2] September 1919 suppression warrant in War Office: Army of Ireland, Administrative and Easter Rising Records, Subseries – Irish Situation, 1914-1922, WO 35/107, The National Archives, Kew. Viewed online.

[3] James Carty, Bibliography of Irish History, 1912-1921, Dublin, 1936, pages xx-xxi. Viewed online.

[4] Description from the Freeman’s Journal, and “Suppression of Six More Papers”, Irish Independent, Sept. 22, 1919.

[5] Carty, Bibliography, page xxiii, quoting the April 29, 1919, directive.

[6] Young Ireland, Sept. 6, 1919, cited by Drisceoil, Donal Ó. “Keeping Disloyalty within Bounds? British Media Control in Ireland, 1914-19.” Irish Historical Studies 38, no. 149 (2012): 52-69.

[7] Bureau of Military History Statement of Kevin R. O’Shiel, WS 1770, p. 861, including loan language.

[8] “English Unease”, Freeman’s Journal, Sept. 23, 1919.

[9] ”Sinn Fein Newspapers Being Suppressed”, The Butte (Montana) Daily Bulletin, Sept. 22, 1919.

[10] “Sinn Fein Convention Meets”, The Irish Press, Oct. 25, 1919. Máire de Buitléir’s dispatch, dated Sept. 30, 1919, is among several stories under the banner headline.

[11] Army of Ireland, Administrative and Easter Rising Records, Subseries – Irish Situation, 1914-1922, WO 35/107, The National Archives, Kew, and The News Letter of the Irish National Bureau, No. 21, Nov. 21, 1919, p. 5., and Dec. 5, 1919, (No. 23), pgs.1-2, 9-10, citing the Sinn Fein lists.

[12] Carty, Bibliography, p. xxiv.

[13] Newspaper publication dates, including The Republic, from Newsplan Project Newspaper Database, National Library of Ireland.

[14] Bureau of Military History Statement of Patrick J. Little, WS 1769, p.47.

[15] Carty, Bibliography, p. xxv.

[16] Carty, Bibliography, p. xxiv.

[17] “British suppression of Irish newspaper raised big storm of protest,” New York Globe, March 20, 24, 1920.

See Mark Holan’s blog series American Reporting of Irish Independence. He can be reached at [email protected]. © 2020 by Mark Holan

Mark Holan © 2020